Immigrant flows, urban renewal, white flight, religious transition, jazz, schisms, CHA failures, demolition by neglect, dithering billionaires, sportswashing, promises made and promises broken—you could write a pretty compelling dissertation about this block of Ashland.

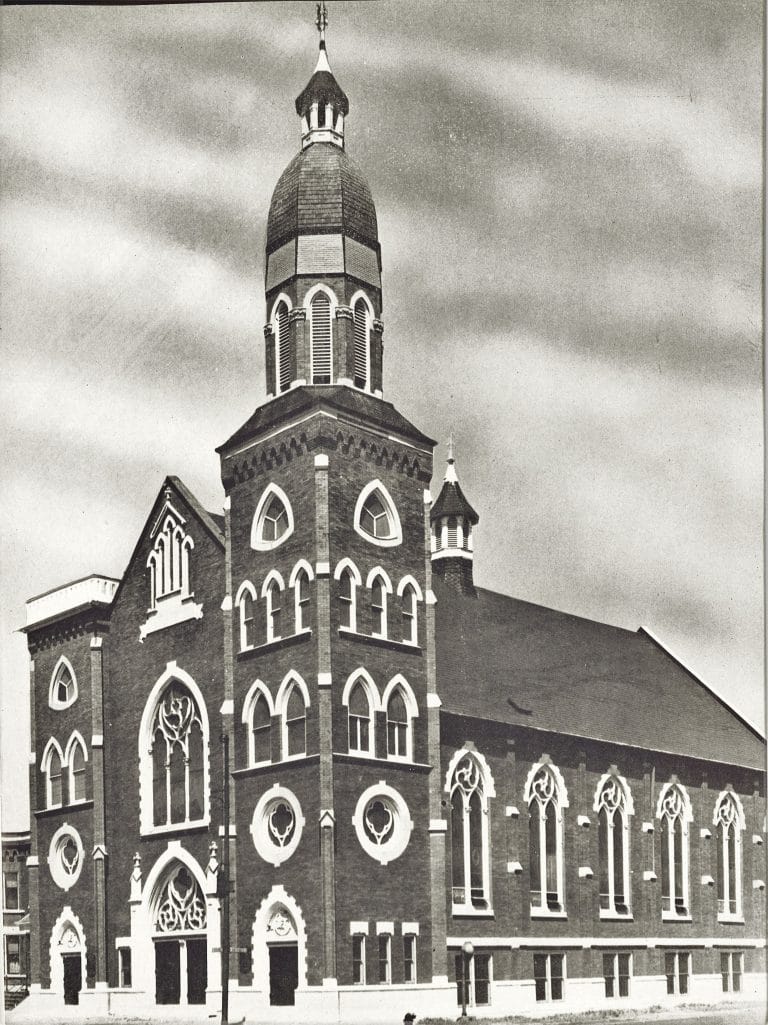

Opened in 1906 and designed by architect Theodore Duesing, Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church was originally a German congregation, but spent the majority of its existence as a Missionary Baptist church–Zion Hill, then St. Stephenson. In between, there were a couple of decades as a Christian Reformed church, part of the Dutch Groninger Hoek community that dominated the near west side from the 1880s-1930s. Bankruptcy, foreclosure, and exposure to the elements trashed what was left of the church in the 2010s, until it was demolished in 2021 by the billionaire Sarowitz family. They intended to replace the (potentially unsalvageable) church with office space for community nonprofits…but nearly four years later the lot is still empty and their company, 4S Bay, has scrubbed the project from its website.

So, what’s changed?

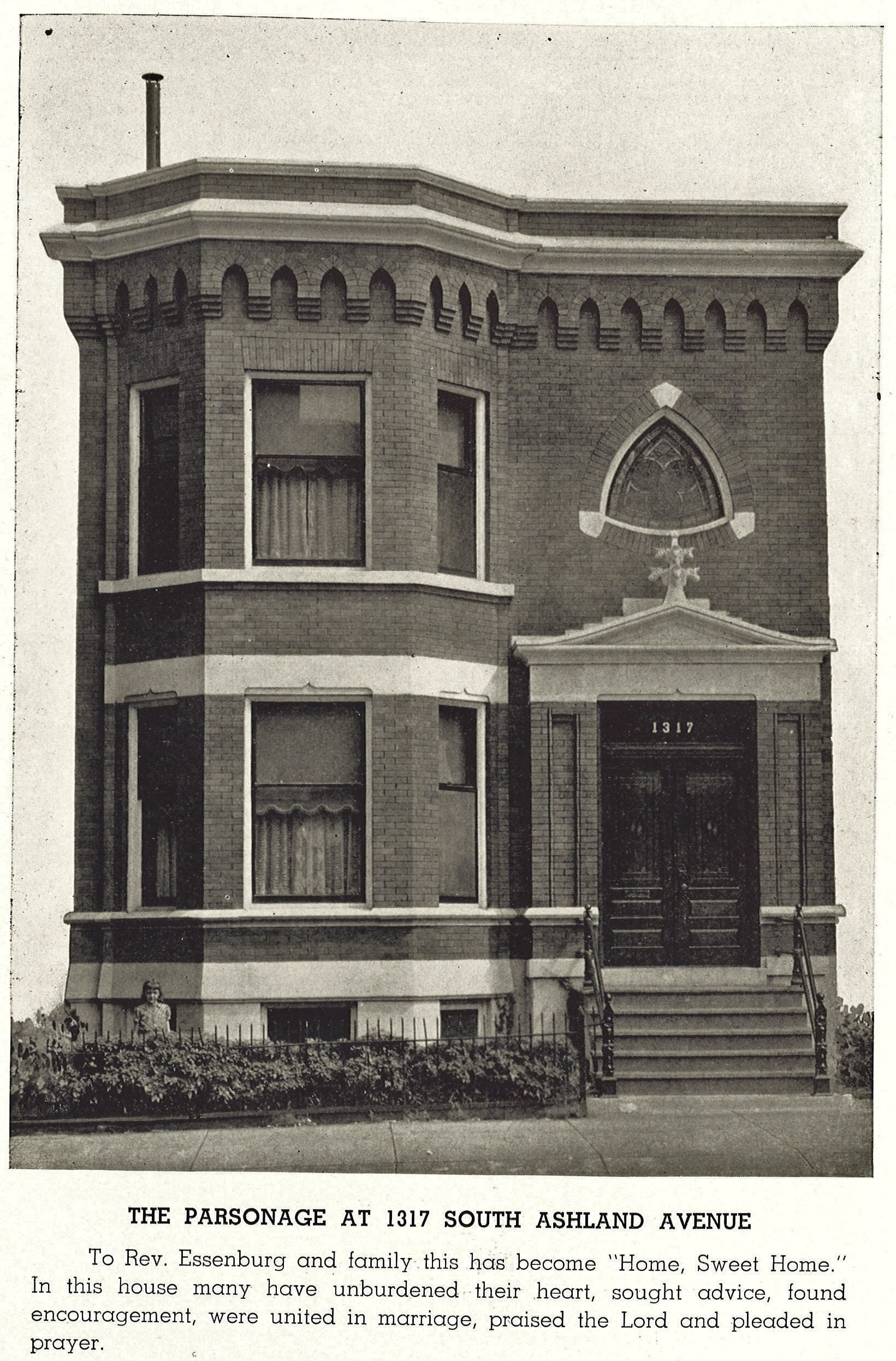

Obviously the church is gone, but the parsonage is somehow not only still standing but completely renovated—although it lost that delightful Reuleaux triangle window over the front door that matched the shape of the church’s windows (...and I guess in general was just made very bland). The dwelling with the stone facade on the left side was demolished in the 1970s, and the absence of the brick building between it and the parsonage–1315 S. Ashland–means this postcard was published before 1909, when that building was built. The three story building to the right of the church–with the sign reading “BITTER WINE” on top–was the Joseph Triner Company factory, which made medicinal liquors. That building came down between 1995 and 2009. Ashland Avenue is also quite a bit wider nowadays, after the city dramatically widened the street in the 1920s.

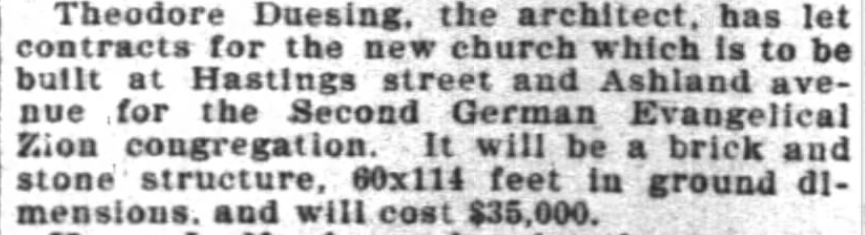

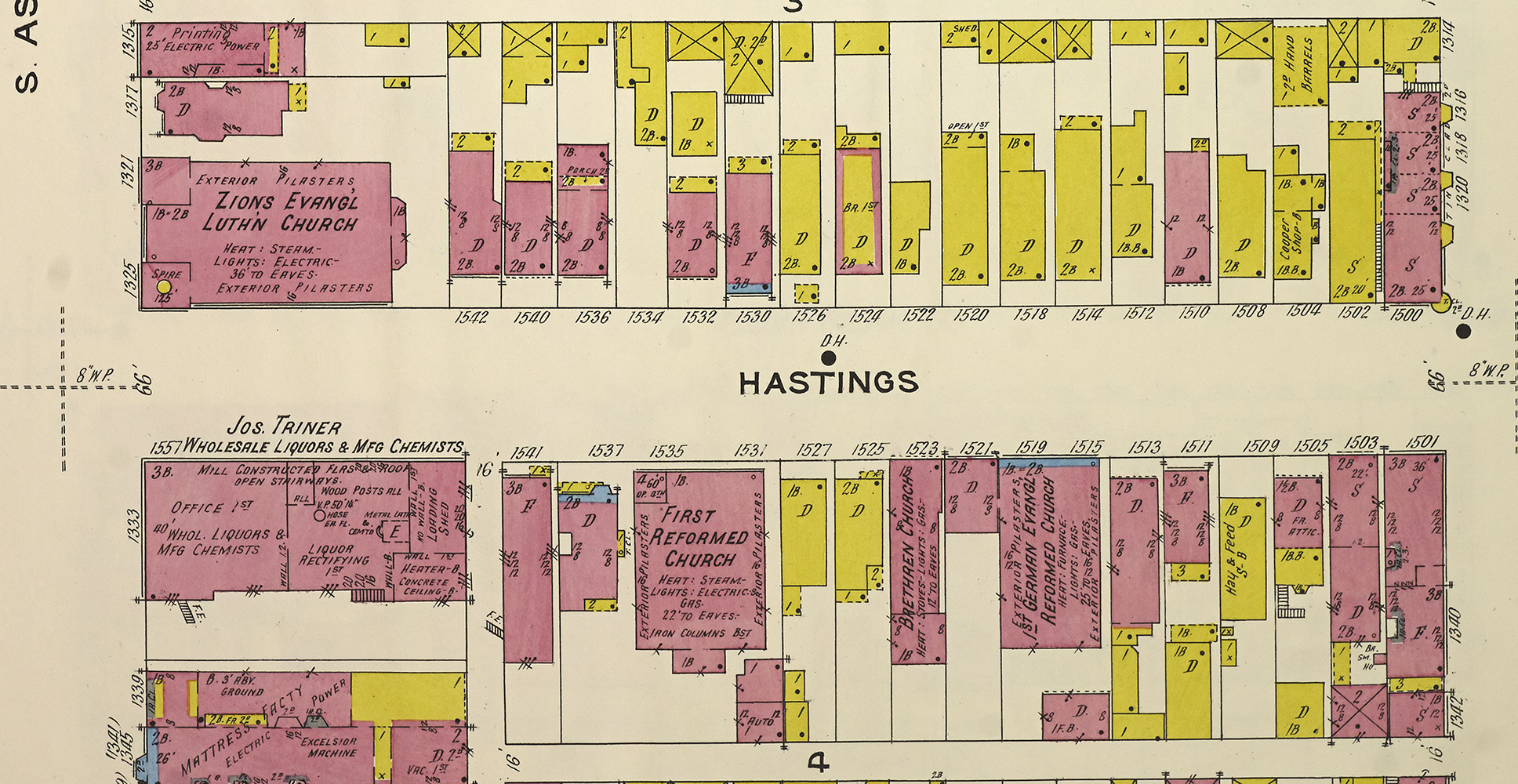

Chicago grew so fast at the turn of the century that ethnic communities—and their places of worship—bounced around at speed. Here, it started with the Germans–selling their old building to a Jewish congregation, the Zion German Evangelical Lutheran Church hired architect Theodore Duesing to build them a new church on the corner of Hastings and Ashland in 1905. This must have been one of the holier blocks in the city–in 1917 there were four churches on this single block of Hastings (Zion Evangelical Lutheran, First Reformed, the Brethren Dunkard, and German Evangelical Reformed).

1906 article about the dedication in Abendposten, the Internet Archive | Undated photo | 1905, Duesing lets the construction contracts | 1917 Sanborn Map

Duesing was an immigrant from Germany himself and popular within the community. Dedicated in 1906, Zion Evangelical Lutheran came at the beginning of the most productive period in Duesing’s career, and he spent the next decade busy designing homes, apartment buildings, commercial buildings, and at least one other (originally) German church (what is now St. Stephen King of Hungary on Augusta).

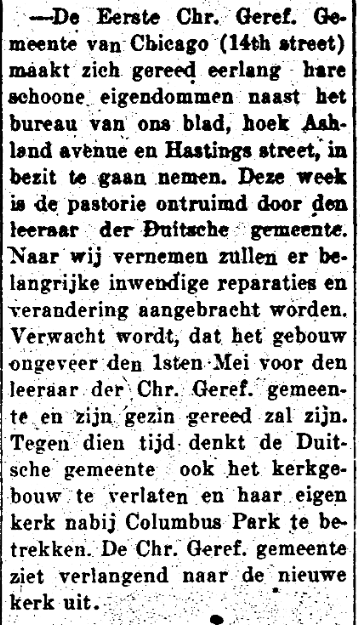

A Dutch community, the Groninger Hoek, sprouted on the lower west side and in 1923 the Germans sold the building to the First Christian Reformed Church, one of the religious pillars of the Chicago Dutch. This stretch of Ashland Ave was the heart of the Groninger Hoek–in addition to the First Christian Reformed Church, the offices of Chicago’s Dutch-language newspaper, Onze Toekomst, were located in the (extant) building next to the church’s parsonage (1315 S. Ashland).

1923 Dutch-language article in Onze Toekomst about the First Christian Reformed church moving in next door | 2024 photo of the former Onze Toekomst building, now how to Greater St. Stephenson MB, and the former parsonage | undated photo of the parsonage

The West Side Dutch leveraged the area’s proximity to industry and the Loop to monopolize Chicago’s garbage collection industry. More than 350 independent garbage companies called this neighborhood home. While we don’t necessarily associate the Dutch with garbage collecting anymore, you can still spot the legacy of the Groninger Hoek’s carting businesses today. Waste Management, the largest garbage collector in the US, traces its roots back to a company Harm Huizenga founded in the neighborhood. Today, the billionaire Huizenga family has turned that wealth into a seat in the US House and enormous handouts from Republican presidents.

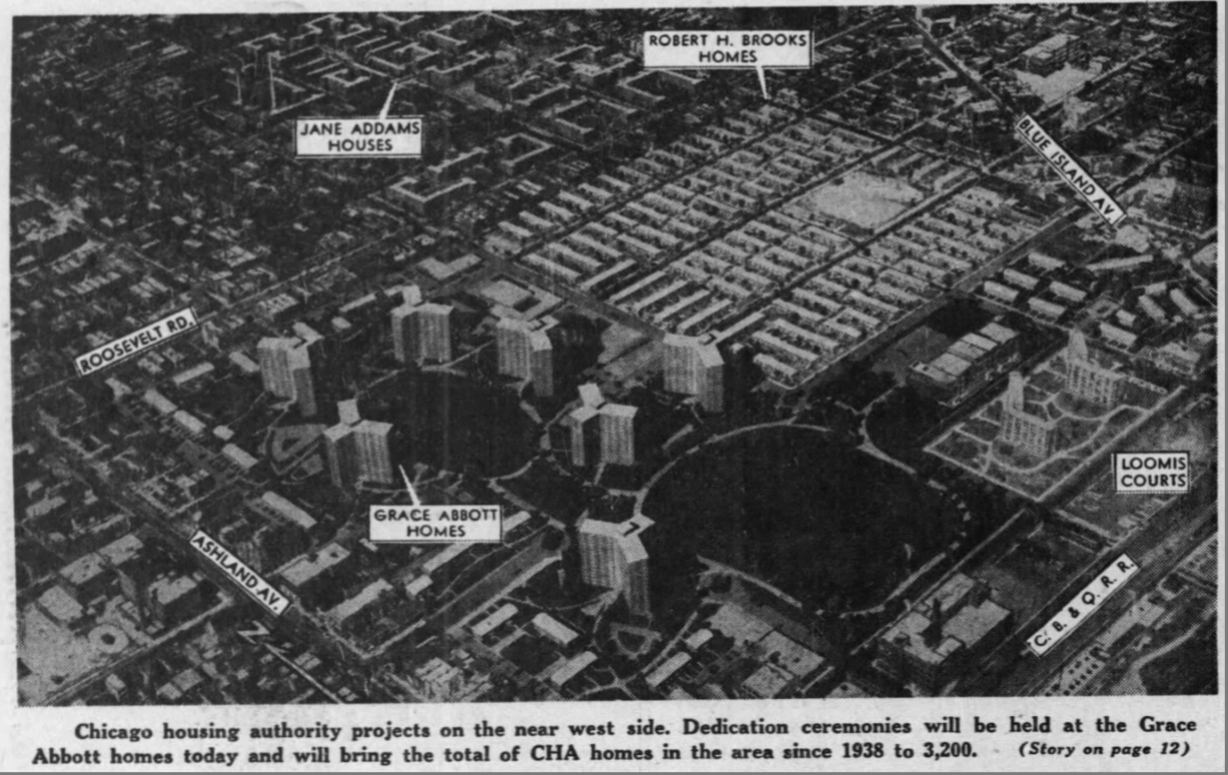

The West Side Dutch were white flight innovators. Particularly after the Chicago Housing Authority built their Jane Addams Homes development nearby in 1938, the Dutch took their capital west down Roosevelt and ringfenced it in suburbs like Berwyn and Oak Park. The First Christian Reformed Church followed their congregants, selling the church to Zion Hill Missionary Baptist Church in 1944 and moving to Cicero.

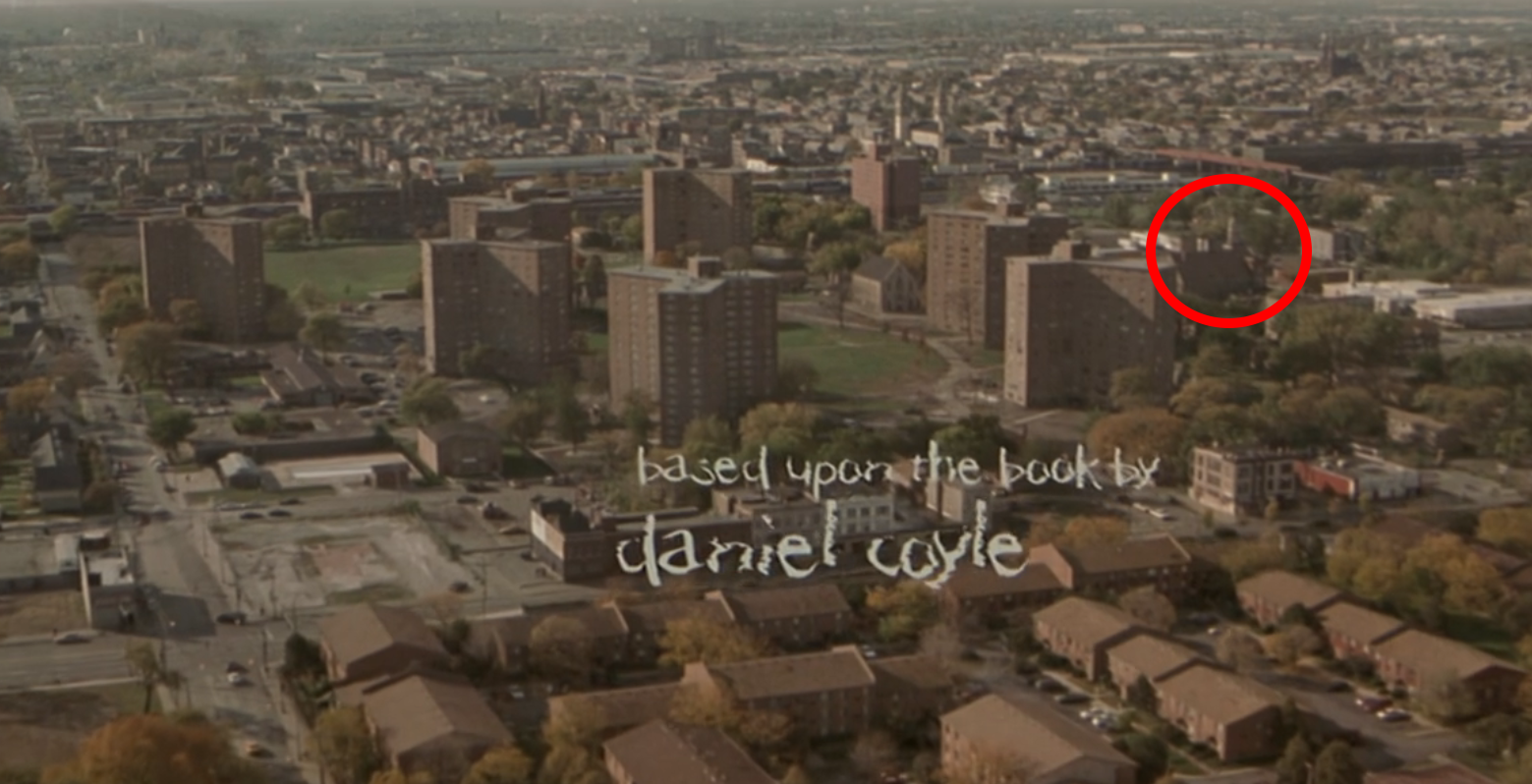

The neighborhood was already in the midst of demographic transition when Zion Hill—a Black congregation—moved in, and large-scale urban renewal soon followed, as the Chicago Housing Authority’s high-rise Grace Abbott Homes rose next door. One of the A’s in the CHA’s ABLA Homes (Jane Addams Homes, Robert Brooks Homes, Loomis Courts, and Grace Abbott Homes), more than 17,000 people moved into ABLA between the late 1930s and the early 1960s.

The nearby Jane Addams Homes were arguably the best hope for an integrated CHA development, because, unlike the Lathrop Homes or Trumball Park Homes (where white people rioted when CHA accidentally moved a Black family in in 1953), this neighborhood was relatively diverse by Chicago standards, with a small Black community already established. Instead, the CHA didn’t even try to integrate, and 97% of units at the Jane Addams Homes were initially reserved for white families. Within 15-20 years those racist quotas had fallen apart anyway—by the 1950s white people refused to live in the area.

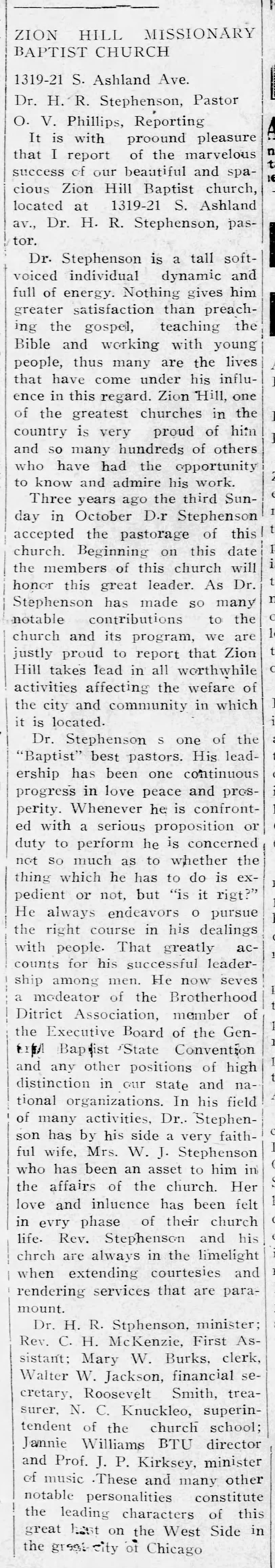

1955 photo from an article about the opening of the Grace Abbott Homes | undated photo of the Grace Abbott Homes, UIC Library via Chicago Collections | Screenshot from Hardball (2001) | 1949 article on Zion Hill M.B.

Under the leadership of Rev. Henry Rutherford Stephenson, Zion Hill M.B. worshipped here pretty uneventfully for more than 25 years. Perhaps most notably, in the 1950s jazz legend Ramsey Lewis had his first job out of high school here, accompanying the choir here as an organist (his father served as Zion Hill’s choir director).

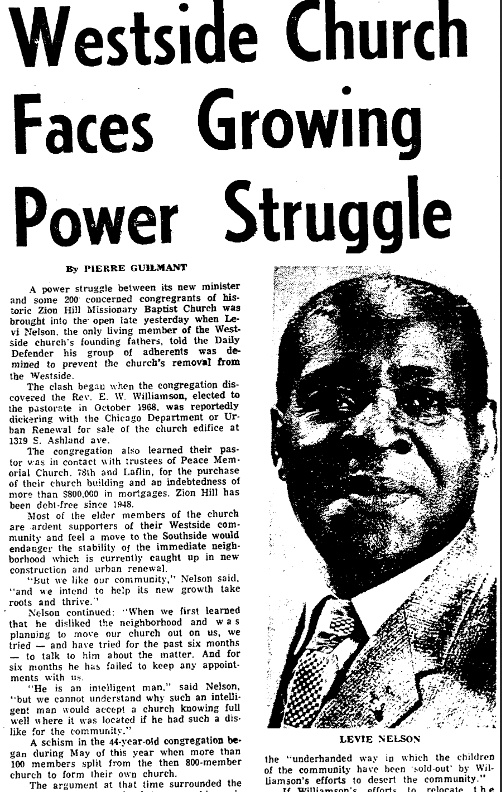

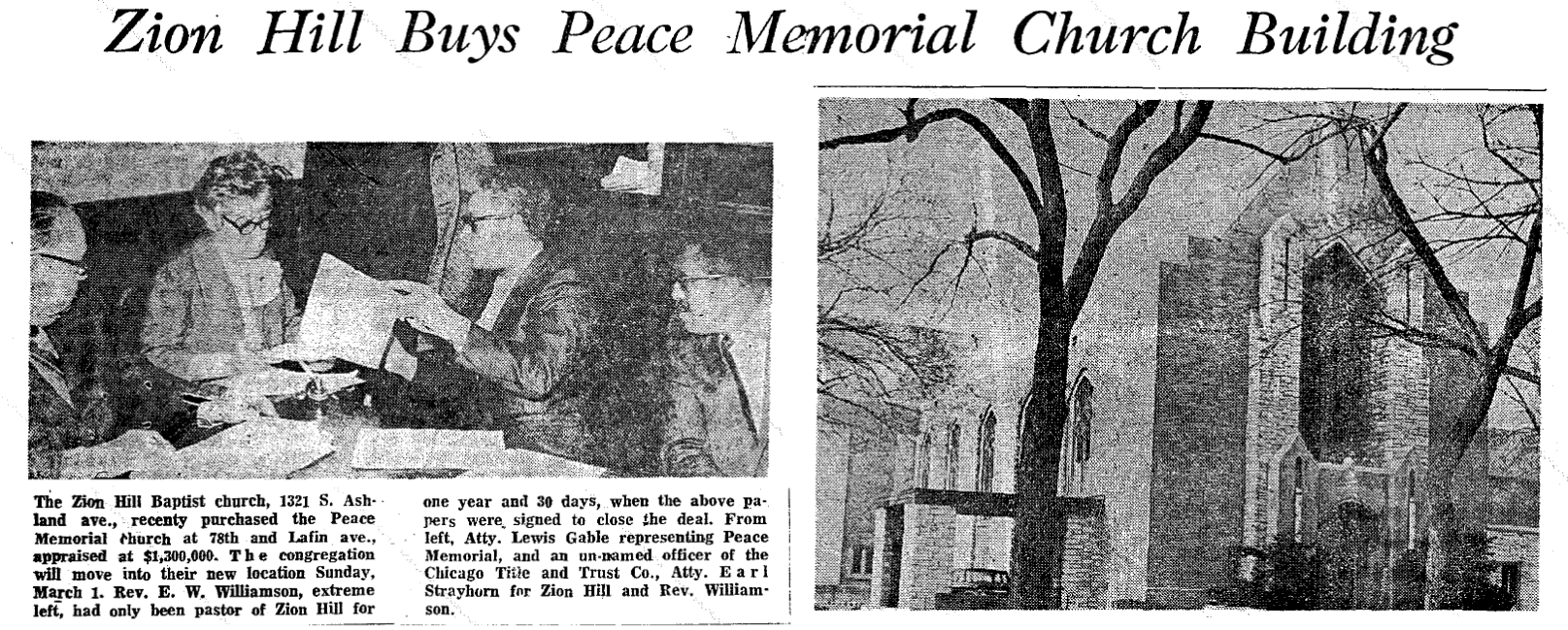

After Rev. Stephenson’s death in 1968, Zion Hill’s connection to the Near West Side began to fray when Reverend E.W. Williamson was elected to the pastorate. Williamson moved to Chicago from Memphis for the position, and while he had the option to live at the parsonage next door (with the delightful matching Reuleaux triangle window), Williamson said the “surroundings are not decent enough to raise my family”. Instead, Rev. Williamson attempted to move the church to the South Side, and Zion Hill bought a building in Auburn-Gresham.

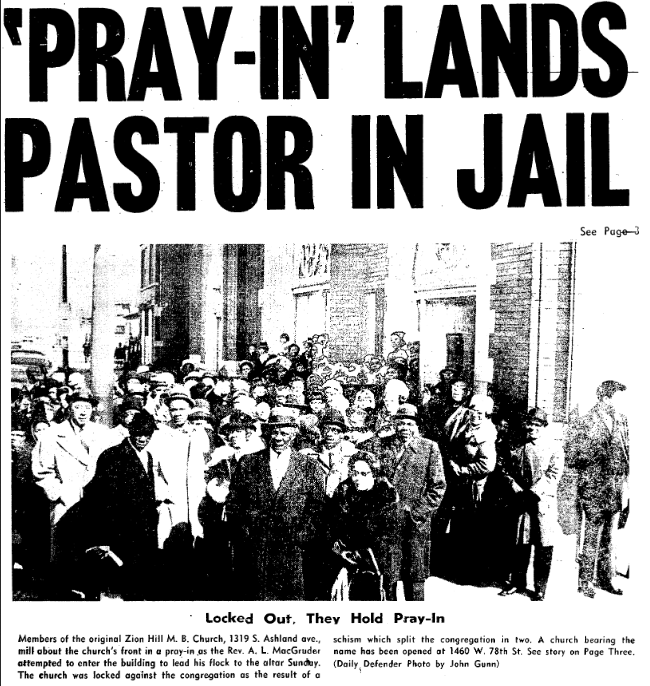

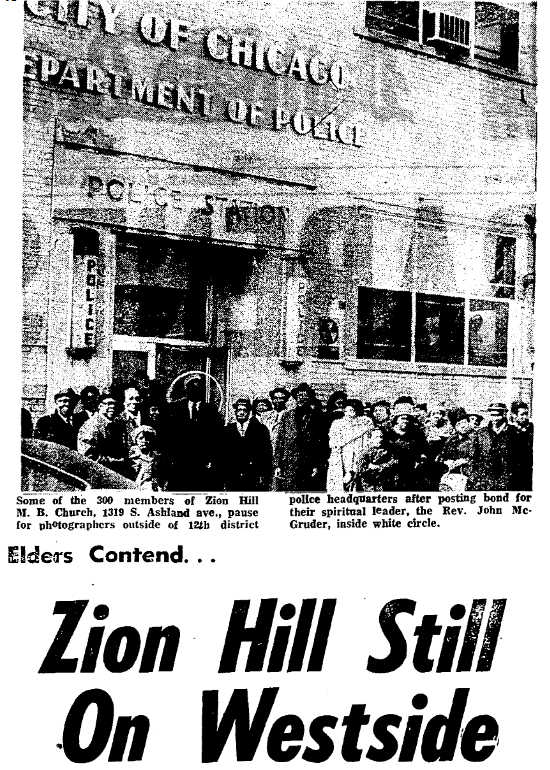

1969-1970 articles about the power struggle over the future of Zion Hill in the Chicago Defender, the Chicago Tribune, and the West Side Torch

Rev. Williamson’s move caused a massive split in the congregation—more than 300 members protested the move. Rev. Williamson locked congregants out of the church on Ashland, and a pastor ended up in jail after he broke into the locked church with a crowbar, holding a pray-in to protest the move.

The group that moved kept the Zion Hill M.B. name, and they’re still worshipping in the building that Rev. Williamson bought on 78th St. & Laflin in Auburn-Gresham. Although they lost the name, I believe the group that wanted to stay kept the building, as it became St. Stephenson Missionary Baptist Church (probably named for Rev. Stephenson?).

1970s photos, Illinois State Historic Preservation Office

The Grace Abbott Homes next door were torn down in the mid-2000s during the CHA Plan for Transformation, in which the agency razed most of Chicago’s public housing developments with the promise that they’d replace them with 25,000 new or rehabbed units. More than 20 years later, the CHA still hasn’t delivered all the units they promised. Even worse, they actually leased out the old Grace Abbott Home land to the Chicago Fire to build their new practice facility (thus that “astroturf deliveries” sign in the orange spray paint).

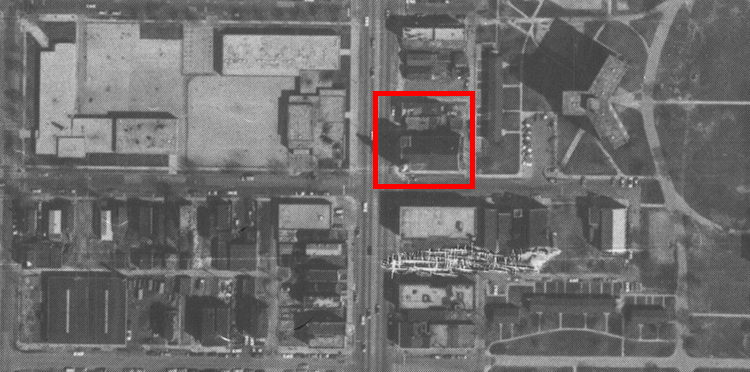

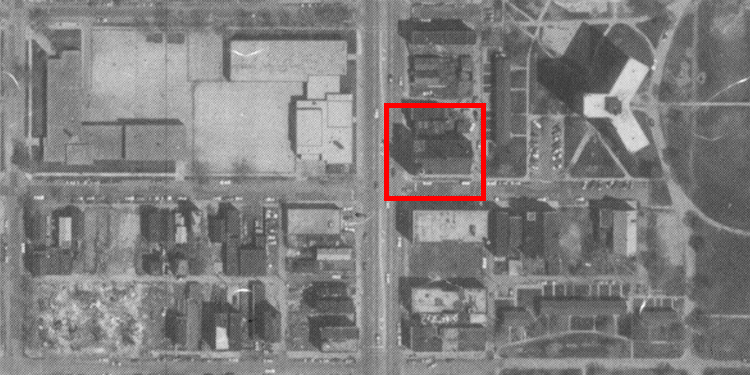

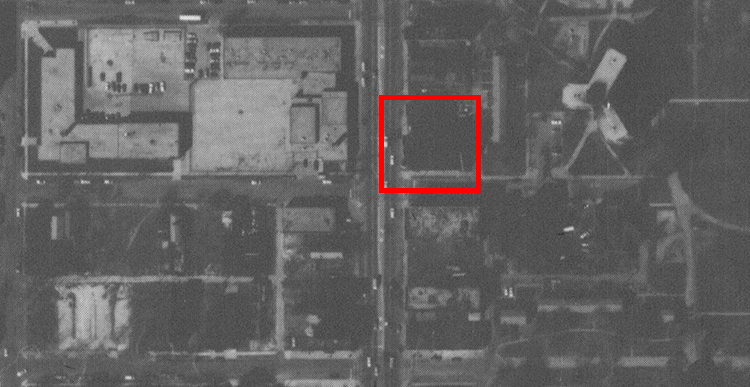

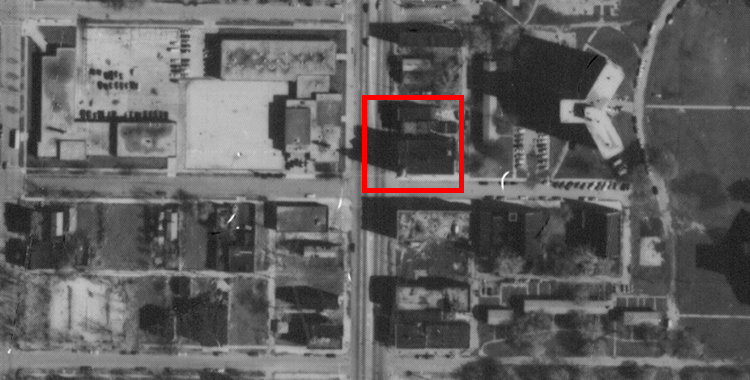

Aerials from 1938-1995, Illinois State Geological Survey and Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning

With the neighborhood depopulated after the razing of the ABLA homes, it looks like St. Stephenson struggled to maintain the massive old church in the 2000s and 2010s. There was a bankruptcy, foreclosure proceedings, and the church lost its cupola in 2014. Open to the elements for years, the decaying church became a popular urban exploration location.

4S Bay Partners—the family office of Paylocity billionaires Jessica and Steve Sarowitz—bought the site in 2019 for $900k, and Greater St. Stephenson moved into the cozier, more manageable storefront at 1315 S. Ashland. After a 90-day demolition delay—required because of the church’s orange rating on the Chicago Historic Resources Survey—the building was razed in winter 2021. 4S Bay Partners planned to replace the church with a six-story office and retail building, focused on providing space for community organizations. The company received a foundation permit in 2023, but there’s a conspicuous lack of action two years later and 4S Bay has removed the project from their website–looks like this might sit as a vacant lot for a while.

Production Files

Further reading:

The block of Hastings between Ashland and Laflin in three fire insurance maps, 1893, 1917, and 1950.

Aerials of the four block area bounded by 13th, Laflin, 14th, and Paulina.

1938, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995

This is the spot I took the photo from.

Member discussion: