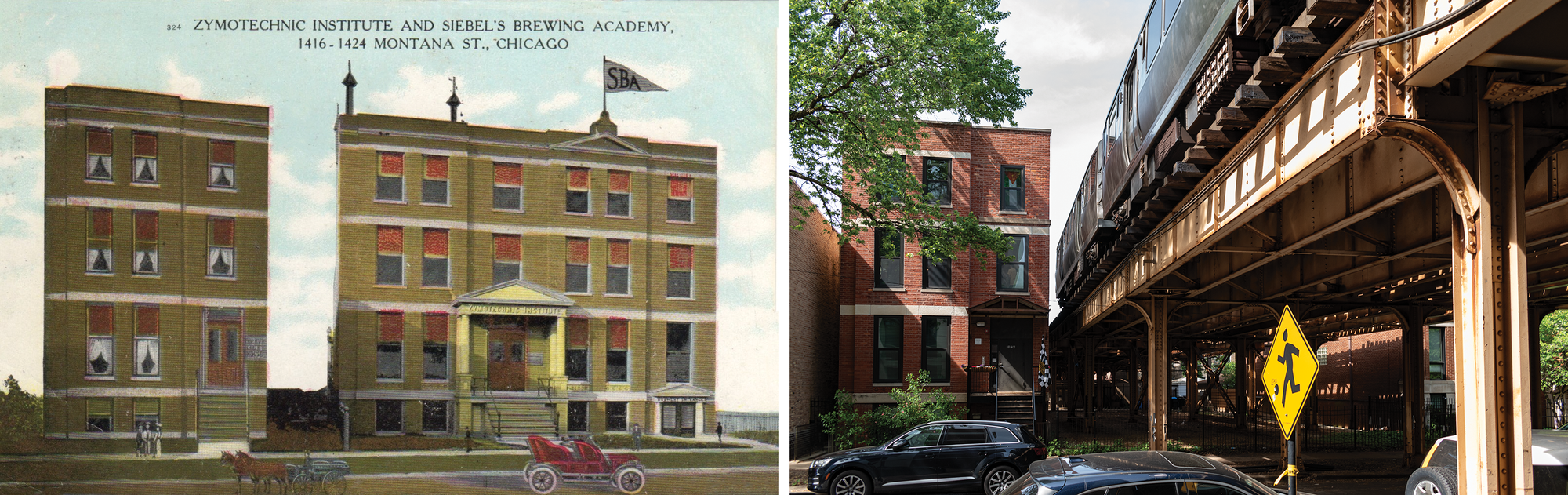

Postcards as an unreliable depiction of an idealized past, an old-timey archaic science, and a plucky Chicago survivor that’s housed a wild variety of tenants–this is a fun one.

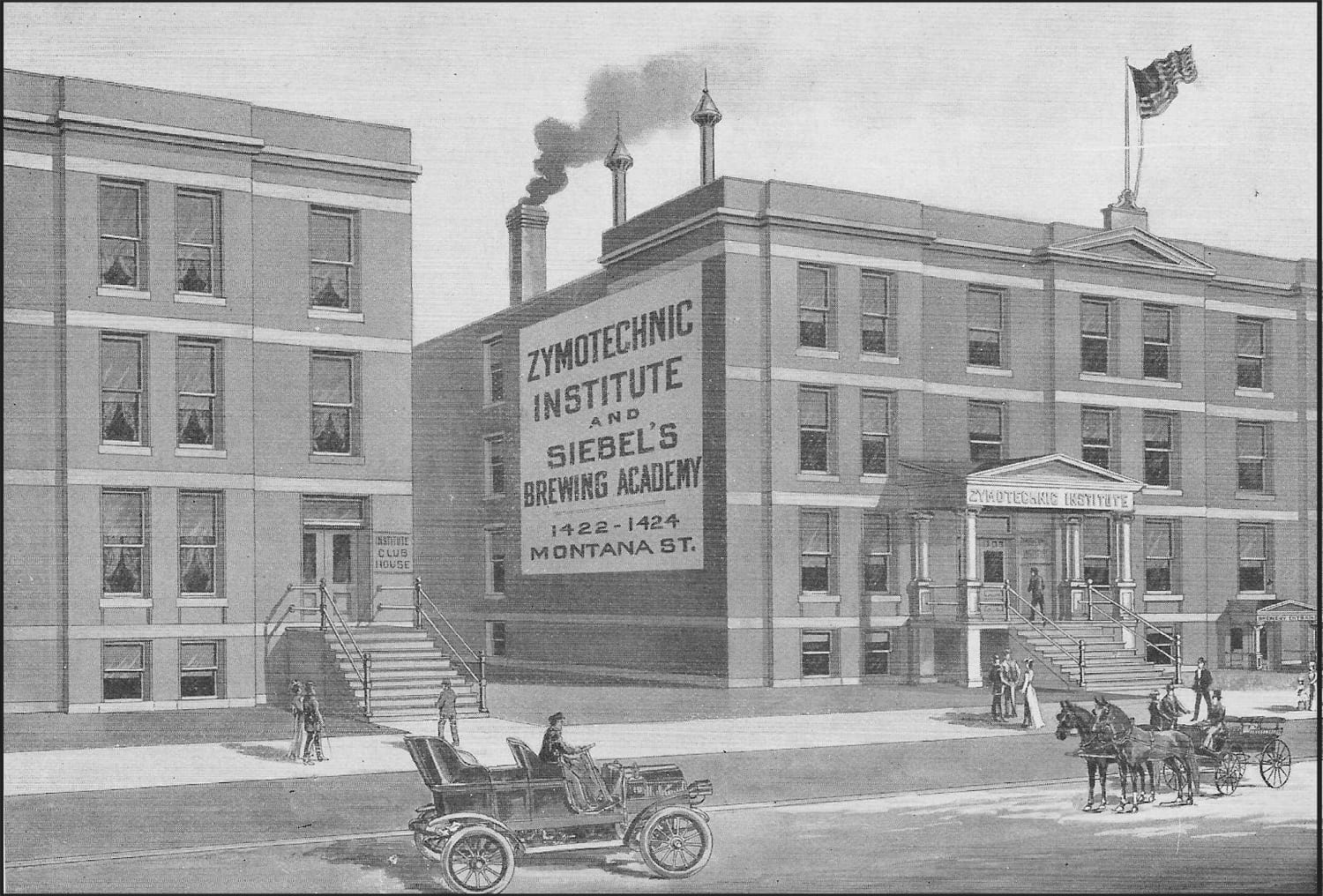

The plucky survivor–970 W. Montana, once the Siebel Institute’s clubhouse–is an example of how freewheeling adaptive reuse can be: built as a dwelling, used as a social space, converted into light manufacturing, rehabbed into loft offices, and now the upper floors recently turned back into housing. One noteworthy tenant over those nearly 140 years was the Windy City Times, Chicago’s pioneering LGBT newspaper. The old-timey science here is zymotechnics, the applied science and technology of fermentation. Still in operation in the West Loop, the Siebel Institute of Technology is the oldest brewing school in the Americas, but when it opened it aspired to even more. Zymotechnics combined aspects of chemistry, microbiology, engineering, and tech. That meant brewing and malting, sure, but also refrigeration, bottling, engineering, and baking. The postcard misleads with the missing steel trestle of the Chicago L–the Northwestern Elevated Railroad constructed this track section (which today carries the CTA Brown and Red lines) in 1896, well before the Siebels moved their family business here.

So, what’s changed? A slightly silly question to ask, since the postcard depicts a perspective that didn’t actually exist, with the elevated tracks edited out in the postcard publishing process. That said, 970 (the building on the left) looks basically the same. The lintel on the rightmost section of the third floor disappeared and what looks like a bit of reinforcement has been added below that window. It also received a metal awning sometime in the last 15 years. To the east, past the L tracks, the main Siebel Institute buildings were demolished in the 1960s, replaced with single-family homes as gentrification skyrocketed in Lincoln Park in the 1980s.

When it was built in the late 1870s or early 1880s, 970 W. Montana was the westernmost of six identical dwellings that ran from 958 W. Montana to 970. It’s worth remembering that, for all the complaints about cookie-cutter modern architecture, 19th century real estate development was also incredibly repetitive–now it just benefits from the patina of time. For context, 960 W. Montana–a 10-room house and one of the buildings later turned into the Siebel Institute–rented for $30 a month in 1894, the equivalent of roughly $1,100 today.

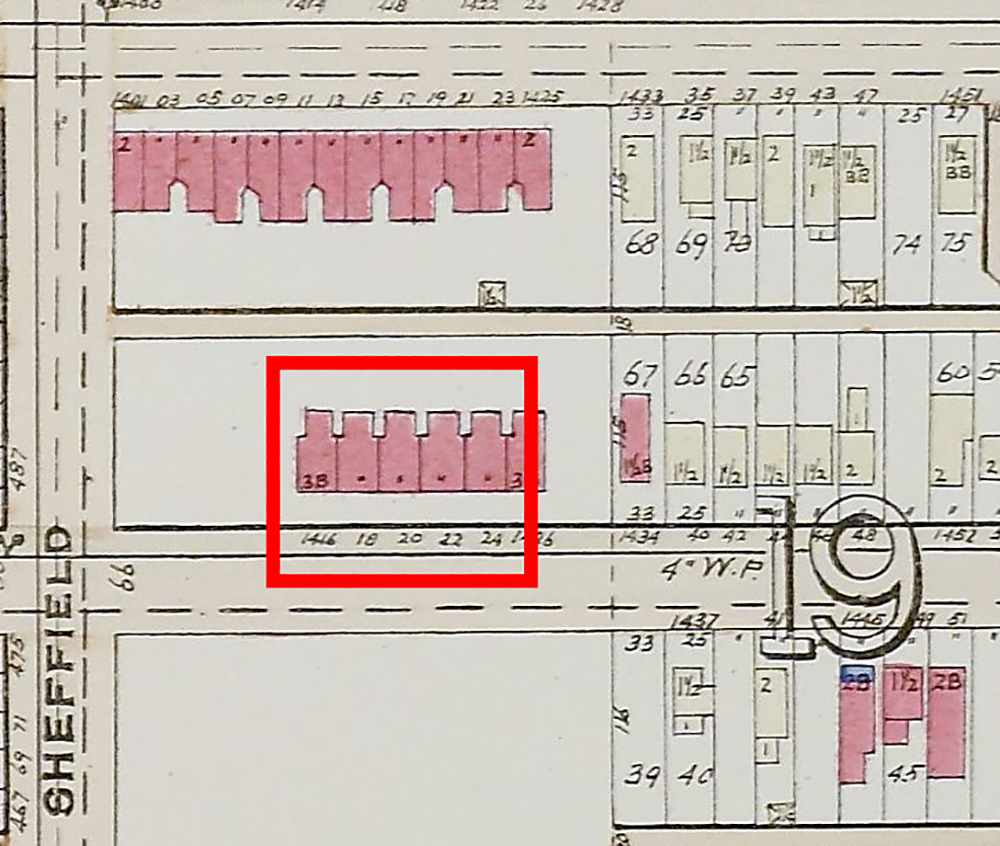

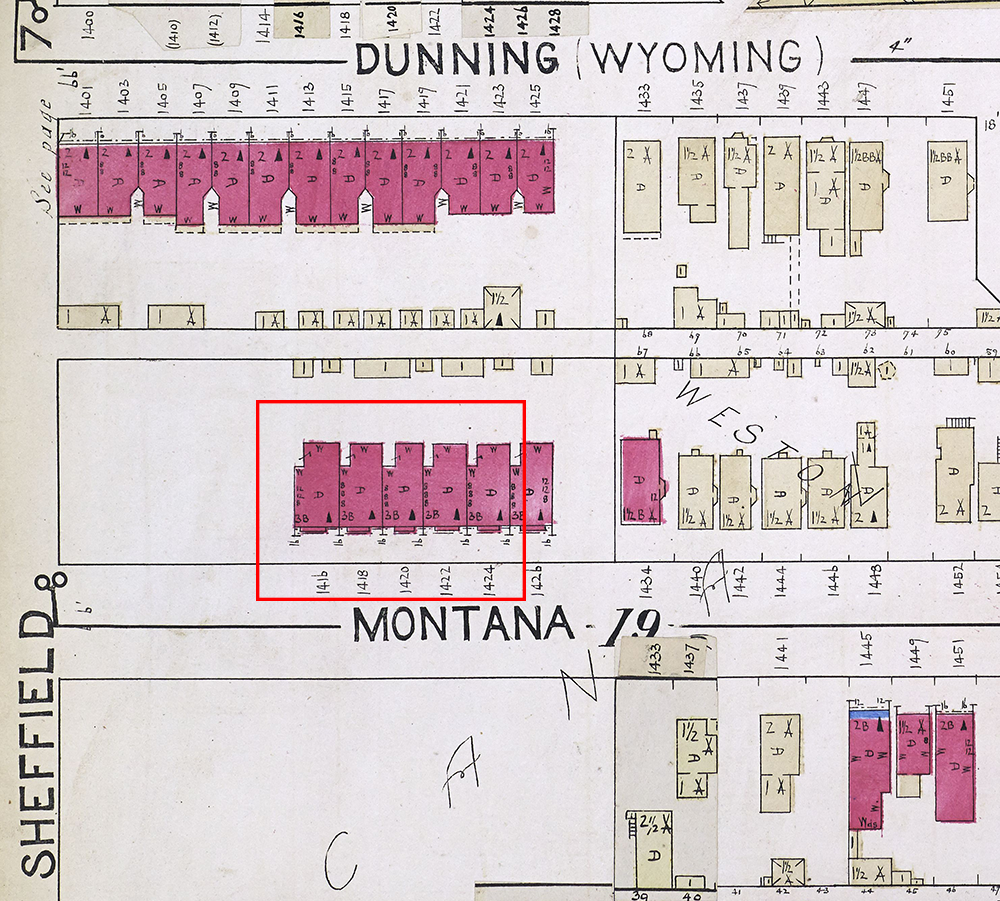

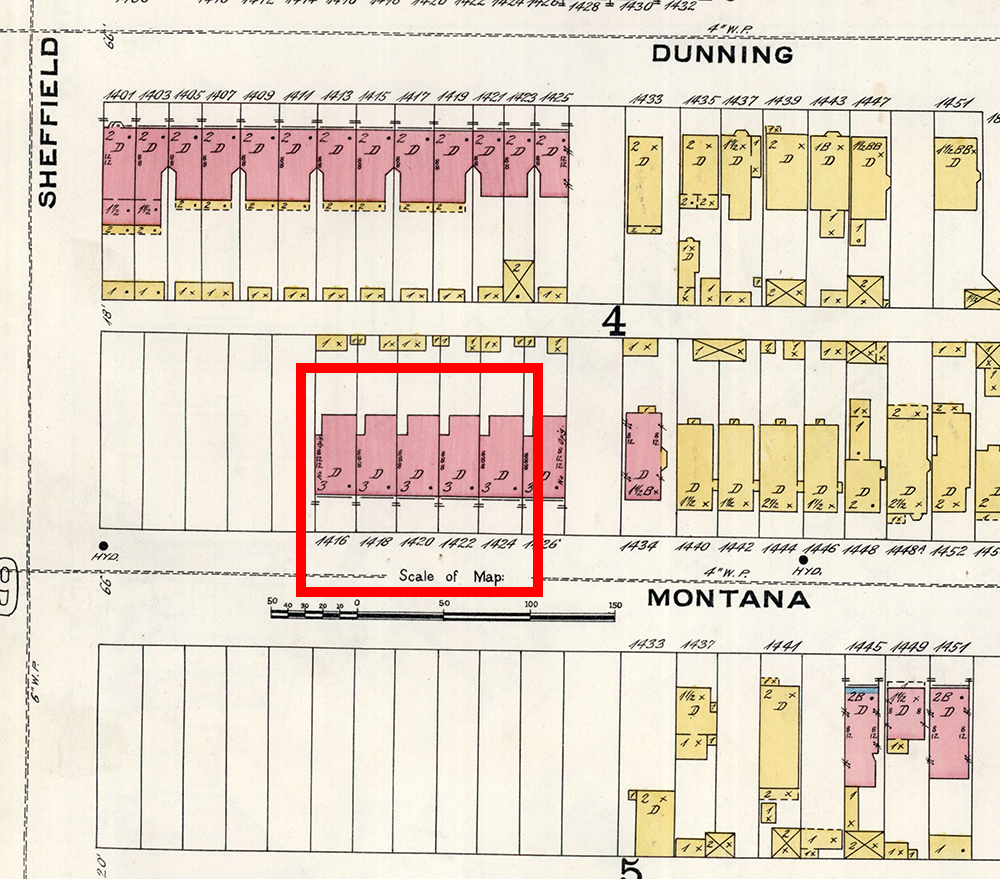

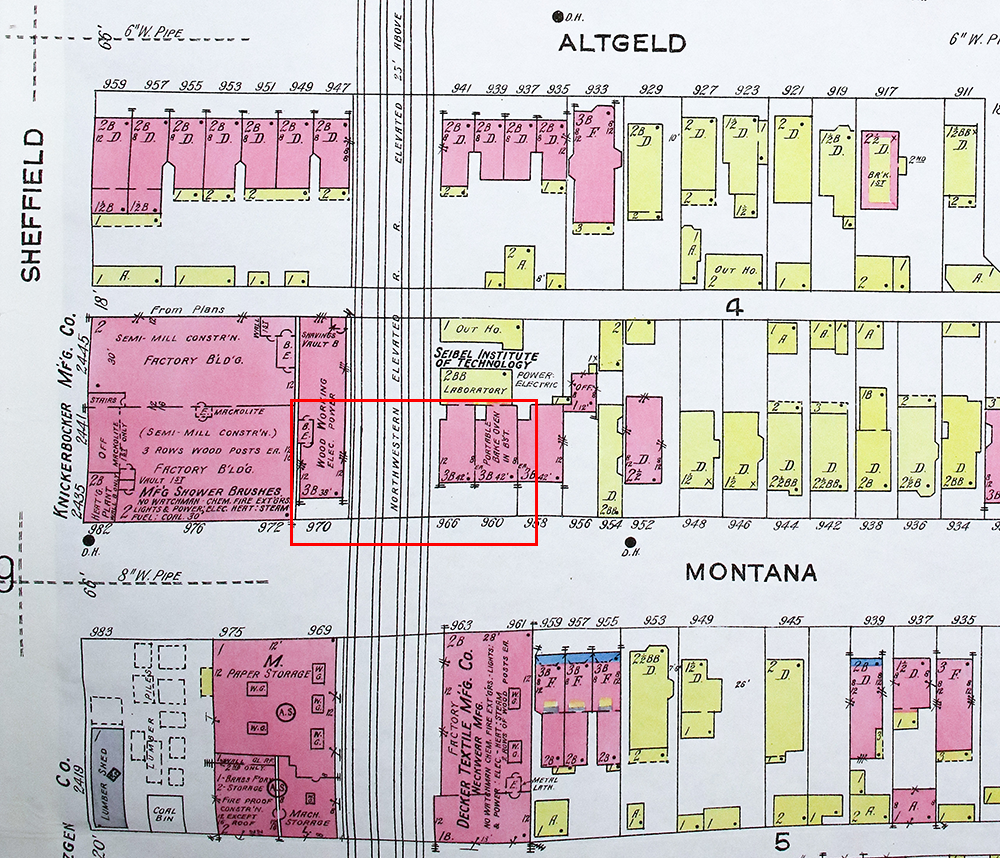

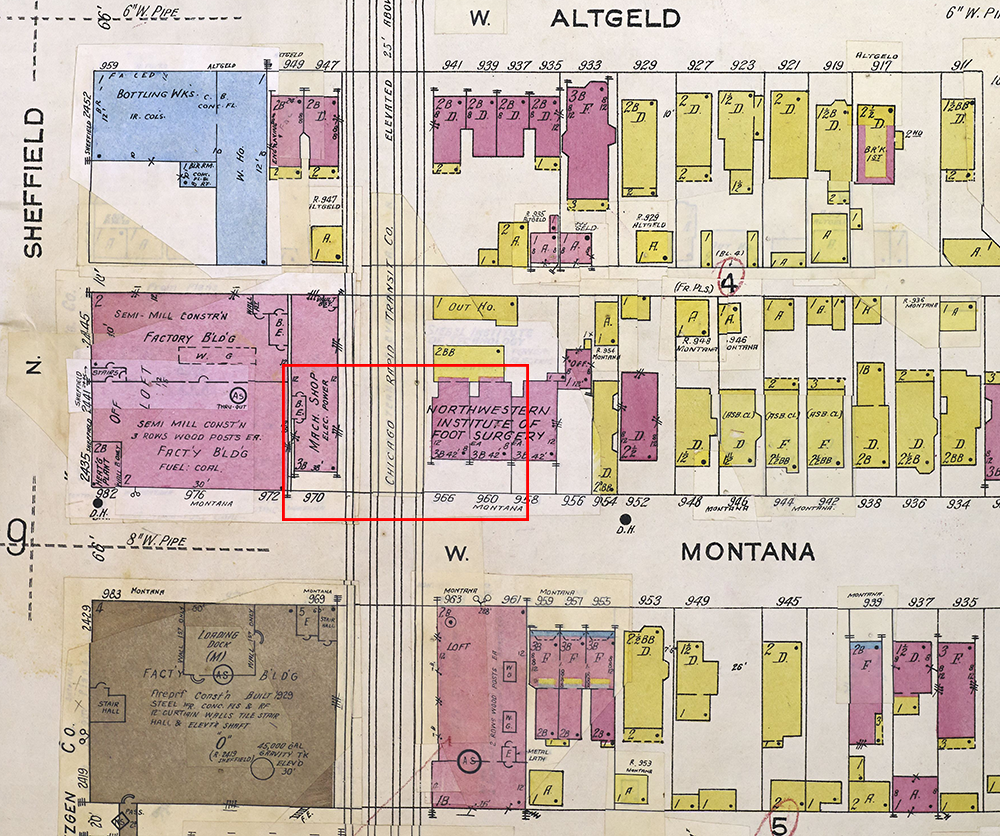

1887 fire insurance map | 1891 fire insurance map | 1894 fire insurance map

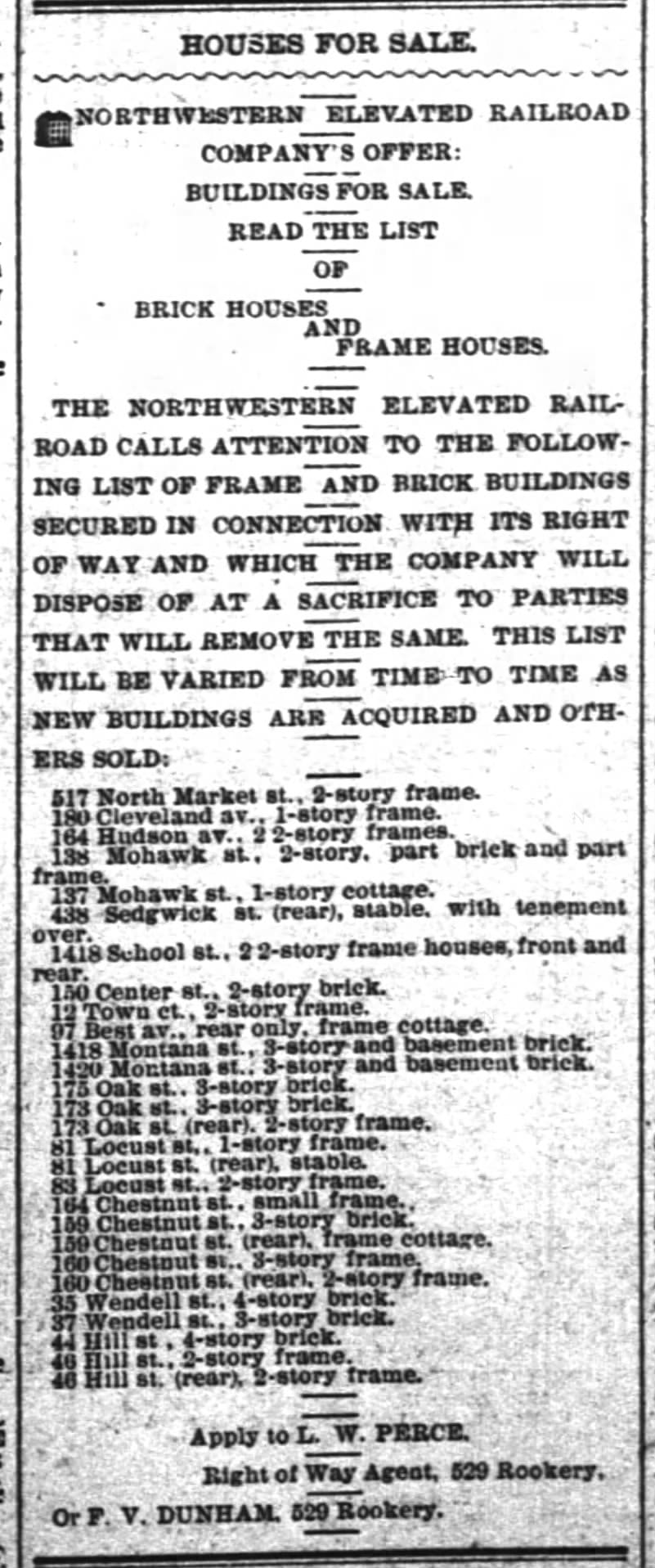

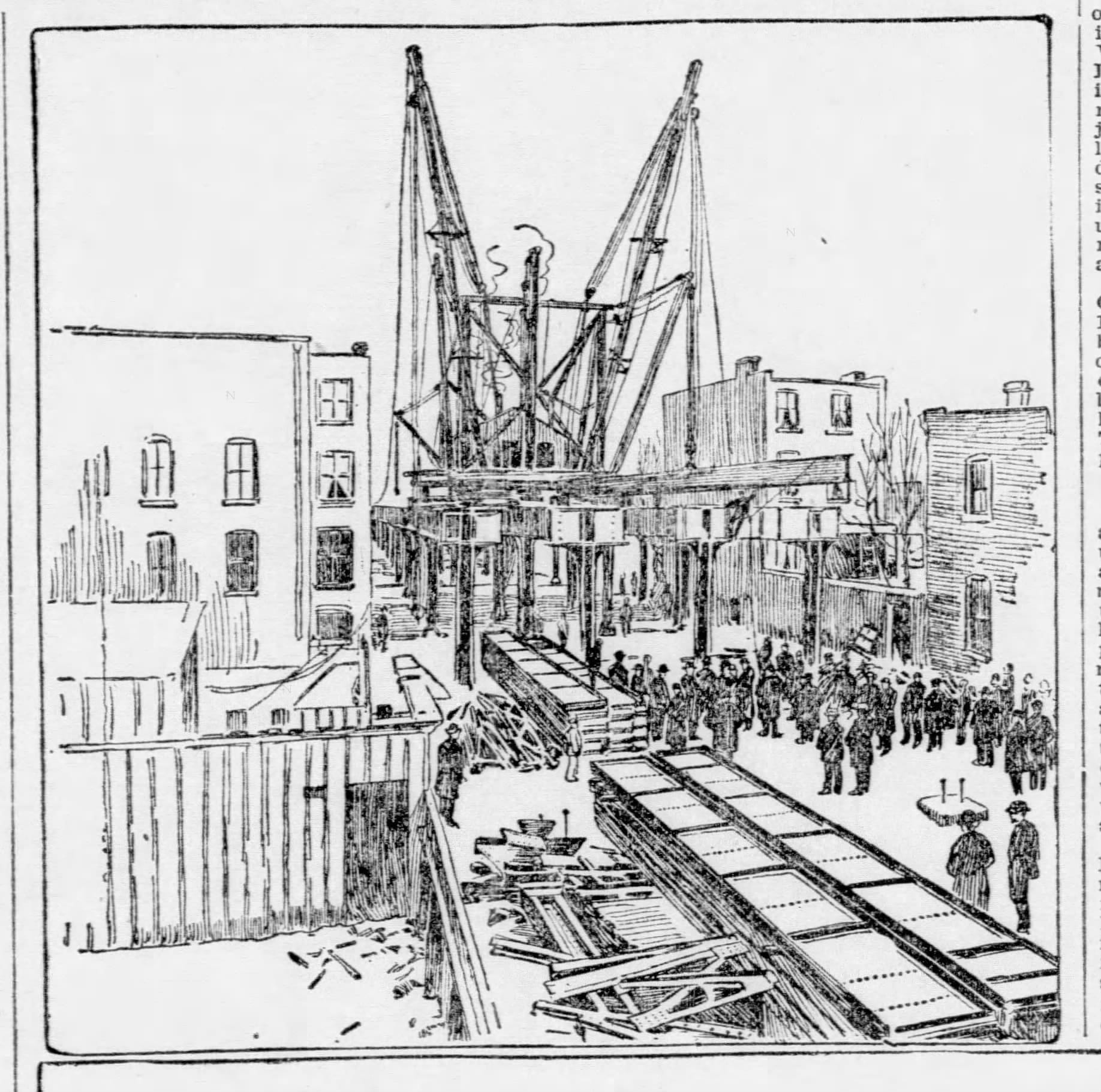

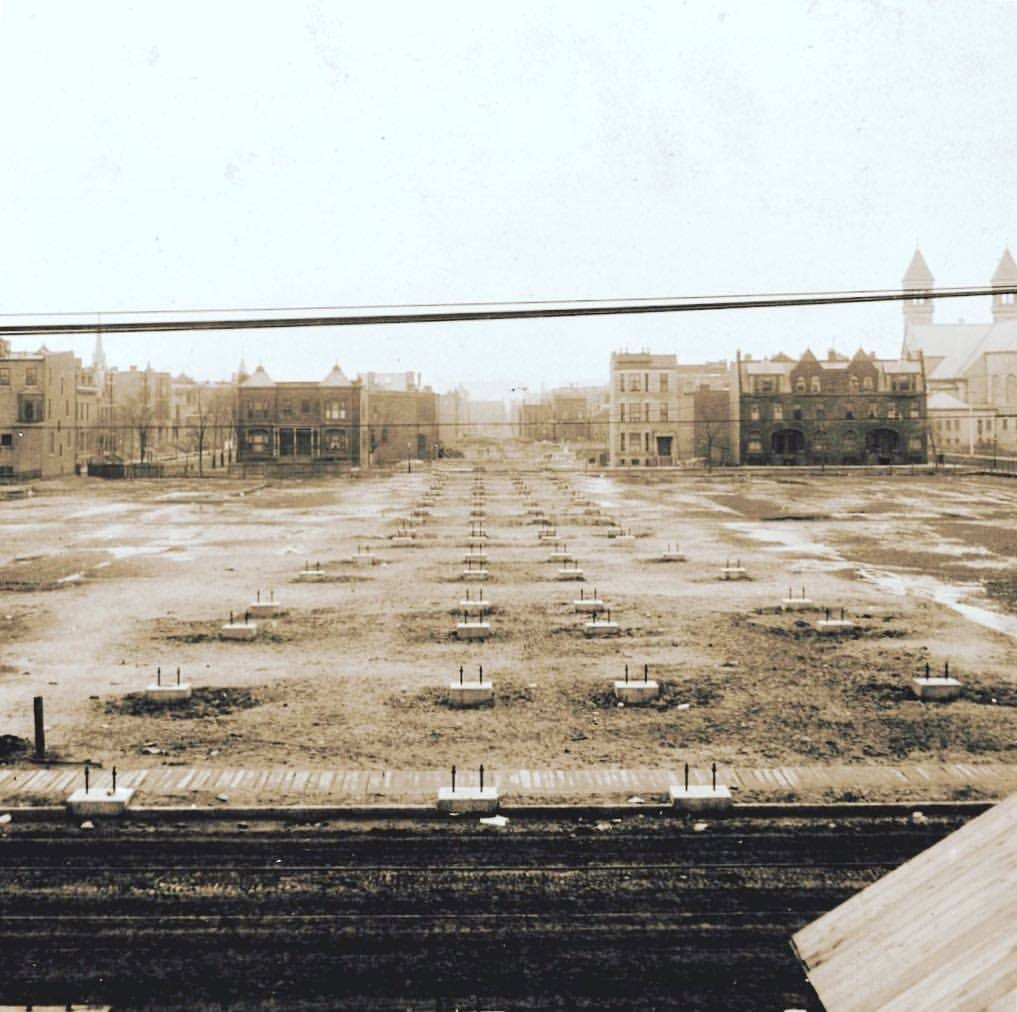

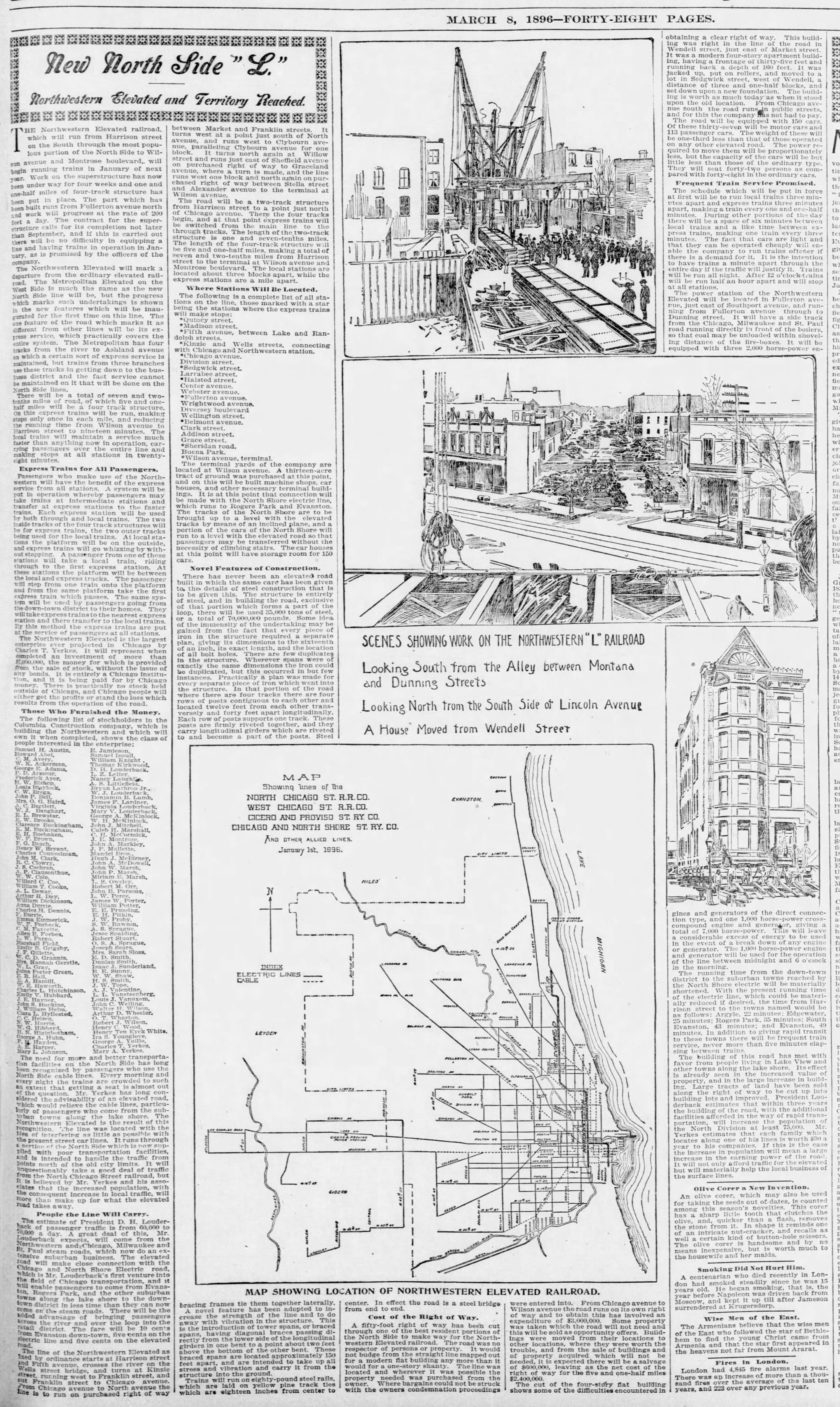

The Northwestern Elevated Railroad acquired two of those six identical dwellings in 1895 to create the right-of-way for their new elevated line. They put the buildings up for sale cheap to anyone who’d move or disassemble them. After removing the buildings, the railroad erected this section of track in early 1896–I believe it’s the oldest on the North Side.

1895 'For Sale' ad for the buildings in the way of the soon-to-be Northwestern Elevated line | Sketch of the back of 970 and 966 W. Montana, looking south from the alley, during the construction of the L tracks in 1896 | photo of the clearance for the L construction in 1896, from Fullerton looking south, CTA | "New North Side L", the Chicago Tribune, 1896

With no zoning codes requiring the separation of different types of land use and a loud elevated railroad as a new neighbor, within ten years the four remaining dwellings here were homes no longer–the Zymotechnic Institute and Siebel Brewing Academy moved in in 1901. Since renamed the Siebel Institute of Technology, it’s still in business–the oldest brewing school in the Americas.

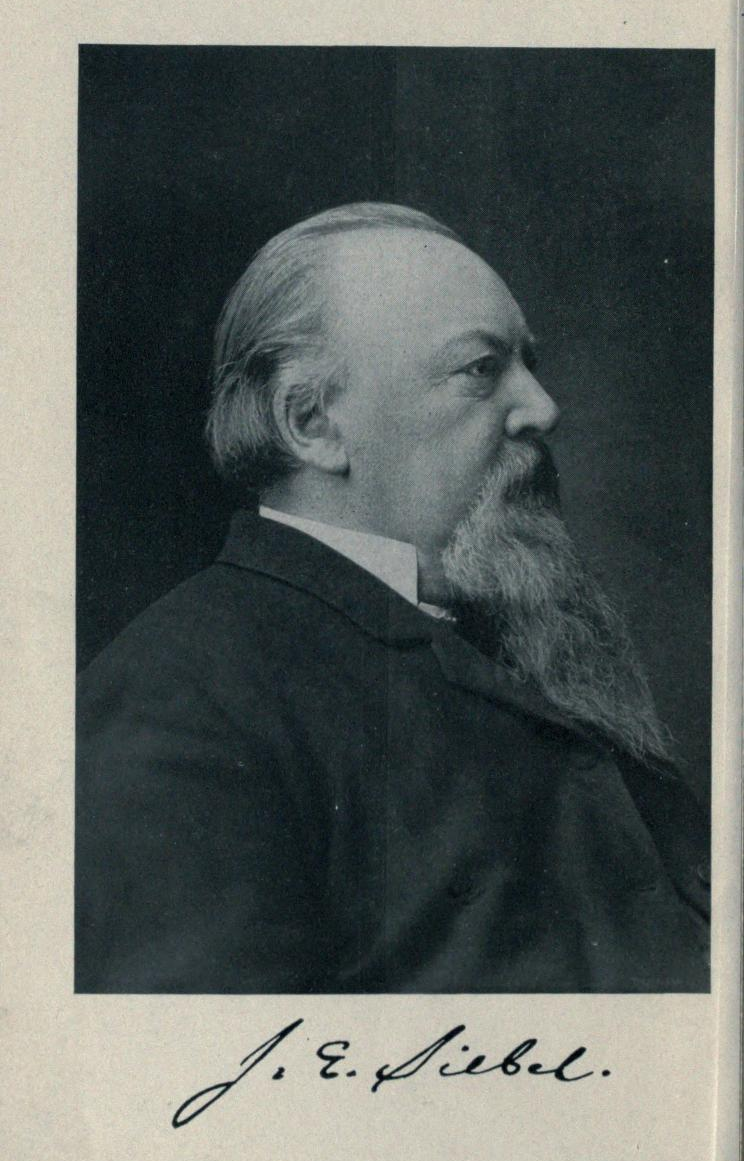

J.E. Siebel portrait from Compend of Mechanical Refrigeration and Engineering by J.E. Siebel, the Internet Archive | 1901 article on the opening of the new Siebel's Brewing Academy, the Chicago Tribune | 1903 article on a new class at Siebel's Brewing Academy, Abendposten, the Internet Archive | 1911 article on a Zymotechnic Institute gathering, the Chicago Tribune | 1913 German-language ad for Siebel's Brewing Academy, Abendposten, the Internet Archive

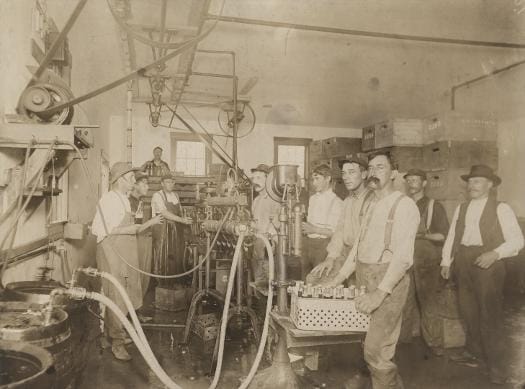

A German immigrant with a PhD, J.E. Siebel pushed forward his chosen field with remarkable energy and perseverance. He opened his first analytical lab in 1868, testing brewers' yeast samples for viability, wildness, and bacteria, but it took decades of tenacious persistence for Siebel to build serious traction—turns out, many 19th century brewers didn’t initially appreciate some nerd turning their art into science.

Siebel’s promotion of the science of fermentation and brewing was multipronged. He edited the Zymotechnic Magazine: Zeitschrift Für Gährungsgewerbe and Food and Beverage Critic, as well as the Western Brewer. He first attempted to open a brewing school—the Zymotechnic College—with a partner in 1884, but that school failed. All the while, Siebel’s consultancy and lab carried on, supplying breweries with yeast and testing samples (John Ewald’s various companies create some confusion around the actual founding date of the present-day Siebel Institute of Technology—sometimes they claim 1868, more frequently 1872).

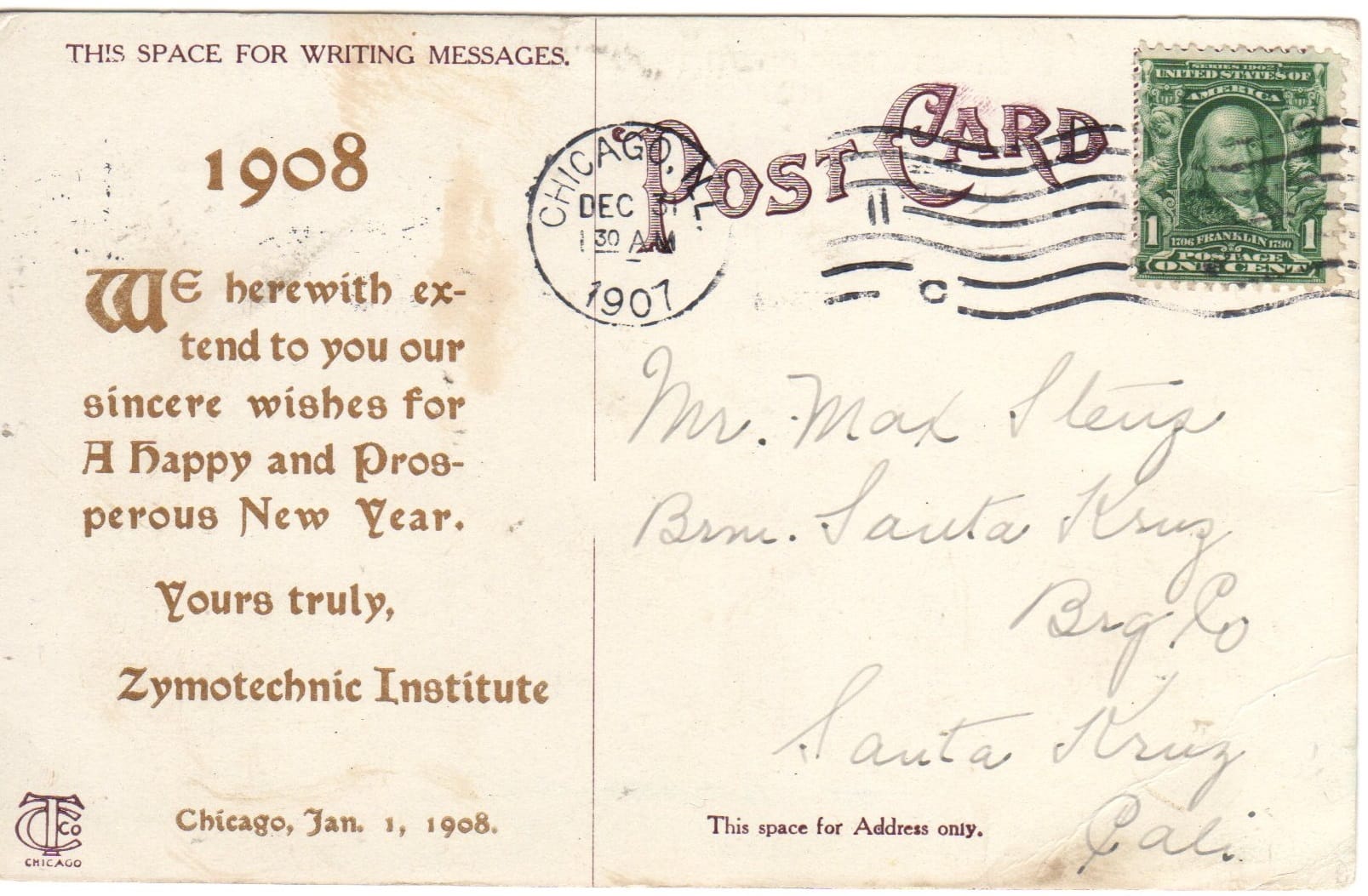

The five Siebel sons took over the family business in 1893 (J.E. continued to proselytize and research as, like, the zymotechnics zealot emeritus). Reportedly more commercially-minded than their dad, in 1901 the companies reincorporated as the Zymotechnic Institute, opened Siebel’s Brewing Academy, and moved here, to Montana Street in Lincoln Park, which was heavily German at the time.

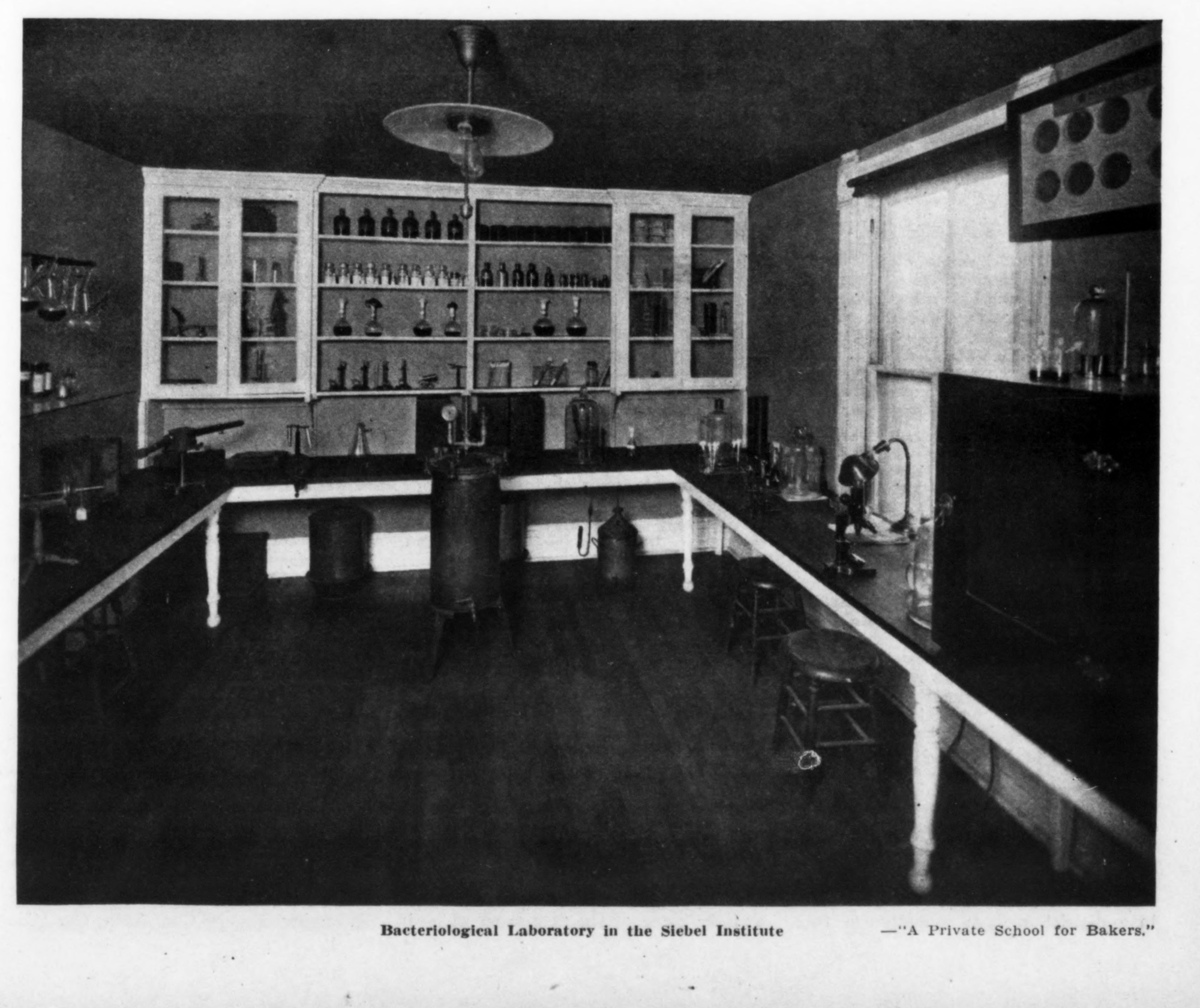

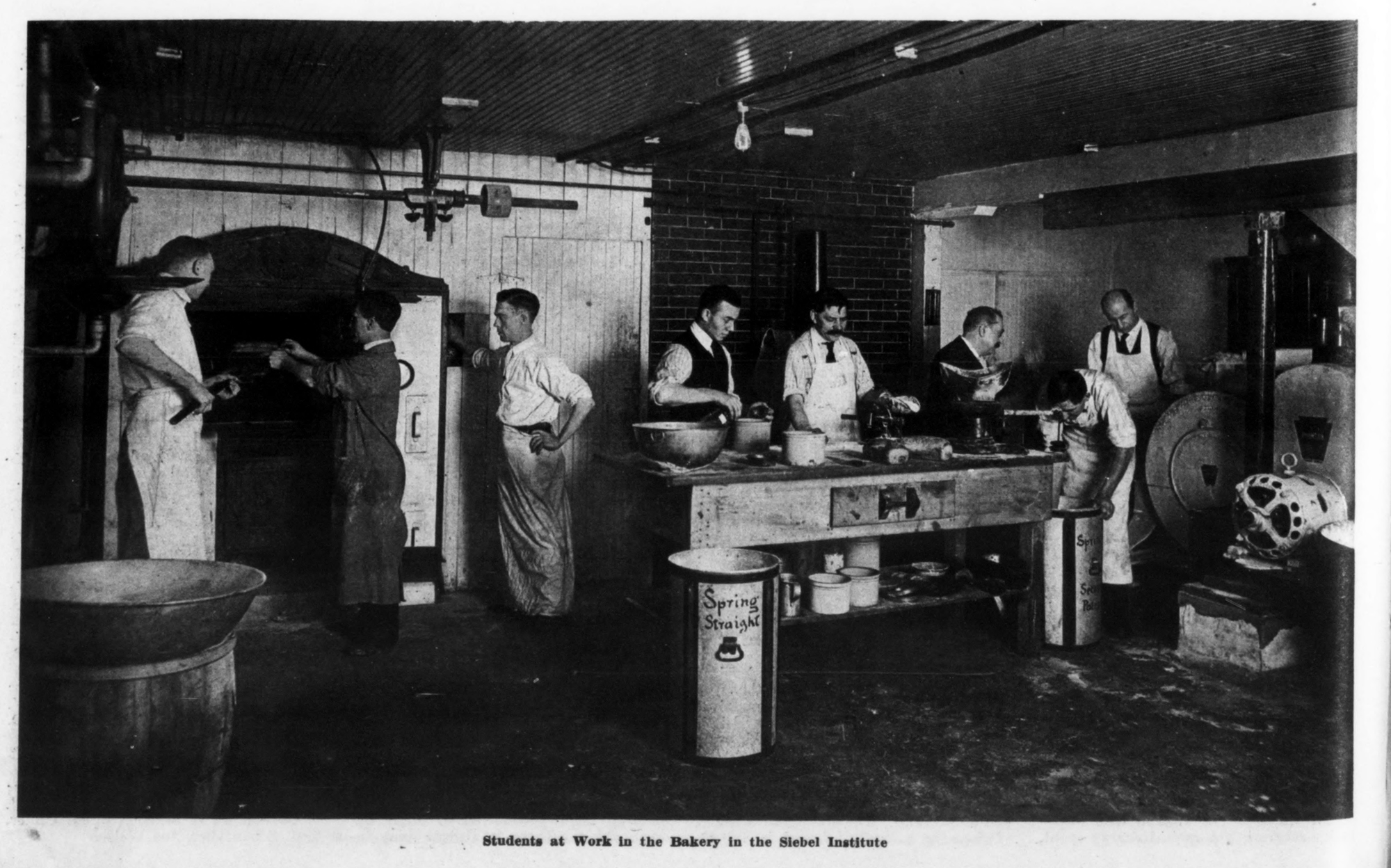

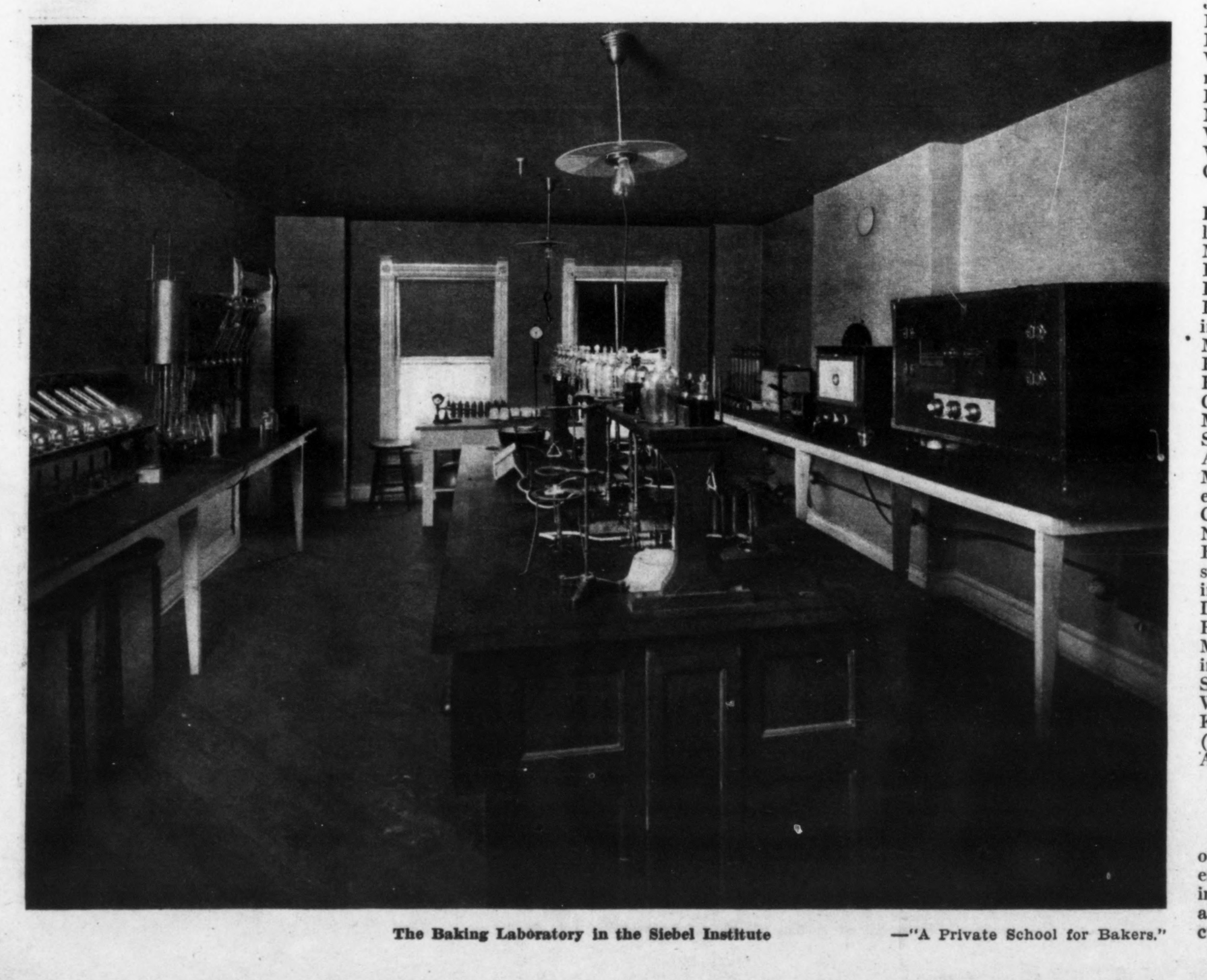

Zymotechnics aspired to more than just brewing. The science of productive fermentation combined aspects of chemistry, microbiology, and engineering–it was arguably a precursor to modern-day biotech–with applications for vinegar factories, distilleries, cideries, and bakeries. In 1903, the brewing school admitted 25 students. The Institute originally offered brewing, malting, and refrigeration courses, eventually followed by bottling, engineering, baking, etc.

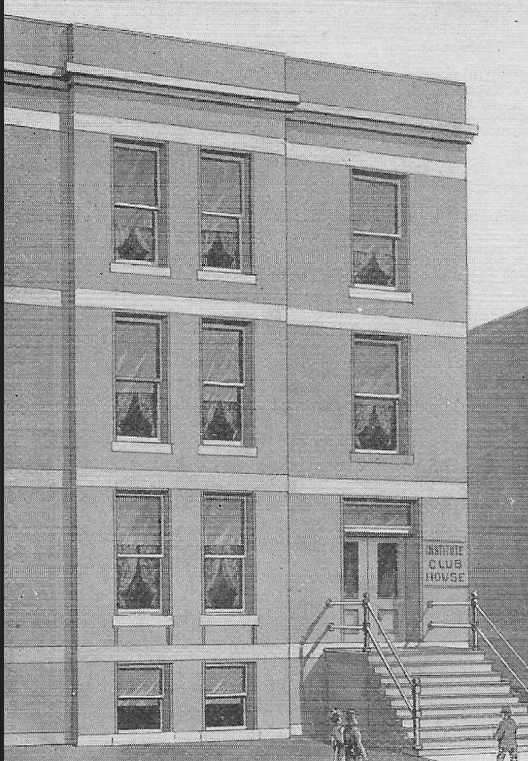

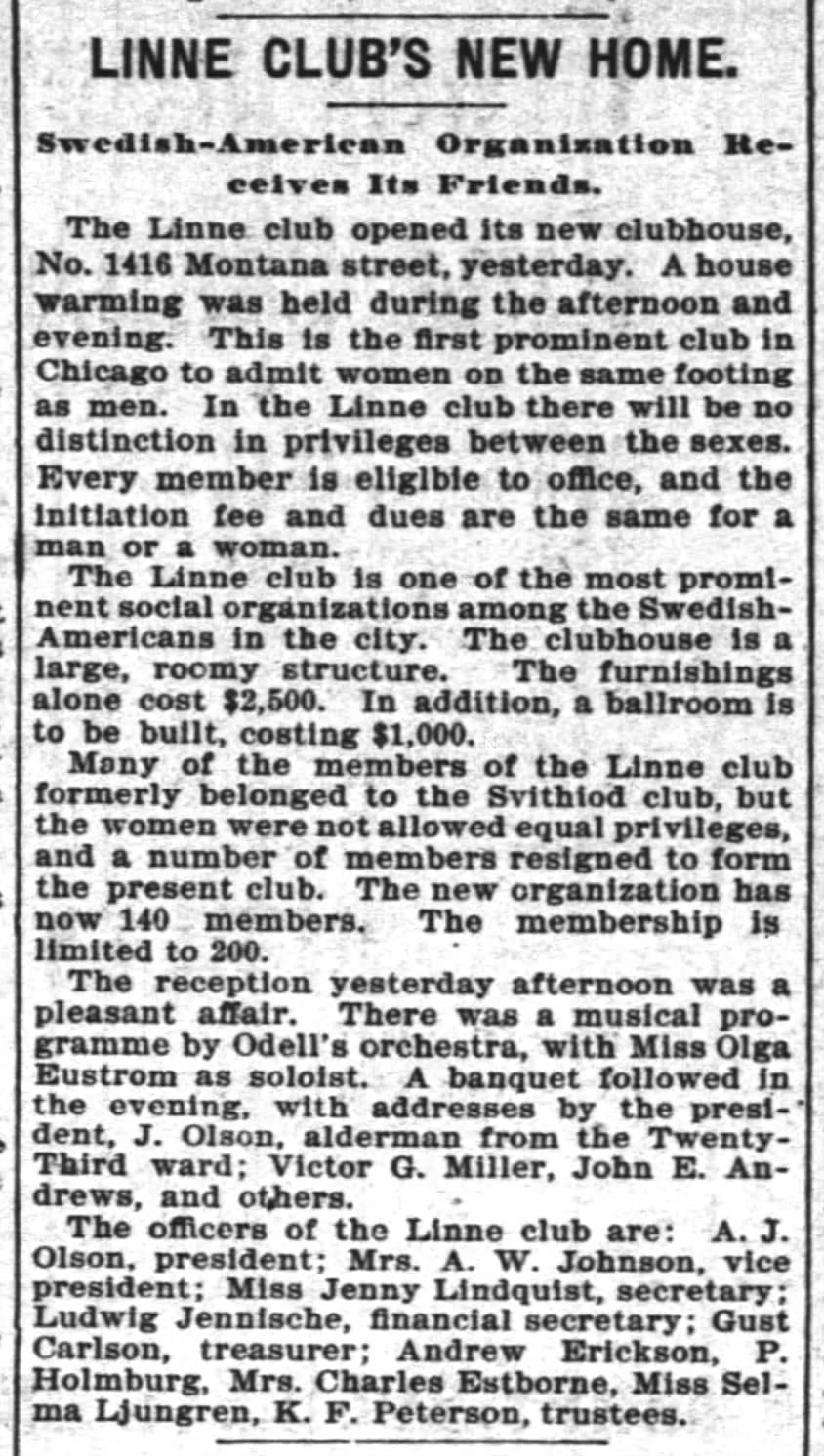

~1907 sketch of the Zymotechnic Institute Clubhouse, 970 W. Montana (then 1416 Montana) | 2024 photo of 970 W. Montana | 1900 article on the Linne Club's new location at 970 W. Montana, the Chicago Tribune | 1906 article on the Zymotechnic Insitute's commencement in the clubhouse at 970 W. Montana, the Western Brewer, HathiTrust

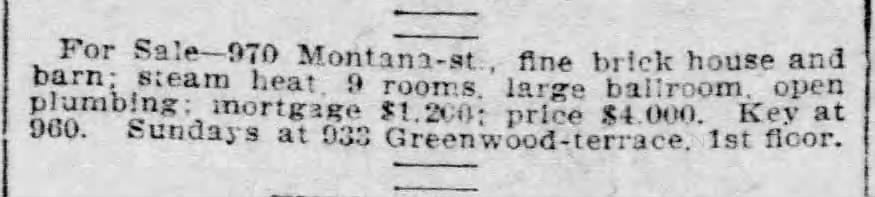

970 W. Montana served as the Institute’s clubhouse, as well as the residence for one of the Siebel sons. In 1910, Fred and Amelia Siebel lived here with their three kids and a servant. The Institute wasn’t the first organization to use the building as a clubhouse–in 1900 the Linne Club moved in, a Swedish-American club and the “first prominent club in Chicago to admit women on the same footing as men”. They converted part of the space into a ballroom.

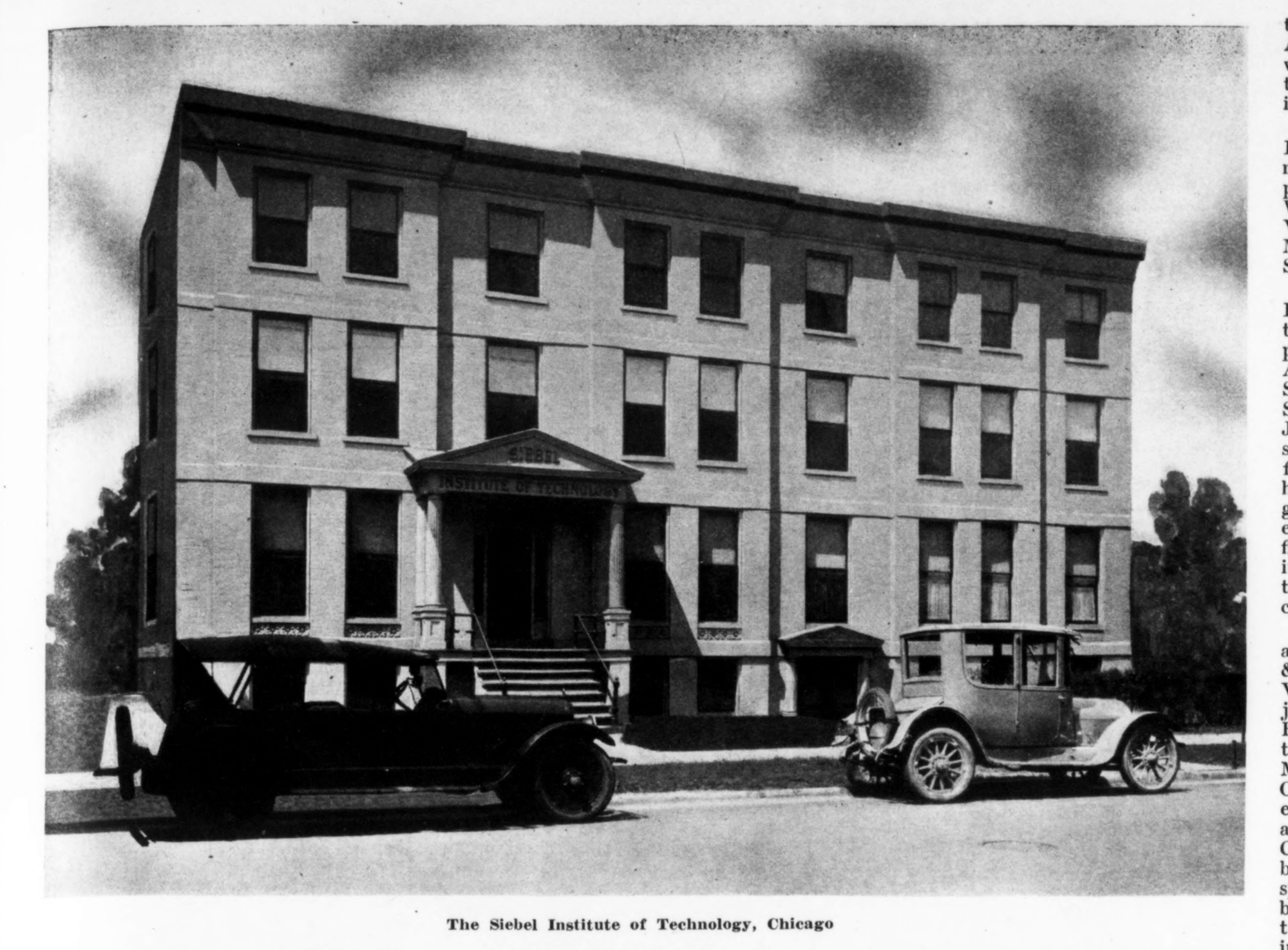

~1907 sketch of the Zymotechnic Institute and Siebel's Brewing Academy | 1909 interior view, ICHi-025667, Chicago History Museum | 1920 exterior photo of the Siebel Institute main building and the bacteriological lab inside, Northwestern Miller, the Internet Archive

The Siebels combined the three former dwellings east of the L tracks, 958 to 966 W. Montana, into a single building with labs, breweries, and bakeries in 1907–I think it’s pretty likely that this was the occasion they published this postcard for.

1911 'For Sale' ad for 970 W. Montana, the Institute clubhouse and Fred Siebel's home, the Chicago Tribune

The Siebels decided pretty quickly that they didn’t need–or couldn’t afford–a clubhouse, and put 970 W. Montana up for sale in 1911. The “For Sale” ad even mentions the ballroom the Swedes built into it. A 1922 renovation likely made the building more appropriate for manufacturing, and for 50+ years this building housed a parade of various light manufacturing companies. Woodworking companies in the 1920s. Tool and die companies in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. Metal fabricators in the 1960s. Electrical engineering in the 1970s.

Various help wanted and 'For Sale' ads for businesses in 970 W. Montana (and one article about a fire): 1926, for sale/rent as a woodworking shop; a minor fire in 1937; EPA Manufacturing ad, 1942; C-B Tool help wanted ad, 1946; 1957 H. & S. Swanson's Tool Co. help wanted ad; 1959 Montana Metal Products help wanted ad; 1972 help wanted ad for an electrical engineer for Pollution Monitors, Inc.

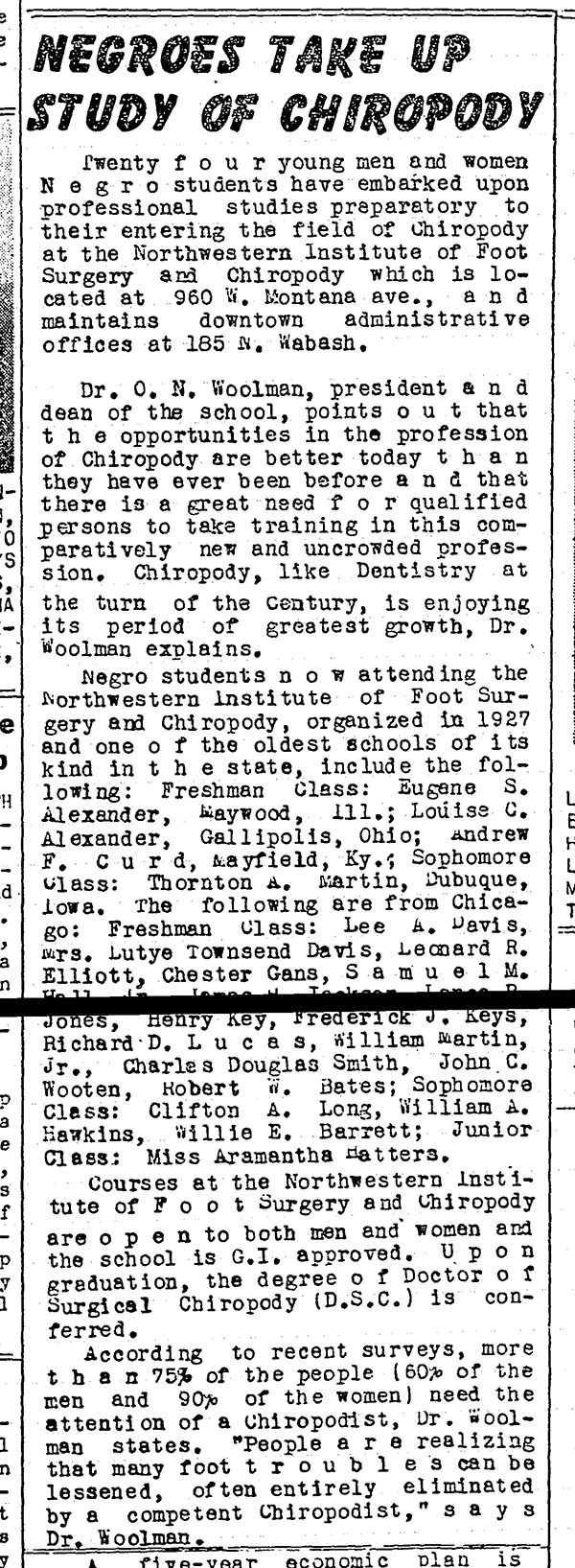

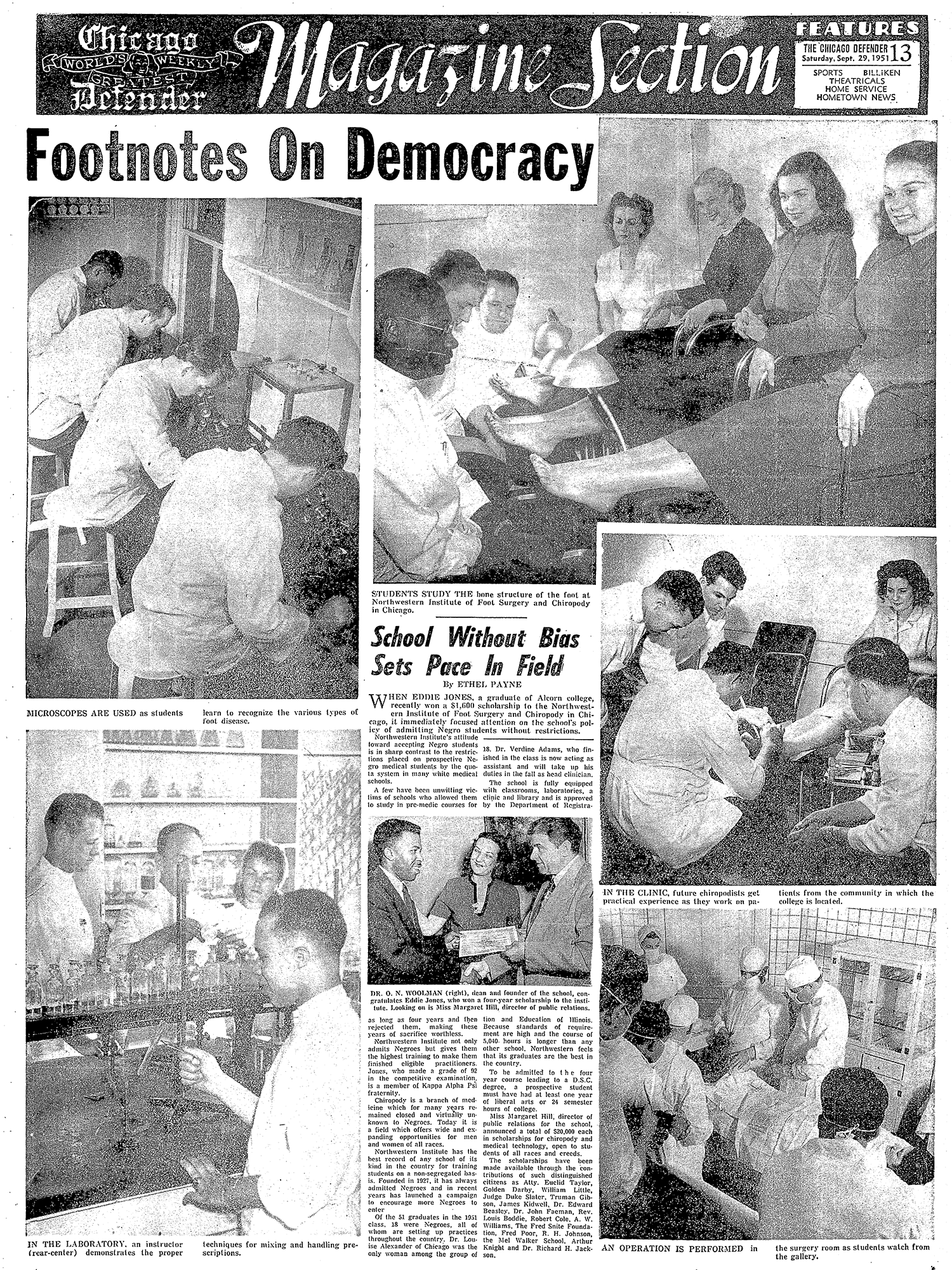

By that point, 970 W. Montana had outlived the main Siebel buildings on the other side of the tracks. The Siebel Institute survived Prohibition by falling back on baking and other zymotechnic applications (even if they’d long since abandoned that word), and within days of Prohibition’s end they were offering up brewing courses again. For whatever reason, in 1946 the Siebel Institute put the building up for sale, and within a year–perhaps attracted by the built-out lab space–the Northwestern Institute of Foot Surgery and Chiropody had moved in. The Siebel Institute eventually moved to a location on Peterson on the far north side (fittingly, now the home of Alarmist Brewing). I couldn’t find much on that podiatry school, but one notable thing is that it accepted Black students from the day it opened in 1927–a good example of how “it was a different time” is often a cop out.

1920 photos of the bakery and bakery lab, Northwestern Miller, the Internet Archive | 1934 Siebel baking school ad | 1933 Siebel brewing course ad | 1945 analysis ad, Northwestern Miller, the Internet Archive | 1946, building for sale ad | 1948 ad for the Northwestern Institute of Foot Surgery & Chiropody, the Chicago Tribune | 1947 and 1951 articles about the Northwestern Institute of Foot Surgery & Chiropody in the Chicago Defender

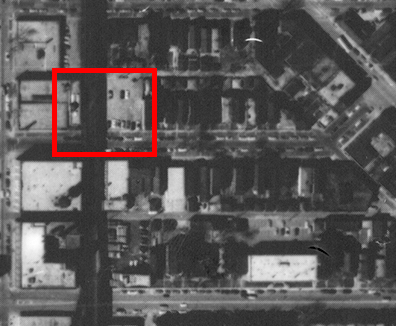

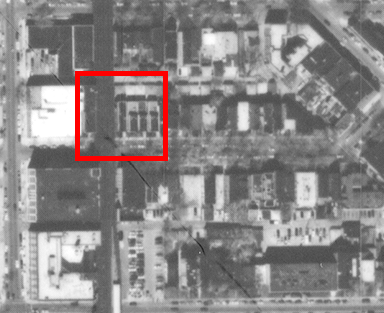

At some point, the Northwestern Institute of Foot Surgery closed, and between 1963 and 1970 the main old Siebel building was demolished. The lot sat vacant, used as a parking lot, until the mid 1980s. Out of the original six identical dwellings on the north side of W. Montana Street, one remained.

1923 Sanborn Map | 1938 aerial, Illinois State Geological Survey | 1950 Sanborn Map | 1970 aerial, Northeastern Illinois Air Photo Archive, CMAP | 1980 aerial, Northeastern Illinois Air Photo Archive, CMAP | 1985 aerial, Northeastern Illinois Air Photo Archive, CMAP | 1990 aerial, Northeastern Illinois Air Photo Archive, CMAP

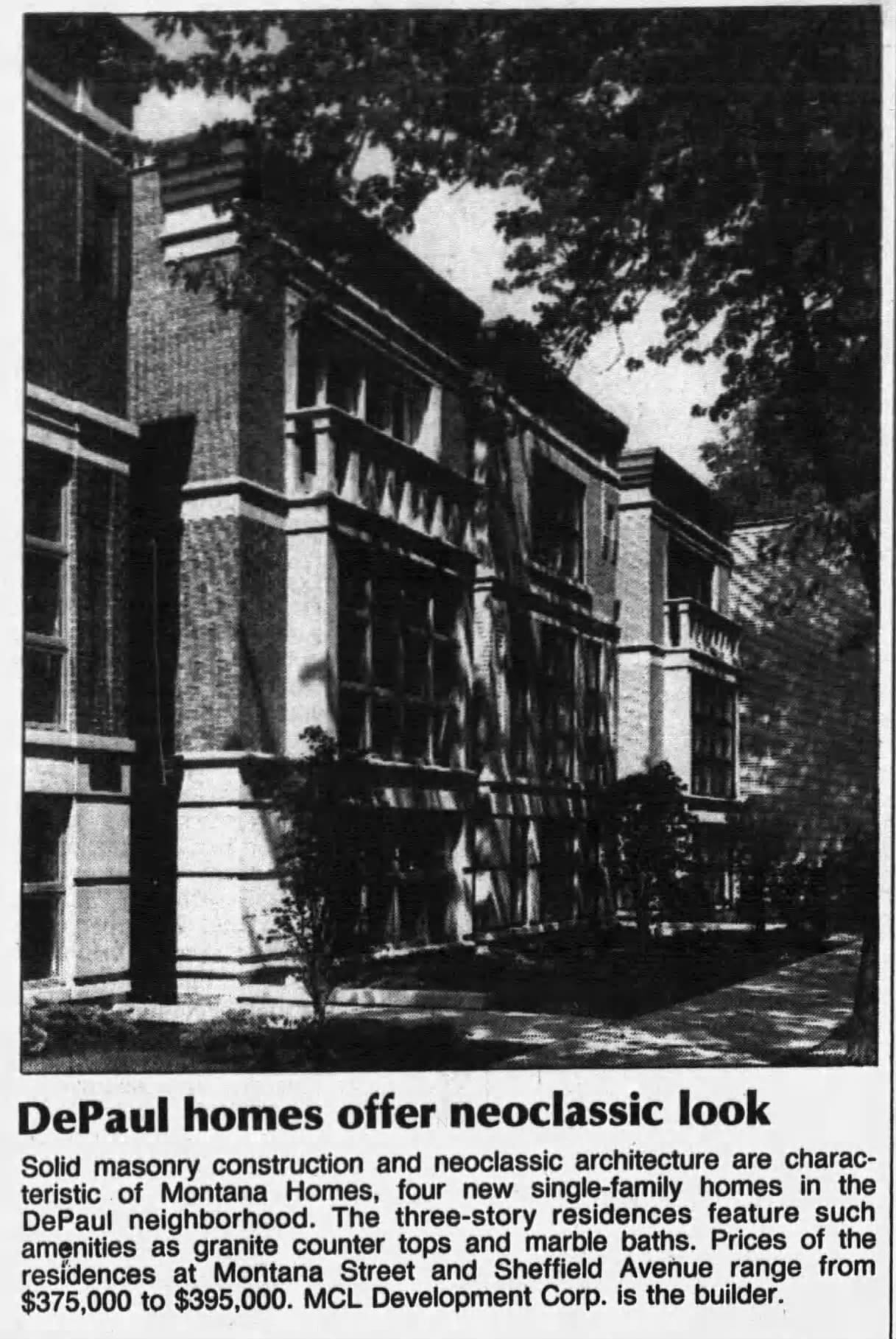

The diverging fates of the two Siebel Institute buildings on either side of the L is one story of Lincoln Park gentrification writ small, with upwardly mobile young professionals moving into the neighborhood for the first time in decades in the 1980s and DePaul University expanding. On the old Siebel Institute’s vacant lot, four large single family homes were built by MCL Development, completed in 1988 and sold for the equivalent of $1m each today. 970–the survivor–was converted into loft office space in the mid-1980s, and a variety of office tenants passed through here. Most notably, the Windy City Times, Chicago’s LGBT paper, had its office in 970 from the late 1980s into the mid-1990s.

1987 ad for the homes for sale on the old Siebel Institute site, Chicago Tribune | 1989 article on the Montana Homes, Chicago Tribune | 2002 for sale ad for 962 W. Montana, Chicago Tribune | 962 W. Montana, 2024

970 W. Montana rehabbed office space for lease, Chicago Tribune | 1989, Windy City Times salutes the achievements of the 8th Annual Women's Film & Video Festival | 970 W. Montana visible from the L tracks in 1989, Ronald J. Sullivan, Northwestern Transportation Library| 1995 Windy City Times help wanted ad, Chicago Tribune | 1996 ad in the DePaulia

DePaul University bought the building in 1997. Bringing things incredibly full circle, the university sold the building in 2020 and the new owner, after more than a century, returned the upper floors to residential use. In an example of how silly our zoning and planning processes can be, the new owners needed planning permission from the alderman to return the building–which had been built as a home nearly 140 years prior–to residential use. The office space on the first floor remains available for rent.

While their one-time home has either been demolished and turned into apartments, the Siebel Institute itself is still going strong. J.E. Siebel’s descendants cashed out in 2000, but I imagine the school benefited from the craft brewing boom of the 2000s and 2010s. Located in the West Loop since 2020, they also have a sister campus in Munich.

I suspect the specificity of the main Siebel Institute building doomed it. The flexibility to convert 970 W. Montana between commercial, industrial, and residential uses kept the building productive, full, and upright over the last 135+ years. The laboratories and larger spaces of the main Siebel building, on the other hand, was probably more challenging and more expensive to convert as needs changed in the 1960s. Being a manageable size with a relatively normal layout can be an underrated asset.

Production Files

Further reading:

- The Siebel Institute's history in their own words, part one and part two

- The uses of life: a history of biotechnology by Robert Bud

- Beer: a history of brewing in Chicago by Bob Skilnik

- Siebel’s Manual for Bakers and Millers

- "A Private School for Bakers" in the Northwestern Miller, 1920

- The rental listing for the office space on the first floor of 970 W. Montana

A note on addresses: the buildings occupied by the Siebel Institute were 1416 to 1424 Montana before Chicago's streets were renumbered in 1909. The clubhouse building, now 970 W. Montana, was 1416 Montana. The main Siebel buildings were in 1424 (eventually expanding to 1426) to 1422 Montana, which were renumbered to 958 to 966 W. Montana.

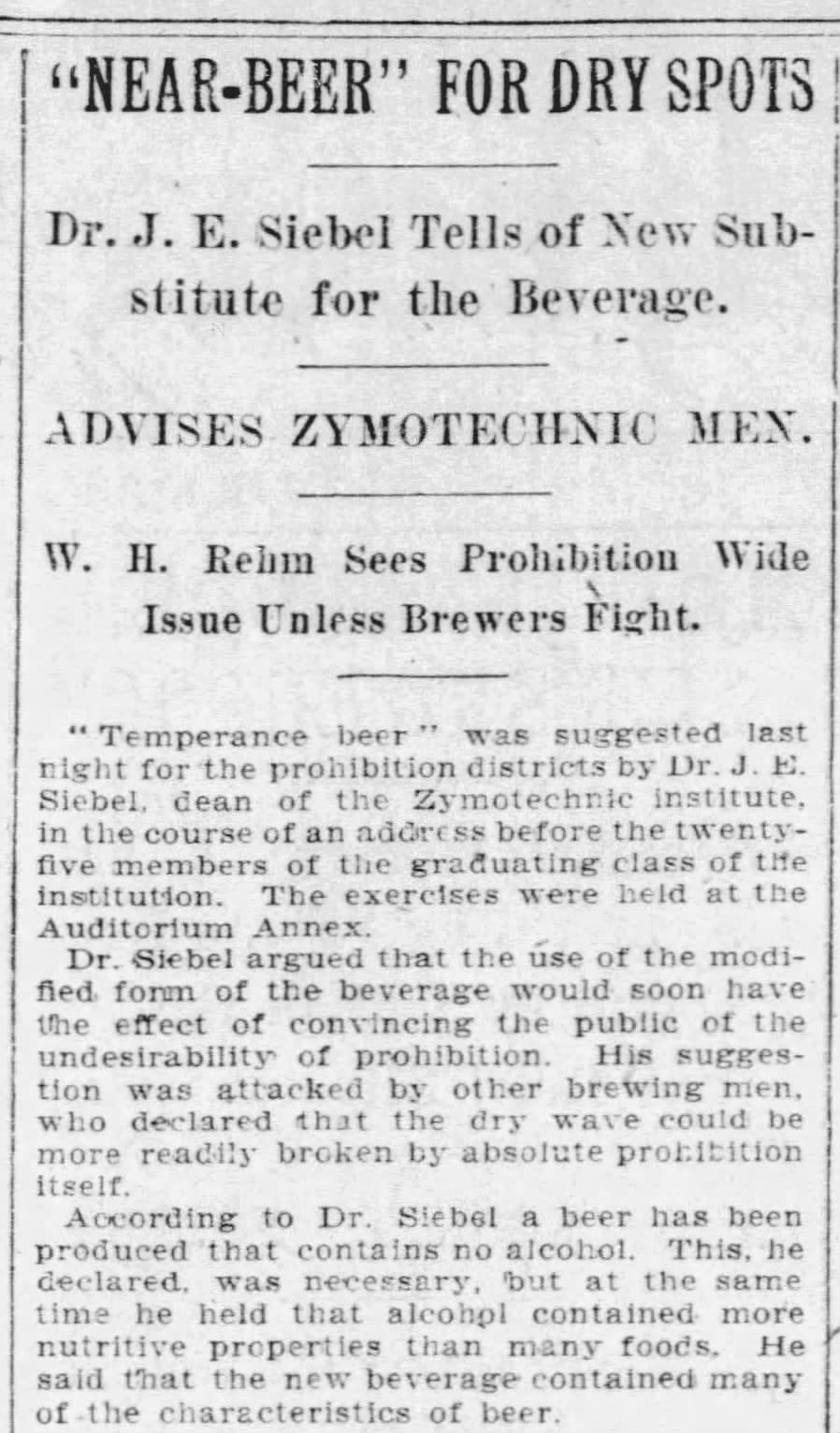

J.E. Siebel recognized the risk the temperance movement posed to his business and his passion. He worked multiple angles to push back against prohibition advocates, including developing non-alcoholic beer, proposing it as an option for dry communities.

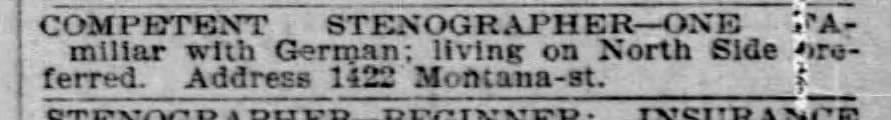

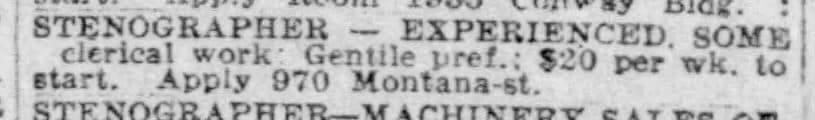

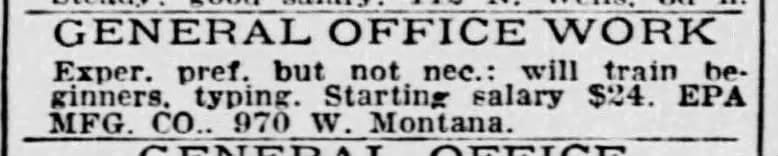

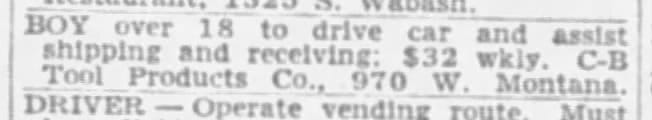

A few things that stood out in various 'Help Wanted' ads for the establishments in 958-970 W. Montana:

- The Siebels preferred to hire people with a German background.

- I was taken aback by that ad from 1924 that specified "gentile preferred" (by that point I believe the Siebel Institute was no longer in the building)–you would've been working as a stenographer for antisemites who paid only $19k a year in 2024 dollars.

- That general office work job at EPA MFG in 1943 paid the equivalent of $23k a year.

- A job at C-B Tool Products in 1945 driving their car and assisting shipping and receiving paid the equivalent of $29k a year in 2024 dollars.

1907 F.P. Siebel help wanted ad | 1903 stenographer ad, German familiarity preferred | 1924 stenographer wanted ad, "Gentile pref." | 1943 EPA MFG help wanted ad | 1945 C-B Tool help wanted ad

I made these .gifs with the historic aerials and the fire insurance maps.

This is where I took the photo from.

Member discussion: