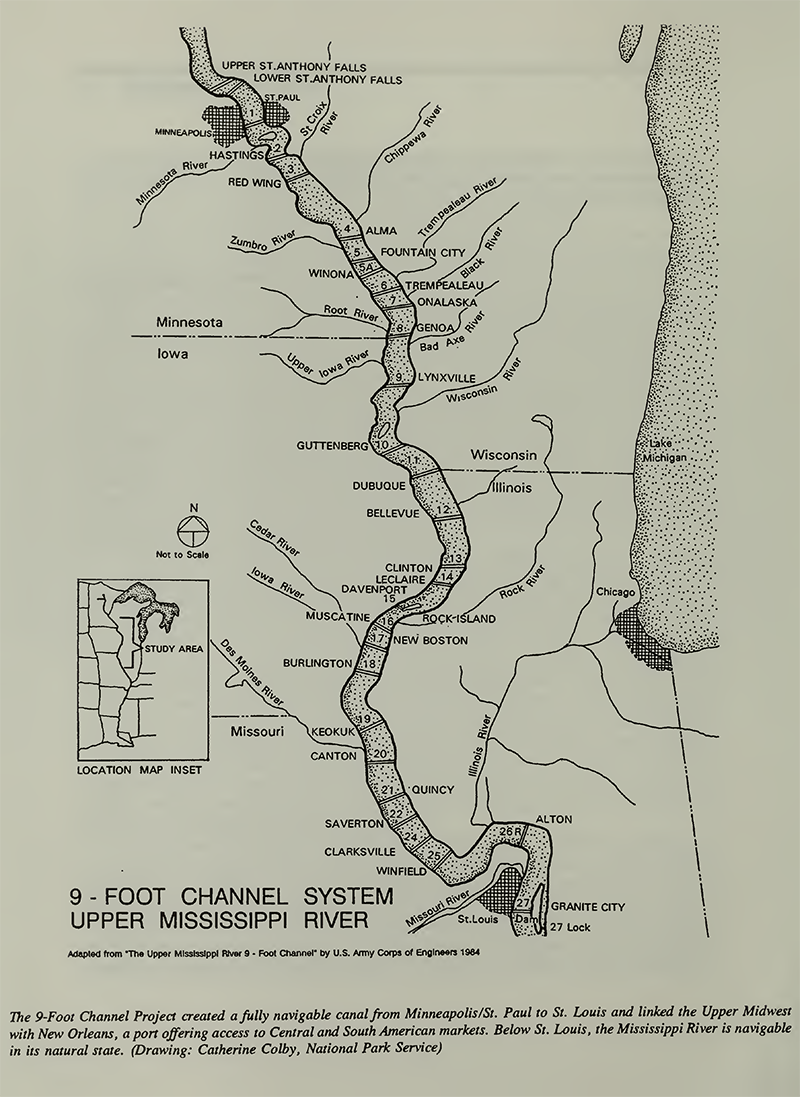

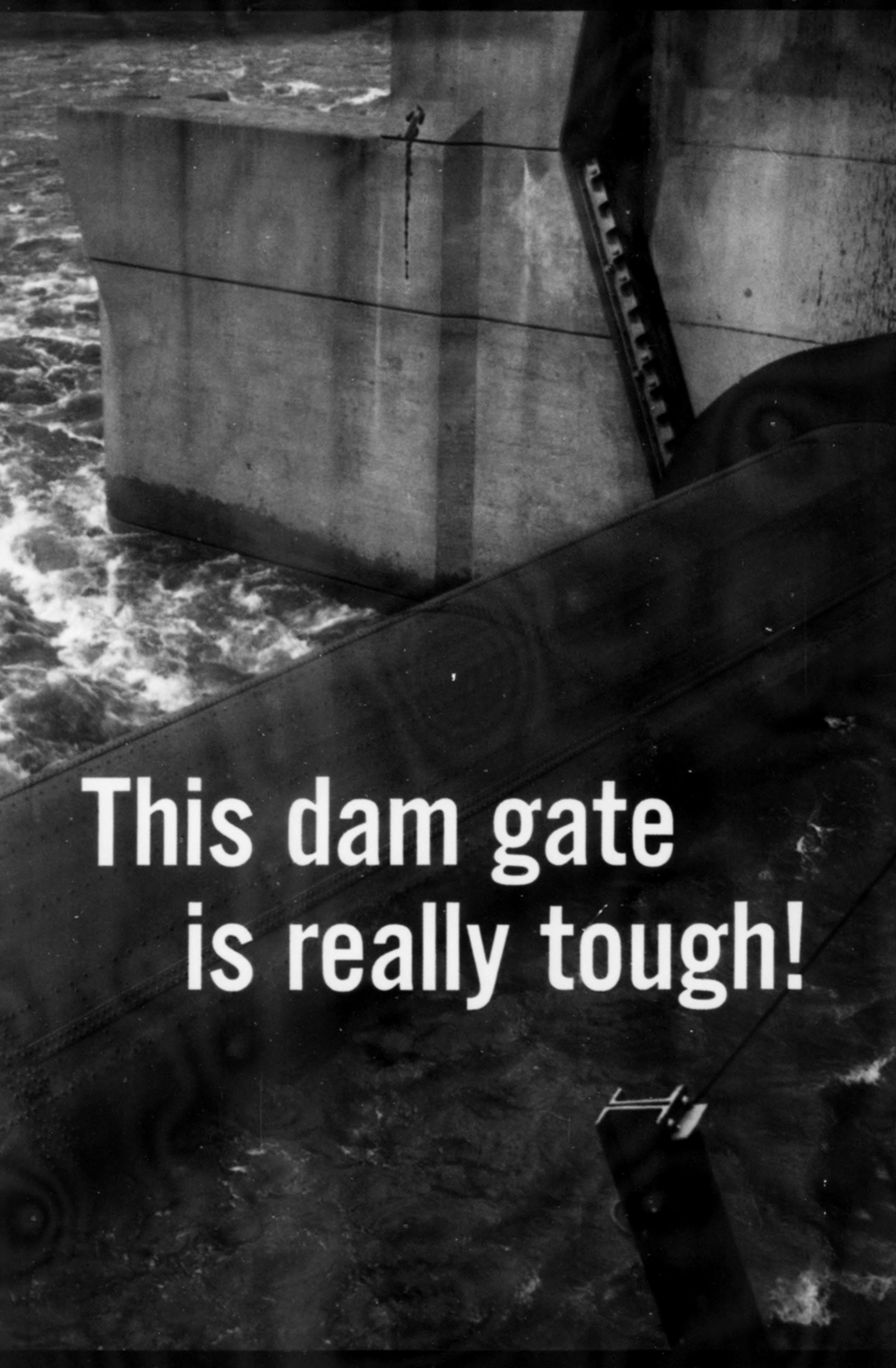

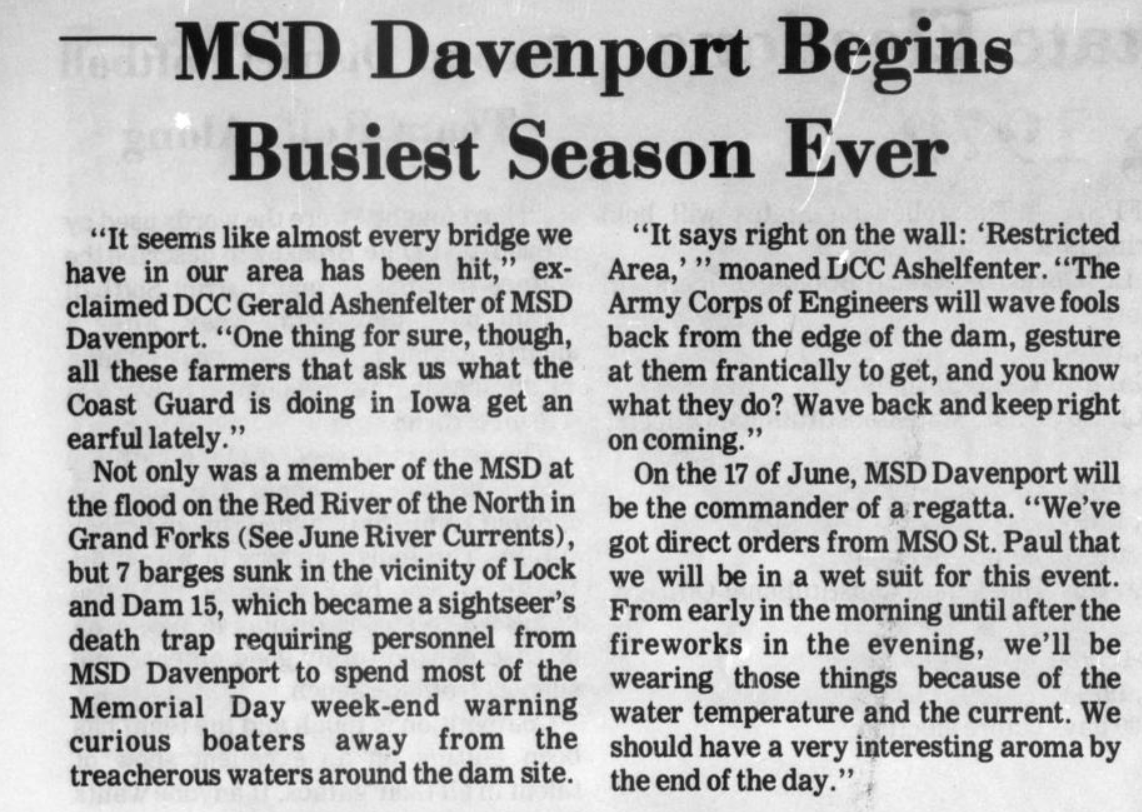

The first dam conceived as part of the massive engineering project that tamed the Upper Mississippi River, Dam No. 15 between Davenport and Rock Island is the longest roller dam in the world. Not that that’s saying a whole lot; it’s more of a Major League Baseball kind of stat, along the lines of Mark Grace holding the record for the most hits in the 1990s - an accomplishment that is both impressive in vacuum but also heavily indebted to randomness, sequencing, and the idiosyncrasies of a particular time period. The US Army Corps of Engineers intended Lock and Dam No. 15 to serve as the prototype for the whole 9-foot Channel Project that would build 29 locks and dams on the Upper Mississippi in the 1930s, but large roller dams never gained widespread adoption, for reasons ranging from their danger as “drowning machines” (they’re called roller dams because of the rolling [and deadly] wave action they create at the foot of the dam) to their limited value beyond easing navigation and diverting water for irrigation.

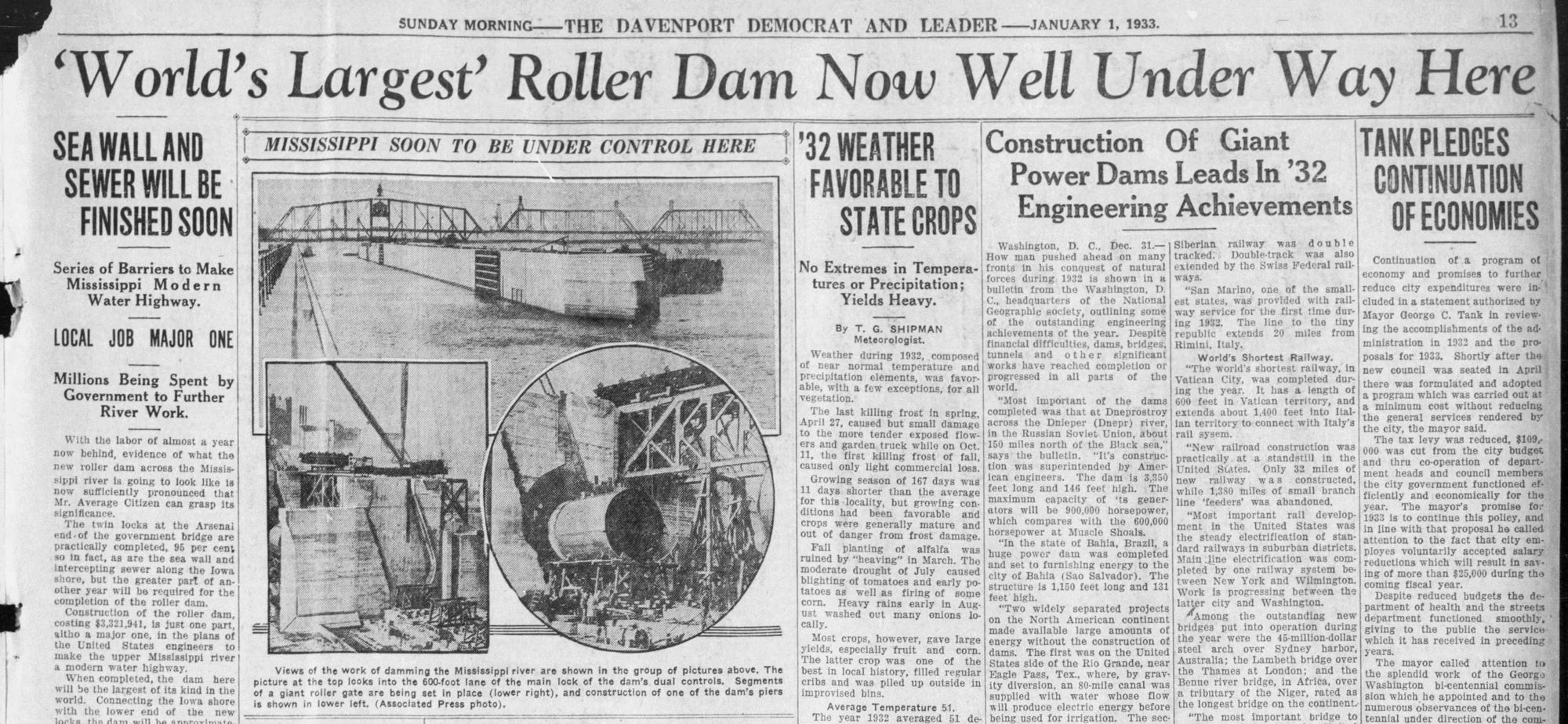

The 9-foot Channel Project was the Upper Mississippi’s greatest manmade transformation - and, under the Roosevelt Administration, the project itself transformed immensely. Begun as a technocratic US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) navigation project that aimed to support Midwestern farmers with a cheap, reliable river shipping system, under FDR it became a massive public employment program. The initial USACE plans called for the Rock Island District to build Lock and Dam No. 15 first, a model for the 28 other locks and dams that would turn the Upper Mississippi into a slack-water navigation system, a series of deep river pools, connected by locks, that would (cheaply, competitively) bring Midwest agricultural goods to the world. In planning since the 1920s, construction here began in 1931, but upon taking office FDR scaled the program massively. To keep the Midwest employed during the Great Depression, the federal government launched construction on all 29 locks and dams basically simultaneously, rather than the original plan of building a few at a time.

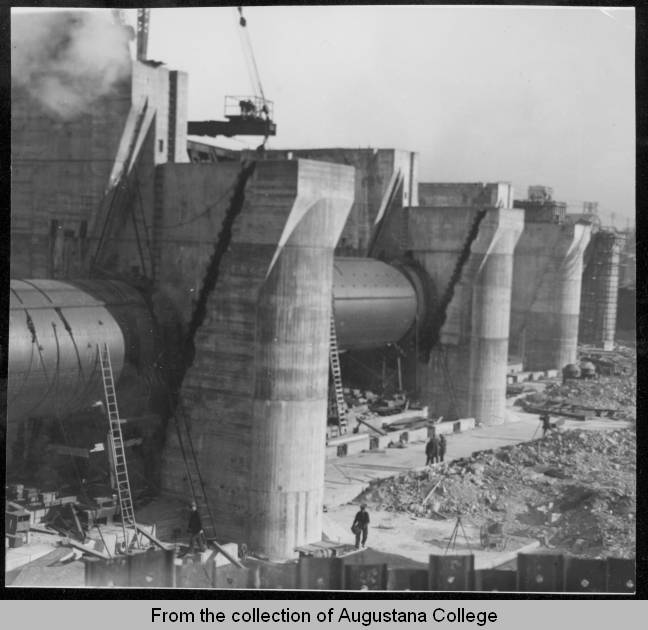

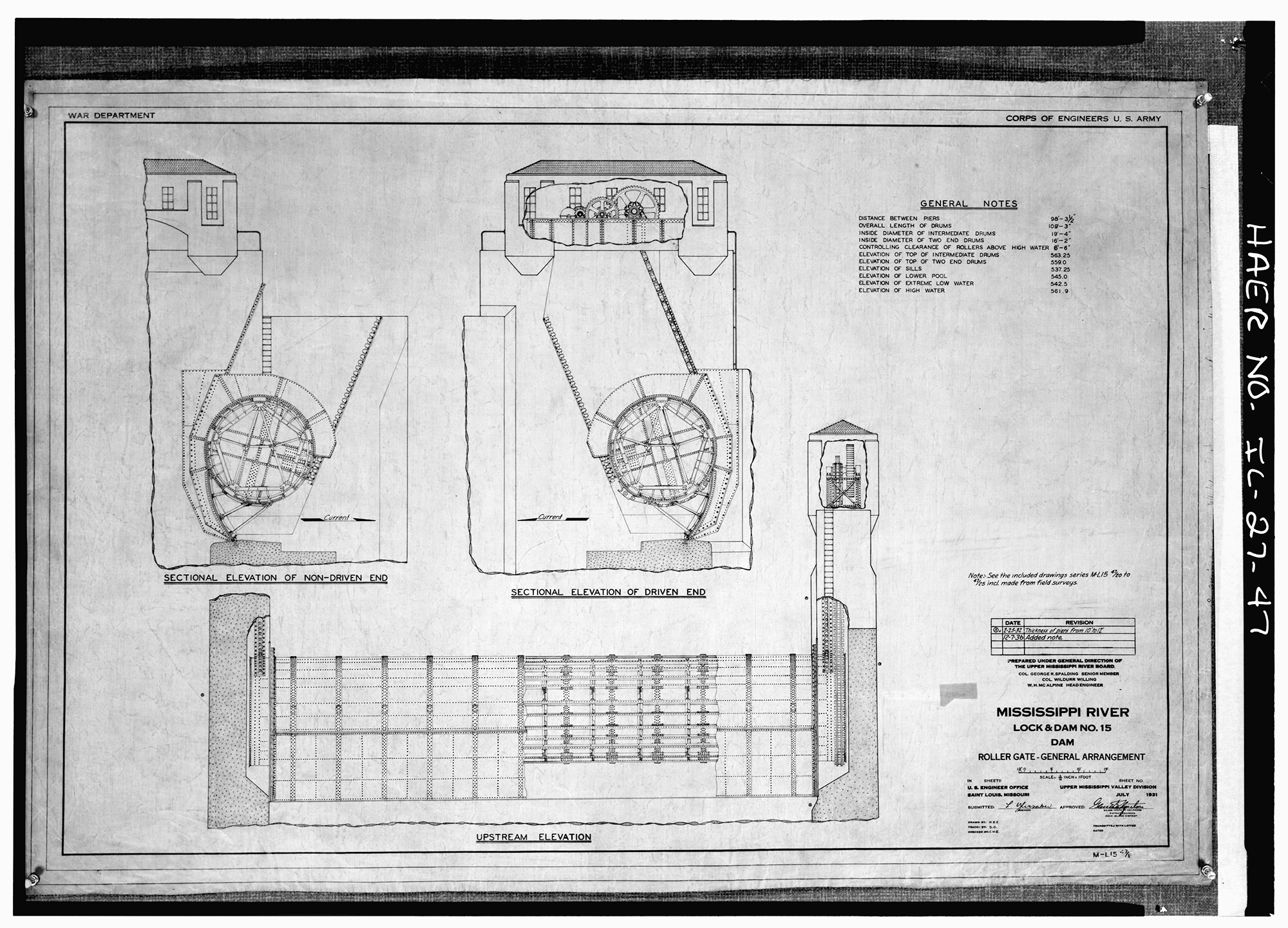

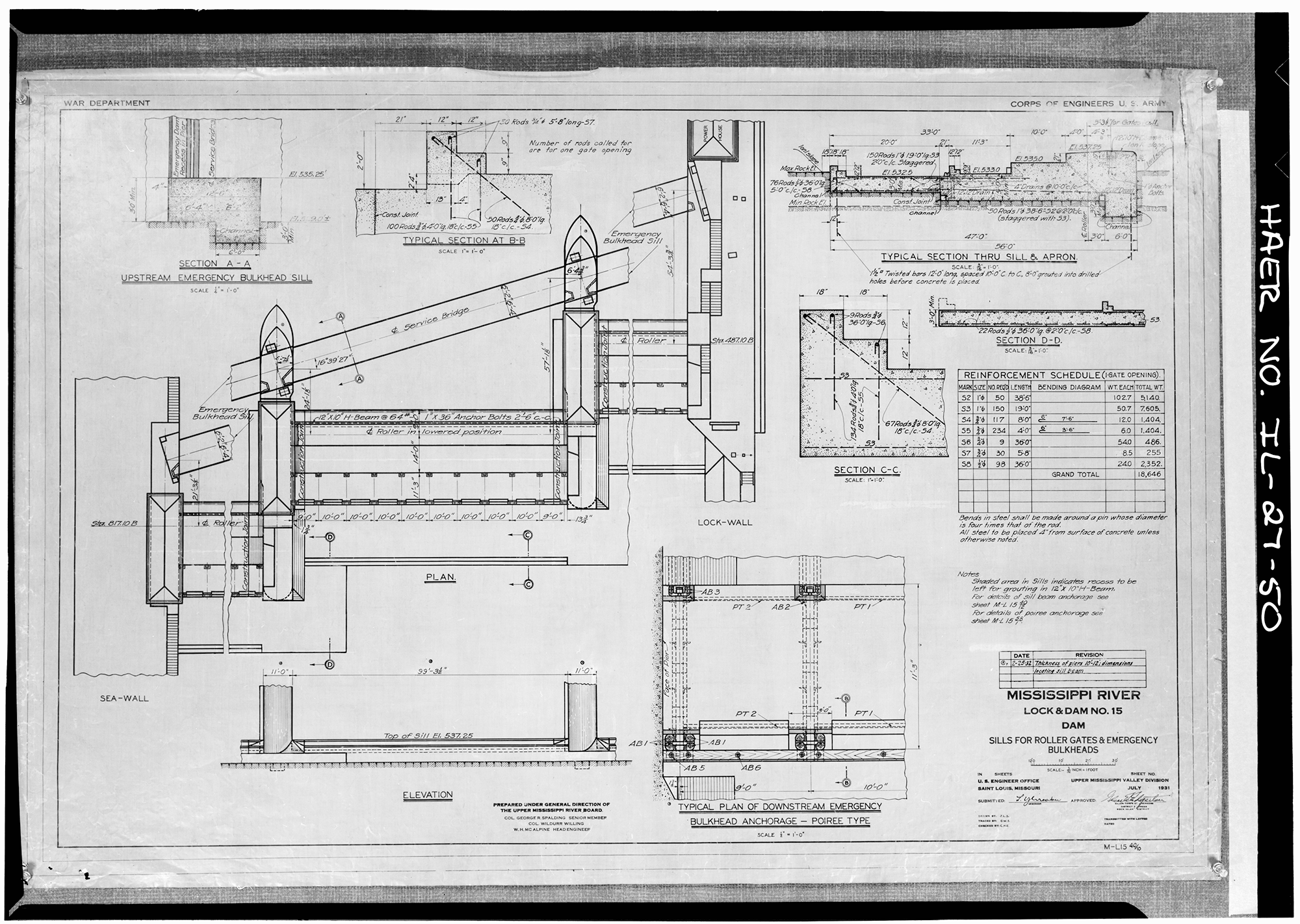

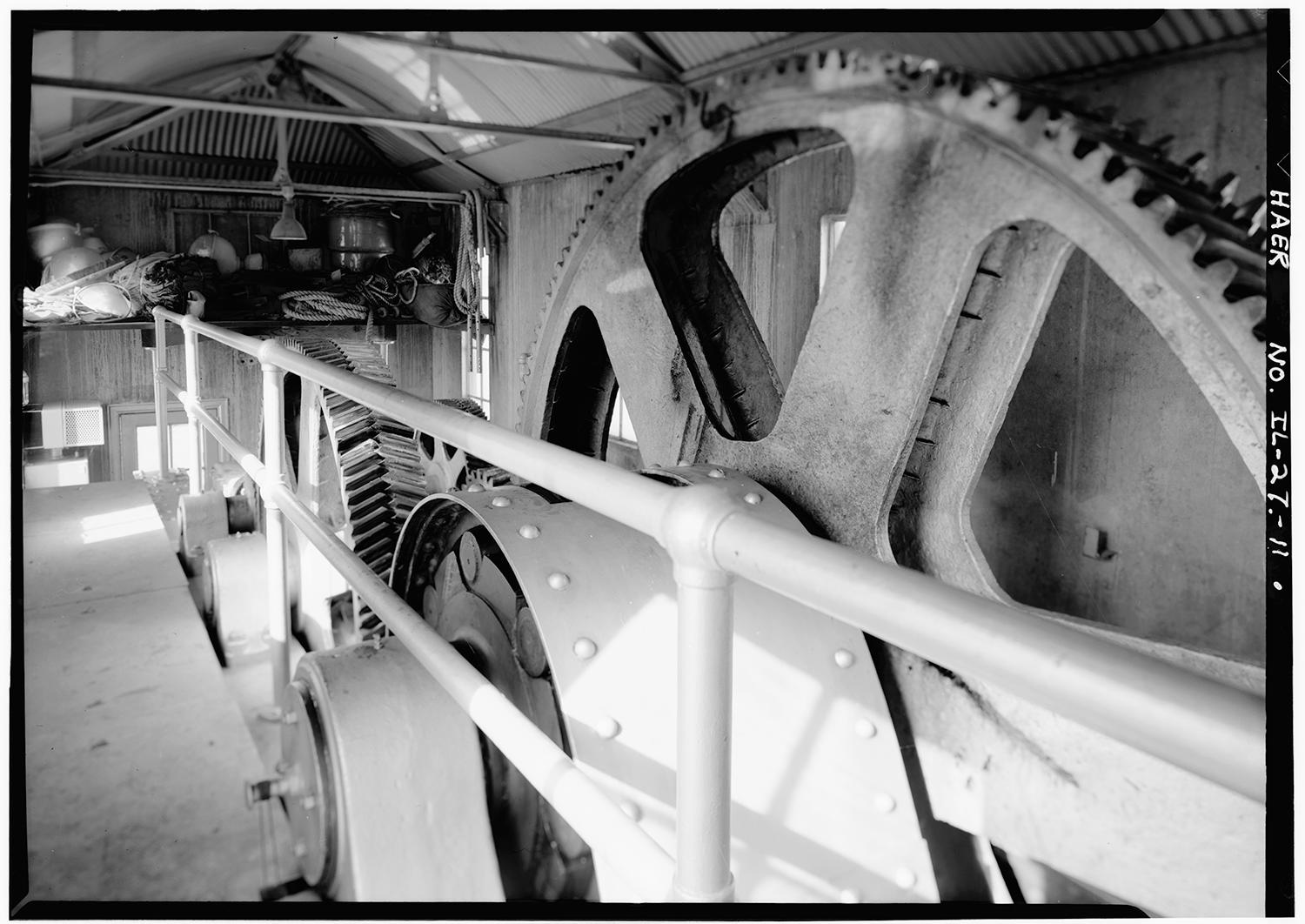

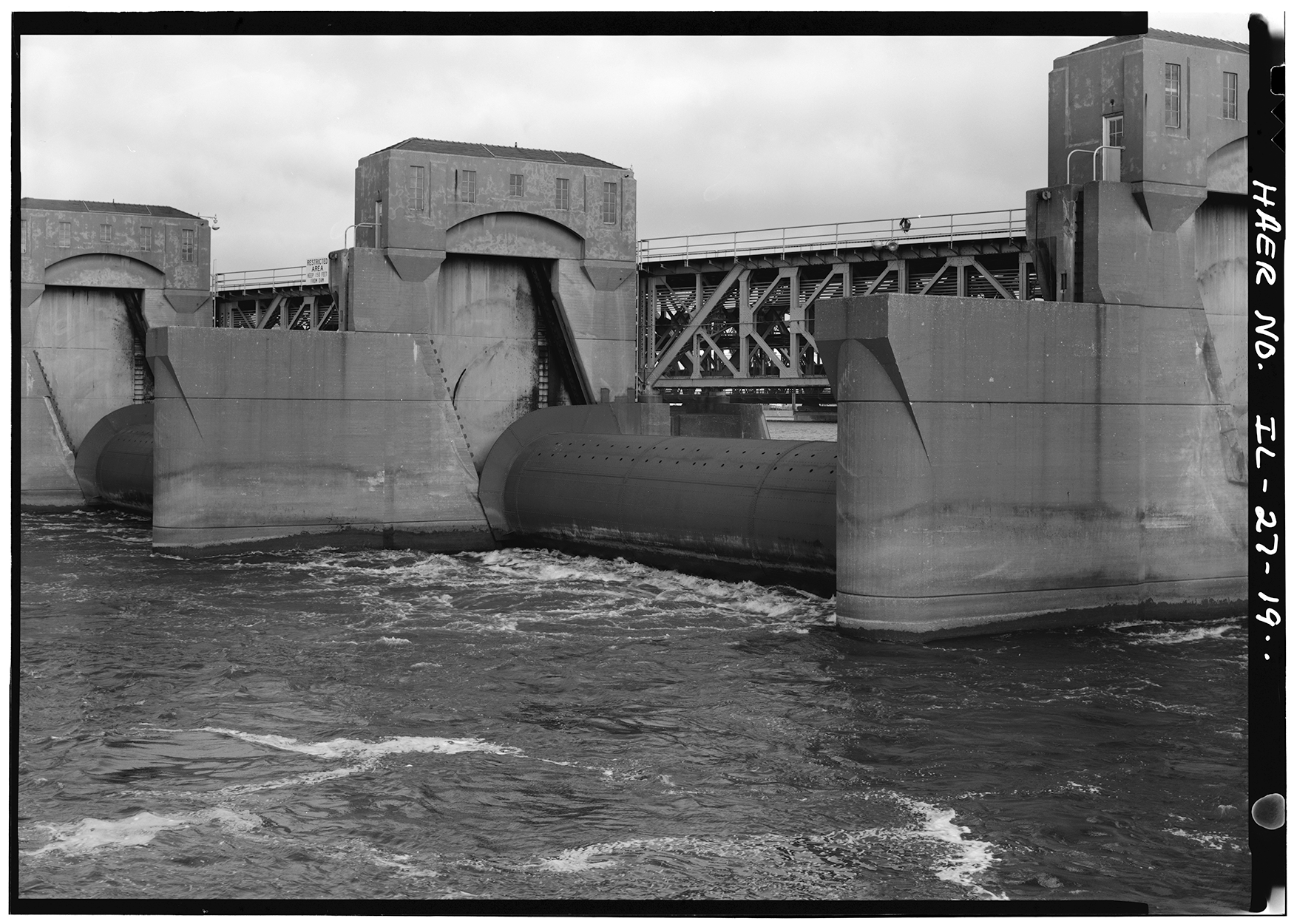

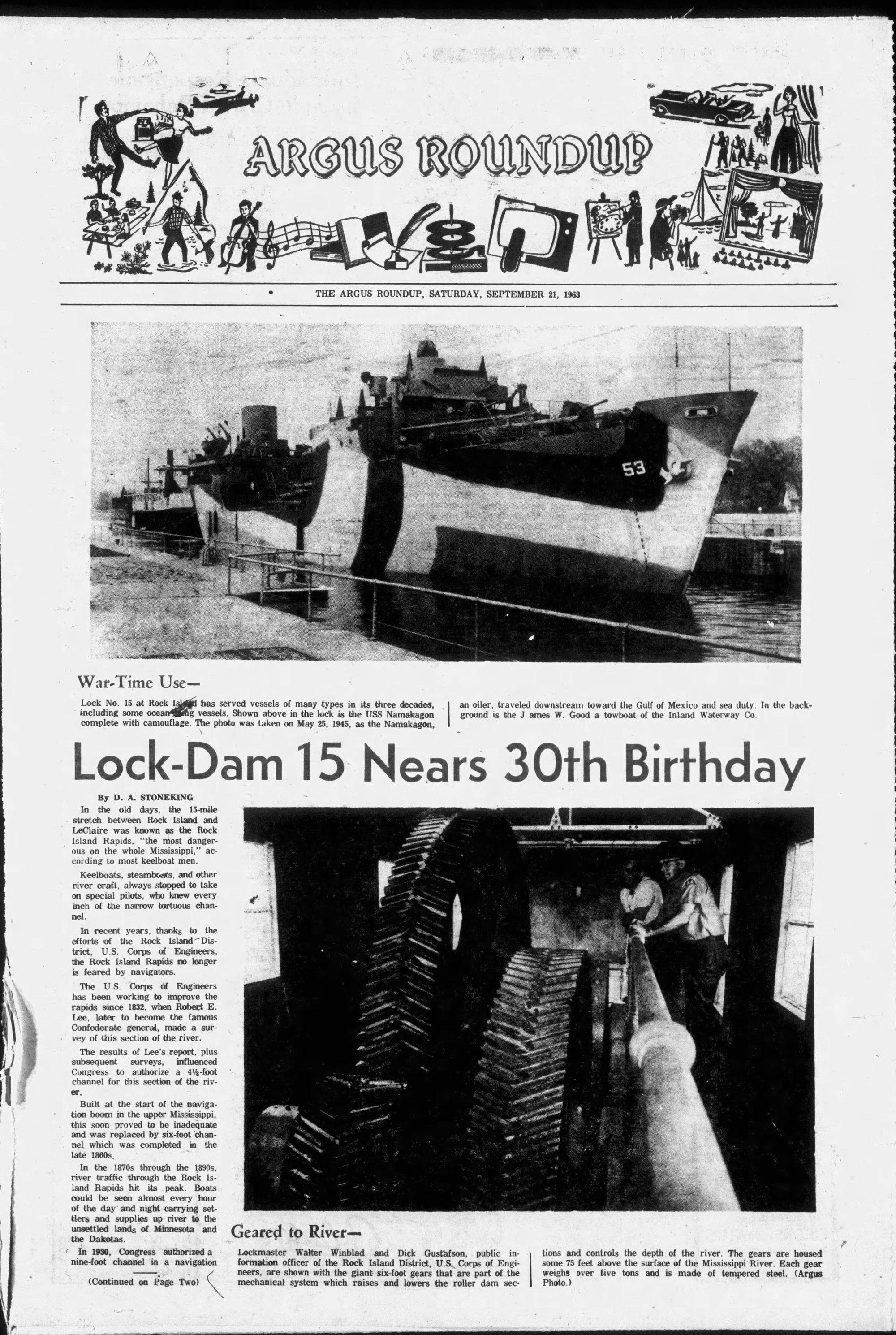

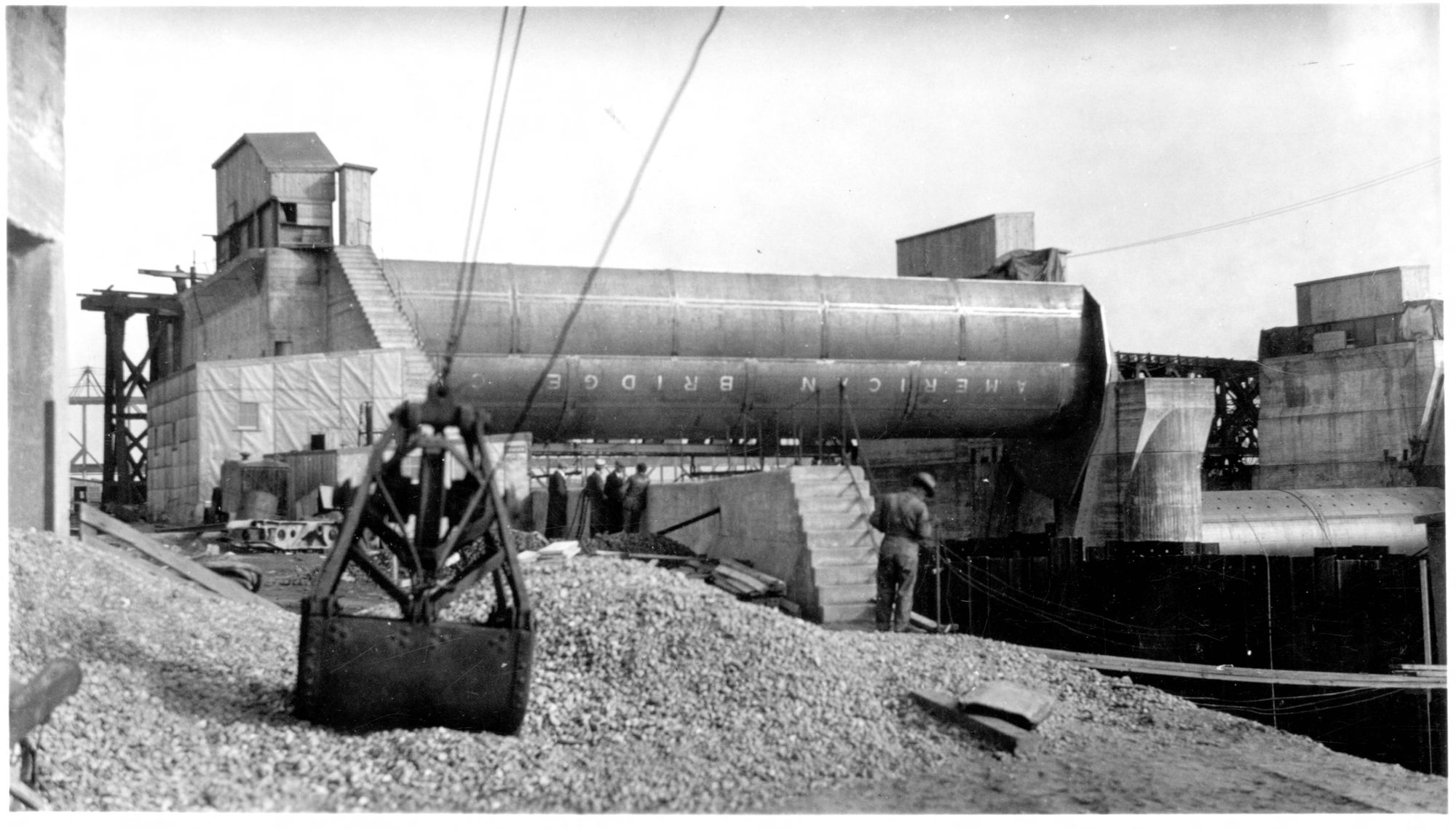

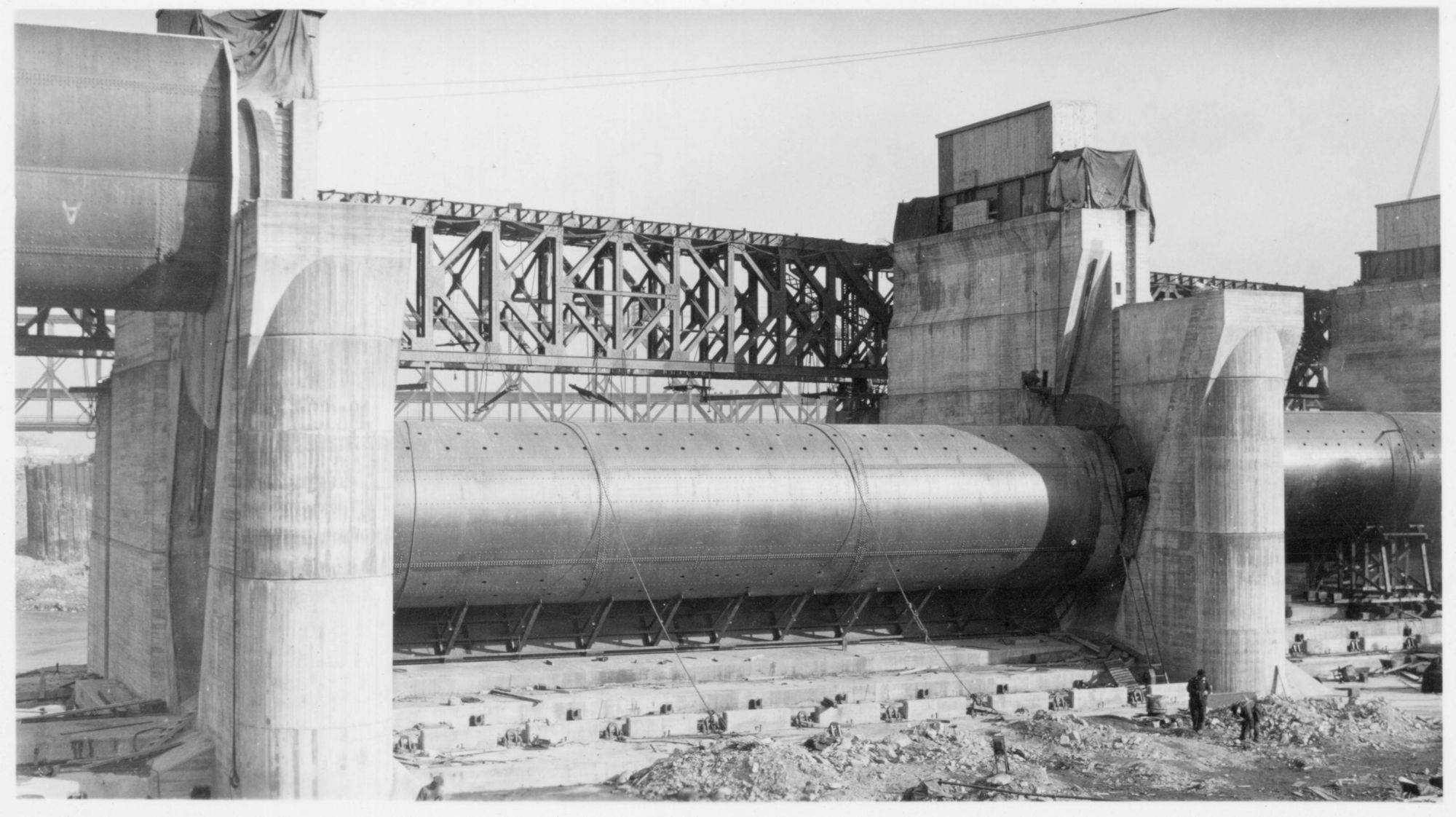

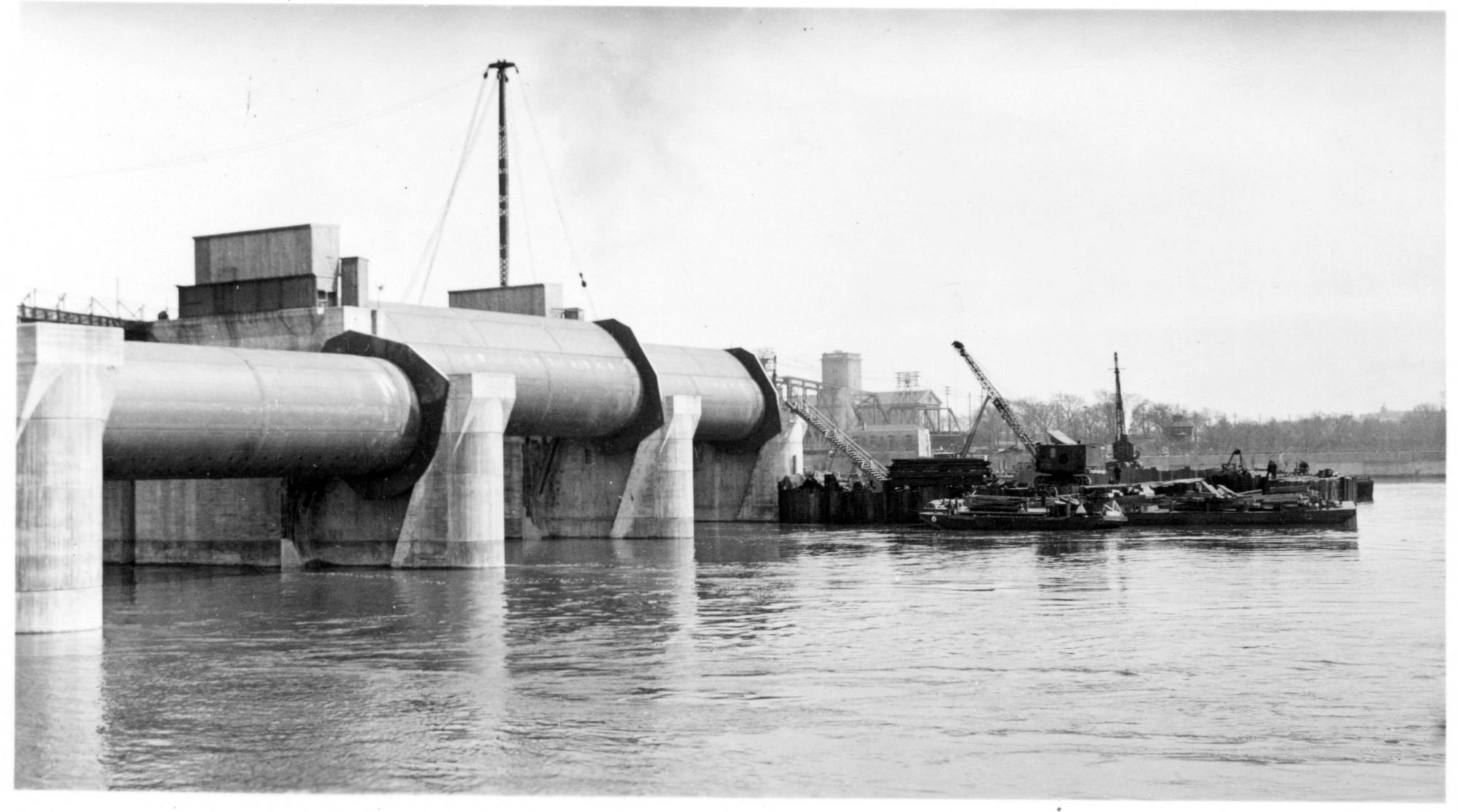

Narrower than in most of its course, with the once-fearsome Rock Island Rapids upstream, the Mississippi between Davenport and Rock Island sometimes caused problems for river shipping. The 9-foot Channel Navigation Project, authorized by the 1930 Rivers and Harbors Act after a long fight, aimed to tame the river's unpredictability. It compelled the USACE to devise a way to maintain a nine foot channel depth, at low water, with widths suitable for long-haul barge service. Basically, the Army Corps had to build a dam across that narrow stretch of the river to create a reliably deeper pool and submerge the rapids. Led by Head Engineer William McAlpin and, especially, Lenvik Ylvisaker, the USACE built a dam featuring nine roller gates plus two overflow gates that would hold back just enough water to create the upstream “river pool”, providing a consistent navigable channel. Each roller gate has its own pier house with a motor and gears to raise or lower the gate. The other half of the dam is a submerged “sill” that, when the gates are lowered onto it, combines to restrict the river’s flow and fill the river pool upstream. In high water conditions, the gates are raised all the way up and the river flows unencumbered over the concrete sill (but under the roller gates).

The USACE built the lock here before the dam, to ensure continuity of commerce. The dam itself was completed in 1934. Commercial traffic on the Mississippi remains vital today - barges on the river account for almost $600b in economic activity annually and they move an estimated sixty percent of all U.S. grain products. However, the standard Mississippi River barge has outgrown the original 1930s locks - today, fifteen-barge tows, which can haul the equivalent of more than a thous semi-trailers, must in two to traverse the short locks. Taming the river with the 9-foot Channel Project massively disrupted ecosystems, but it’s now also an indispensable route for low-carbon commercial shipping. With that in mind, the Biden Administration's Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 allocated $830m to the USACE to modernize these dams and locks. Lock and Dam No. 15 was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004, and I don't expect the Depression Deco pier houses to change much, but it will be interesting to follow how the Army Corps modernizes the system.

Production Files

Other reading:

- NRHP Registration Form

- Two Mississippi (two-mississippi.com)

- Is the Mississippi River Ready for Climate Change? - Belt Magazine

- Pool-Level Drawdowns: Modernizing Lock and Dam Operations | TNC (nature.org)

- Roller Dam & Locks » RIPS (rockislandpreservation.org)

- Industrial History: Flood of 2019: Mississippi Lock and Dam #15, Rock Island, IL (industrialscenery.blogspot.com)

- Gateways to Commerce: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' 9-foot Channel Project on the Upper Mississippi River (nps.gov)

- Off Limits: The little houses atop the dam (qctimes.com)

Member discussion: