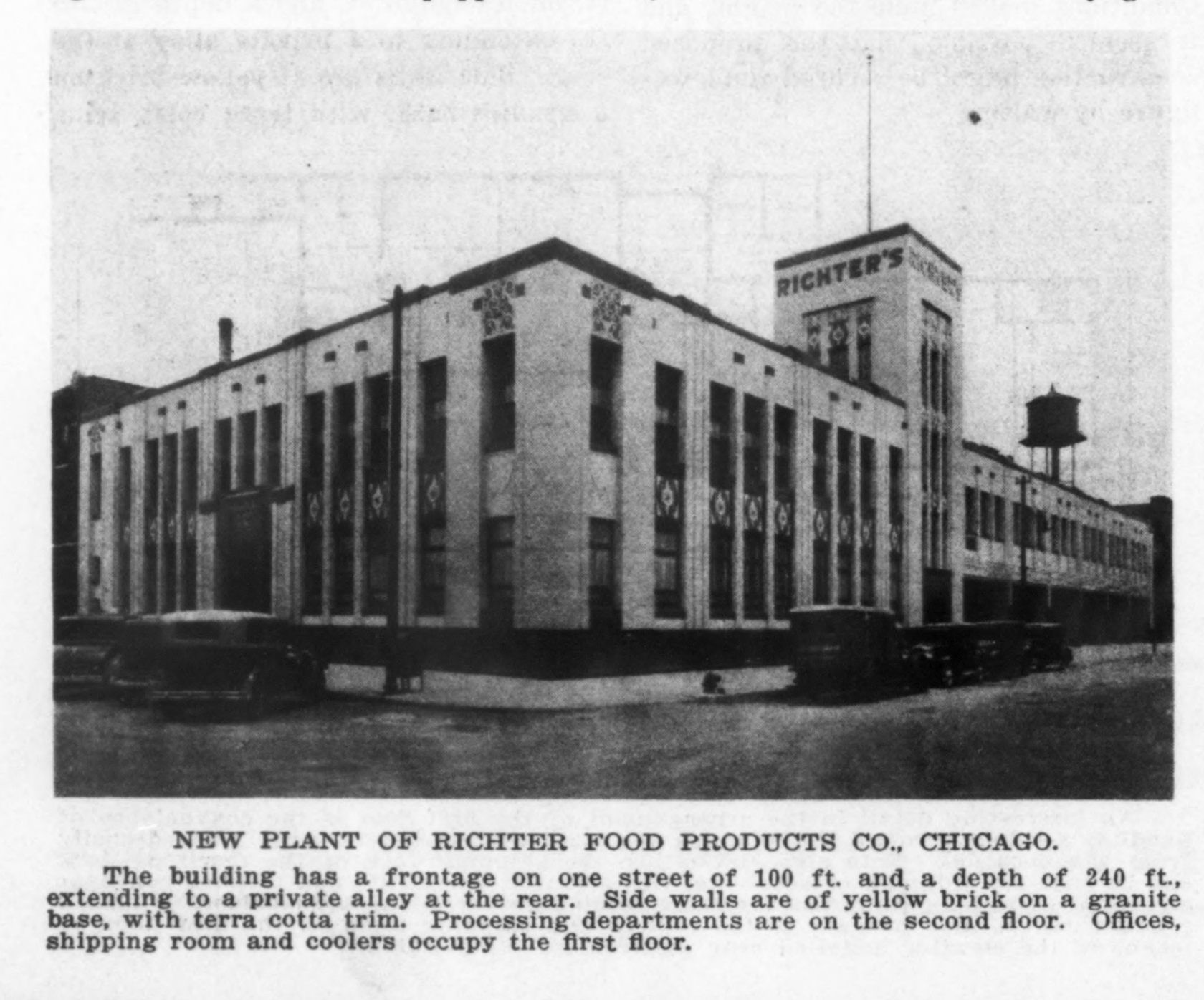

Built as an exuberant Art Deco sausage factory in 1931, the Richter's Food Products Building in West Loop is an illuminating stand-in for the last 90 years of the neighborhood: from meatpacking to a furniture showroom to the one-time headquarters of developer Sterling Bay, who made their name (and a ton of money) defining the modern West Loop. It also parallels the broader trajectory of urban economies, with mass production replaced by real estate and financialization.

It’s a delightful building and the colorful terracotta is a joy. The only major change is the shipping bays, which were filled in at some point (...and the missing chimney, if you consider that major. Given that its removal likely stems from the changing programming of the building, I guess that should count). But the biggest difference is the neighborhood around it–it's now an example of old Fulton Market ringed by the new. Larger neighbors sprouted up around the building over the last five years or so (a growth, again, partially masterminded from Sterling Bay's office within the Richter's Building itself). Both of those larger neighbors epitomize the new Fulton Market style–a brick faux warehouse on the bottom with glass layers on top. On the right, in 210 North Carpenter, a handsome version of it, designed by SCB and developed by Sterling Bay. On the left, Aberdeen East, a fine version of it, designed by Hartshorne Plunkard.

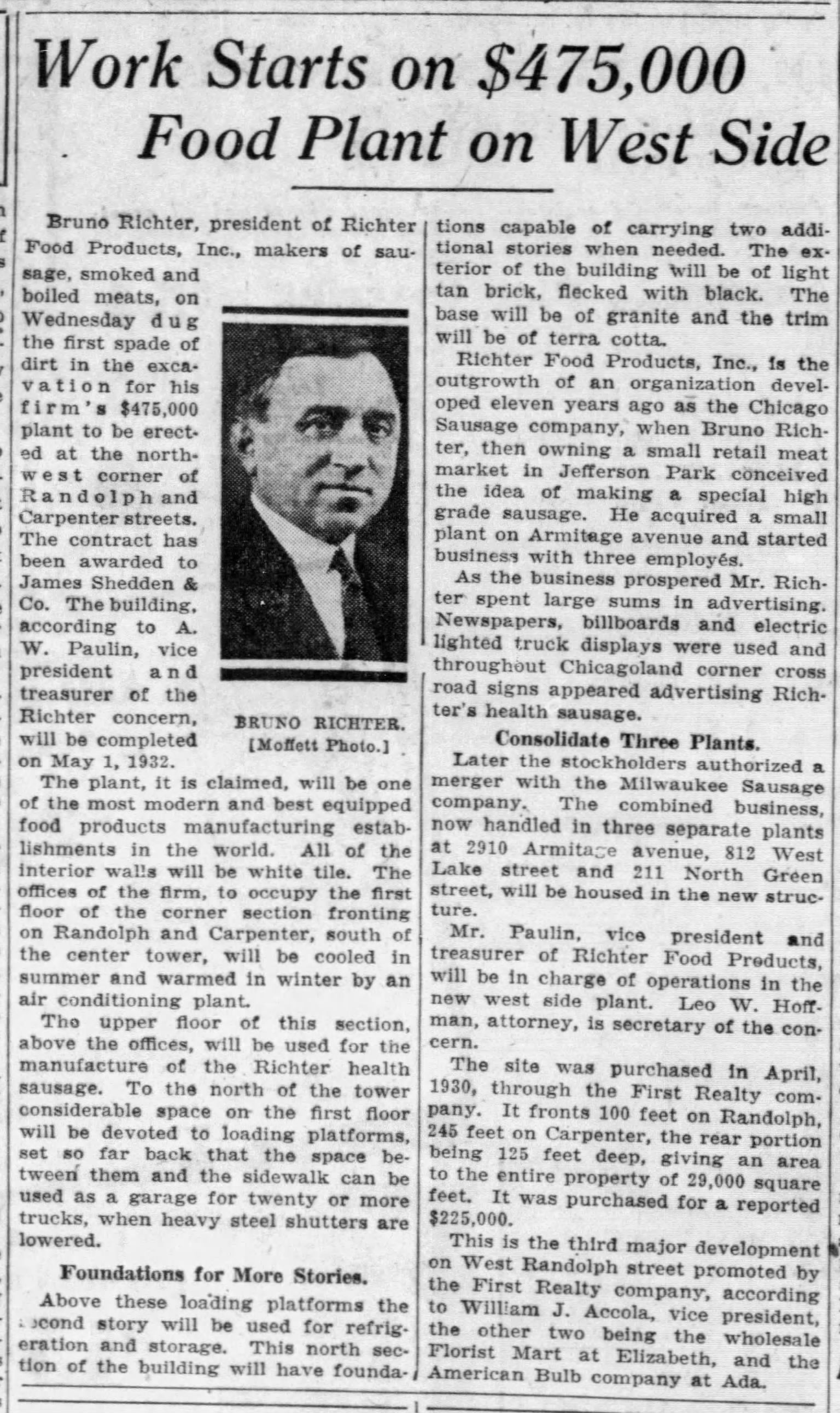

Richter's Food Products was created in 1930, when Bruno Richter's Chicago Sausage Co. merged with the Milwaukee Sausage Co. (confusingly, also of Chicago). Even in the deepest throes of the Great Depression, Chicagoans wanted their hot dogs, so the combined company needed a much larger meatpacking plant. The city had widened this section of Randolph in 1923 to accommodate produce dealers displaced by the closure of the original South Water Market downtown, and Fulton Market was already home to a clutch of independent meatpackers–it was a natural place for a growing sausage company to land.

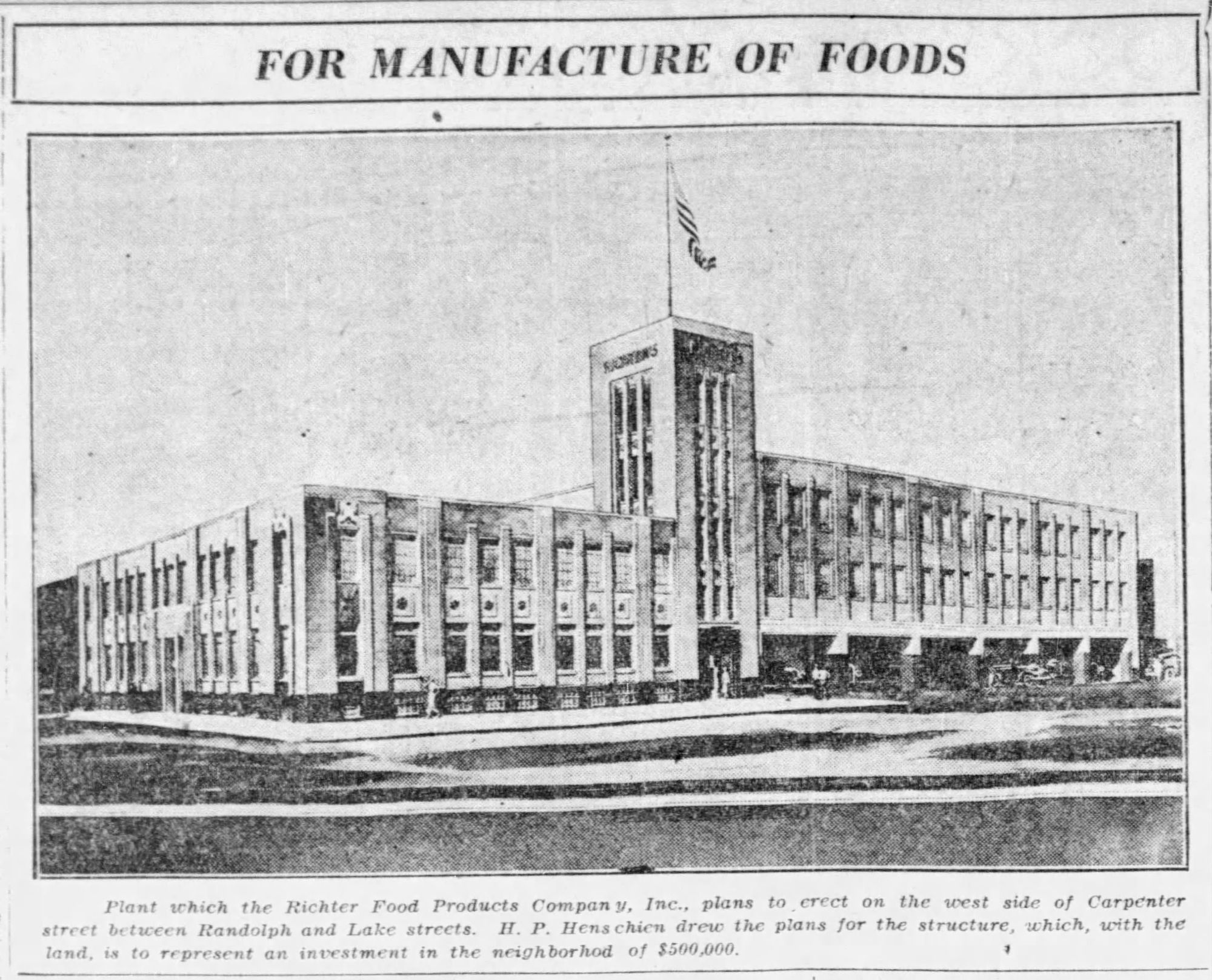

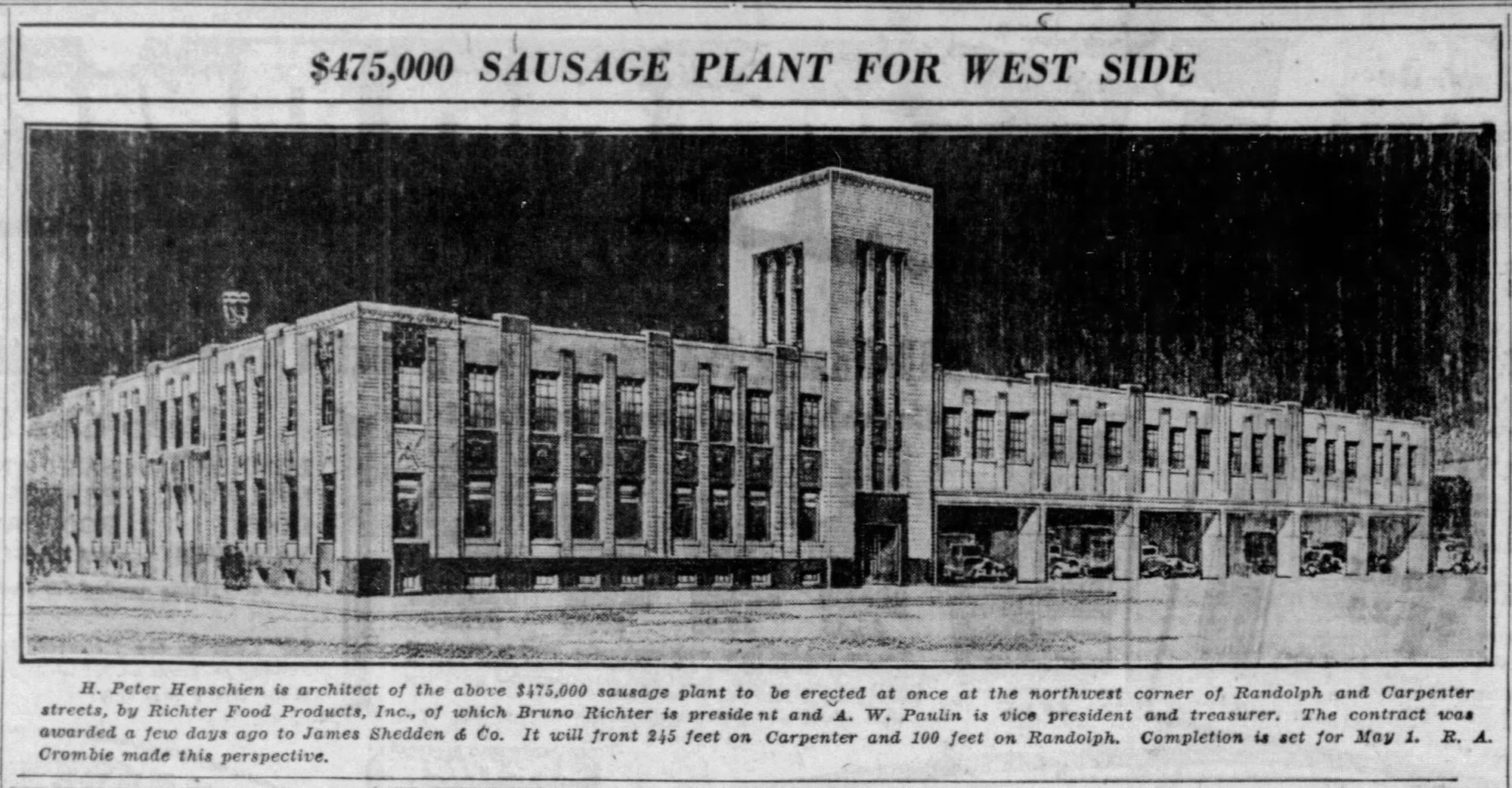

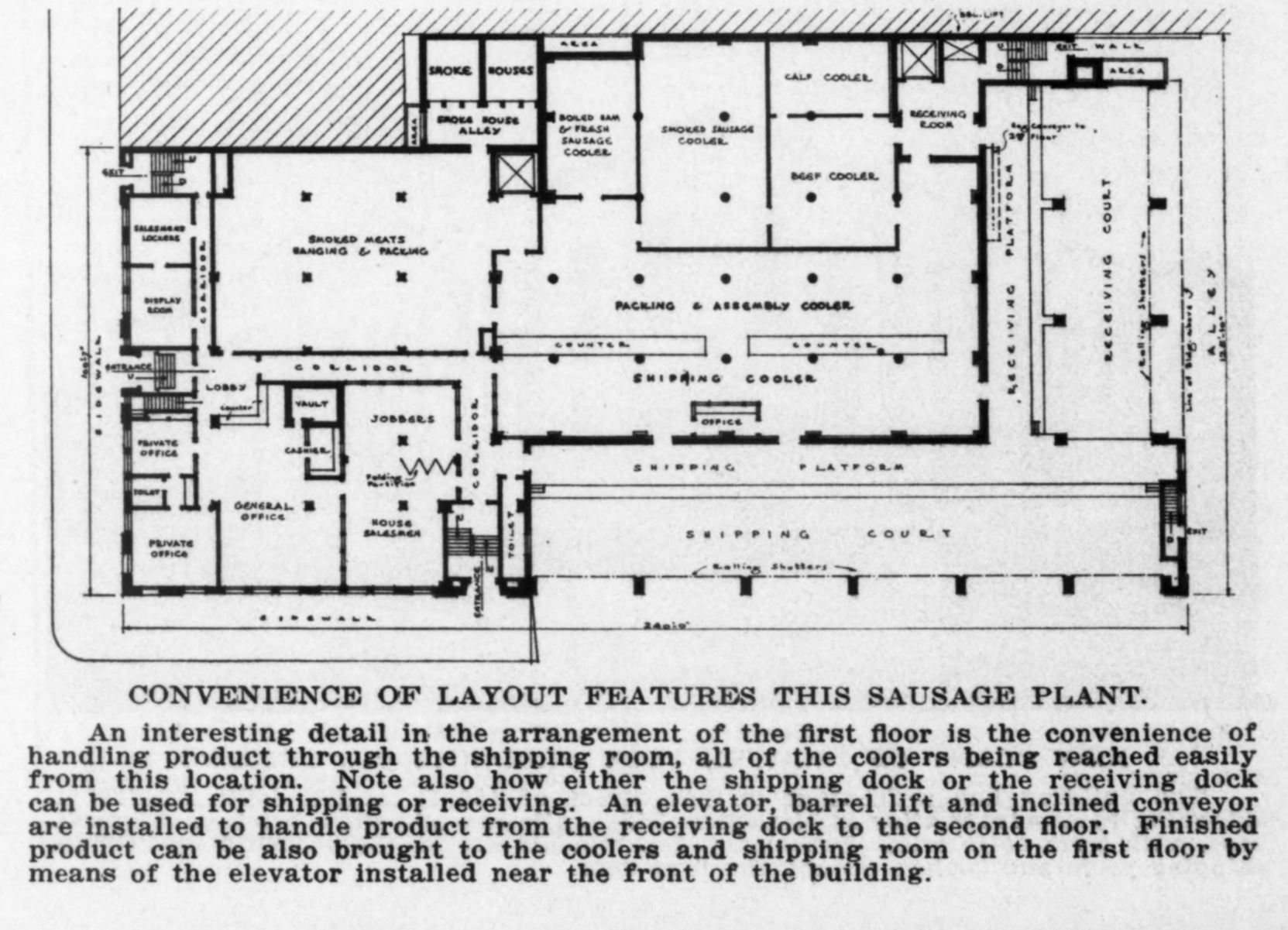

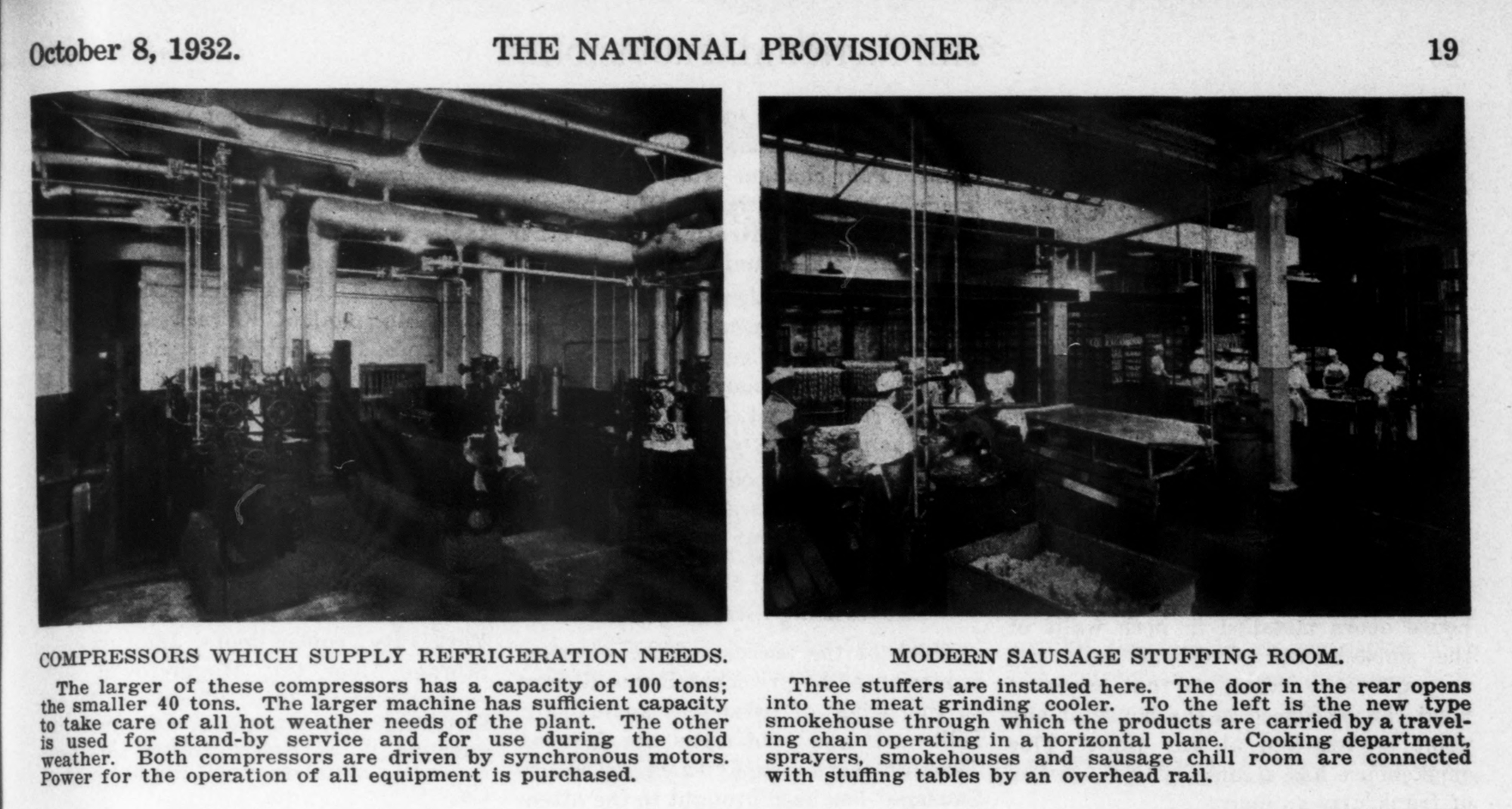

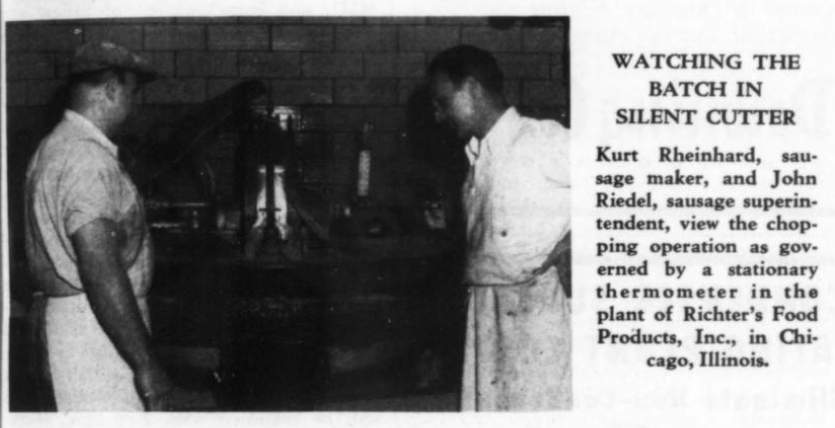

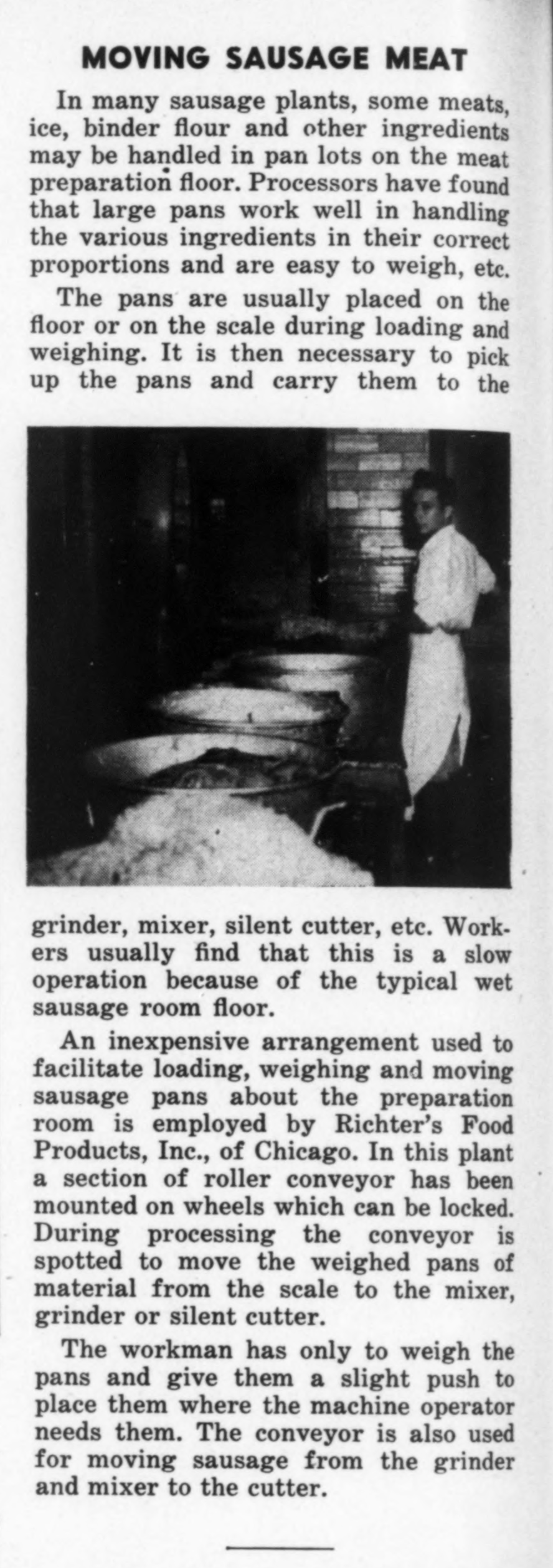

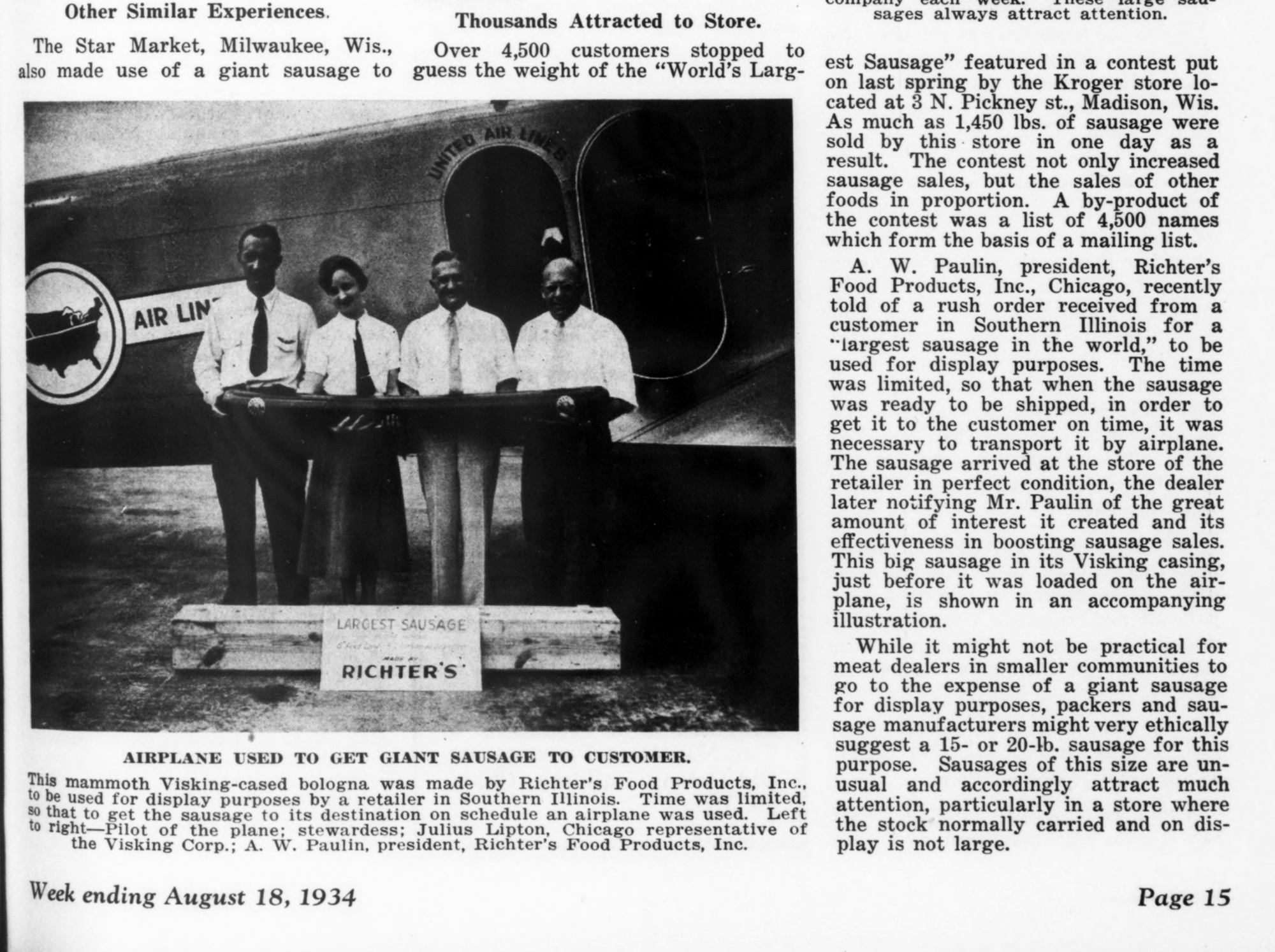

To build their new plant, Richter's hired the guy who literally wrote the book on designing meatpacking facilities, Hans Peter Henschien. His Packing House and Cold Storage Construction was published in 1915, and Henschien's firm went on to design more than 300 meatpacking plants. Conceived as a "rational factory" designed for efficient assembly lines, Henschien's plants were cleaner, safer, and cheaper–an affordability mostly achieved by breaking production into its constituent repetitive tasks, which de-skilled the labor and depressed wages. They also designed this building with future expansion in mind–the northern section was built with a foundation to support two additional stories.

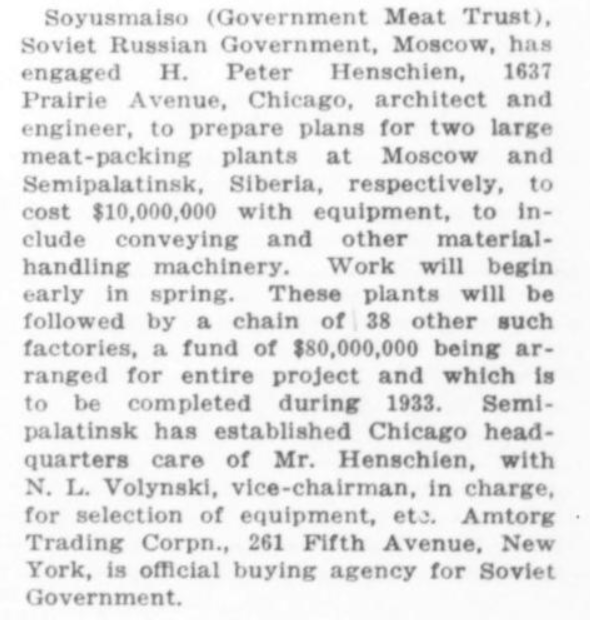

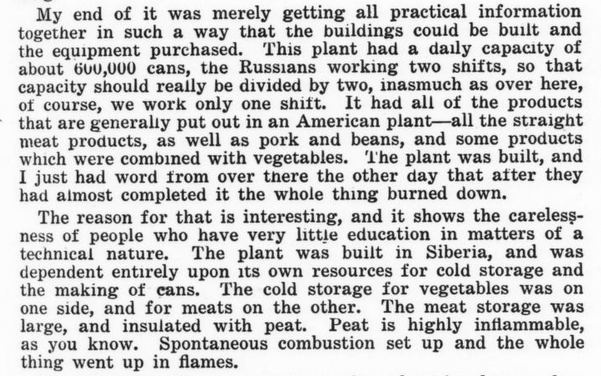

While working on the Richter's plant, Henschien's firm was also working on a very different kind of job. In 1930, a rapidly industrializing Soviet Union commissioned them to design two modern meatpacking plants in the U.S.S.R. Soyuzmyaso, the Soviet meat industry collective, hired Henschien to design US-style meatpacking plants in Moscow and Semipalatinsk (now known as Semey, in present-day Kazakhstan). I expected the Moscow one to be long demolished, but I thought there was a small chance an oddball Constructivist cousin to the Richter's Building still standing in Kazakhstan. Nope–that plant burned down shortly before it was finished.

There's a sick irony to the whole misadventure–at the same time Soyuzmyaso was fumbling around with an experimental modern meatpacking plant in Semipalatinsk, the Soviet Union was inflicting a man-made famine on the Kazakh A.S.S.R. Less well known than the other man-made Soviet famine in the 1930s–the Holodmor in Ukraine–at least 1.5m people died in Kazakhstan between 1930 and 1933, as the state imposed agricultural collectivization and forced sedentarization on a society of semi-nomadic pastoral herders.

Back in Chicago, Richter's Food Products survived until 1951, when they were acquired by another meatpacker, M. Rothschild & Sons. From the 1960s on, a parade of companies passed through the building, mirroring the broader evolution of the neighborhood: Lake Packing meat packers, some very generic-sounding distribution companies, and the Gallery 1040 furniture showroom. From 2008 until 2011 it was the headquarters of First Chicago Bank & Trust, a local bank created from the merger of Labe Bank and Bloomingdale Bank & Trust in 2006. Highly exposed to commercial real estate, the bank took a beating during the Global Financial Crisis and Great Recession. First Chicago failed in 2011, with Wintrust Bank taking over its assets.

Sterling Bay, the developer that arguably shaped West Loop more than any other over the last decade, moved in in 2012, buying the building for $4.7m. It was included as a contributing building in 2015 when the city designated the Fulton-Randolph Market Landmark District, which should protect it from demolition. Sterling Bay flipped the building for $33m in 2019 to Henry Crown & Company. TAG - The Aspen Group, a dental and healthcare company who relocated their HQ to Chicago from New York in 2020, recently opened the TAG Oral Care Center for Excellence in the building. They will use it as a clinical training center for practitioners, offering no-cost dental care to under-served Chicagoans–from filling sausage casings to filling cavities in 92 years.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Fulton-Randolph Market District Landmark Designation report

- H. Peter Henschien, Packing House and Cold Storage Construction

- A five page spread about the building in The National Provisioner in 1932, "Builds New Plant to Cut Operating Costs"

- H. Peter Henschien, "Plan Well Before Building", in the National Provisioner, January, 1952

- A little bit about Henschien's work in the Soviet Union in the early 1930s, "Lessons from the Building of a Great Russian Cannery" in The Canning Trade in 1933 and "American Technology and Soviet Agricultural Development, 1924-1933" by Dana G. Dalrymple, 1966

- "Sterling Bay buys Art Deco building on West Randolph" in 2012 and then sells it in 2019, "It stays in the family: Sterling Bay sells Fulton Market building to Crowns for $33M"

- Little bit on the interior build-out for Aspen Dental in 2019 by Skender and Perkins+Will

- Press releases from TAG on the opening of their Oral Care Center of Excellence and it serving its first patients; info on eligibility for the free dental care it provides

- "The Collectivization Famine in Kazakhstan, 1931–1933", Nicollò Pianciola

- Material Loss Review of First Chicago Bank and Trust, the Office of Inspector General of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Member discussion: