The Portland Public Market lasted less than a decade as a market and within 40 years the whole thing was torn down–this building was a boondoggle. An illuminating boondoggle, though, showing how public-private partnerships are often nothing of the sort, just a convoluted way for the wealthy and connected to generate privatized profits and socialized losses. In this case, the private company who built the market went to court to force the city to buy the white elephant they developed, succeeding despite a decade’s worth of corruption allegations, indictments, and a recall election. It also reveals the intense, almost tectonic, pressure it took to reshape American cities in favor of cars–by replacing the old Carroll Public Market with a new, auto-friendly hulk here city planners could redesign Yamhill Street to prioritize cars–but also the fight back for livability, with the demolition of the Market Building and Harbor Drive in the 1970s the first example of freeway removal in the US.

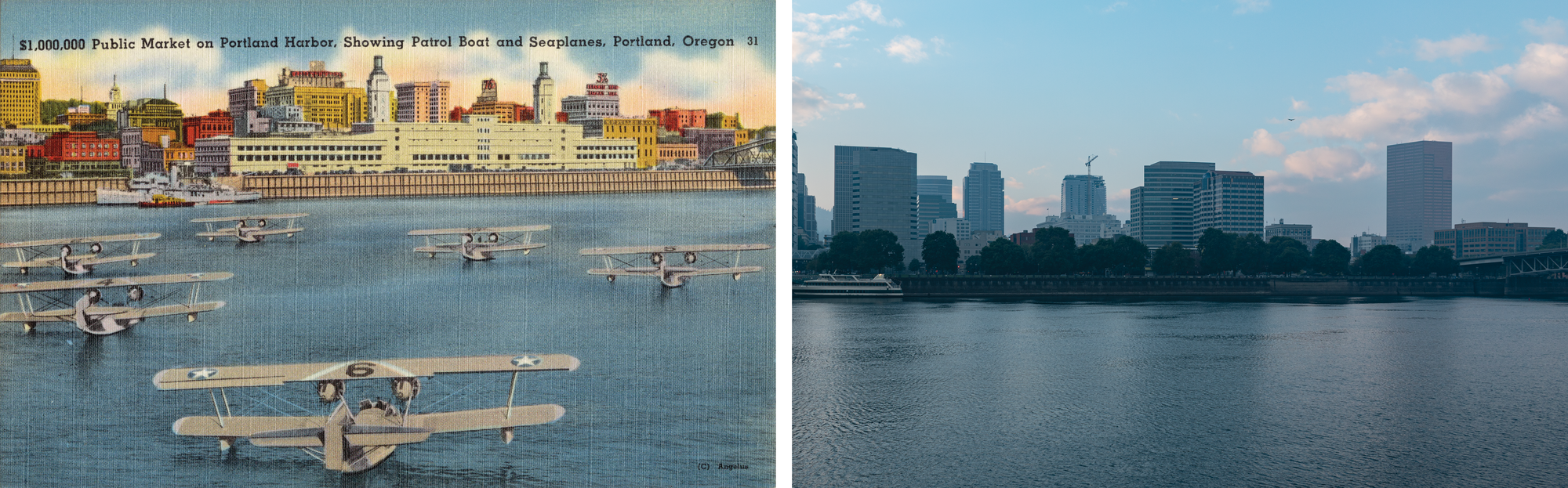

So what, uh, hasn’t changed? It’s been a big ~90 years for Portland’s Willamette riverfront and while broadly recognizable in form–seawall, bridge, and buildings set back–you can barely pick out anything remaining from the postcard. Even the Morrison Bridge has since been replaced. That said, there are still a few survivors peeking through–I spot the Spalding Building, the Yeon Building, and the Meier & Frank Building.

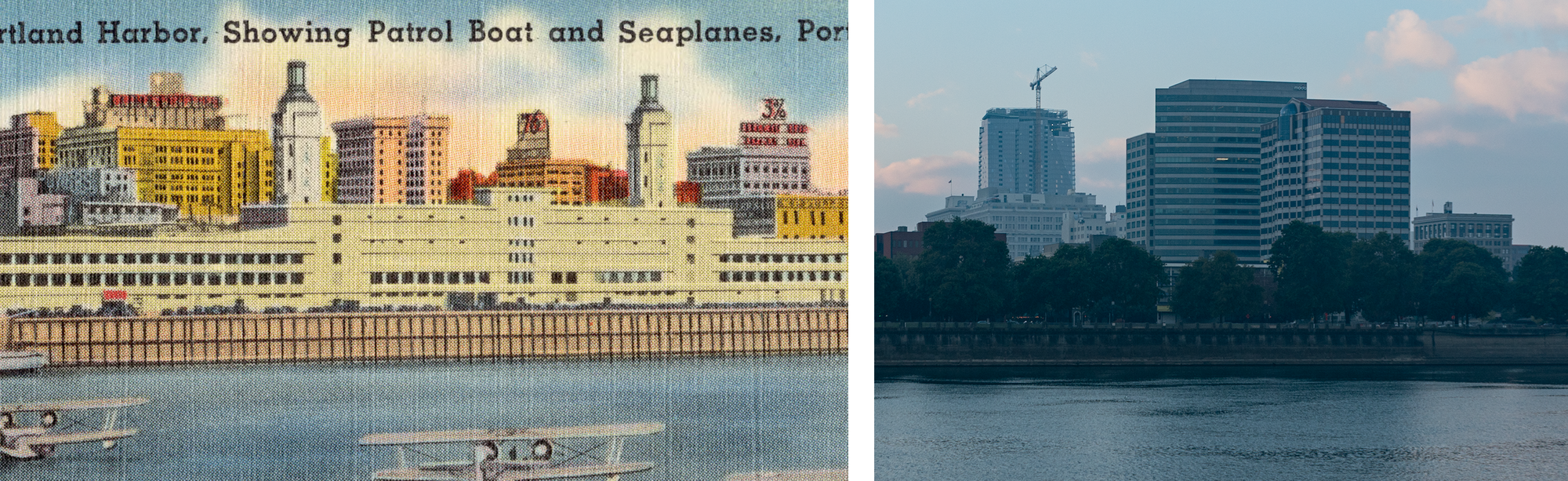

1923 photo of a newstand with a produce stall at the Carroll Public Market in the background, Portland Public Works Administration | 1925 photo of a stand selling razor clams from a stall on Yamhill Street, Portland Public Works Administration

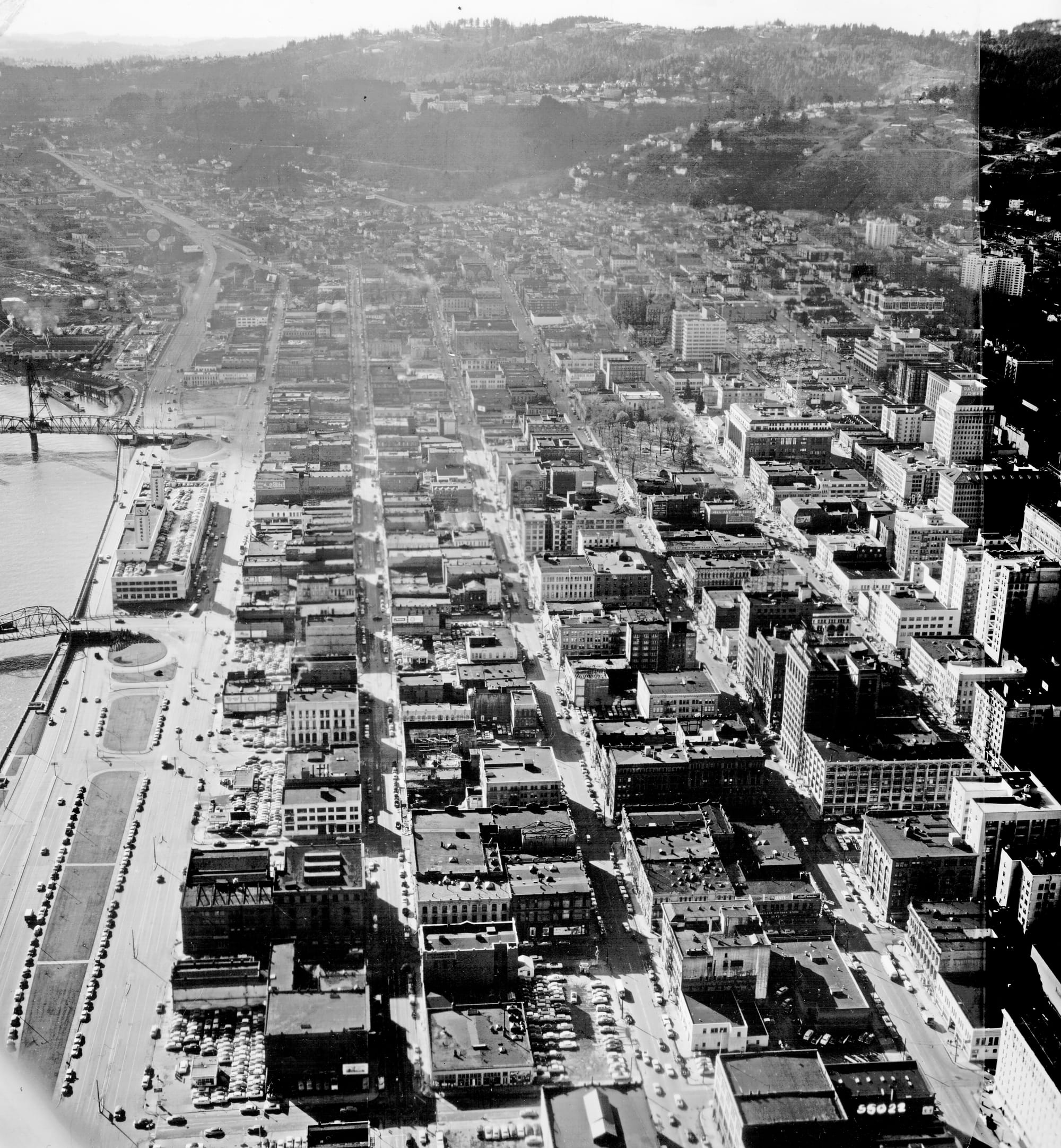

One of the original sins of the Portland Public Market was that the city already had a popular market, the curbside Carroll Public Market, which ran along Yamhill Street from First Avenue to Fifth Avenue. Popular with farmers and consumers, Carroll Public Market was lively, decentralized, and had expanded and organized relatively organically. Unlike its eventual successor, it was also quite profitable. However, profitability and popularity weren’t enough–city planners considered it an obstacle to the efficient movement of cars, and its self-organized bustle clashed with their conceptions of what was appropriate for a “modern” city.

Plus, a bunch of wealthy and connected landowners owned property down by the river–property whose value would increase with proximity to a successful, modern new market. By replacing the ground-up Yamhill Street Market with a top-down centralized market on the riverfront, the riverfront landowners could cash in and the city could reconfigure Yamhill to prioritize car traffic. Those wealthy and connected landowners formed the Portland Market Company to build a new riverfront market, with the promise that the city would buy it upon completion. About as shady as it sounds–a bunch of politicians were indicted for taking bribes in connection with the project, including Mayor George Baker, who also narrowly survived a recall election sparked by the fiasco.

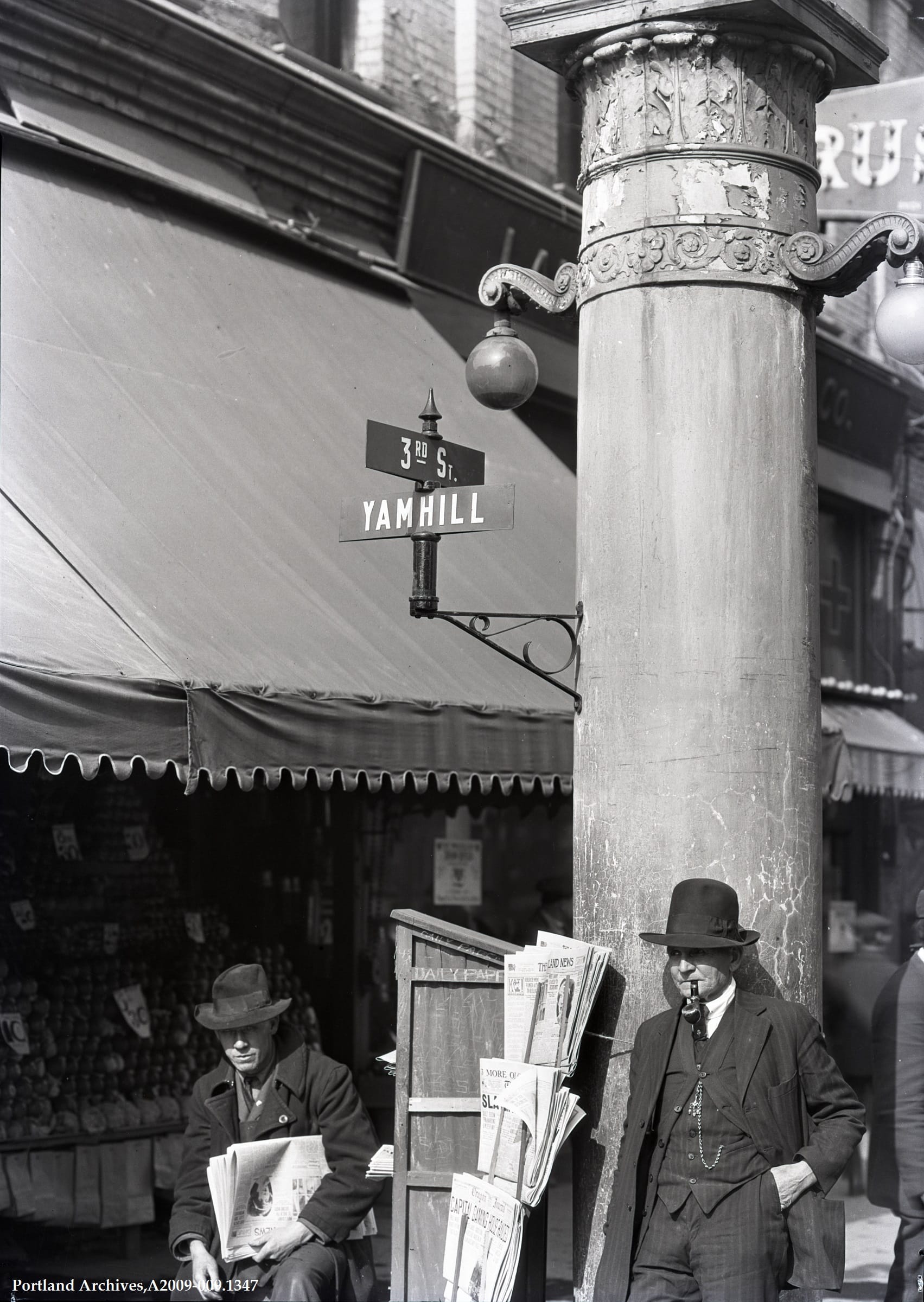

1931 article and sketch on the plans for the new public market, the Engineering News, the Internet Archive | 1933 article on the groundbreaking

After funding stalled with the onset of the Great Depression, the city secured the project a loan from the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation, a New Deal-era government agency whose remit FDR expanded to finance agriculture, infrastructure, and housing projects to stimulate employment. Opposed by its future tenants and under a cloud of corruption and economic malaise, construction on the mammoth new Portland Public Market finally began in 1933. Leveraging the enormous workforce idled by the Depression, it opened after just five months, in December of that year.

Featured in an Portland Cement Association ad in 1935 in Architectural Record, the Internet Archive | 1936 photo, Arthur Rothstein, the Library of Congress | 1934 article on the Portland Public Market, Electrical West, the Internet Archive | undated postcard | 1935 aerial, City of Portland Archives | 1941, Portland Public Works Administration |

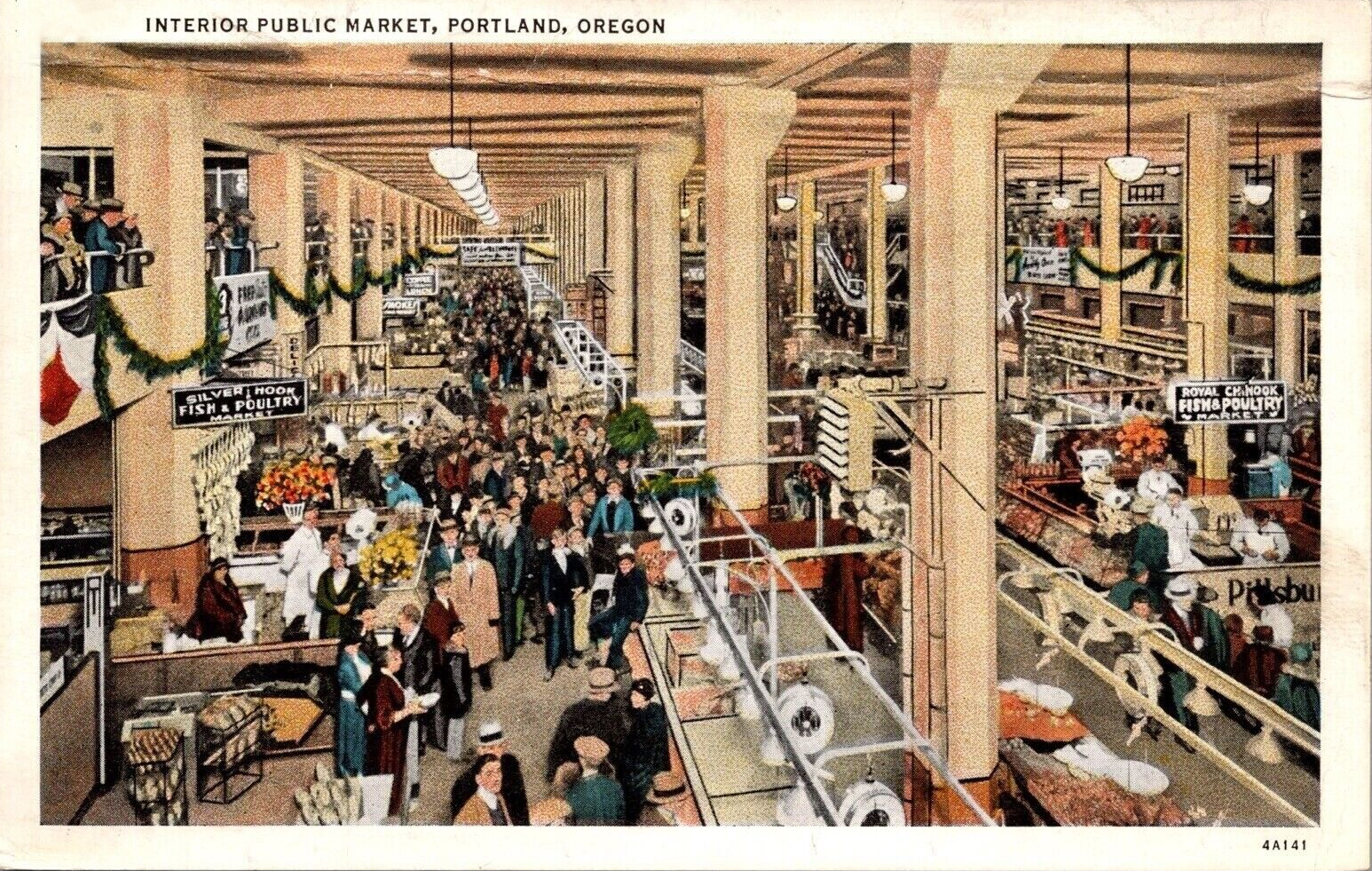

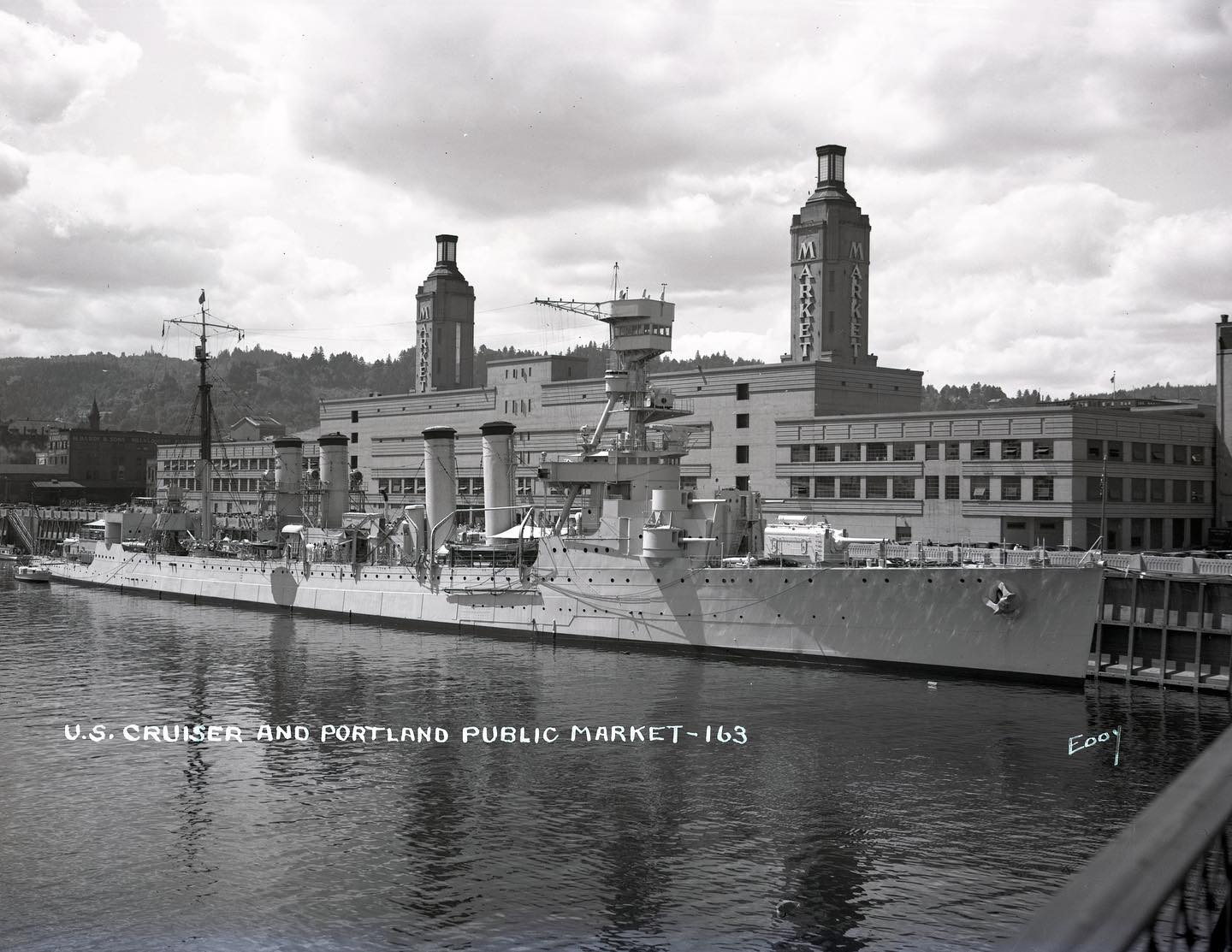

Designed in a utilitarian Depression Moderne style by William G. Holford of the Portland firm Lawrence, Holford, & Allyn, the million-dollar market was an auto-oriented shopper’s dream. Sited right next to a highway, with rooftop parking and a gas station, it was clean, sterile, and highly organized.

Interior photo in Electrical West, 1934 | Interior postcard, undated | undated with cruiser, Clackamas County Historical Society | 1954, Portland Public Works Administration

It had all the attributes of a modern public market…and people did not like it. Far from the heart of the city, its isolated location repelled customers and frustrated producers, and it was organized to serve a narrow, idealized customer type–housewives who drove into the city–who didn’t really shop this way (and its centralized structure made adaptation unlikely). The Portland Public Market also had the misfortune of opening during a catastrophic depression–so none of those customers had any money anyway. Splinter groups of vendors stayed on Yamhill Street or quickly abandoned the new market. Any early buzz for the fancy new market faded fast and it never turned a profit.

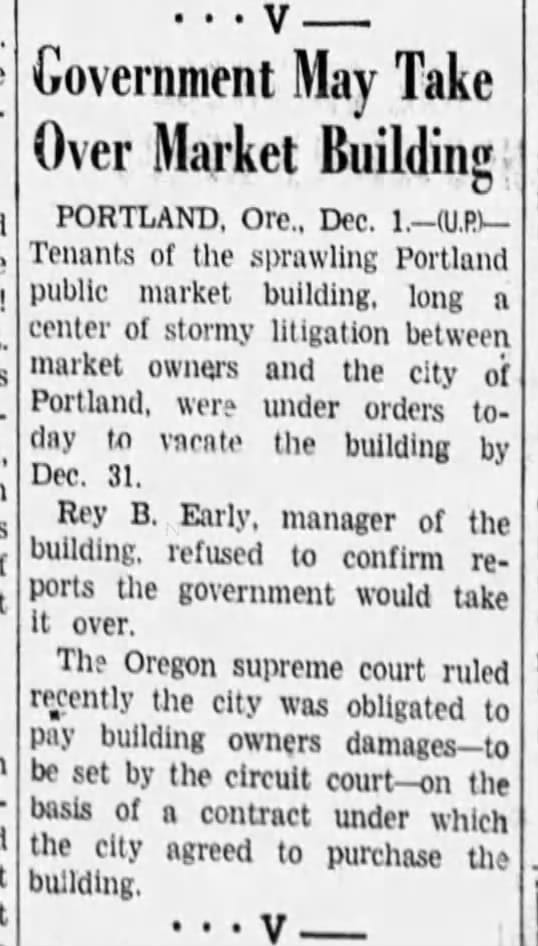

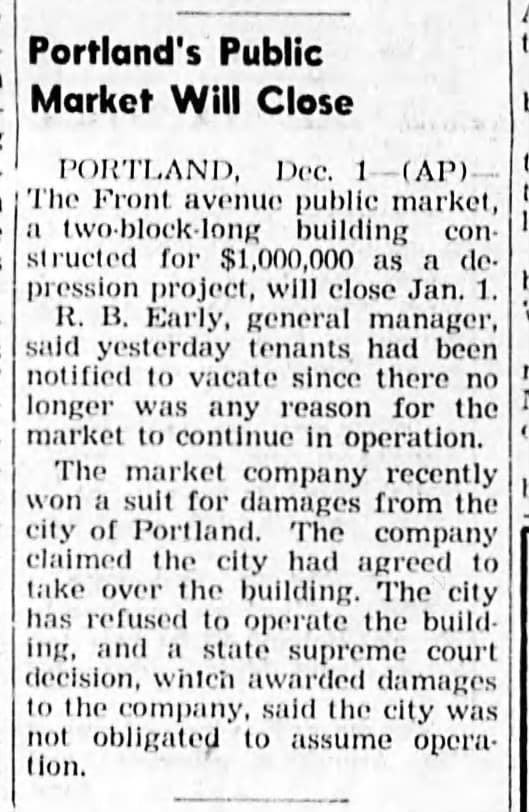

The new mayor and city commission–realizing what a bum deal their crooked predecessors had made–tried to renege on the agreement to buy the market from the Portland Market Company, kicking off nearly a decade of litigation that ended up in front of the Oregon Supreme Court.

1940s article on the legal battle around the Portland Public Market, its closure, and its lease to the Navy

The city lost. Forced to buy out the politically-connected landowners who’d developed the building, after taking ownership of the building in 1942 the city decided to close down the Portland Public Market rather than run a failing operation that no one really cared for. After all that, the Carroll Public Market on Yamhill Street was dismantled in favor of an expensive white elephant that didn’t even last a decade (presumably making some assholes a nice profit on the public ). Emptied of its remaining vendors, the city leased the building out to the Navy in 1943 for use as a riverside warehouse.

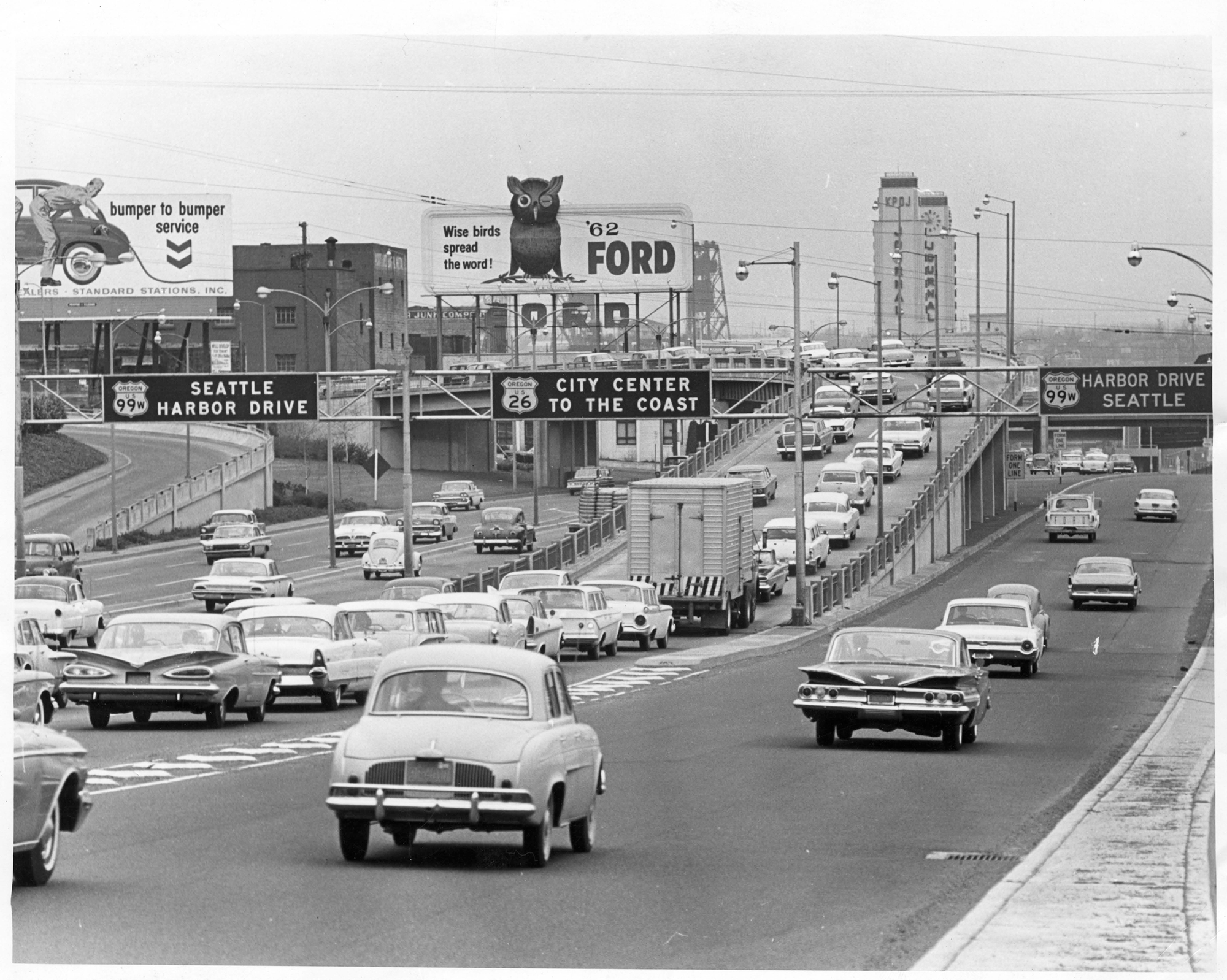

1946 articles on the building's purchase by the Oregon Journal | 1952, dumping snow in the Willamette River, Portland Public Works Administration | late 1950s aerial, Multnomah County Archives | 1962, David Falconer, Portland Public Works Administration

In an interesting twist, the city sold the building to the Oregon Journal, and from 1948 until 1961 it housed the newspaper’s newsroom and printing plant. The Journal peaked the year they moved into this building, and in the 1950s the paper underwent a period of decline under William Knight (Nike-founder Phil Knight’s dad). S.I. Newhouse, the New Yorker who owned the competing Oregonian, bought the Journal in 1961 and consolidated their operations in the Oregonian’s building–not even 20 years later, Portland again had a vacant hulk sitting on the Willamette.

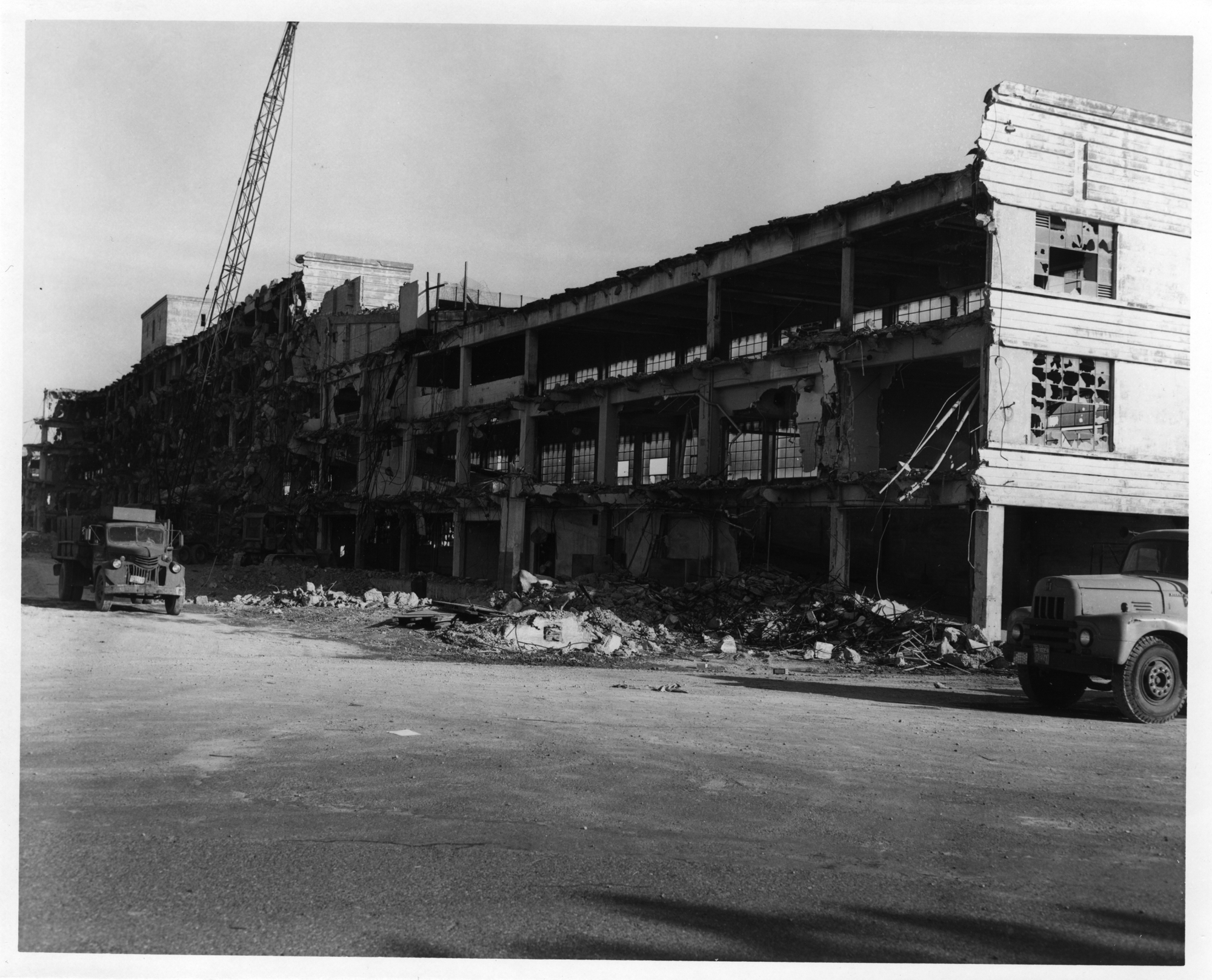

1969, Portland City Archives | 1969, JimD, VintagePortland | 1970, Portland City Archives | 1970 with wrecking ball, Portland City Archives | 1970, Portland City Archives

Writing decades later Carl Abbott said, “that two block mistake…had loomed like a beached whale. It had blighted views, siphoned off money, obstructed waterfront use, and served no useful civic function”. So this time, the city coughed up another $1.6m (~$14m today) to buy and raze it, with demolition beginning in 1969. I’m sure it could have been a neat building if it had survived, but it’s hard to separate the building from the rancid process that created it and its awful context, ribbons of asphalt on the river.

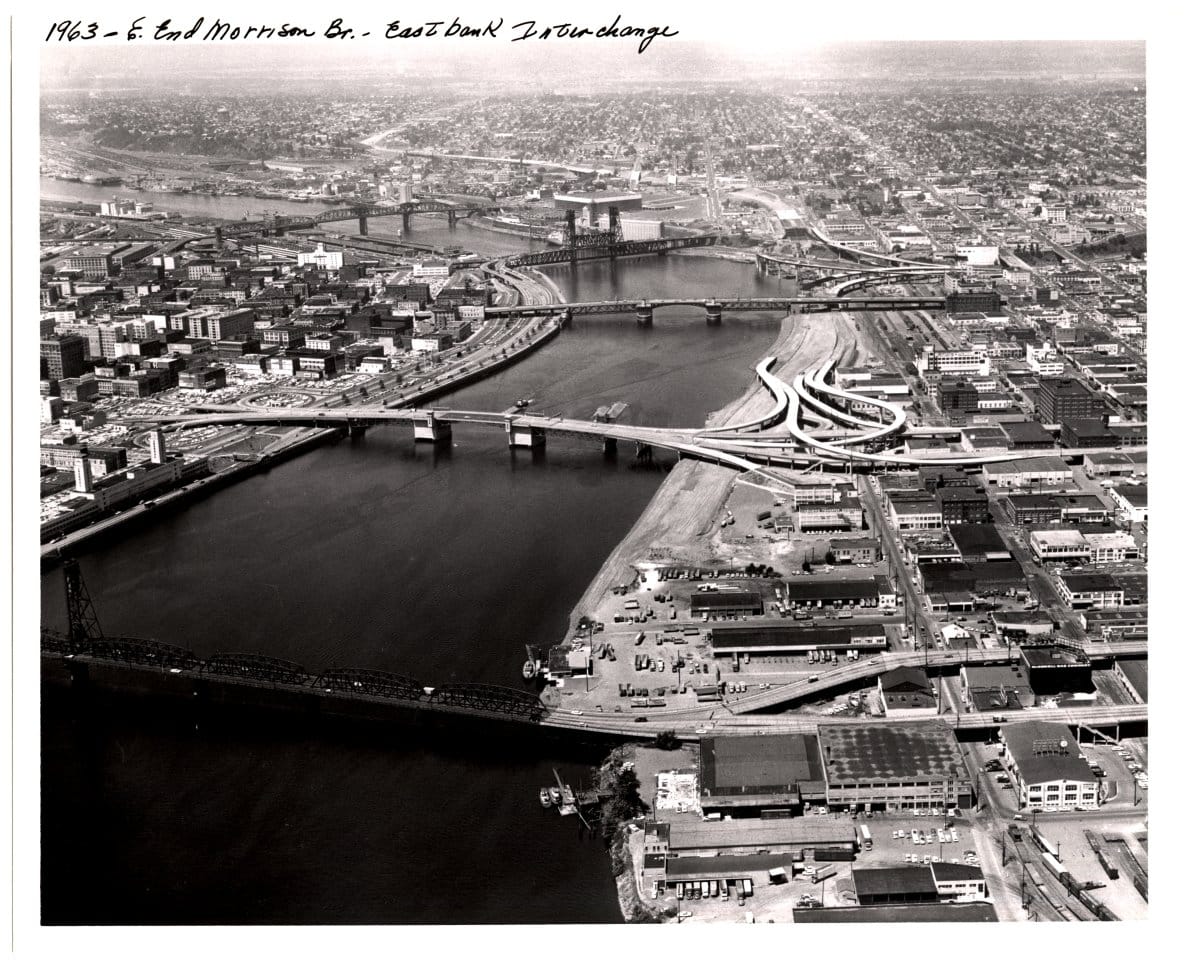

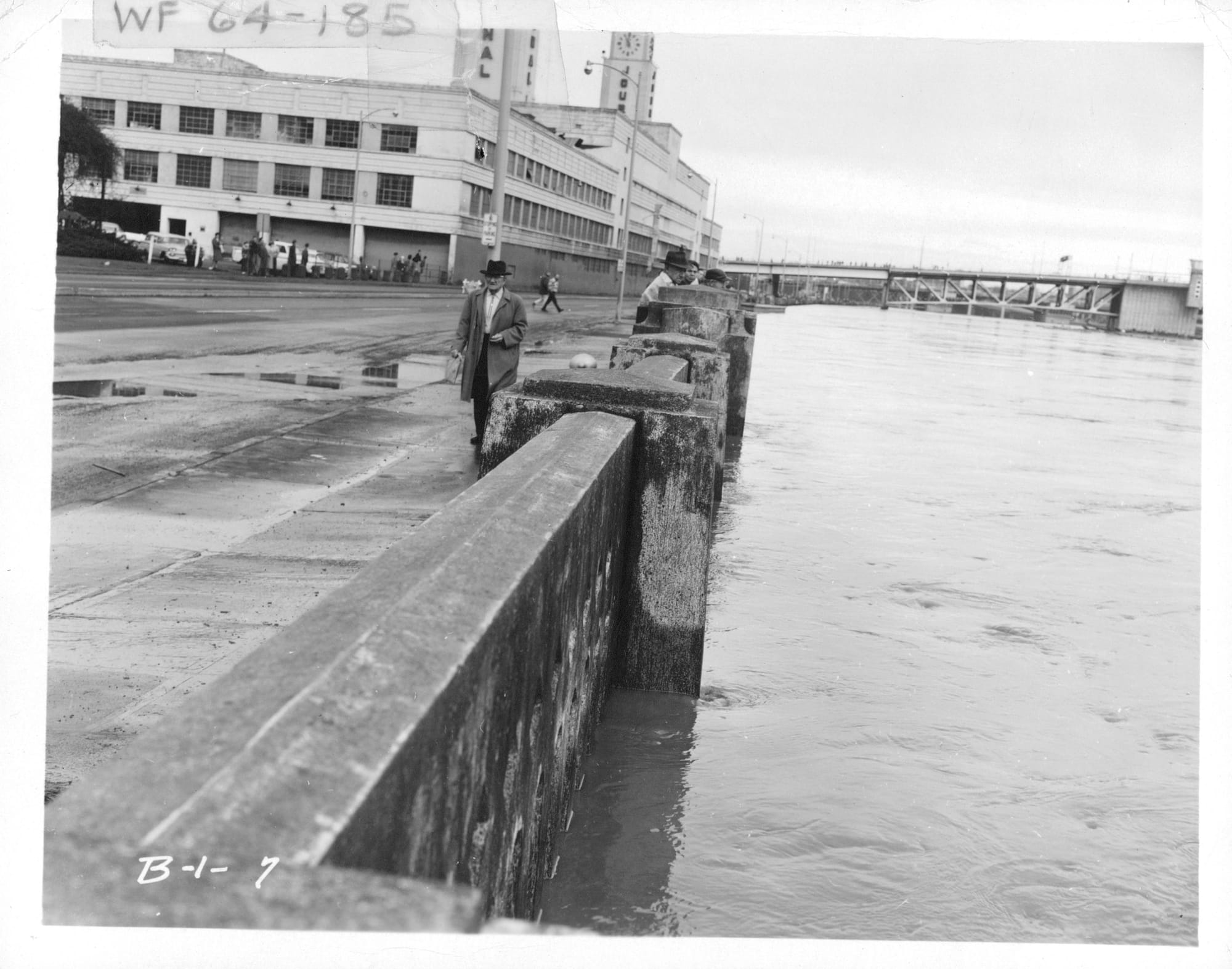

Late 1950s, Multnomah County Archives | 1963, Portland Public Works Administration | 1964, Portland Public Works Administration

The freeway that came to surround the Portland Public Market, Harbor Drive, was the first highway in Portland. Thirty years old by the time the market building was torn down, the aging freeway also cut Portland off from its riverfront, so in the late 1960s Oregon Governor Tom McCall convened the Harbor Drive Parkway Task Force to come up with plans for the future of Harbor Drive (including the site of the demolished market building). Led by the chair of the Oregon State Highway Commission, the task force came up with four predictable options and one outlier: highway expansion, highway expansion (trenched), highway expansion (tunnel), highway expansion (temporary), and…removal.

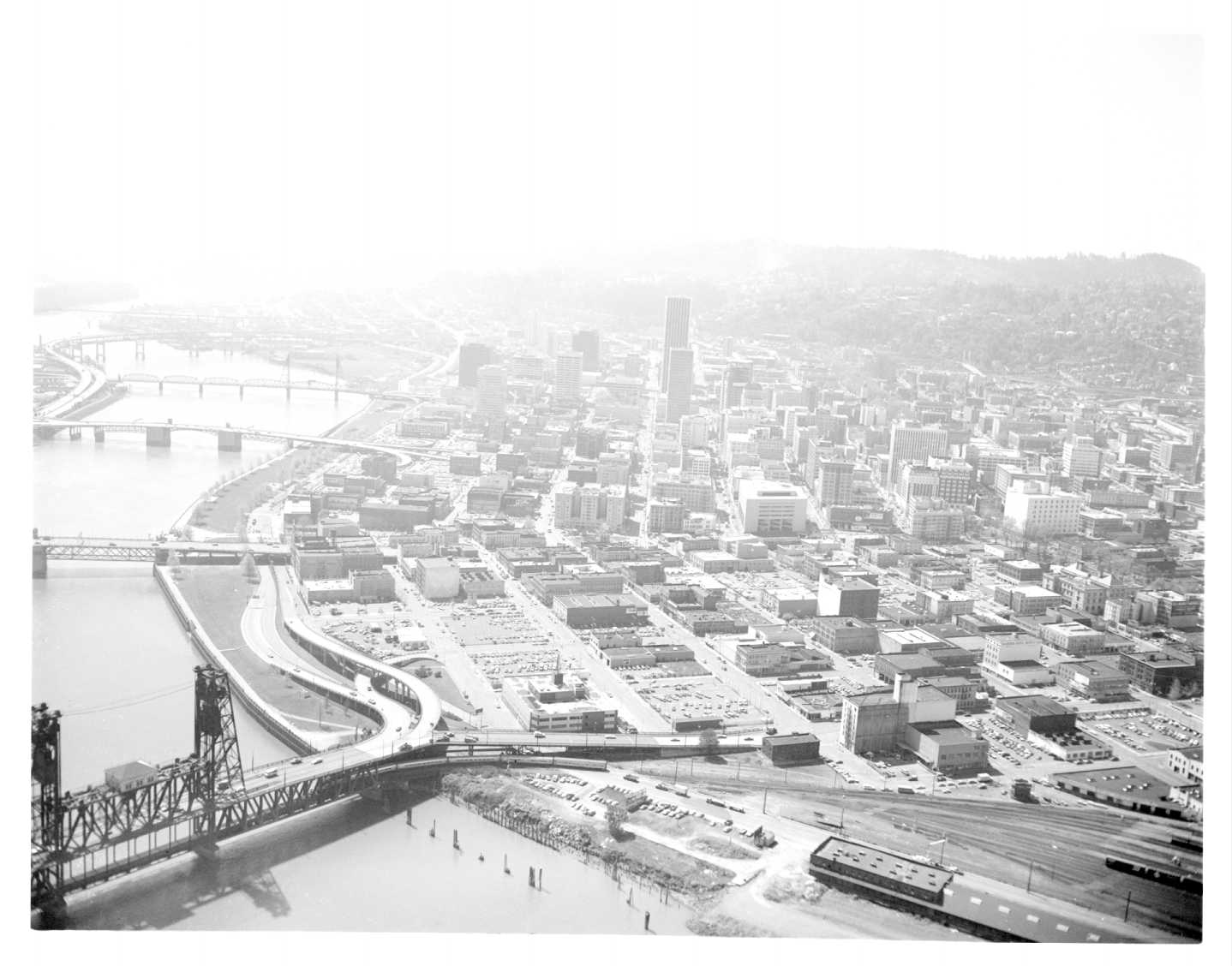

Obviously, removal was off the table for the transportation planners, who were convinced it would cause chaos. Gov. McCall–who seems like he was pretty great–disagreed. It was a years-long process, but after sustained public pressure from activist groups, input from a citizen advisory board, and genuine political courage from the governor, the removal option won. Deconstruction of Harbor Drive began in 1974, reconnecting Portland with the river and recovering the space for the public. Later named for the governor who helped make it happen, the Governor Tom McCall Waterfront Park opened in 1978.

1948 aerial, Portland City Auditor Historical Records | 1979 aerial, Portland Public Works Administration | 2007, Joel Mann, Flickr

There’s an encouraging trajectory here. A car-oriented boondoggle–the unloved creation of a corrupt process conducted to further enrich the wealthy–razed by the state, returned to the public, and rebuilt for people.

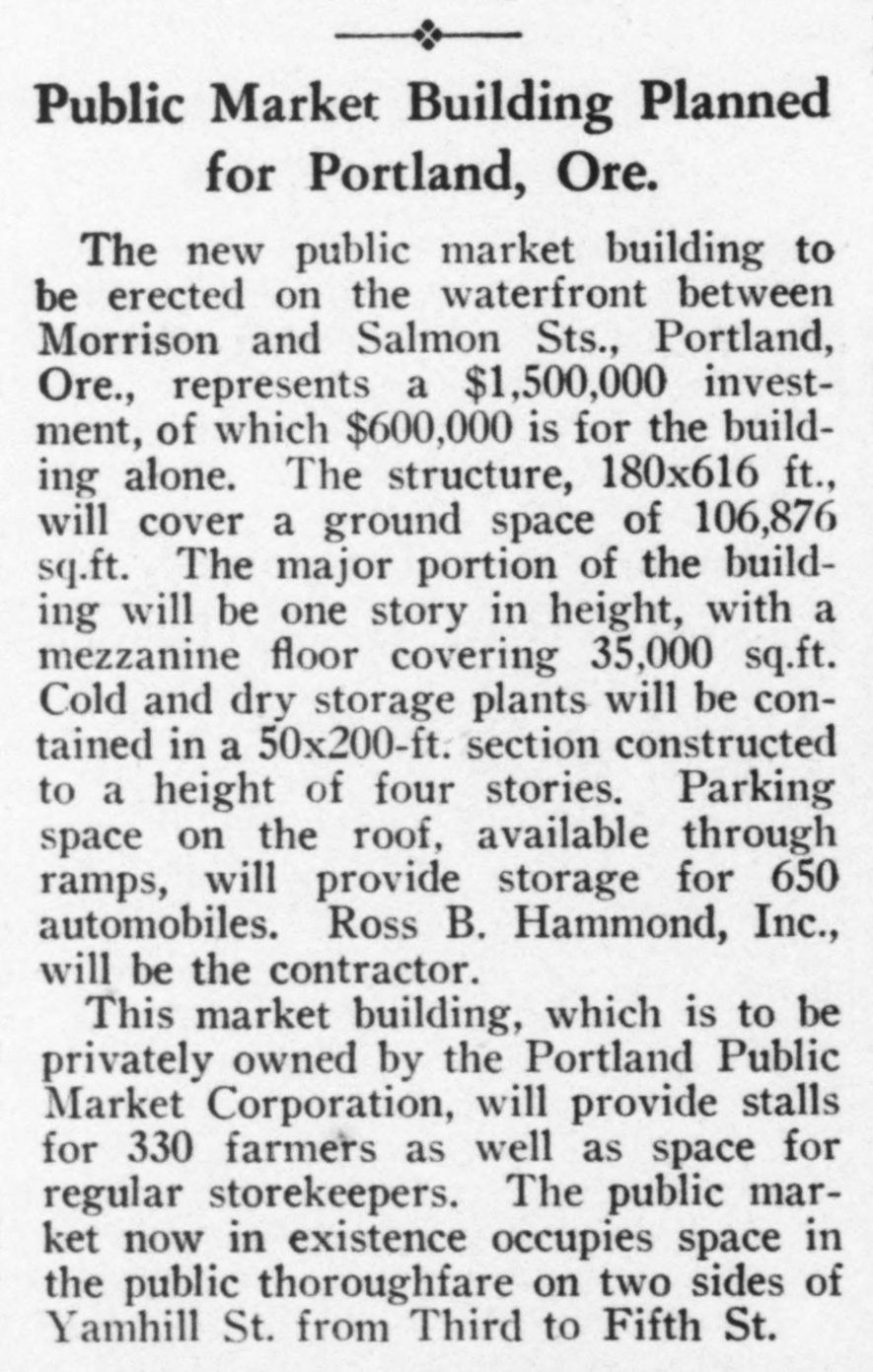

Undated postcard | 2012, Steve Morgan, Wikimedia Commons

Production Files

- Michael Anthony Jenner, "The Origin of Portland, Oregon's Waterfront Park: A Paradigm Shift in City Planning (1967-1978)Paradigm Shift in City Planning (1967-1978)"

- 1969 City Club of Portland Bulletin, "Interim Report on Journal Building Site Use and Riverfront Development"

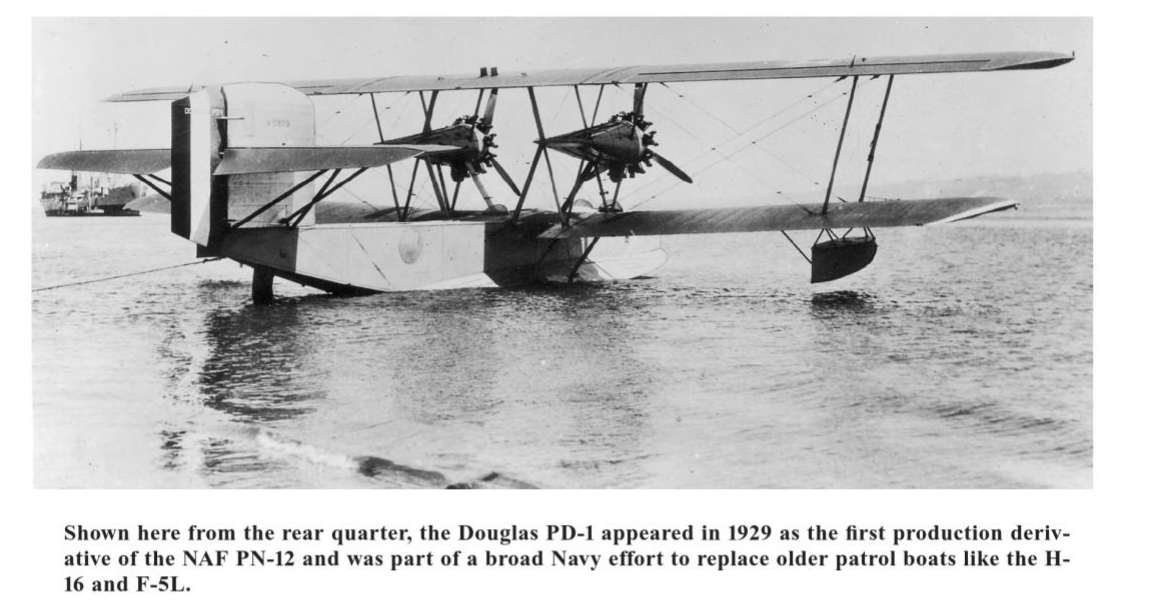

The seaplanes in the postcard are Douglas PD-1s, a variant of the Naval Aircraft Factory PN-12.

PD-1 in postcard | San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives, Flickr

As the city came to grips with the fact that they'd have to take over the Public Market Building, they considered a bunch of options for using the white elephant, including housing and jails.

1964 Christmas Flood, Wikimedia Commons | 1964 Christmas Flood, sandbagging, Wikimedia Commons

Member discussion: