Henry Hefty won the competition to design Portland’s City Hall and construction made it as far as the building foundation before the New City Hall Commission–newly formed by the Oregon state legislature to wrest control of the project away from the city–changed their minds. Citing cost and taste concerns, they dug up the just laid foundation and hired Whidden & Lewis instead. Completed in 1895, the switch meant that Portland ended up with an Italian Renaissance Revival style city hall rather than Hefty’s grandiose Second Empire style one. The building’s pink and gray facade presaged the playful postmodernism that popped up around it over the next century.

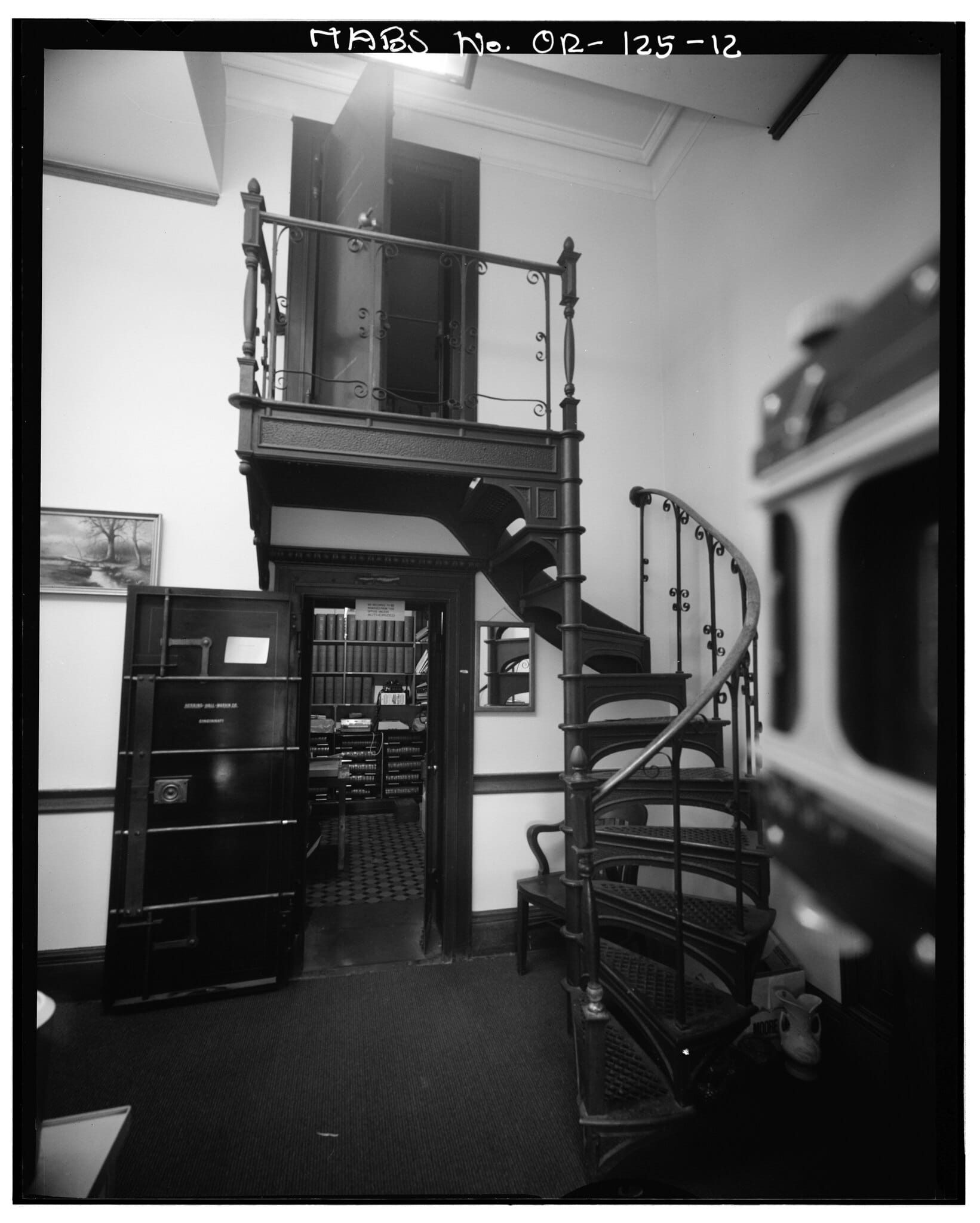

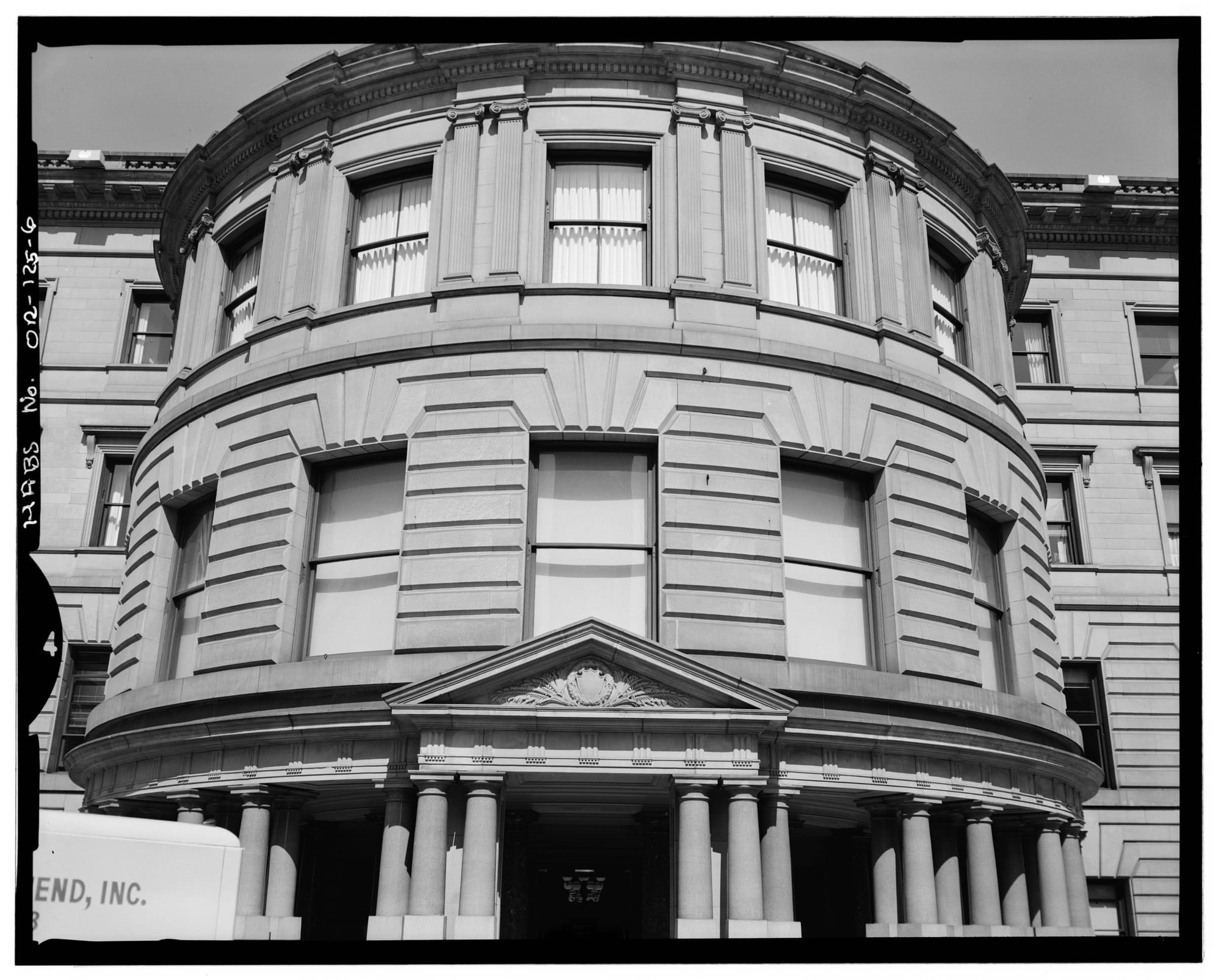

So, what’s changed? More trees on the street and the Charles Luckman & Associates-designed Wells Fargo Center now looms over city hall, but the building itself is shockingly unchanged–at least on the exterior. Inside, a handful of major renovations over the years once "brutalized" the space, before a mid-1990s one repaired some of the damage, improved its seismic safety, and improved the quality of the office space.

Flourishing through natural resource extraction, waterways, and the railroad, by the 1880s the government of Portland needed a city hall from which they could lead Portland’s evolution from a western boomtown into a modern metropolis.

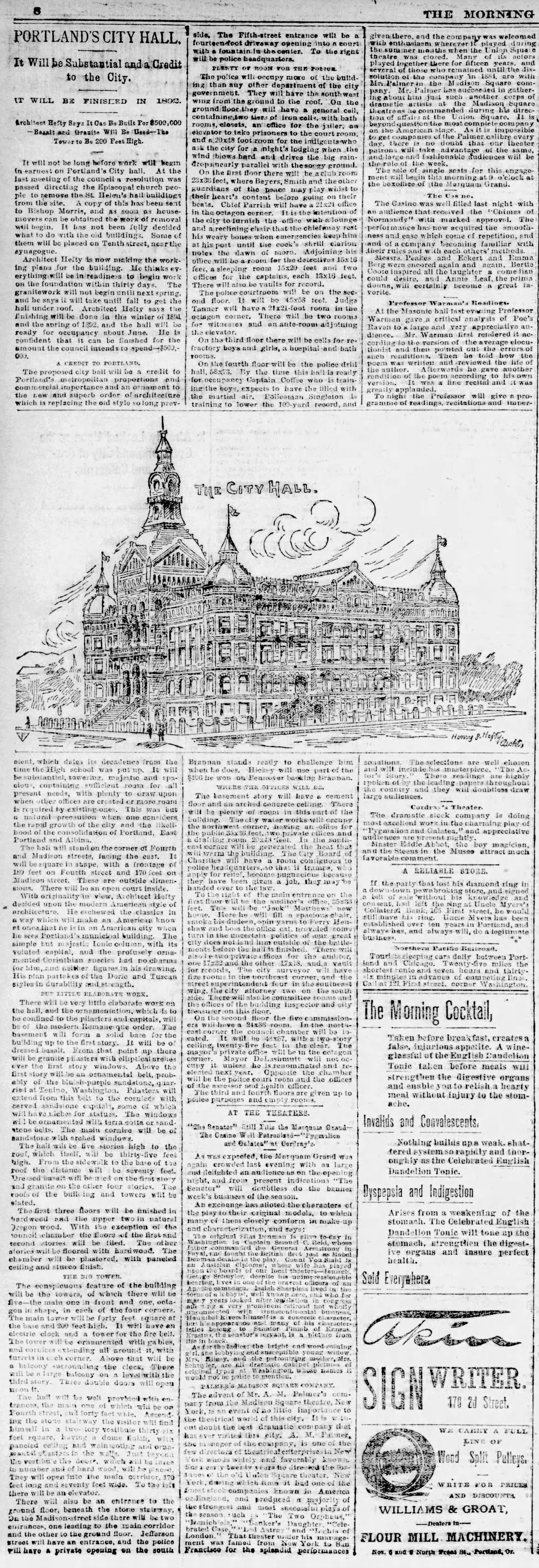

1890 request for entries for the design competition and article about opening the entries.

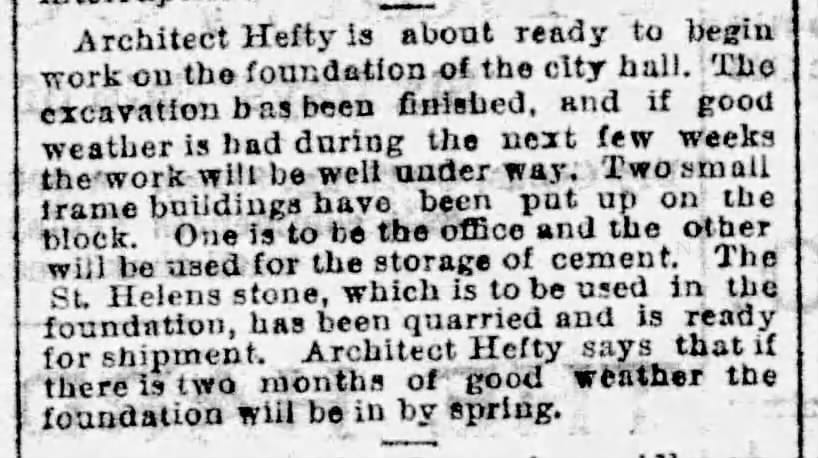

1890 articles about the structure of the competition, Hefty's win, his plans, and the start of foundation work.

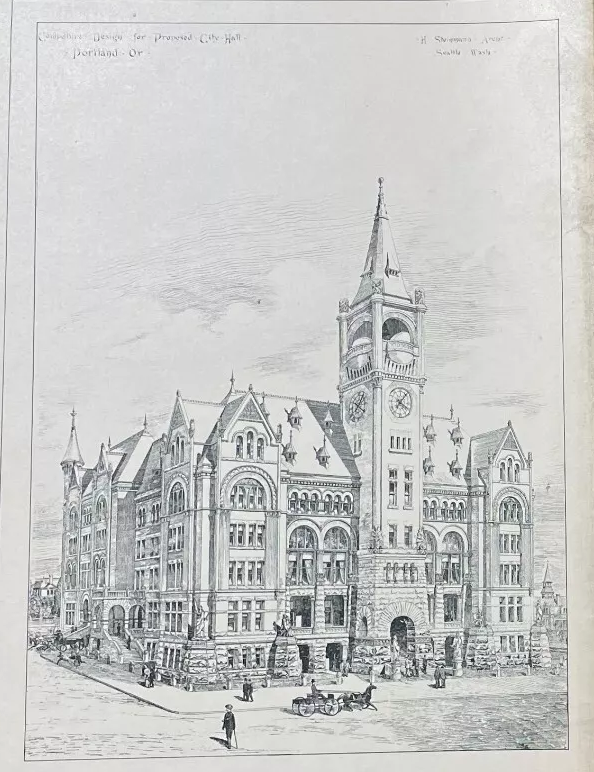

After slow progress on site selection and financing, the Portland City Council invited architects to submit plans for the design competition in spring 1890. Proposals from Hermann Steinmann and John Parkinson of Seattle won prizes, as well as Portland’s McCaw & Martin, but eclectic Swiss-American architect Henry J. Hefty won the commission. Hefty proposed an extravagant Second Empire bauble topped with a tower, and construction began in 1890.

Henry Hefty's winning proposal for the new city hall, Portland City Archives | Hermann Steinmann prizewinning (but not selected) proposal, American Architect & Building News, January 1891

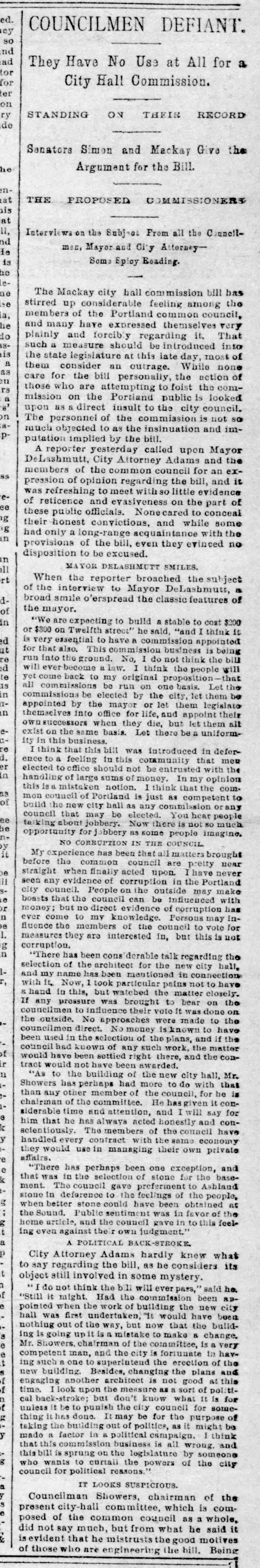

Work proceeded slowly, though, and in the meantime the new city hall became tied up in a power struggle between the Portland city council and the Oregon state legislature. In 1892 the Oregon State Senate voted to wrest control of the project away from the city of Portland and hand it to a state-formed New City Hall Commission, asserting that it would speed construction, free up the council to focus on governance, and dispel perceptions of “jobbery” (public corruption connected to patronage). The Portland commissioners were pissed, arguing that–while they would have accepted the state’s involvement in the beginning of the process–it made no sense to make this change with an architect chosen and construction underway (which, yeah).

Home to a larger Portland delegation, the Oregon House of Representatives voted down the commission plan multiple times, but eventually it was attached to another piece of legislation and successfully passed–the New City Hall Commission assumed oversight of the building project.

1891 articles about the Portland City Council opposing the bill to take their control of the city hall building process, the new commission considering scrapping Hefty's plans, and the confirmation of the change to Whidden & Lewis

Belying the state’s argument about speed, the new commission took months to start work. Eventually, citing uncertainty around rising costs and questions of taste, they scrapped Hefty’s plans for city hall–but they were still on the hook to pay out his contract. Given the cost of paying him off, digging up the newly-laid foundation, hiring a new architect, and–you know, actually building the city hall…I’m skeptical that cost was the real driver here. It seems just as likely that this was a story of the new commission–beholden to a different power base–wanting to have their own guys in there.

A shift in local power, rippling through different patronage networks, filtered through the practical needs of the client and site, and Portland gets a very different city hall than they initially intended–whichever one was built, it all feels quite contingent and arbitrary for something that will presumably be the heart of city government for centuries.

The New City Hall Commission’s chosen architects, Whidden & Lewis, were a premier Portland firm from the 1890s into the 1910s. William M. Whidden first came to the city while working for New York megafirm McKim, Mead, & White to supervise the construction of the Portland Hotel. He liked it enough to eventually make Portland his permanent home. Partnering with his college buddy Ion Lewis, the firm worked across a variety of revival styles on commercial, civic, and educational projects as they grew into one of the city’s most productive and prestigious firms–maybe the New City Hall Commission just wanted the glamor of working with a more fashionable firm (although Hefty was an influential architect in his own right).

1905 photo, Portland City Archives | 1972 photo with the new city council, Portland City Archives | 1970s photos by Marion Dean Ross (streetscape with man, facade detail, and streetscape with car)

Portland City Hall, Italian Renaissance Revival with Mannerist influences, opened in 1895. Despite only rising a handful of floors, it was an early example of steel-frame construction in Portland–there were never-realized plans to pop a tower on top. Pink and gray with Doric columns and an open loggia, it’s an earnest precursor to the winking, playful postmodernism that would arise nearly a century later.

Portland City Hall has been a focal point of power and protest for 125 years this January, as the city bloomed from an ambitious provincial city into a mature metropolis, and in 1974 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

1981 Historic American Building Survey photos by Dallas Swogger, Library of Congress | 2008 photo, Wikimedia Commons

Production Files

Further reading:

- NRHP Nomination Form

- Frozen Music : A History of Portland Architecture by Gideon Bosker and Lena Lenček

This cracked me up.

Some people were not especially pleased with the state taking over the new city hall project, judging by this withering sarcastic letter to the editor and complaints about the new commission's lack of initial activity/haste.

Member discussion: