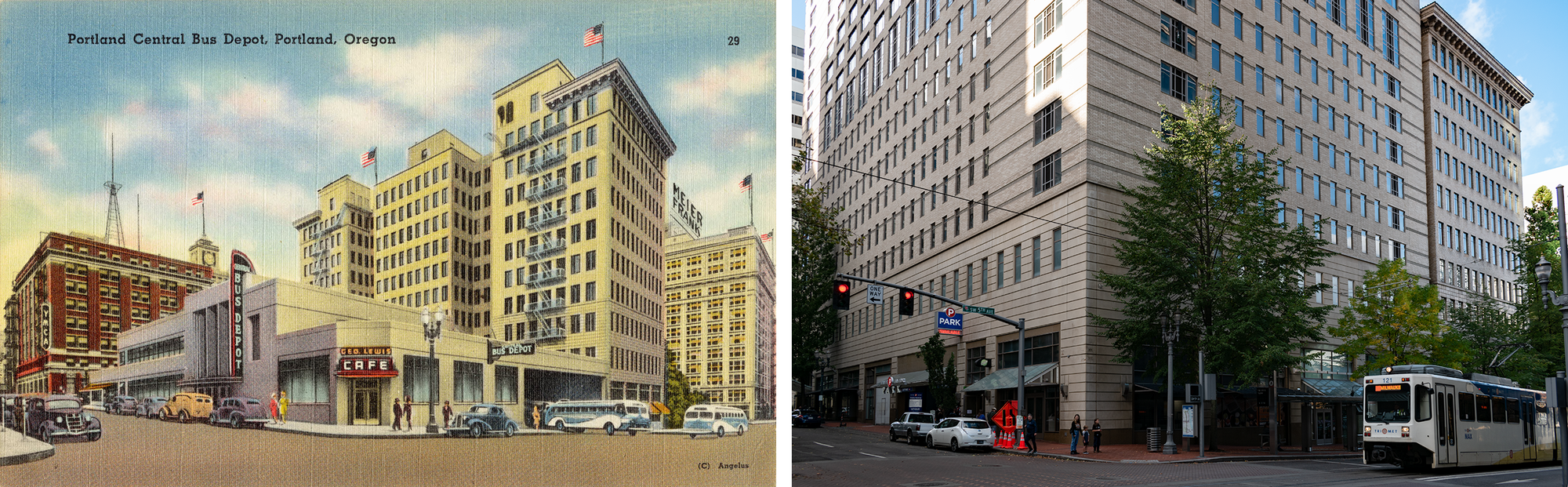

From 1938 until 1985, this handsome Streamline Moderne bus terminal kept waiting passengers out of the Portland rain. Now, it’s the coldest city in the US without an intercity bus terminal–travelers today must wait outside after this station’s successor closed in 2019.

The closure of the Portland Greyhound terminal is part of a broader withering of the US intercity bus system over the last decade, as the industry was neglected by the federal government–the CARES Act rescued the airlines, but intercity buses received no direct aid–and picked over by vultures like hedge fund Alden Global (who–not content with gutting our newspapers–have snapped up bus terminals across the country, closed them, and flipped them for development).

Long before that, though, this bus terminal–designed by Knighton & Howell with W.D. Peugh–opened in 1938. Originally known as the Union Stage Terminal Building, it centralized the operations of Greyhound, Trailways, Gray Line, and other intercity buses in Portland.

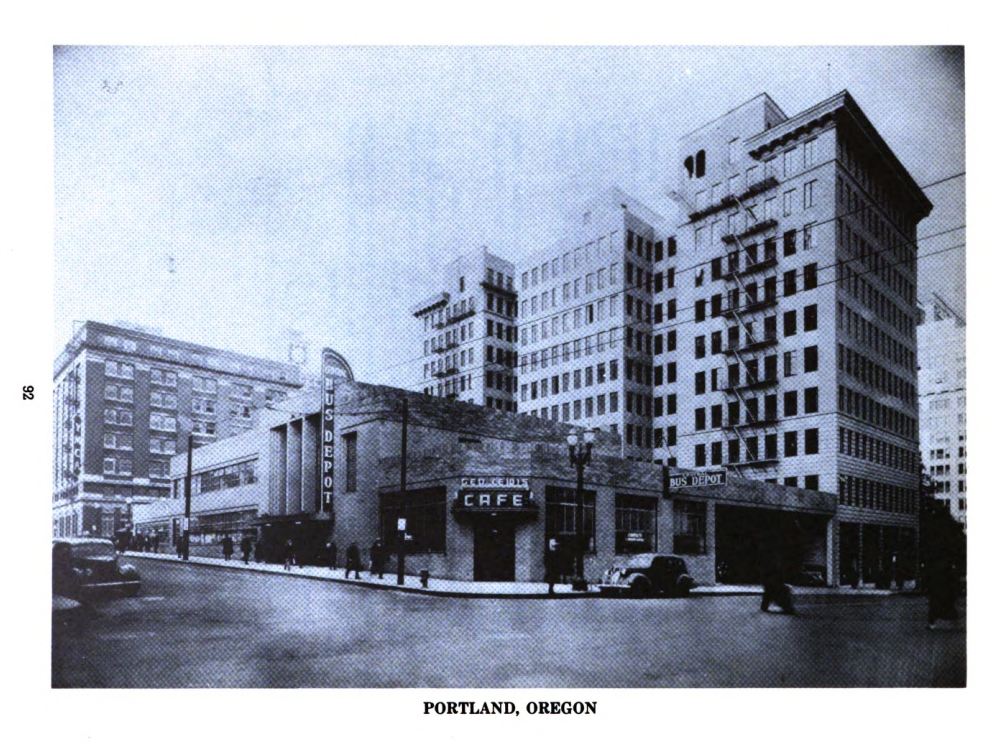

So, what’s changed? Probably easier to start with what hasn’t, since there’s basically only one building remaining–the Pacific Building, the office building to the right of the bus depot. Designed by A.E. Doyle, Chicago School with hints o Italian Renaissance Revival, it opened in 1926. Other than the Pacific building, though, this streetscape is completely remade. Some changes were good–the Green and Orange lines of the MAX Light Rail opened on SW 5th Avenue in 2009. Others were kinda meh–semi-vacant after Greyhound moved out in 1985, the old Central Bus Depot was demolished in 2000 and replaced by the Hilton Executive Tower hotel, which opened in 2002.

By the late 1920s intercity bus travel had grown into a major form of travel in the US (it was pretty easy to be competitive when you used right-of-way paid for by the public, in comparison to the railroads who had to build their own). Both the City of Portland and the private bus companies recognized an increasing need for a bus terminal to centralize the city’s myriad bus services, decrease congestion, and create a modern gateway into the city. However, financial challenges from the Great Depression, bureaucratic paralysis in the city government, and a reluctance from the private bus companies to invest in infrastructure (pfffft, that’s for the railroads) stalled plans for years.

The bus companies finally pushed ahead in the late 1930s. Their plans for a central terminal didn’t fulfill the requirements laid out by the City of Portland or address some of the congestion issues, but it was financially feasible, which was good enough.

The bus terminal replaced the Henry Corbett House, a Victorian mansion built on the then-outskirts of the city for one Portland’s early business leaders in 1875 and swallowed up by downtown Portland over the years.

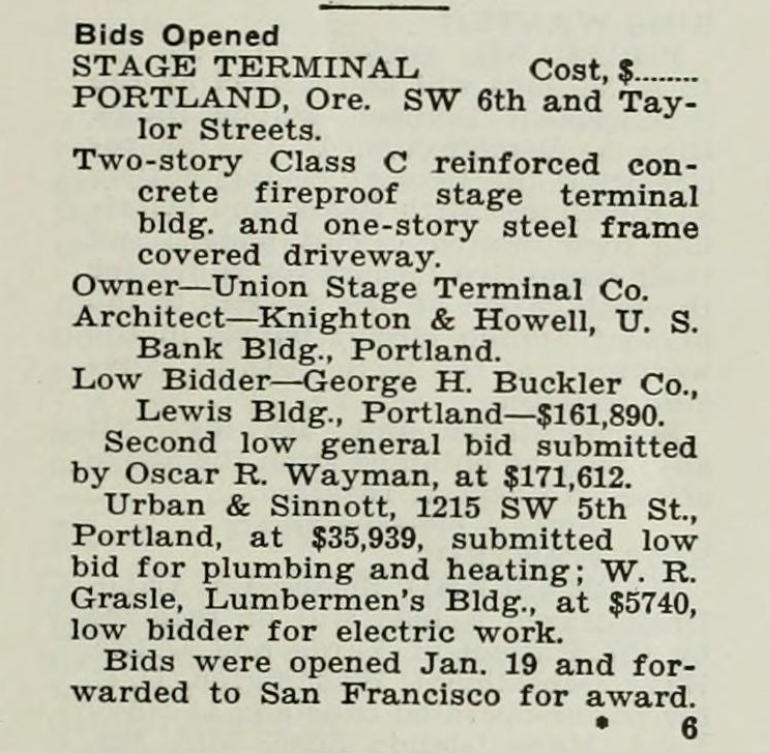

Portland firm Knighton & Howell was hired to design the new Union Stage Terminal, together with W.D. Peugh out of San Francisco. William Christmas Knighton was an influential architect in Oregon–he was the first State Architect of Oregon, and the second architect licensed to practice in the state. Working in the Arts & Crafts style and various revival styles, Knighton designed a bunch of civic buildings, schools, and homes across Oregon. He partnered with Leslie Dillon Howell in 1922, forming Knighton & Howell, but by then his career had arguably peaked. The Portland Central Bus Terminal was the last building that Knighton signed off on, as he died in 1938, but I can’t imagine he did much work on it himself–Knighton didn’t really do modernism.

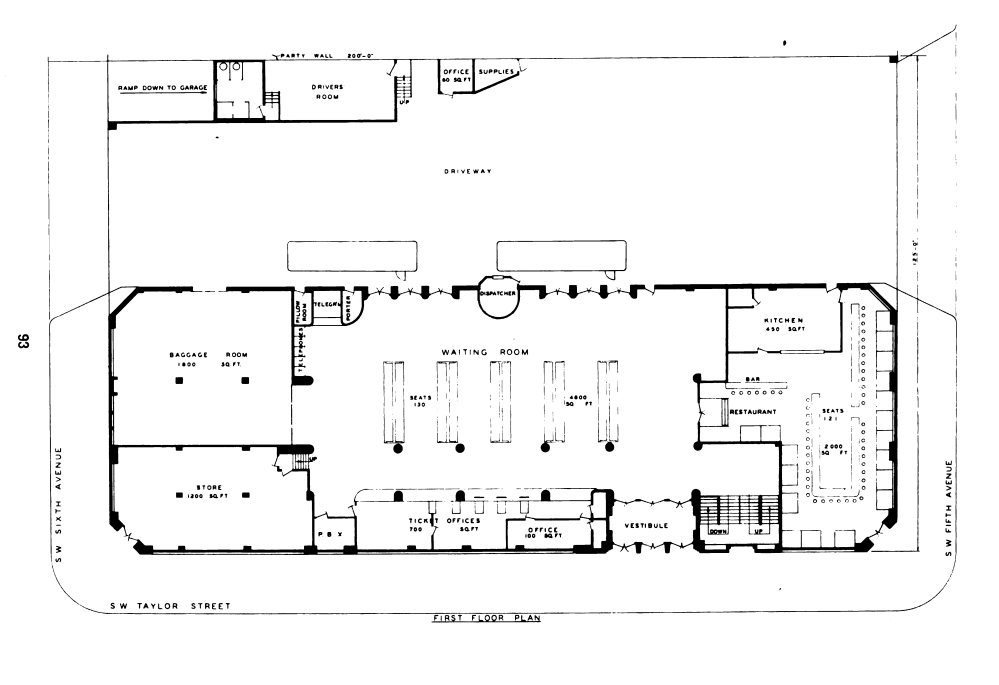

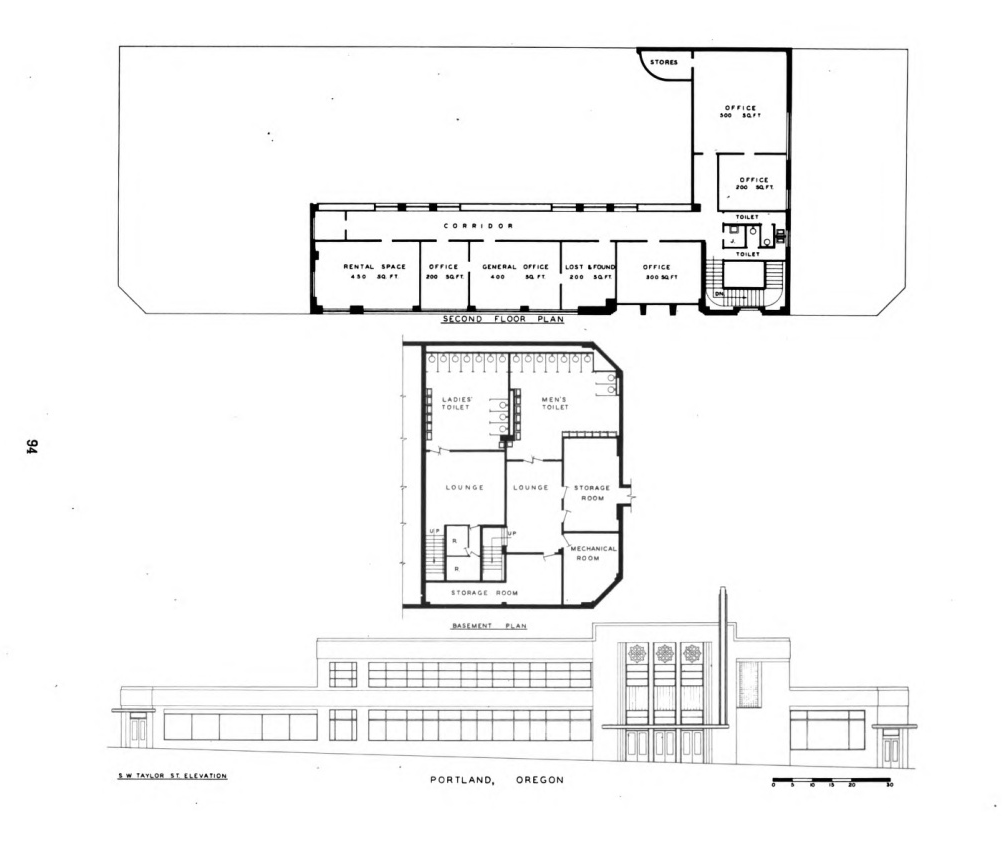

Bids opened, 1938, the Pacific Constructor, the Internet Archive | Floor plans from Modern Bus Terminals and Post Houses, edited by Manferd Burleigh and Charles M. Adams, 1941, HathiTrust

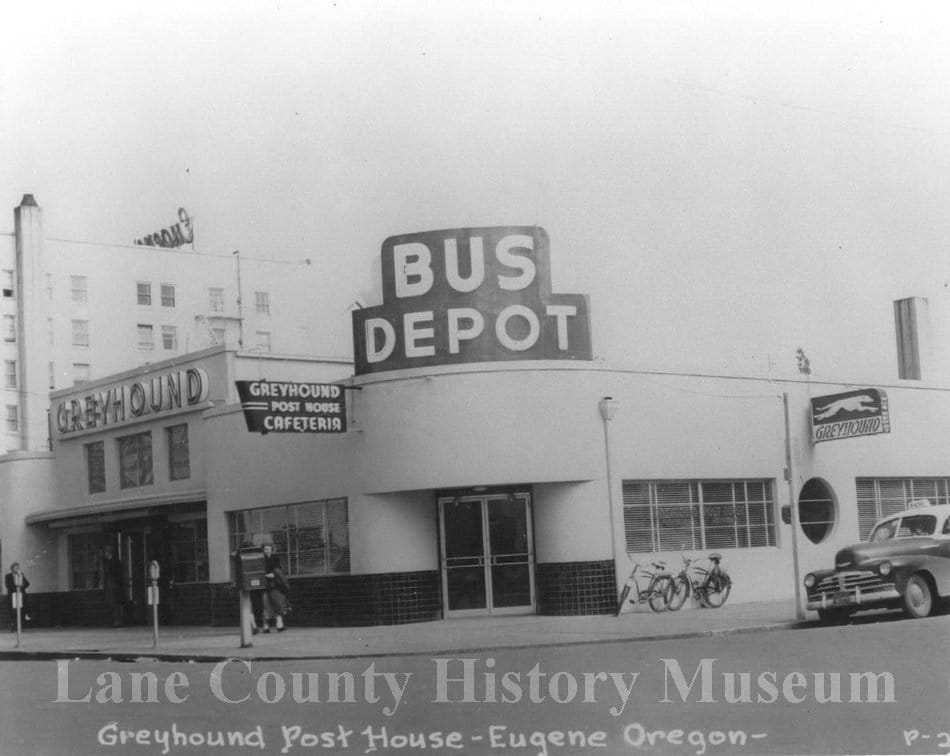

By the late 1920s, the firm though was designing commercial buildings in a more progressive style, which would culminate in the Portland Central Bus Terminal. While the Portland terminal is long gone, it actually has a surviving sibling–around the same time, Knighton & Howell designed the former Greyhound terminal in downtown Eugene, which opened in 1940 and still stands.

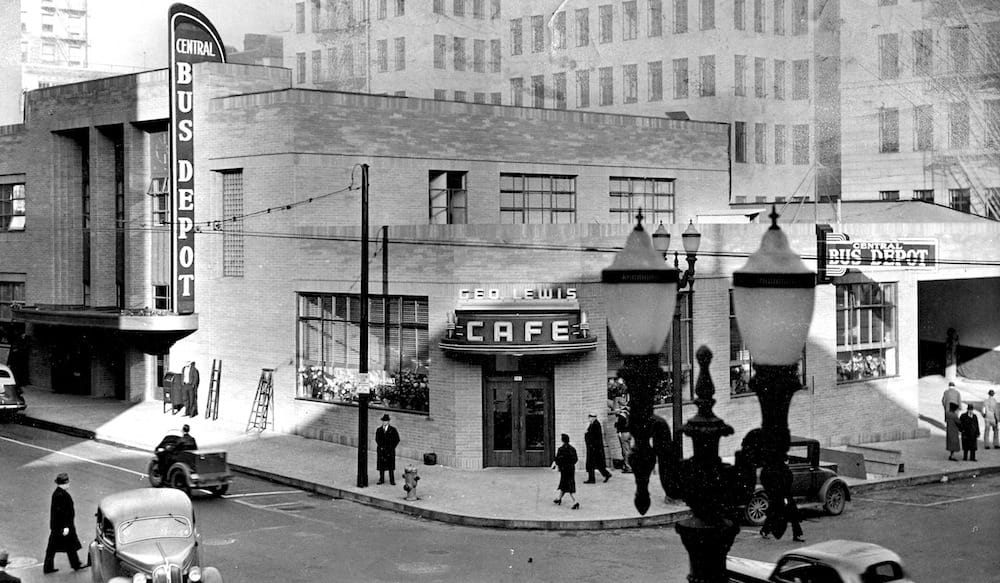

Portland Central Bus Depot, 1938, Portland Then & Now | Eugene Greyhound Bus Depot, 1948, Lane County History Museum

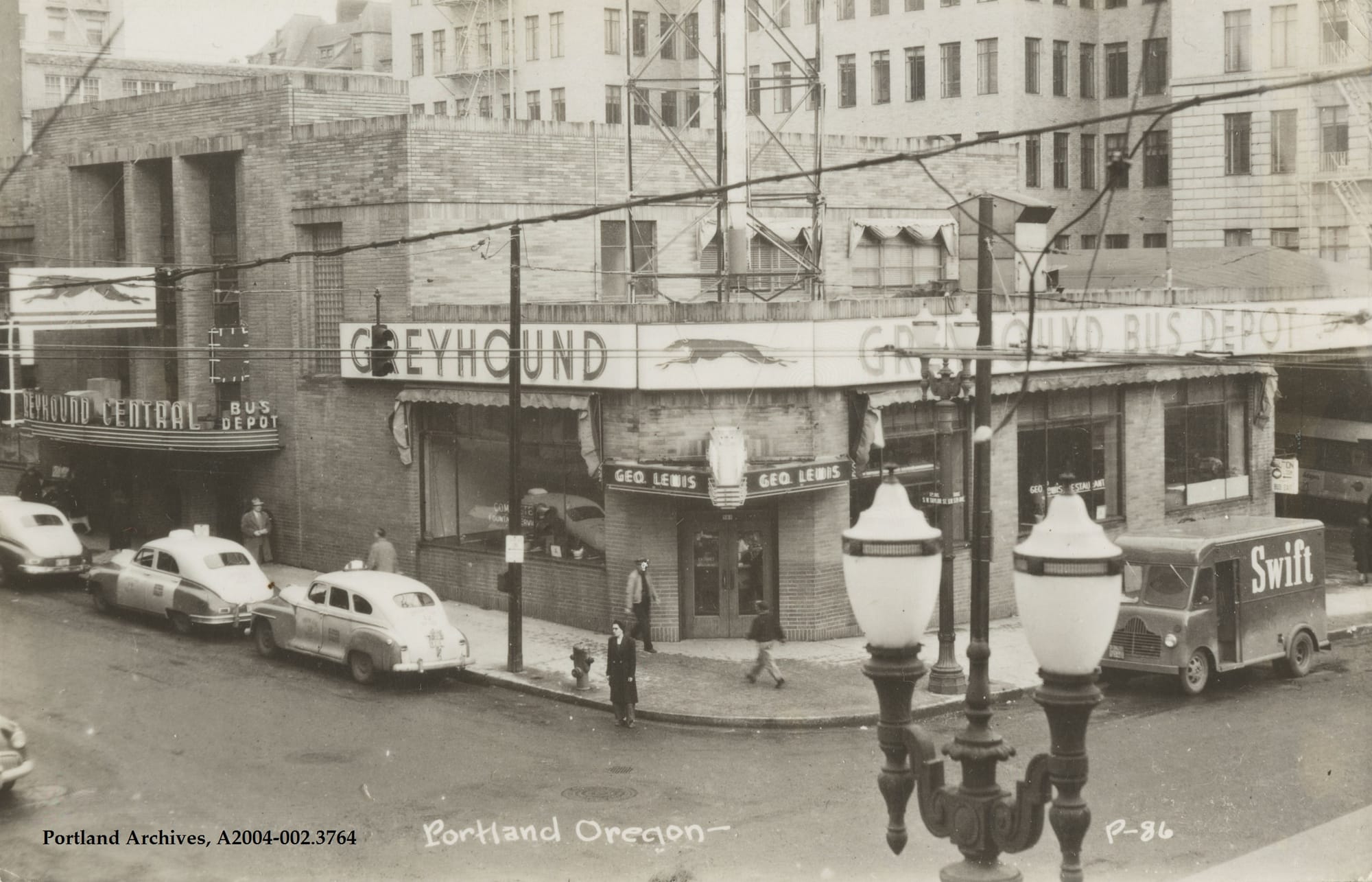

Utilitarian streamline moderne, the Portland Central Bus Terminal was a homely cousin of the dashing William Arrasmith-designed Greyhound stations that popped up around the US in the late 1930s and 1940s. More than 10 bus companies used the new depot when it opened in late 1938, and for decades it held bathrooms, ticket offices, seating, and a cafe (the Geo. Lewis Cafe the longest-tenured) for passengers.

Exterior and interior photos, from Modern Bus Terminals and Post Houses, edited by Manferd Burleigh and Charles M. Adams, 1941, HathiTrust | 1948, City of Portland Archives | Undated, Oregon Historical Society | 1949, City of Portland Archives | Undated, Marion Dean Ross, Design Library, University of Oregon Libraries

Portland's 1972 Downtown Plan reimagined the center of the city, especially the area around the aging bus terminal, and in 1978 this stretch of 5th Avenue was turned into the Portland Transit Mall, a TriMet busway. Plans to relocate the Greyhound terminal also began in the 1970s, culminating in a move a mile north to a new terminal near Portland Union Station–the last bus rolled out of the Portland Central Bus Depot in 1985.

After Greyhound left, the semi-vacant old bus terminal housed a few nightclubs in the 1980s and 1990s until it was demolished in 2000. The Hilton Executive Tower hotel rose up in its place, designed by Zimmer Gunsul Frasca and opened in 2002. Now rebranded as the Duniway, it remains a Hilton property.

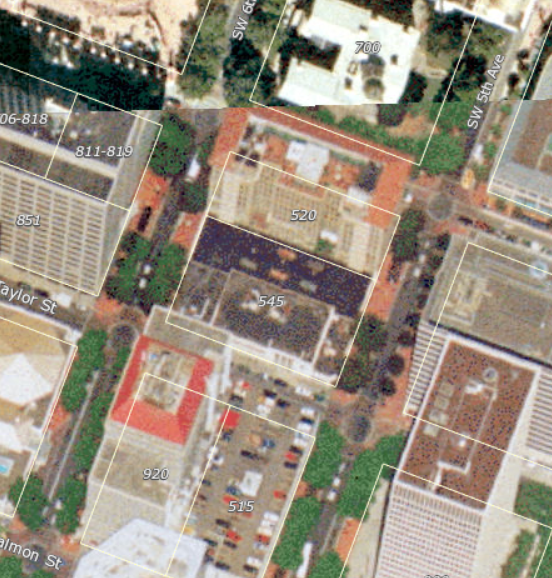

1960 aerial, 1999 aerial, 2001 aerial, 2002 aerial, all via PortlandMaps

The decline of US intercity buses creates a depressing epilogue here–Greyhound's replacement terminal closed in 2019. Buses remain the most cost-effective means of travel in the US, and intercity bus passengers are disproportionately likely to be low-income, people of color, or disabled. With the closure of its Greyhound station, today all intercity buses in Portland load curbside, and those passengers have nowhere comfortable, dry, and warm to wait for a delayed bus. Portland isn’t unique here either–many major US cities have lost their bus terminals in the last decade, with Chicago about to join them if the city doesn’t get its act together in the next month.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Intercity bus transportation in Oregon: preliminary report, 1976

- In Faded Portland

- WC Knighton and/or Knighton & Lowell NRHP properties include the Joseph Gaston-William Holman House, the Roseburg Oregon National Guard Armory, the Trinity Place Apartments, the Frigidaire Building, and maybe in the future the Eugene Greyhound Bus Terminal

Member discussion: