An unusual adaptive reuse journey in Portland–from car dealership to bank offices to local government–was nearly capped off with an impressively bonkers bit of public art, a "green roof sculpture” with a 50-foot windmill, earthen mounds, and a tree atop a rotating platform.

Heavily altered but still standing, it’s a testament to the sturdy automotive architecture of the 1910s and 1920s that this building is on its third productive use a century later–hard to imagine, like, a 2000s Chevy dealership in the suburbs stripped to its bones and converted into something else. Built as the Francis Motor Car Company dealership and service center in 1920, a 1980s renovation converted it into offices for Benj. Franklin Savings & Loan and added the taller building next door. Multnomah County were the ones who almost crowned the building with an ambitious rooftop sculpture by Canadian artist Noel Harding, commissioned as part of the county’s Percent for Art program when they moved their offices here in 2000–cost and feasibility concerns unfortunately scuttled those plans.

So, what’s changed? Well, literally everything. I’m sure there are some walls, beams, and structural stuff deep in there from its original iteration as a car dealership, but the 1980s rebuild replaced the facade and fused the building with a new midrise. Besides the general shape and massing, all exterior remnants of the building’s former life have disappeared–it's hard to believe that this is the same structure.

Before all that, though, it was built as the Francis Motor Car Company’s dealership and service center. The company’s founder, Clarence E. Francis, entered the automobile market early, opening Portland’s first used car dealership in 1909. After a false start in 1914 selling new Briscoe cars, Francis successfully broke into the new car game in 1916 when Ford granted him the franchise to Portland, where the company also had an assembly plant.

1919 and 1920 articles on the new Francis Motor Car Co. building | 1920s photo, Angelus Studio photographs, University of Oregon | 1947 ad from a University of Oregon football program, the Internet Archive | Late 1950s photo, Multnomah County Archives | 1960 land use slides, Portland City Archives |

Growing fast, Francis Motor Co. hired Martin & Wipper to design a new headquarters east of the Willamette River. With showrooms, offices, a machine shop, an auto body shop, and warehouse space, the new facility opened in 1920. By 1928 C.E. Francis was the largest Ford dealer in the state of Oregon. Sometime later in the 1920s the company added two floors to the building's north side, making the entirety of the Grand Avenue elevation three stories.

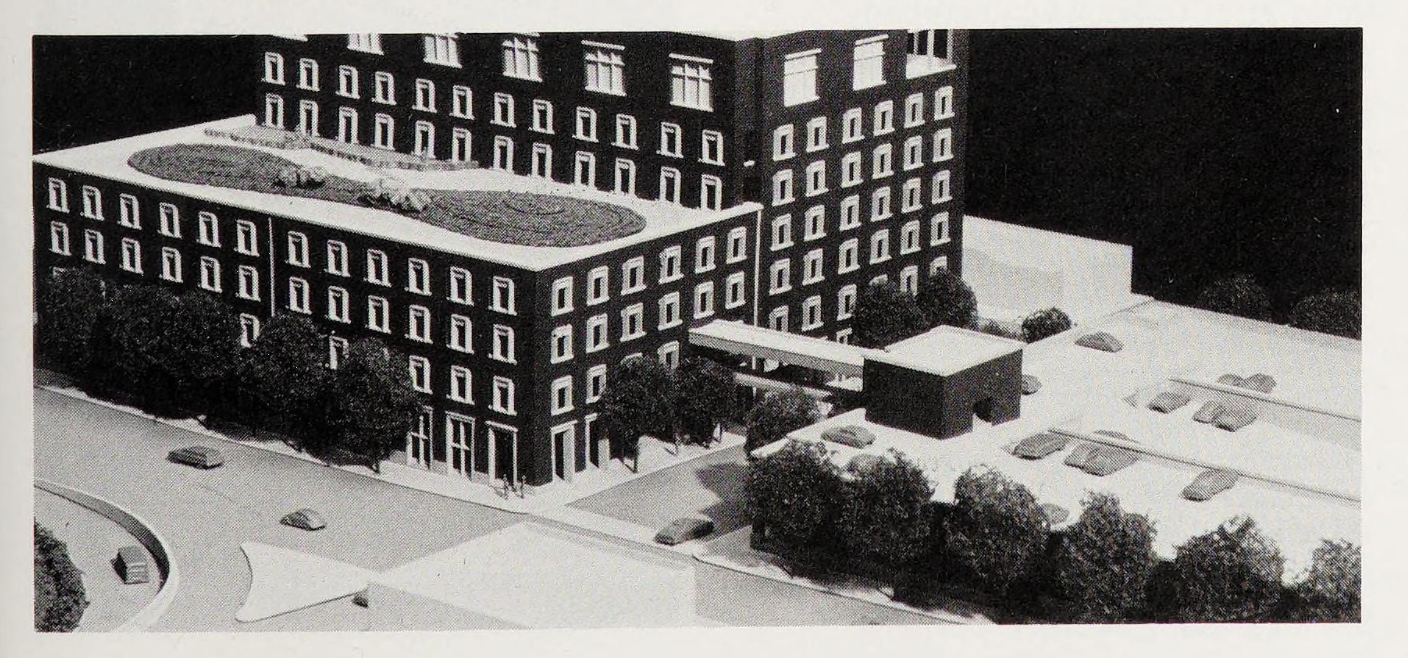

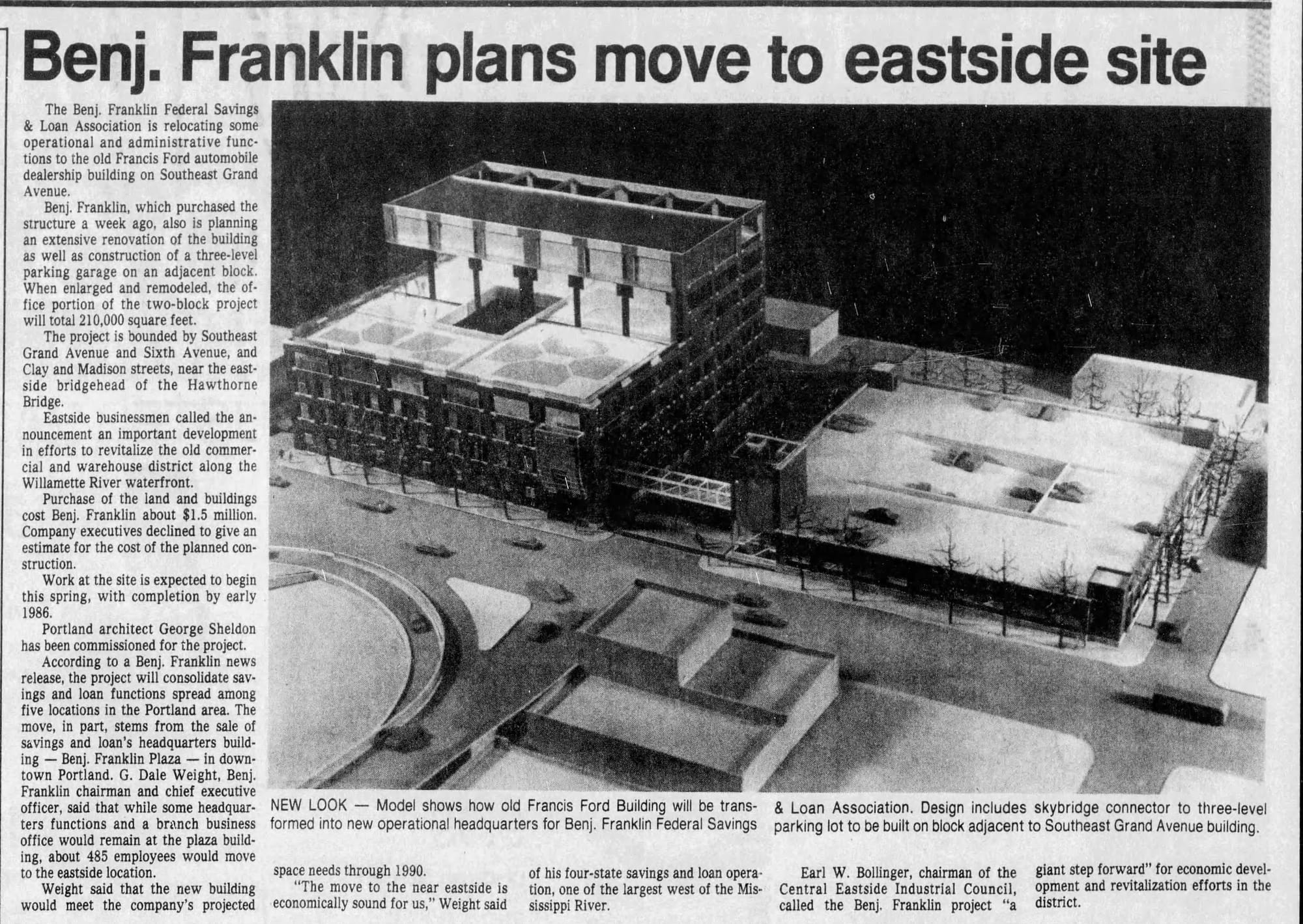

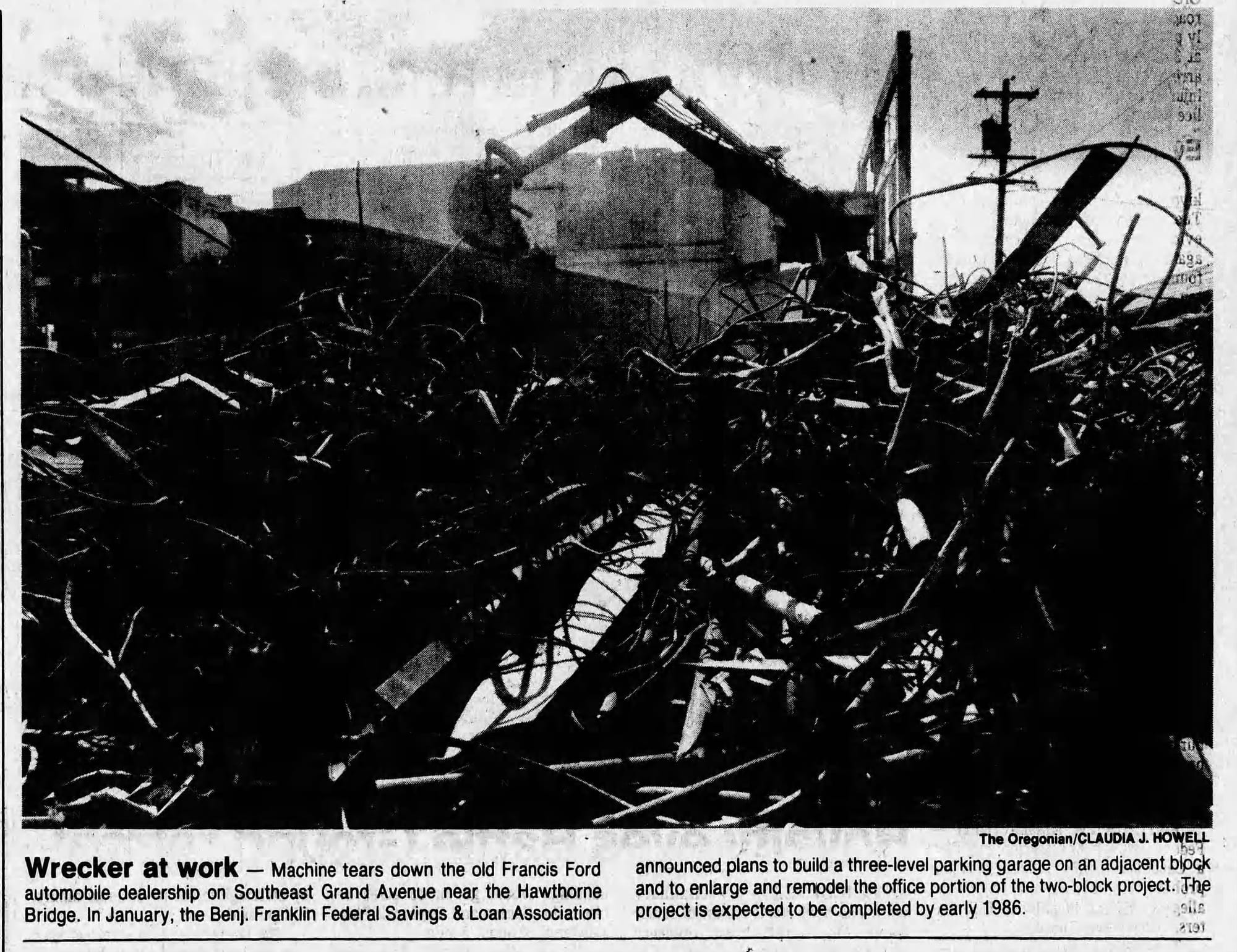

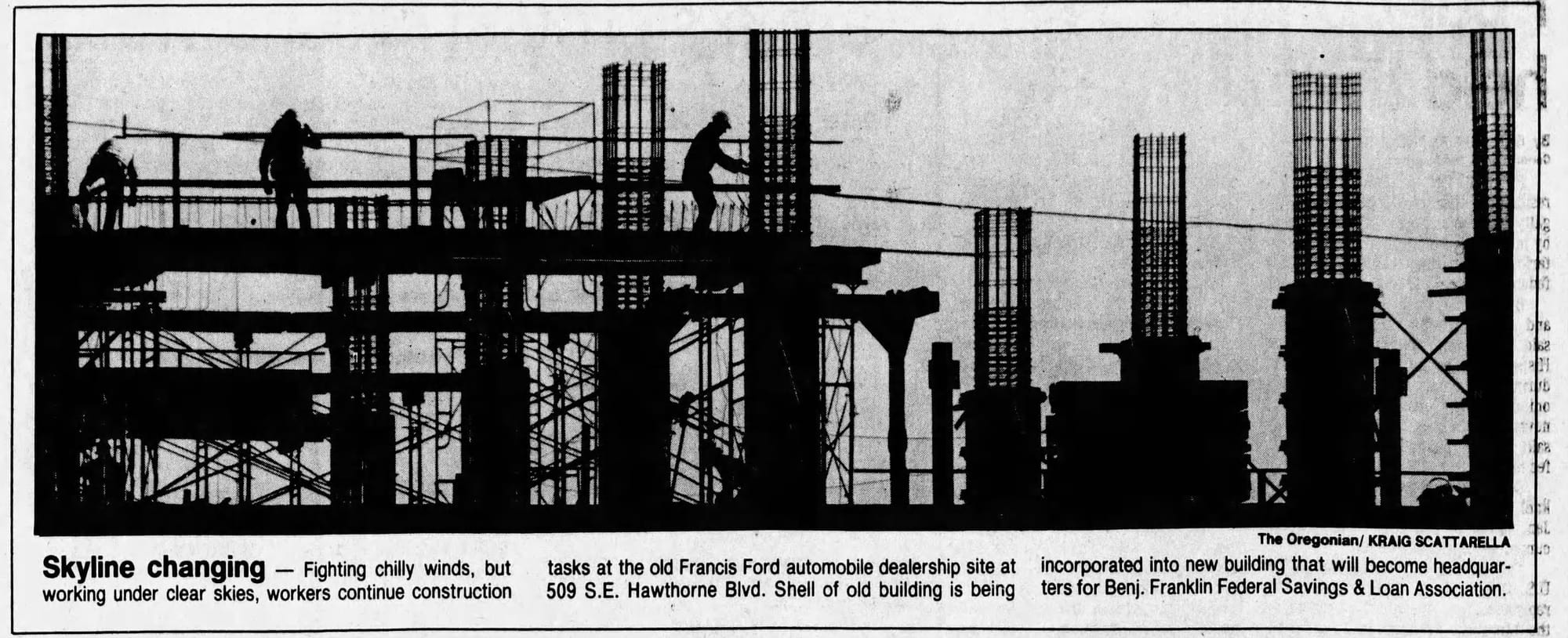

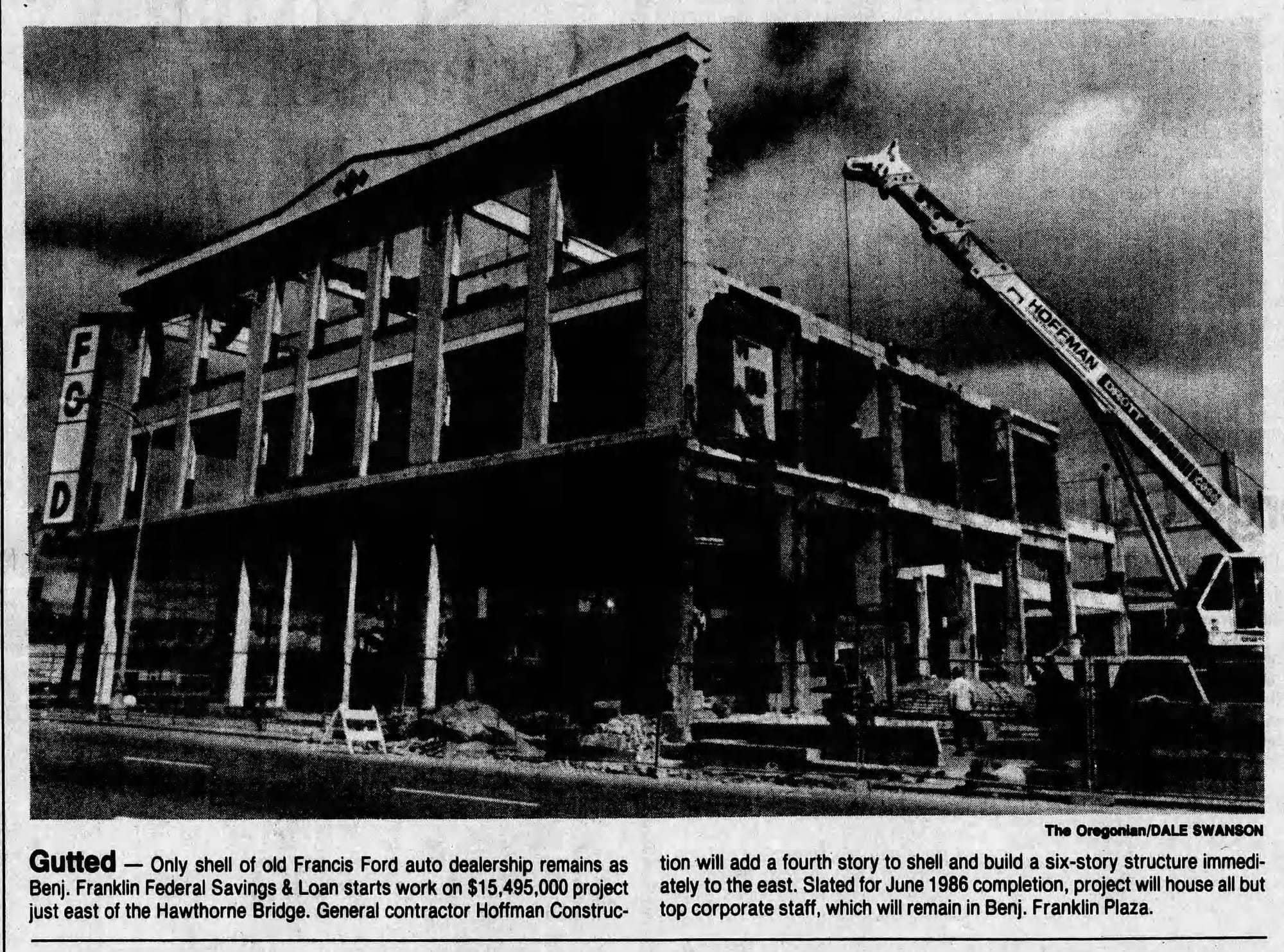

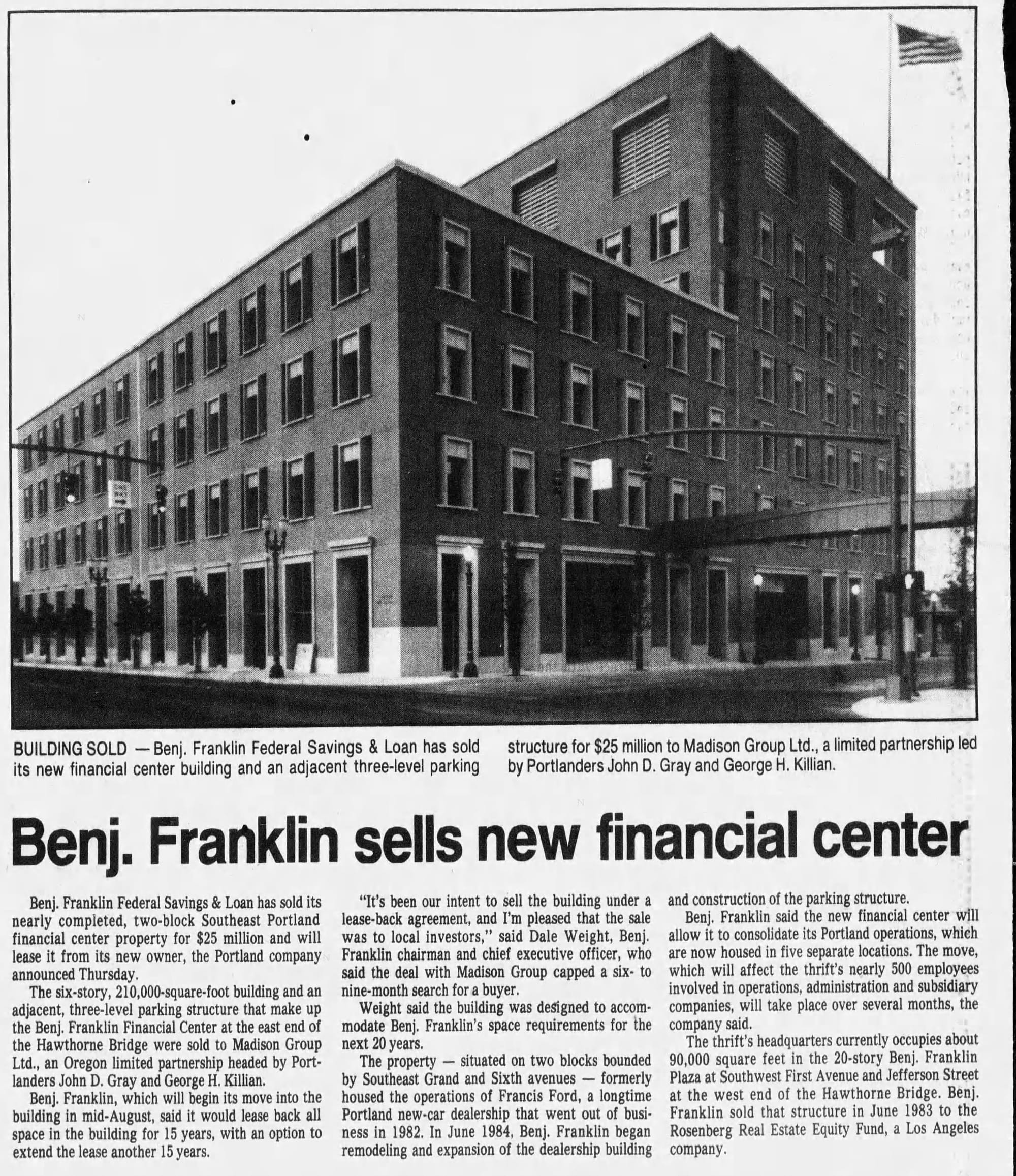

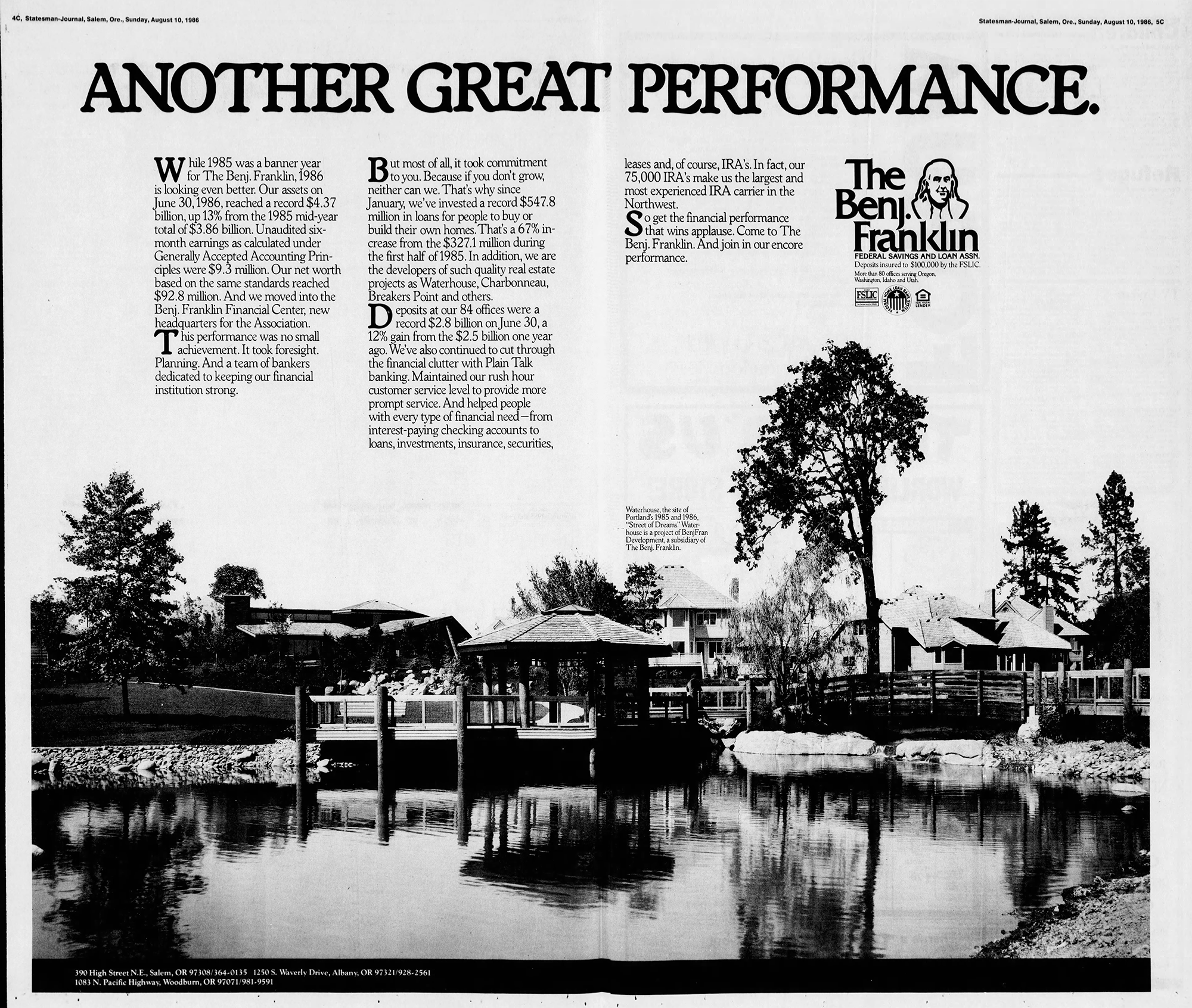

After more than six decades here, Francis Ford decided to focus on their suburban locations and closed in 1982. The property was bought by Benjamin Franklin Savings & Loan, a major “thrift” based in Portland (thrifts are bank-like, but not banks–catering exclusively to consumers rather than businesses, they focus on savings deposits and mortgage lending). Benj. Franklin hired SERA Architects to turn the block into a sizable new office, mixing reuse and new construction. Building a new midrise on the Francis Ford parking lot and connecting it to the old building, they stripped the old dealership down to its bones and gave it a new brick and concrete facade. The Benj. Franklin Financial Center opened in 1986, a shiny new home for a confident and growing financial institution with $4.5 billion in assets, 33 offices in Portland, and 83 across the state.

1981 photo, Portland City Archives | Benj. Franklin Financial Center model | 1984-1985 articles and photos of the gutting and renovation of the car dealership into an office building | 1986 year-end ad | Ad in Forbes, 1988, the Internet Archive |

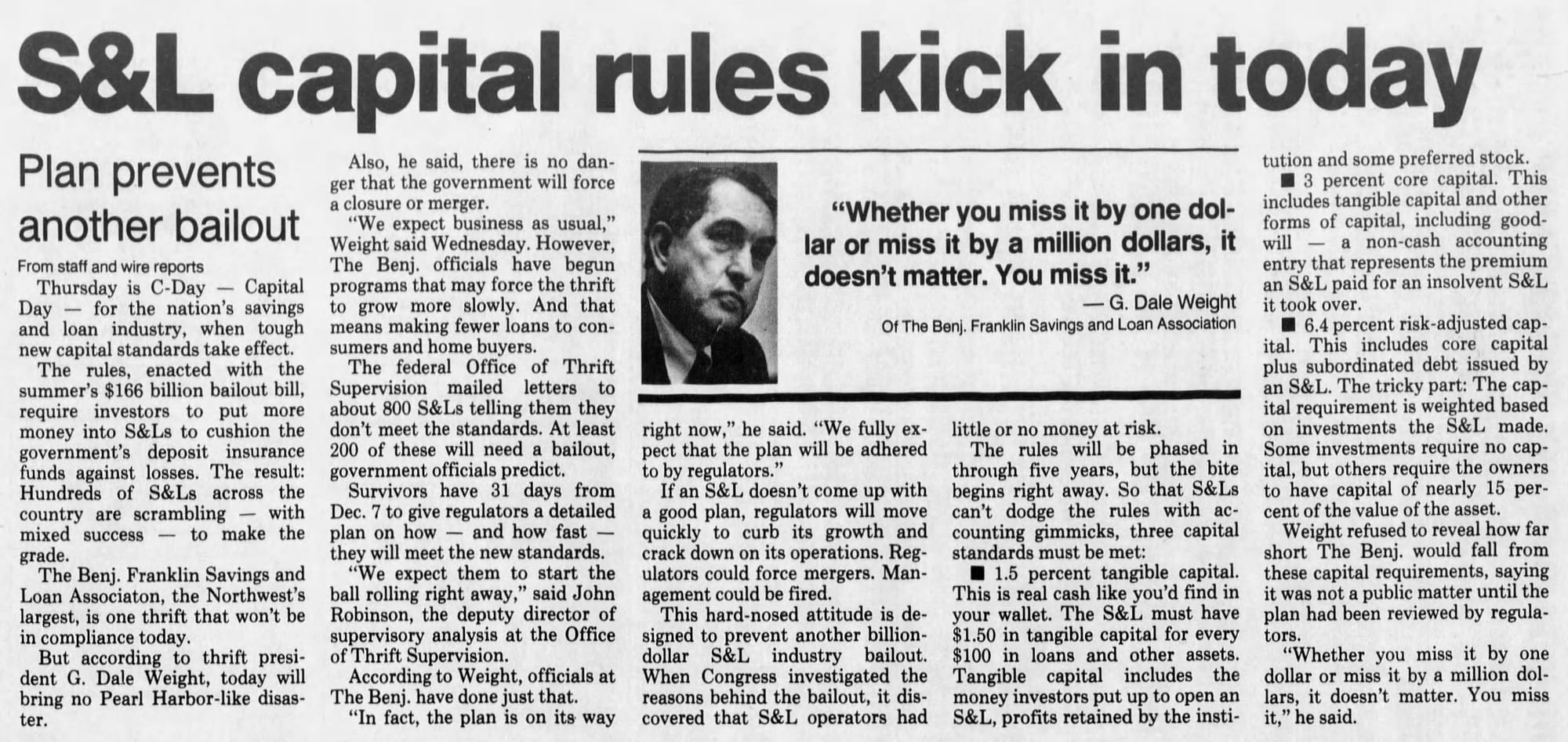

Benj. Franklin was an S&L in the 1980s, though, with all the doom that portends. Reaganite deregulation and high interest rates coalesced into the savings and loan crisis in the 1980s, devastating thrifts across the US. Initially one of the stronger savings and loan associations, as the crisis began to unfold in the mid-1980s Benj. Franklin acquired multiple failing thrifts at the behest of federal regulators. Absorbing those failing thrifts strained the company, but it muddled on until the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 changed how the liabilities of those acquisitions appeared on the lender’s balance sheet. With the pendulum swinging back a bit towards regulation (belatedly, awkwardly), Benj. Franklin was now way out of compliance. The company’s balance sheet suddenly appearing quite suspect, the federal government declared the S&L insolvent and seized Benj. Franklin, selling it off to Bank of America in 1990.

1989 articles about the new regulations and their effect on Benj. Franklin and 1990 articles about the Bank of America takeover

The seizure set off a wave of lawsuits, most of which the federal government lost, but by that point Benjamin Franklin Federal Saving & Loan was gone. Bank of America owned the building after taking over Benj. Franklin, but they leased out the still-new office building to the U.S. Bancorp of Oregon in 1992. That bank was itself acquired in 1997 by Minnesota’s First Bank System, who took on the US Bancorp name. After the acquisition, US Bank laid off more than 2000 people in Oregon, vacating this building again. Turning a parking lot and an obsolete car dealership into modern bank offices must’ve been a sizable undertaking, but bad luck and bad policy had left the complex looking for a new tenant for the second time in only 15 years. Bank of America sold the building to Multnomah County for $25m in 1999 ($47m today).

Multnomah County wanted to convert the dealership-turned-bank into its administrative headquarters and the seat of county government. The project qualified for the county’s Percent for Art program, which sets aside 1% of the construction budget of major county capital improvement projects to fund public art. The Regional Arts & Culture Council (RACC) selected Canadian artist Noel Harding for the commission. On top of the former Francis Ford building, Harding proposed a “green roof sculpture” consisting of a 50-foot windmill and a rotating platform with an earthen mound covered in native grasses and a tree, all to be irrigated with water pumped by the windmill.

This proposal was right in Harding's wheelhouse–he spent the 1990s creating fanciful, and functional infrastructure eco art. Two years prior he’d completed the Elevated Wetlands, a quirky water filtration installation in a Toronto park that cleans water from the Don River–the wetland flora growing inside Harding's sculptures absorb and remove chemical pollutants.

Harding’s proposal in Portland was whimsical, weird, and ambitious, but the Multnomah County Commissioners were not fans of the RACC’s choice. There was a mild uproar, with opponents raising regulatory, technical, and feasibility concerns. Ultimately, they canceled Harding’s project–the RACC worried it could devour the organization’s entire annual maintenance budget. Instead, the Multnomah County Building received bronze bas-reliefs by sculptor Wayne Chabre, which line the building's Hawthorne Boulevard side. While Harding’s windmill and rotating platform were never built, the building did end up with a green roof anyway–the Amy Joslin Memorial Eco Roof was completed in 2003.

Wayne Chabre's Connections, 2022

Serving as the county headquarters and seat of government, the Multnomah County Building houses the offices of the County Chair, the Board of County Commissioners, and various departments like Assessment & Taxation, Sustainability, and Community Involvement. In 2004, the building was the site of the first same-sex marriages performed in the state of Oregon.

Spanning the destructive optimism of the early automobile era, the economic wreckage of the savings & loan crisis, and hard-fought progress in civil rights, this strange survivor feels like an especially American story.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Portland: Gateway to the Northwest by Carl Abbott

- Portland's Hawthorne Boulevard by Rhys Scholes

- NRHP registration form for Clarence E. Francis' (NRHP-listed) house in Portland, providing a background on the company

- On the Noel Harding green rooftop sculpture:

- On Wayne Chabres bronze bas-relief piece, Connections

A couple more photos from the late 1950s where the building is barely visible.

In 1920 a two-year-old used Chevy or a used Oakland Motor Company Six bought at Francis cost the equivalent of $10k today.

Member discussion: