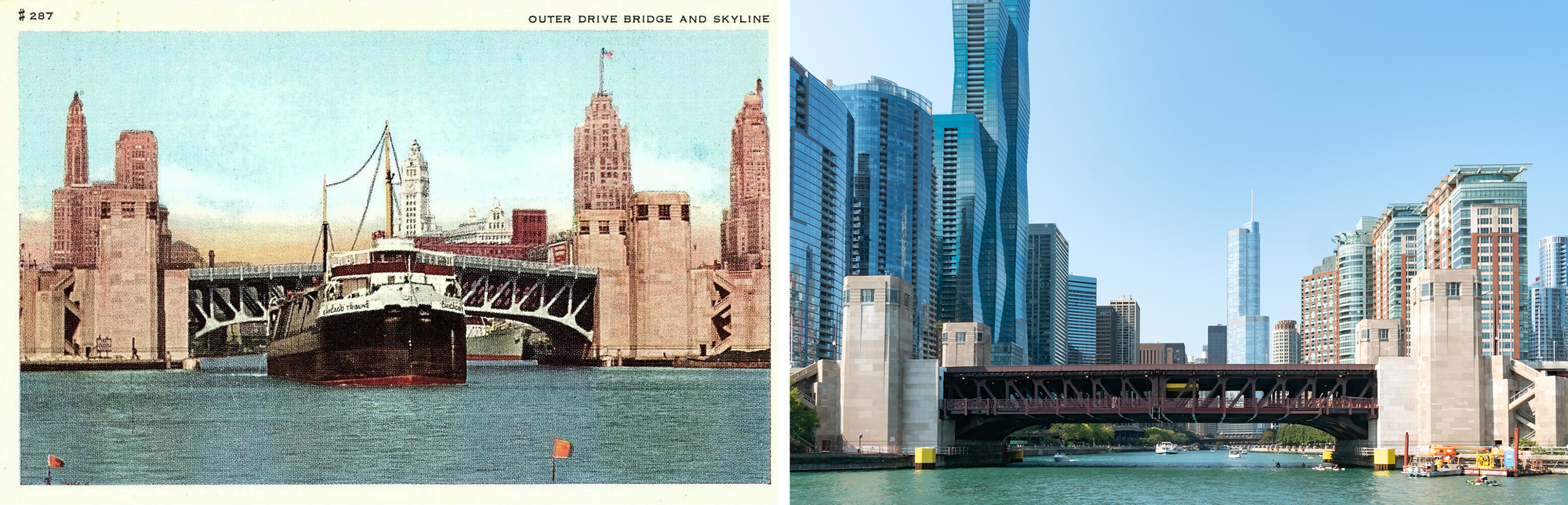

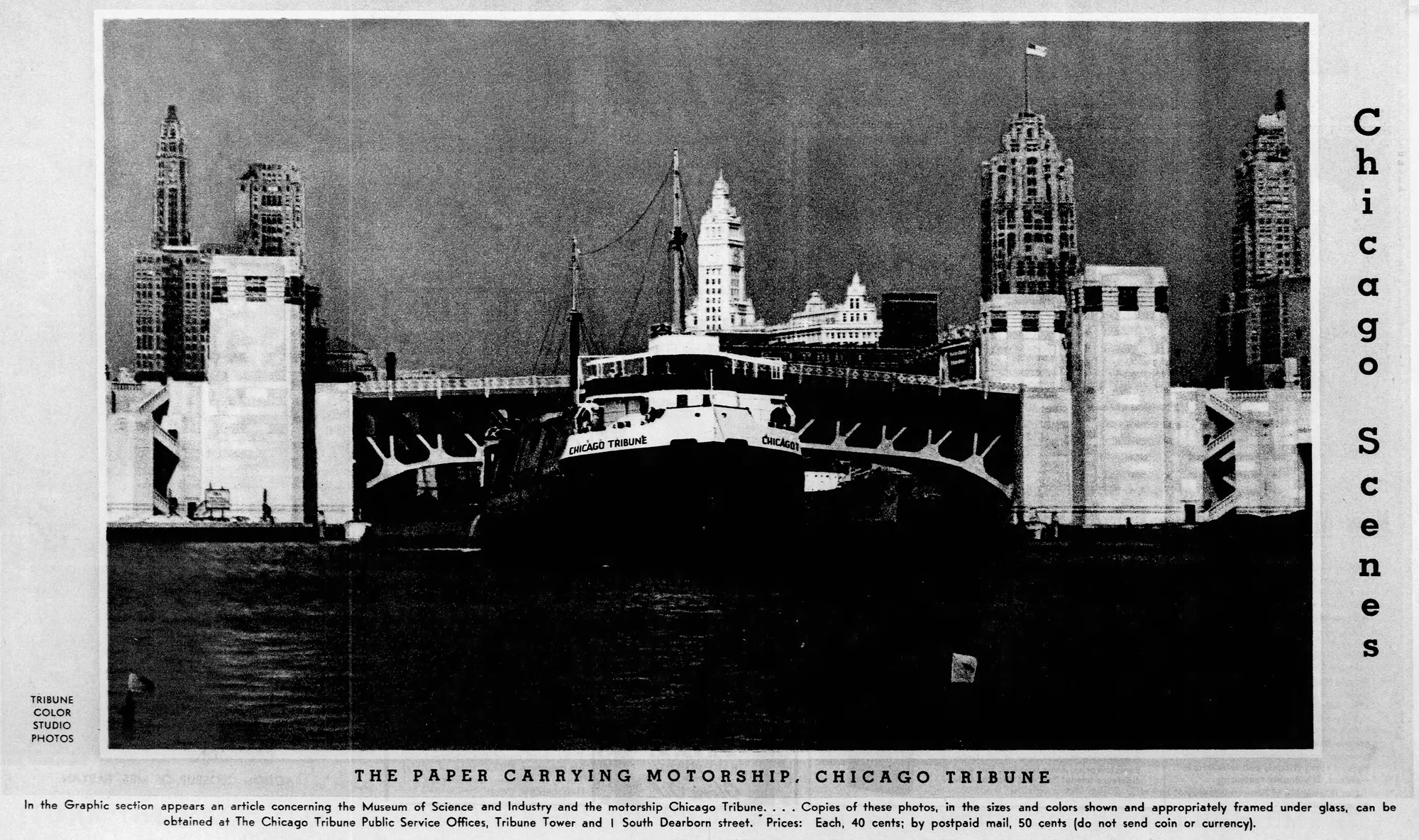

The monumental Outer Drive Bridge, only two years into its tenure carrying DuSable Lake Shore Drive over the Chicago River in this 1939 postcard, looks like it hasn’t aged a day, but Chicago’s brilliant crop of 1920s skyscrapers like Mather Tower, 333 N Michigan, the Wrigley Building, and Tribune Tower have all been completely hidden behind new towers like Studio Gang’s St. Regis, Mies van der Rohe’s Illinois Center, and the postmodern RiverView condos. There’s so much here I don’t know where to begin, so I’ll start wiiiiiiiiiiiiiith...

...the boat?

I was intrigued that you can make out the ship's name on the postcard, and it turns out the MS Chicago Tribune has an interesting story itself—a reminder that the Chicago Tribune was once a massive, vertically-integrated newspaper and the Chicago River a busy commercial waterway.

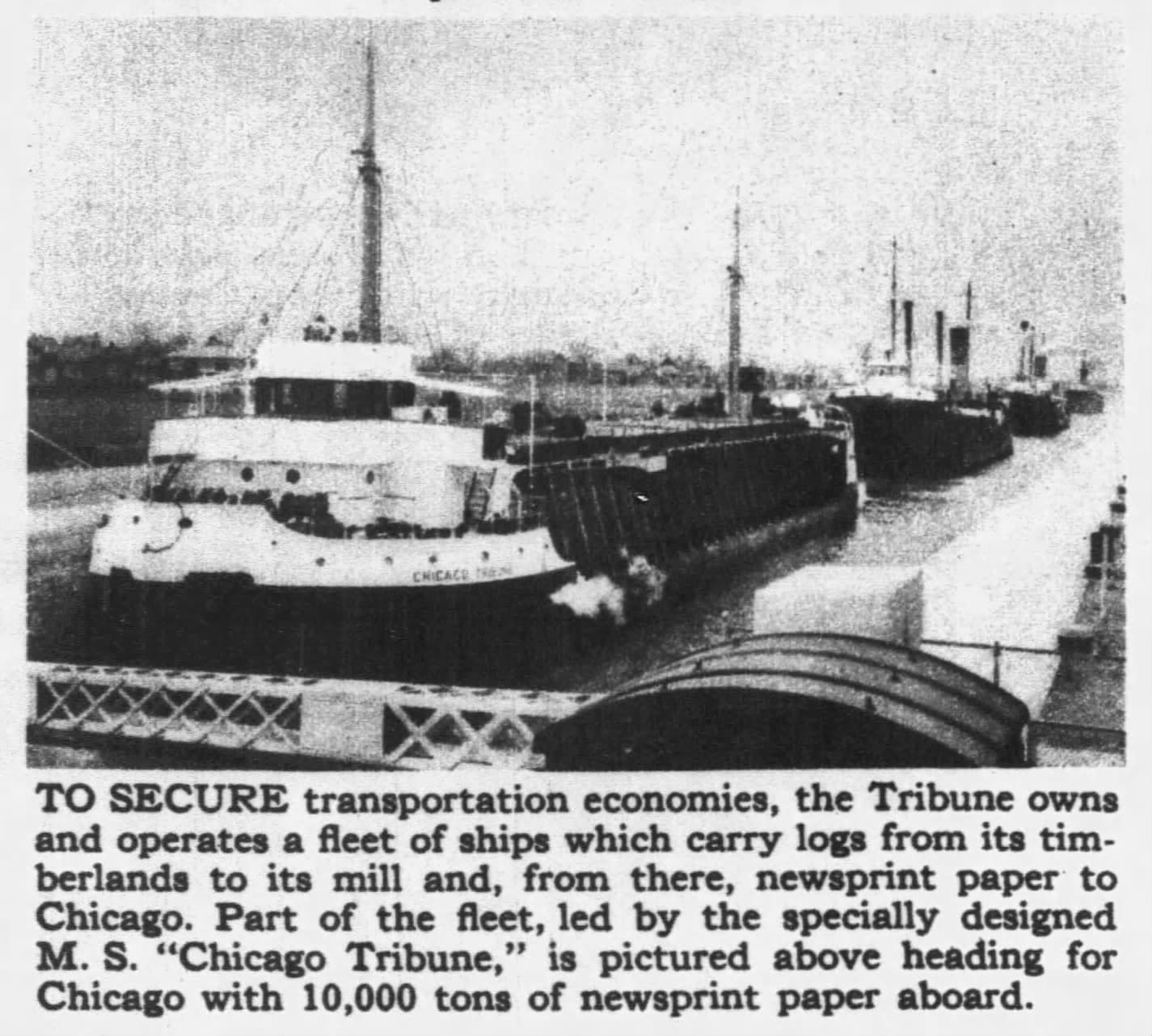

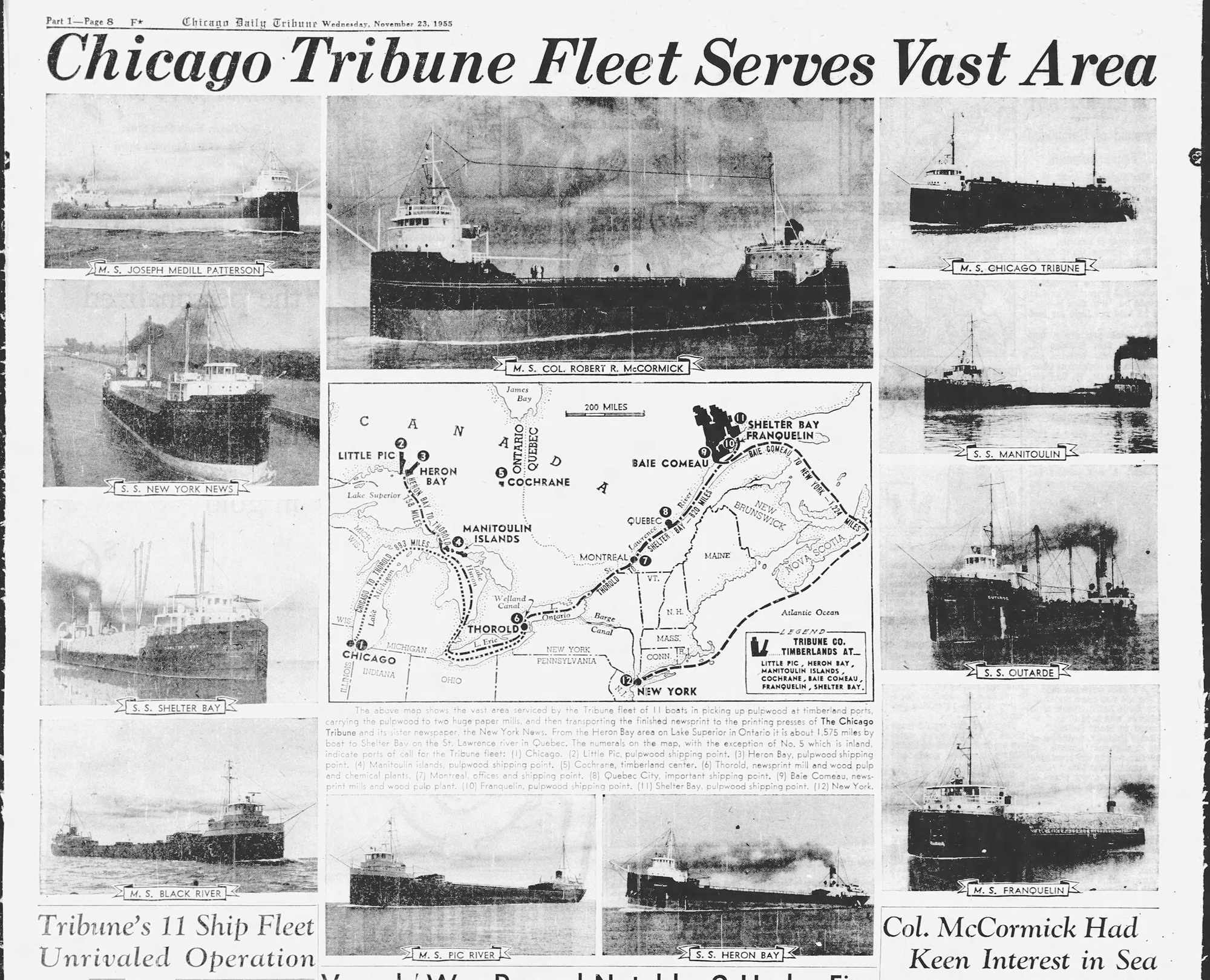

Vertical integration in the Tribune’s case meant pulpwood timber companies, sawmilling towns, paper mills, and—most relevant here—the shipping company that operated the lake freighters and canallers that moved all that pulpwood and newsprint around.

The Ontario Paper Company was the first piece of that integration puzzle for the Tribune in 1912. That year, the Trib's subsidiary built a paper mill in the town of Thorold on the Welland Canal, which had easy shipping access and cheap hydroelectricity from Niagara Falls. With the establishment of the Ontario Paper Company, the Chicago Tribune became one of a handful of US newspapers who controlled their own paper supplies.

However, the Thorold mill was far from the company’s timber limits on the St Lawrence River and the actual printing plants in Chicago (and later, in New York, for the Daily News), so two years later the company founded the Quebec & Ontario Transportation Company to integrate their pulpwood and newsprint shipping operations.

At first, the Q&O mainly served as pricing leverage for the Tribune Company. They were moving so much paper and timber that even with the establishment of a wholly-owned transportation subsidiary, they still needed to contract with outside lake freight as well as the railroad companies—the existence of the Q&O helped the company force those rates down.

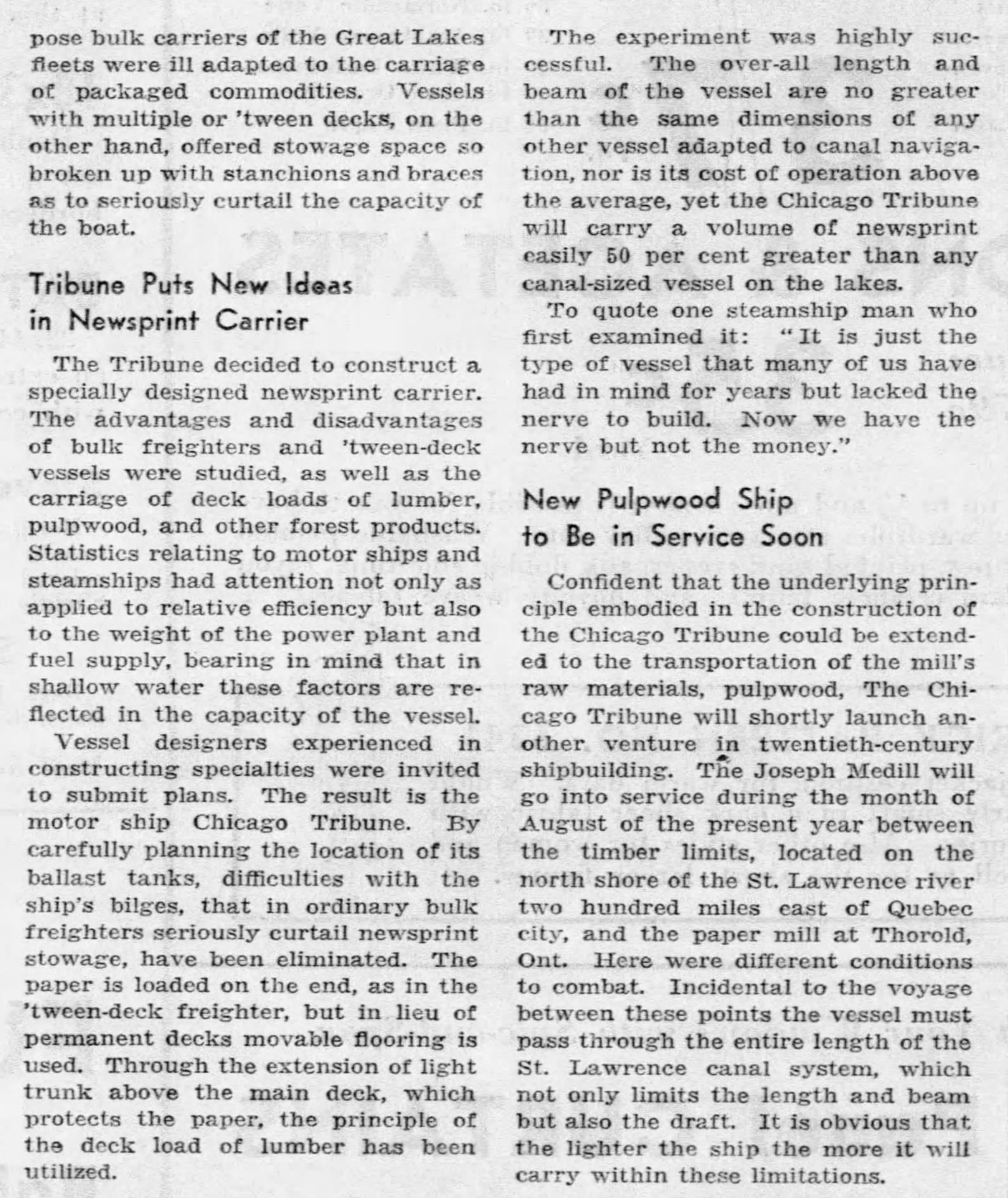

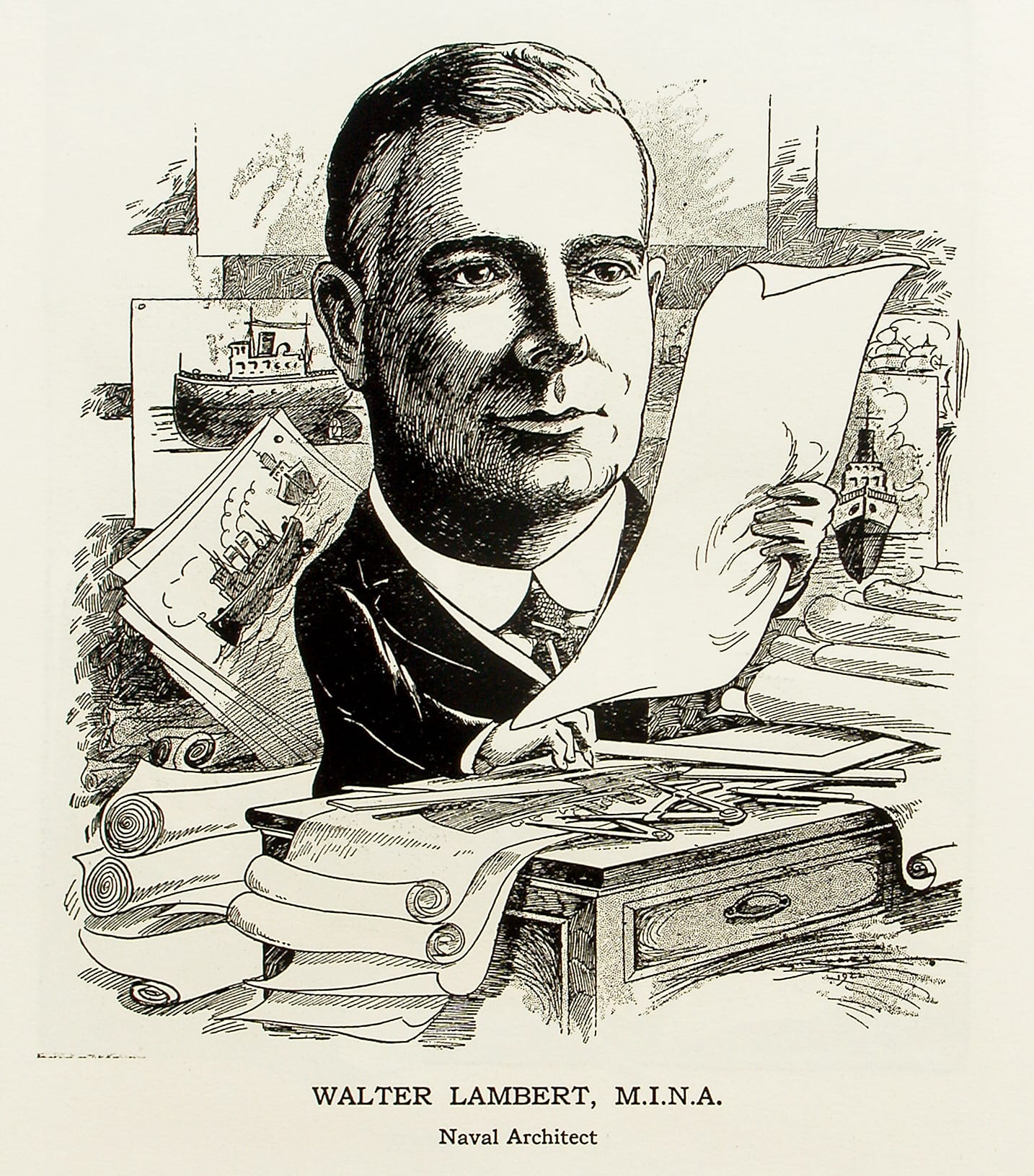

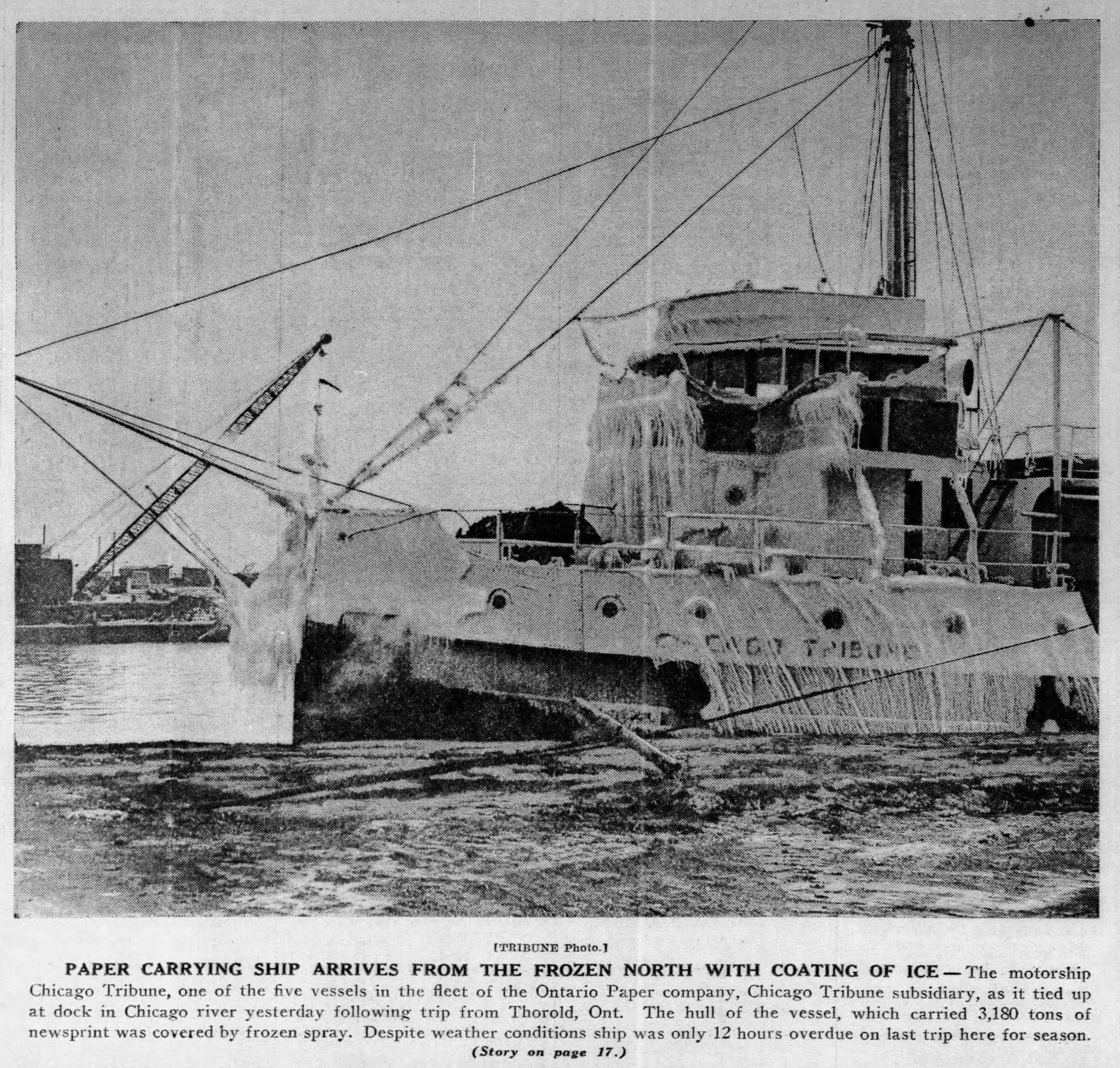

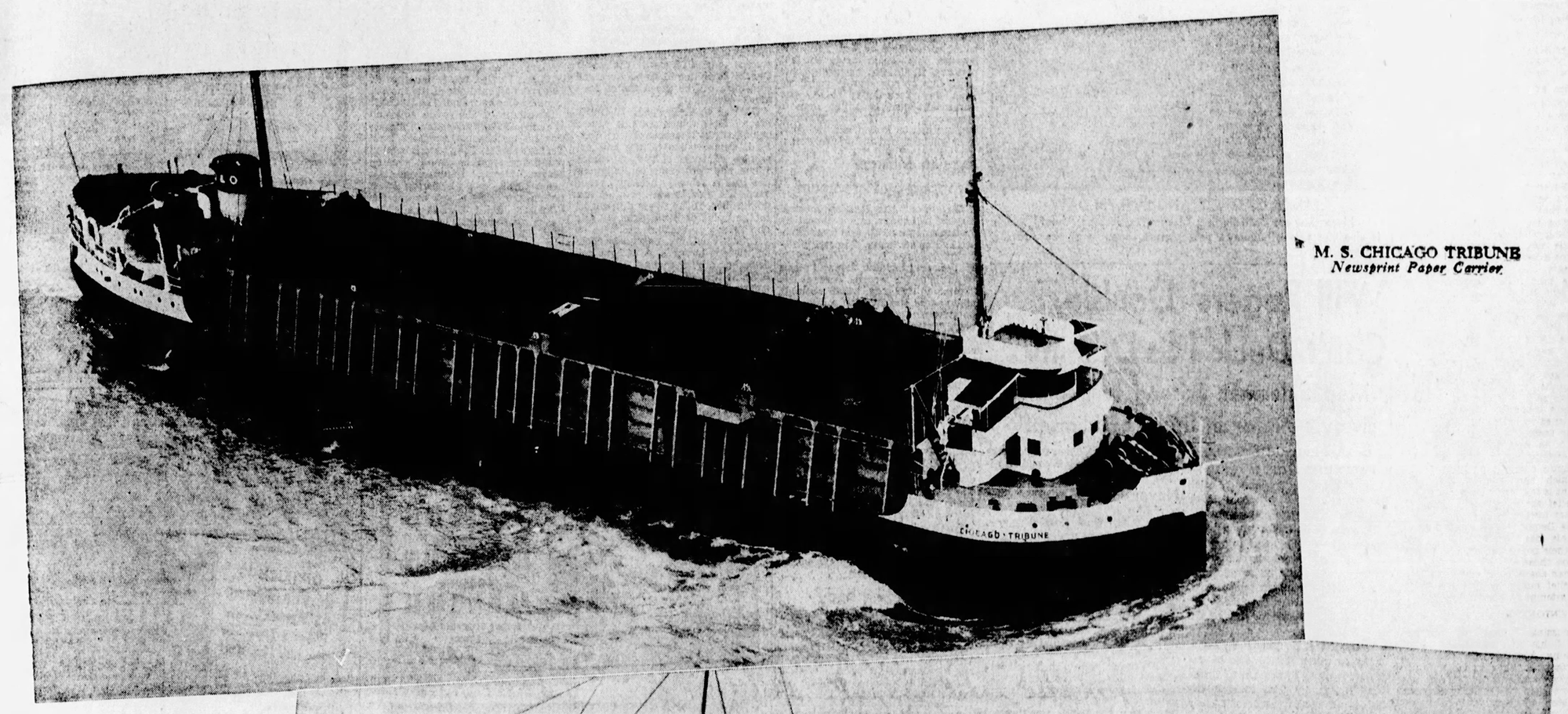

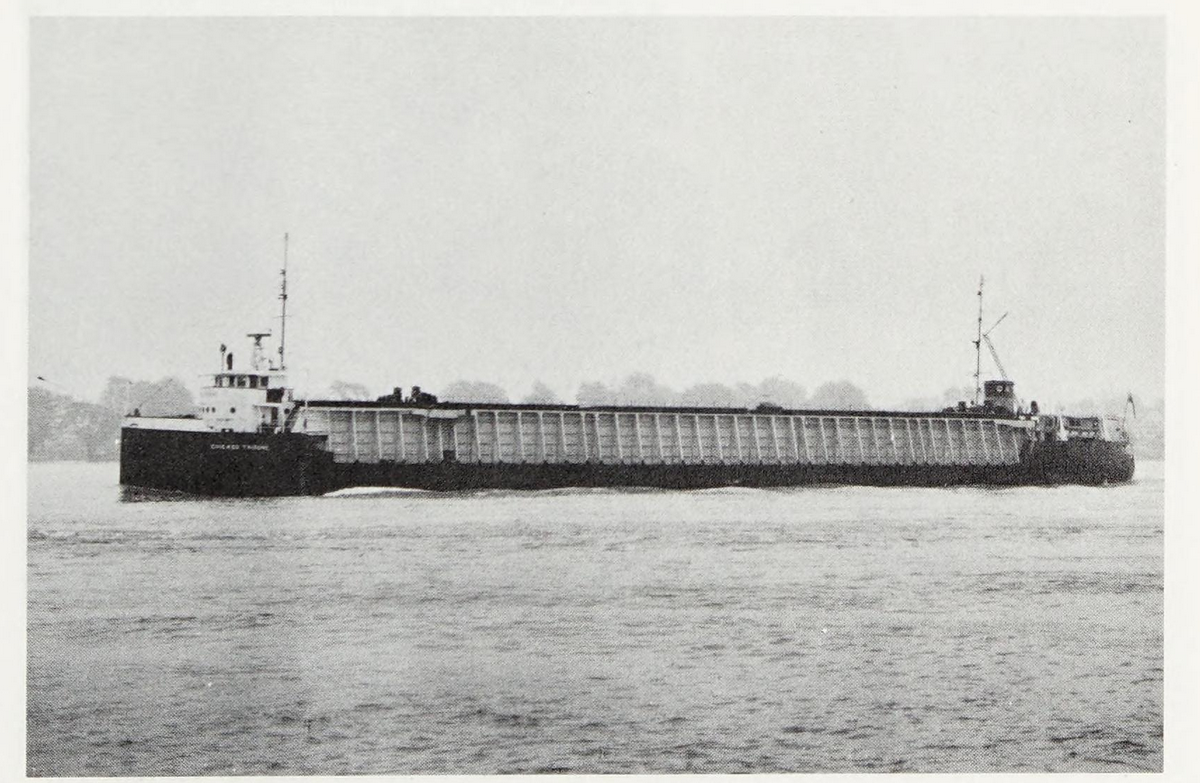

It was the MS Chicago Tribune that changed the game for the Q&O. Built in the British city of Hull and launched in 1930 as the Thorold, the ship was the one of the first of its kind. Montreal naval architect Walter Lambert and the Tribune Company specifically designed the ship around the needs of transporting massive rolls of newsprint, as well as the idiosyncratic needs of the route it would ply—no longer than 253 feet (to fit through the Welland Canal locks), with a maximum draft of 18 feet, diesel-powered, and able to transport 3,000 tons of newsprint at a time.

1935 article on ship design | 1922 photoengraving of naval architect Walter Lambert, McCord Stewart Museum | 1937 article | 1937 newspaper photo of the ship covered in ice | 1937 newspaper photo | 1939 newspaper photo | undated photo

Shipping stopped every winter, so the Tribune Company and Ontario Paper invested in warehouses in Thorold that could store the winter crop of newsprint until the ice cleared and shipping restarted (although ice floes trapped the MS Chicago Tribune at least once). Securing revenue cargo for the return trip from Chicago to Ontario appears to have been a bit of a challenge, especially for a specialist freighter like the MS Chicago Tribune, but it sometimes brought coal or grain back.

1937 promotional film, From Trees to Tribunes, the Internet Archive

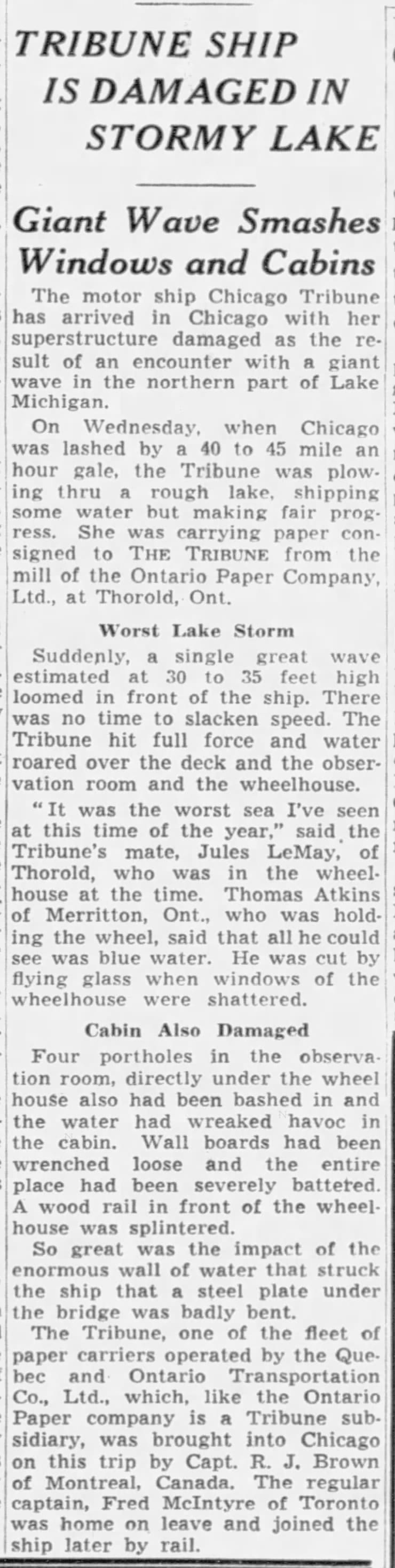

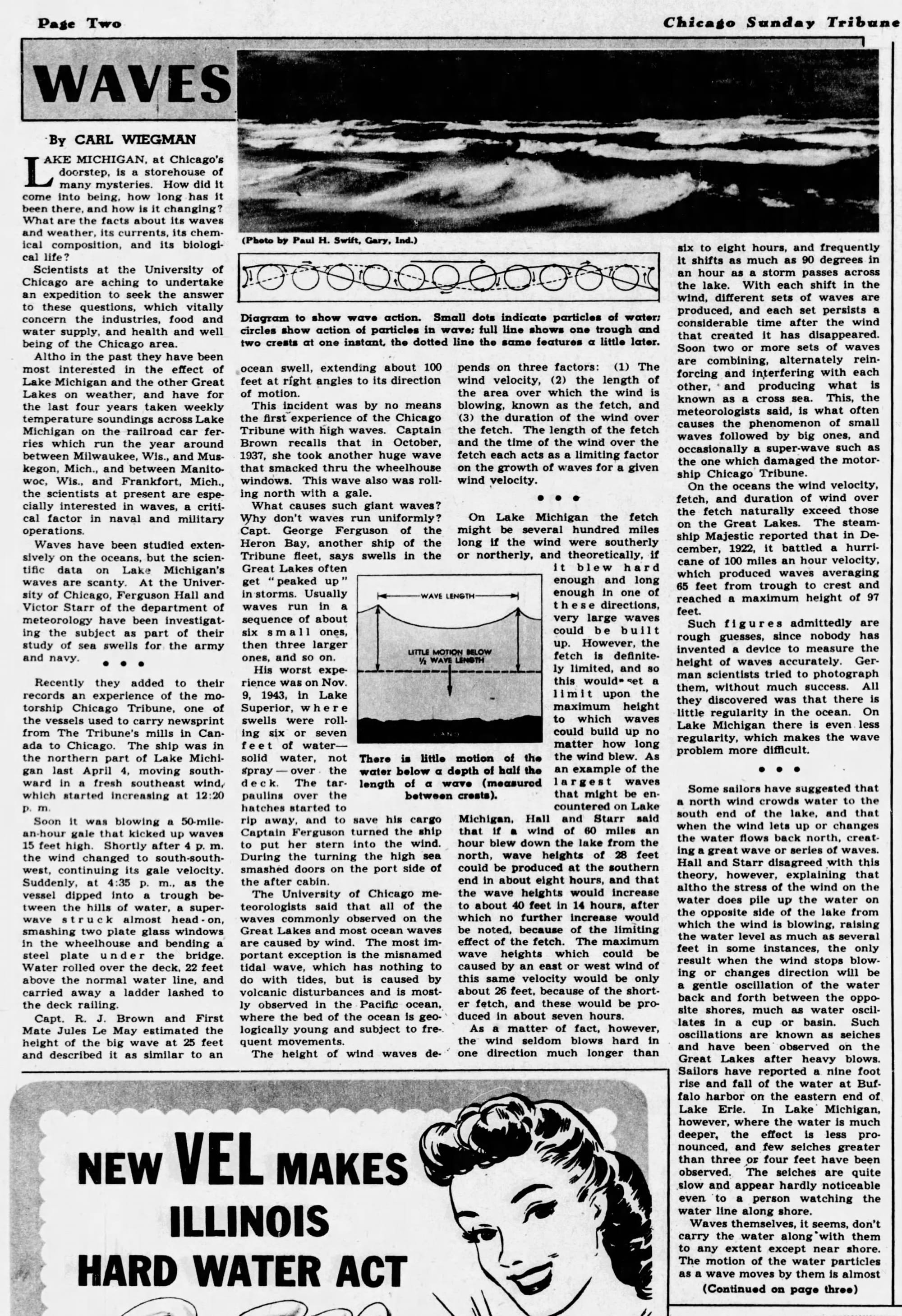

This was actually the second MS Chicago Tribune. The first, renamed the Thorold in 1933 when the Q&O rearranged the names of its fleet, was requisitioned by the Canadian government during WWII and sunk by the Luftwaffe in 1940. The MS Chicago Tribune (II) had an easier go of it, but the Great Lakes can be harsh too—a big wave blew out its windows during a gale in 1945, its hold caught fire in 1954, and it collided with another laker in the St. Clair River in 1960.

1936 article on the ship's grounding | 1939 article | 1942 article on coal back haul shipments | 1945 articles on the wave damage | 1952, Vintage Tribune | 1955 article on the Chicago Tribune fleet

At its peak in 1978, the Tribune Company had a fleet of 16 ships helping turn trees into tribunes. Foreshadowing the slow decline then rapid gutting of its namesake paper, Ontario Paper shut down the Quebec & Ontario Transportation Company in the early 1980s and sold its fleet in 1984. Within five years, the MS Chicago Tribune had been scrapped at Port Colborne, Ontario.

1965 article | Undated photo | early 1980s photo | 1985 photo via Industrial Scenery | 1987, Carlz Boats

The Tribune’s paper business lasted a bit longer—the company sold off their paper mill holdings in the early 1990s. The Chicago River remains a busy waterway, but the city's riverside printing plants have all been demolished—commercial traffic these days is more tour boat and bulk material barge than lake freighter.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Pulp & Paper Fleet: A History of the Quebec and Ontario. Transportation Company by Al Sykes and Skip Gilham

- Trees to News: a chronicle of the Ontario Paper Company's origin and development by Carl Wiegman

- Dead Tree Media: Manufacturing the Newspaper in Twentieth-Century North America by Michael Stamm

- Bunch of great photos of the MS Chicago Tribune on Shiphotos

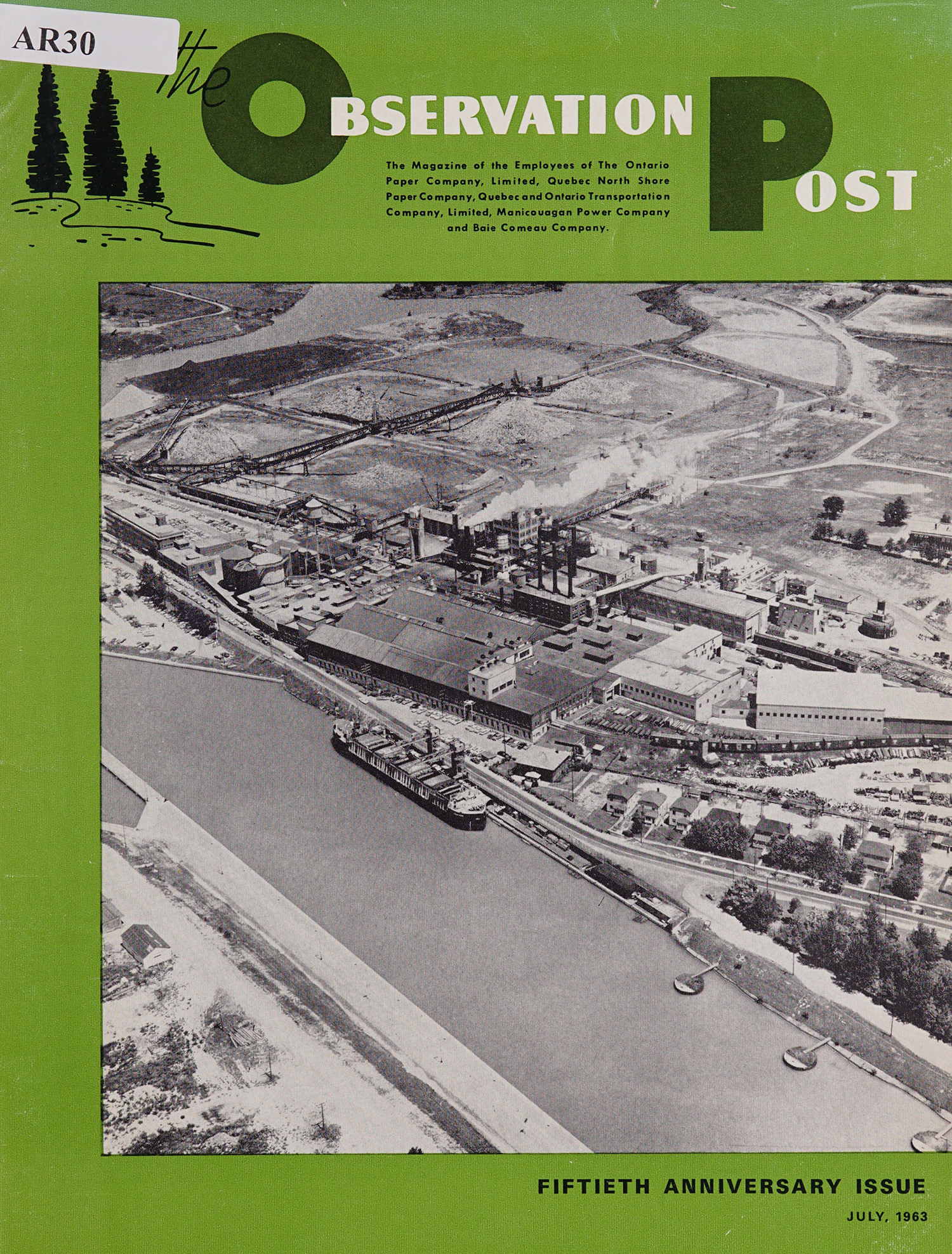

- The Observation Post, the 50th anniversary edition of the Ontario Paper Company employee magazine

- "'This Remarkable Growth': Investment in Canadian Great Lakes Shipping, 1900-1959" by M. Stephen Salmon

- Some urbex photos from the Thorold paper mill before it was demolished

Some neat late 1970s photos of the ship.

A 1945 article examining the wave mechanics on Lake Michigan that lead to the big wave that blew out the windows of the MS Chicago Tribune.

Member discussion: