A powerful work of utilitarian architecture, a pioneering use of reinforced concrete and a postcard featuring a never-built tower–this is a good one. Chicago’s old Montgomery Ward Catalog House is a potent symbol of industrial and labor history, connecting warehouse workers fulfilling orders for the US’ oldest mail order company to frazzled Millennials working their first post-grad office job at Groupon.

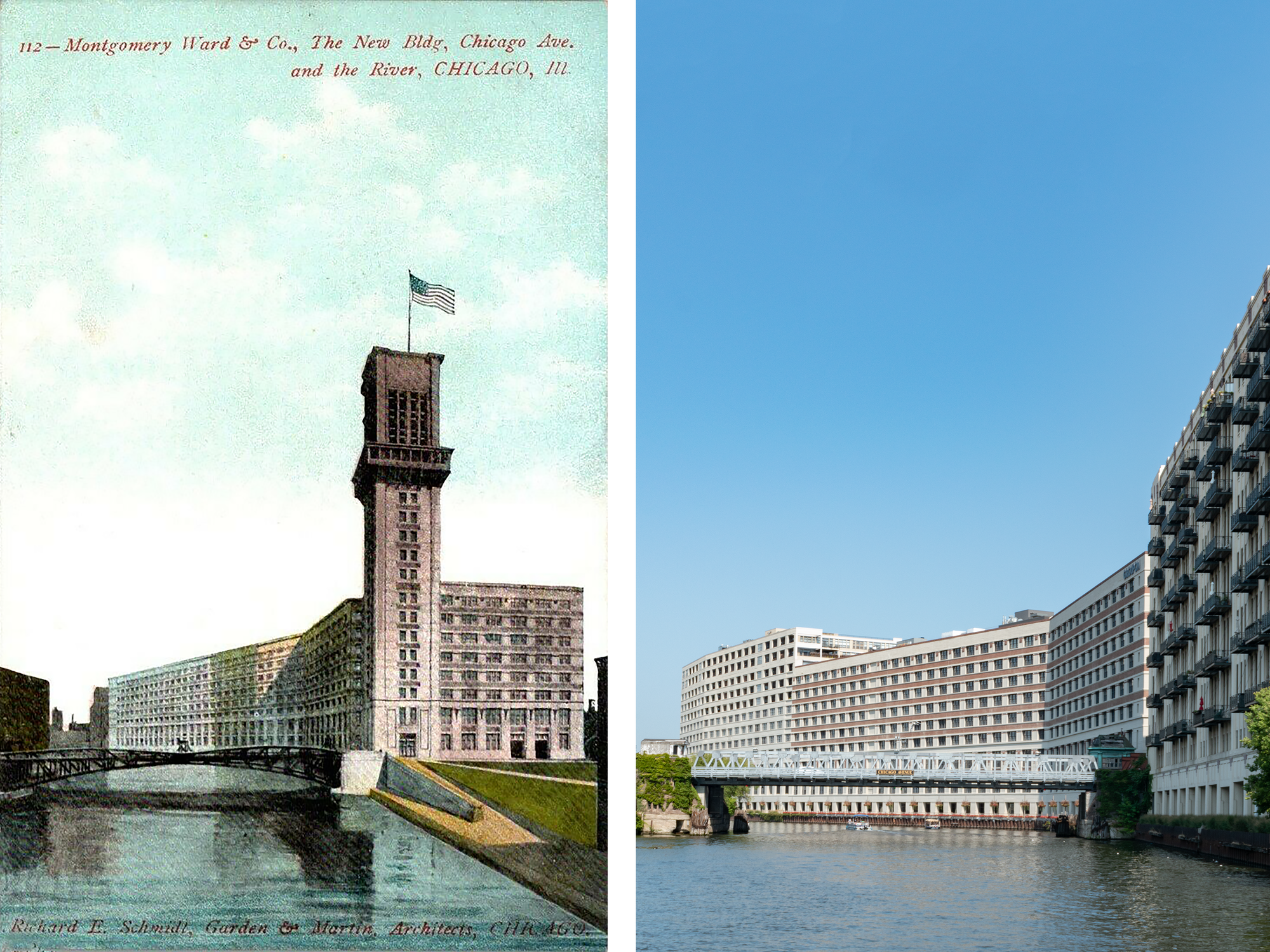

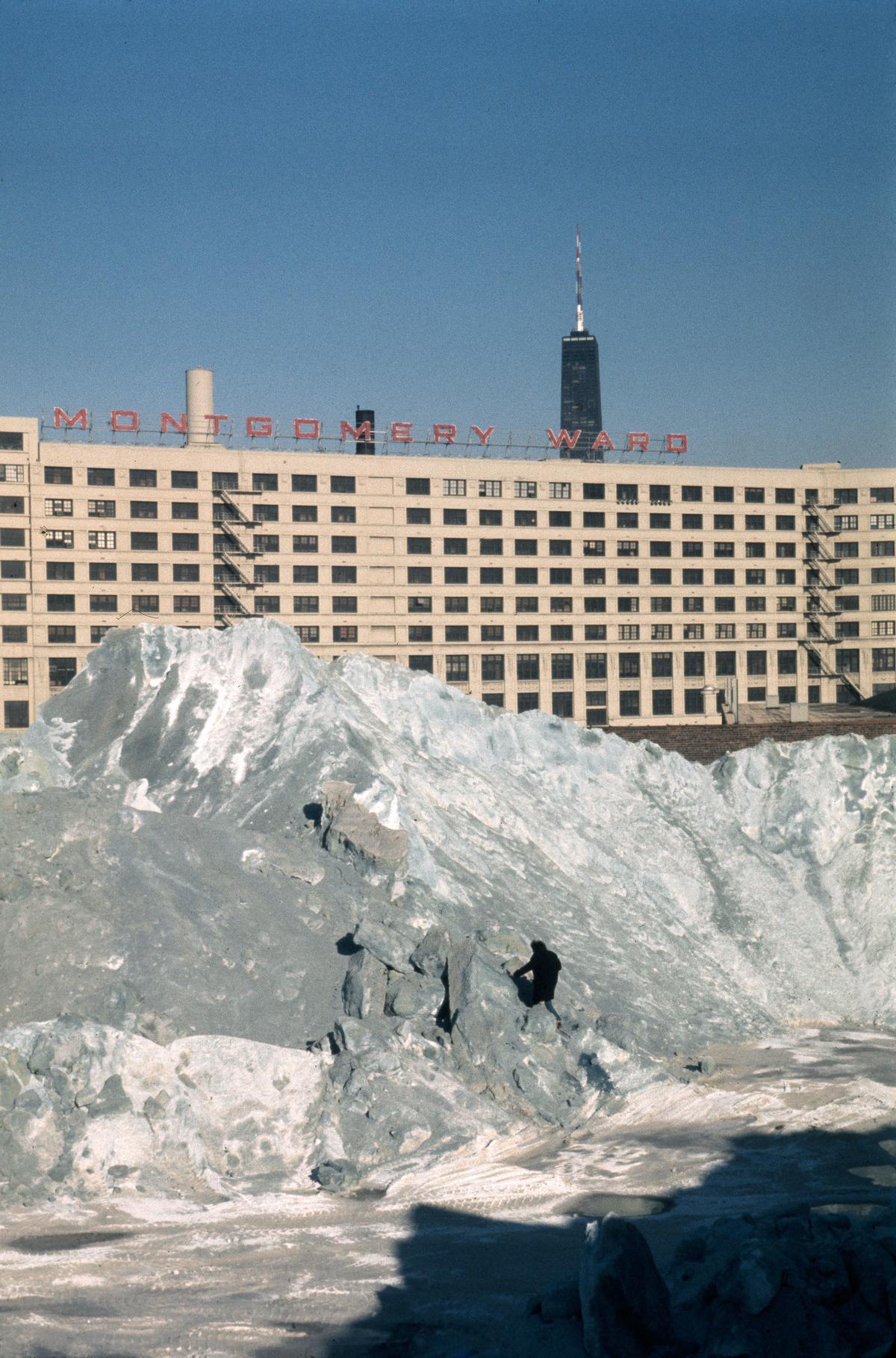

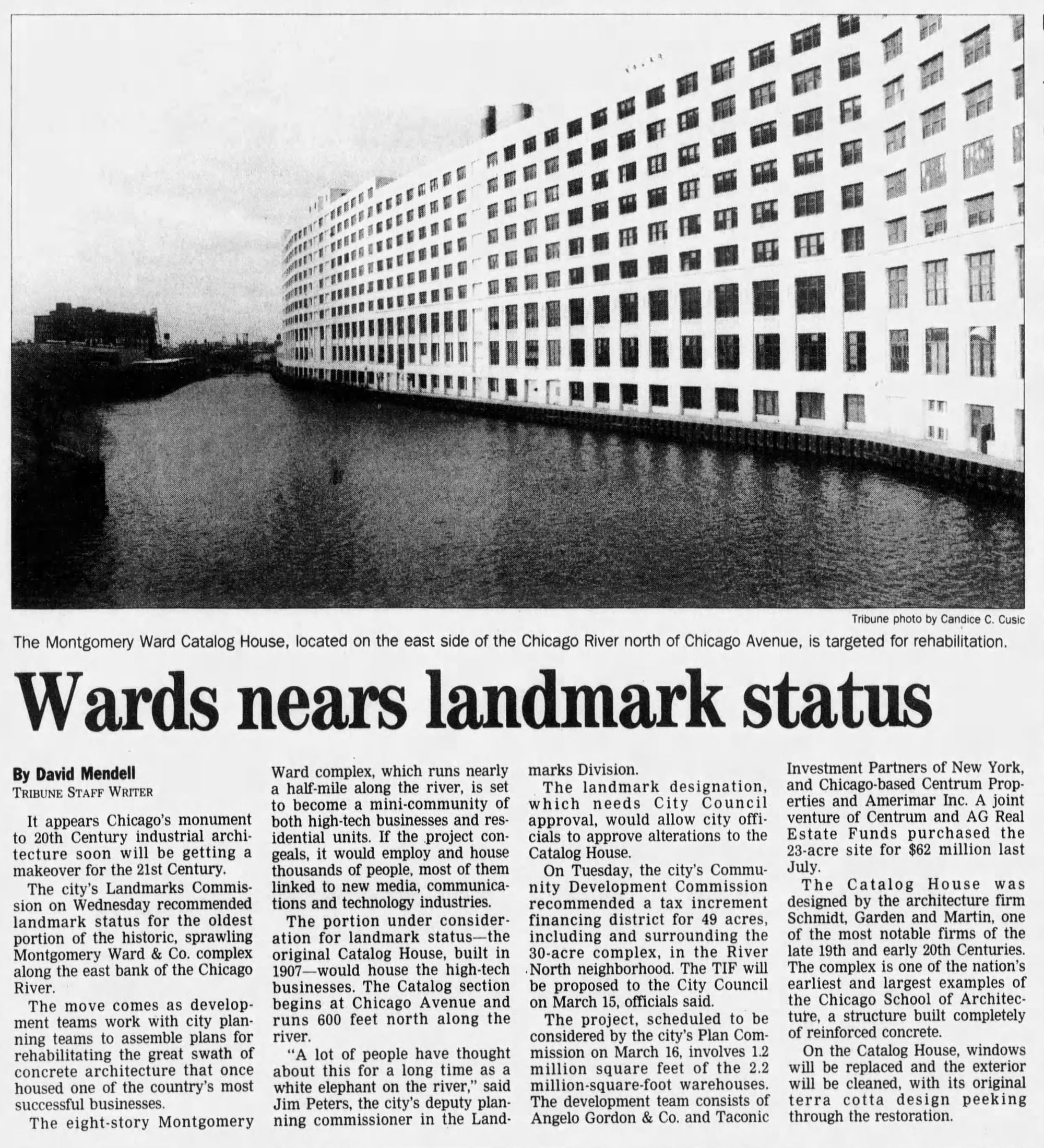

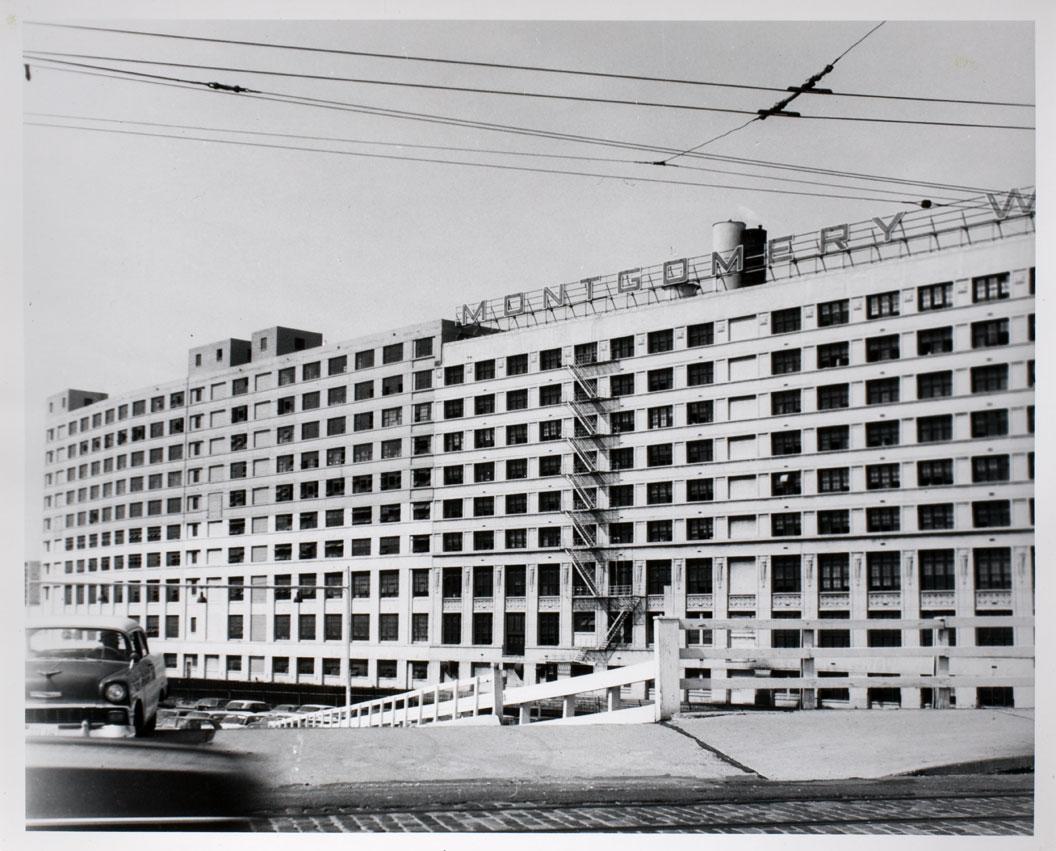

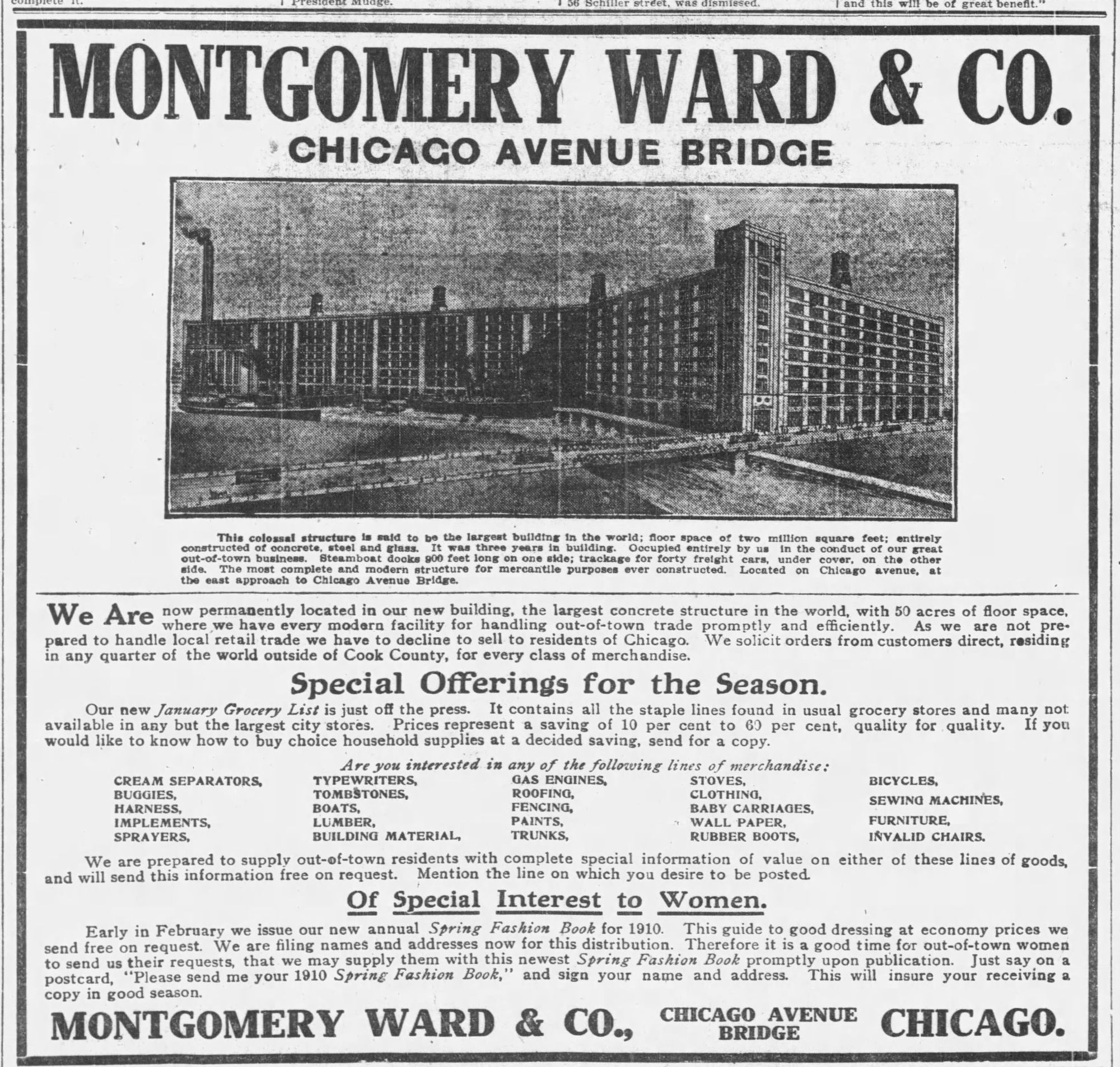

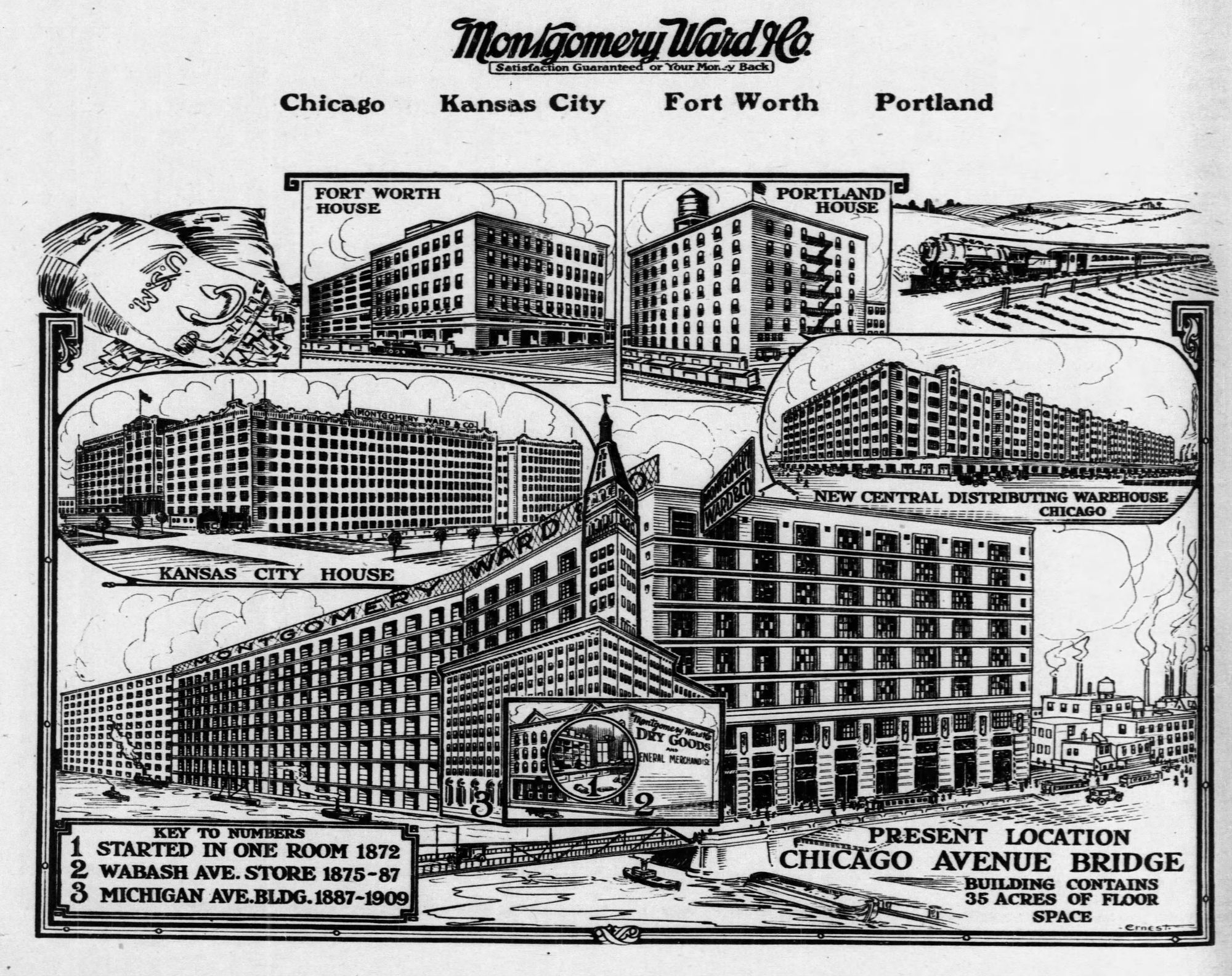

Finished in 1909 and designed by Schmidt, Garden, & Martin, critic Carl Condit said this was “one of the most powerful works of utilitarian architecture that our building art has produced”. It was the largest reinforced concrete building in the world when completed, and Hugh Garden’s design accentuated the building’s monumental horizontality, drawing the eye along the length of the building as it follows the bend in the river. Not everyone appreciated its immense size–an article in Architectural Record in 1908 described it as “a monotony truly appalling”.

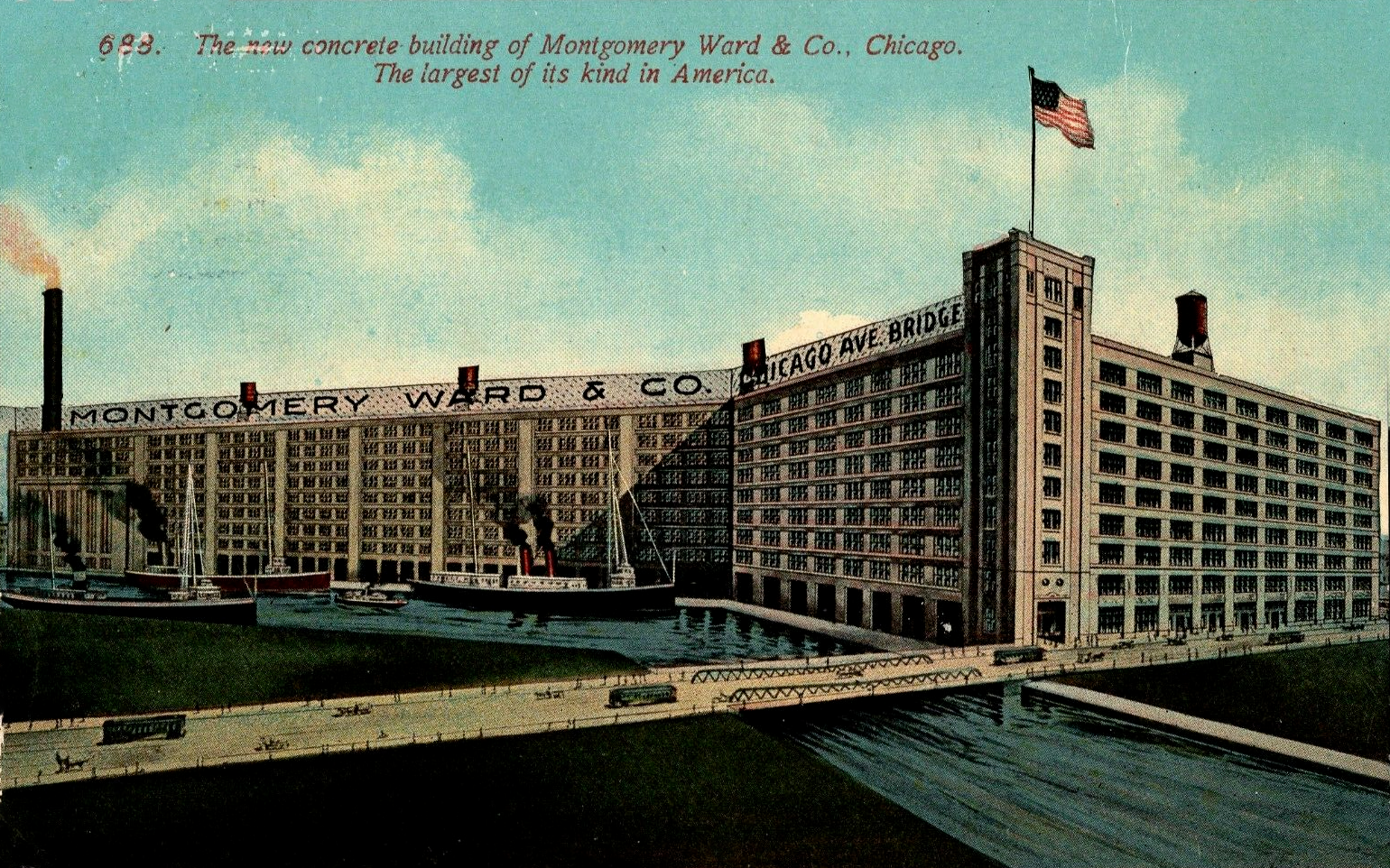

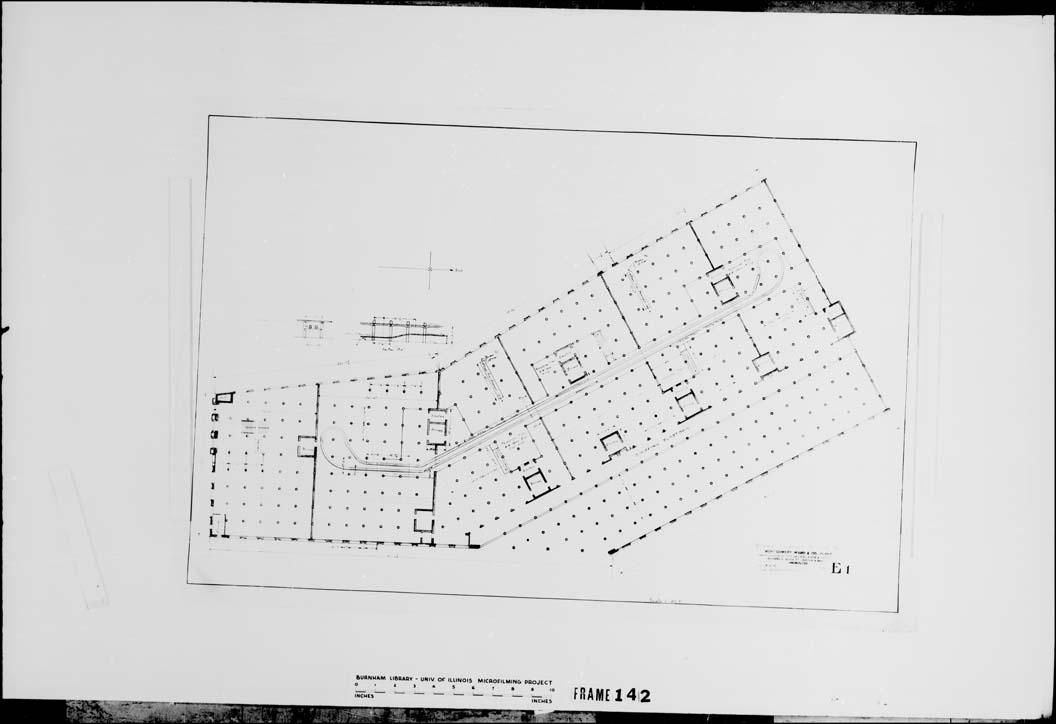

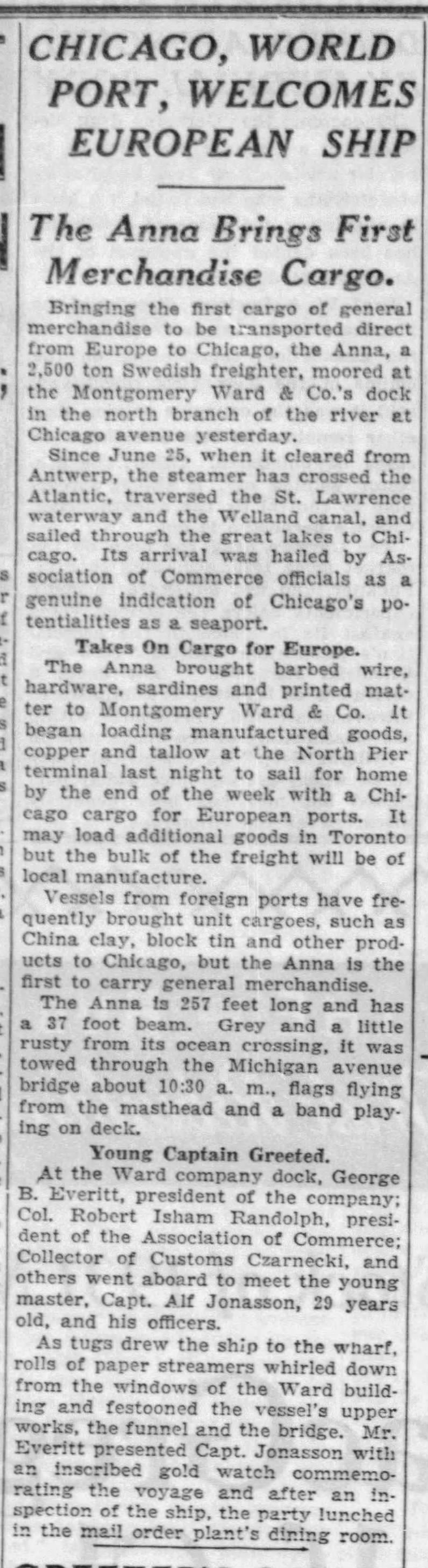

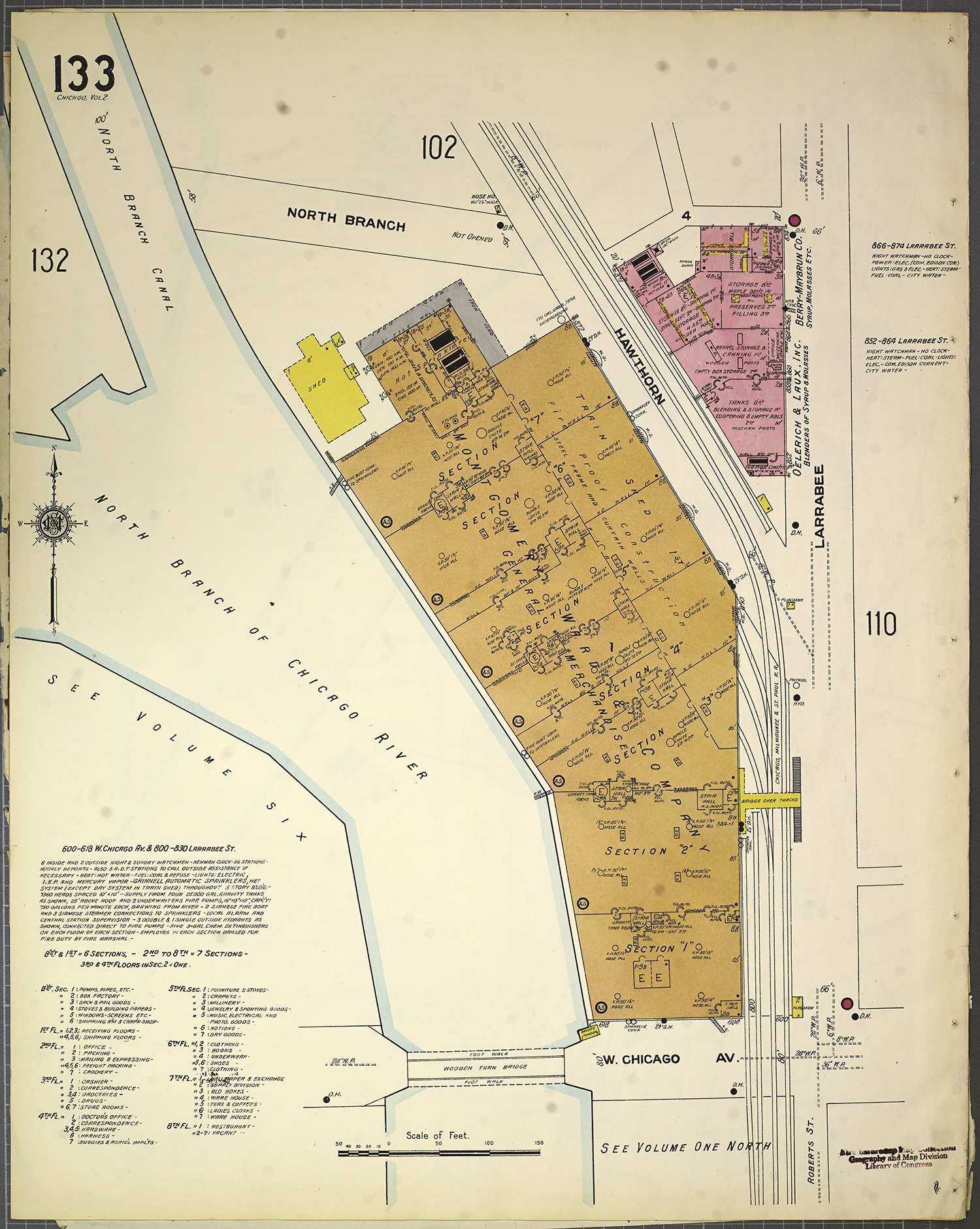

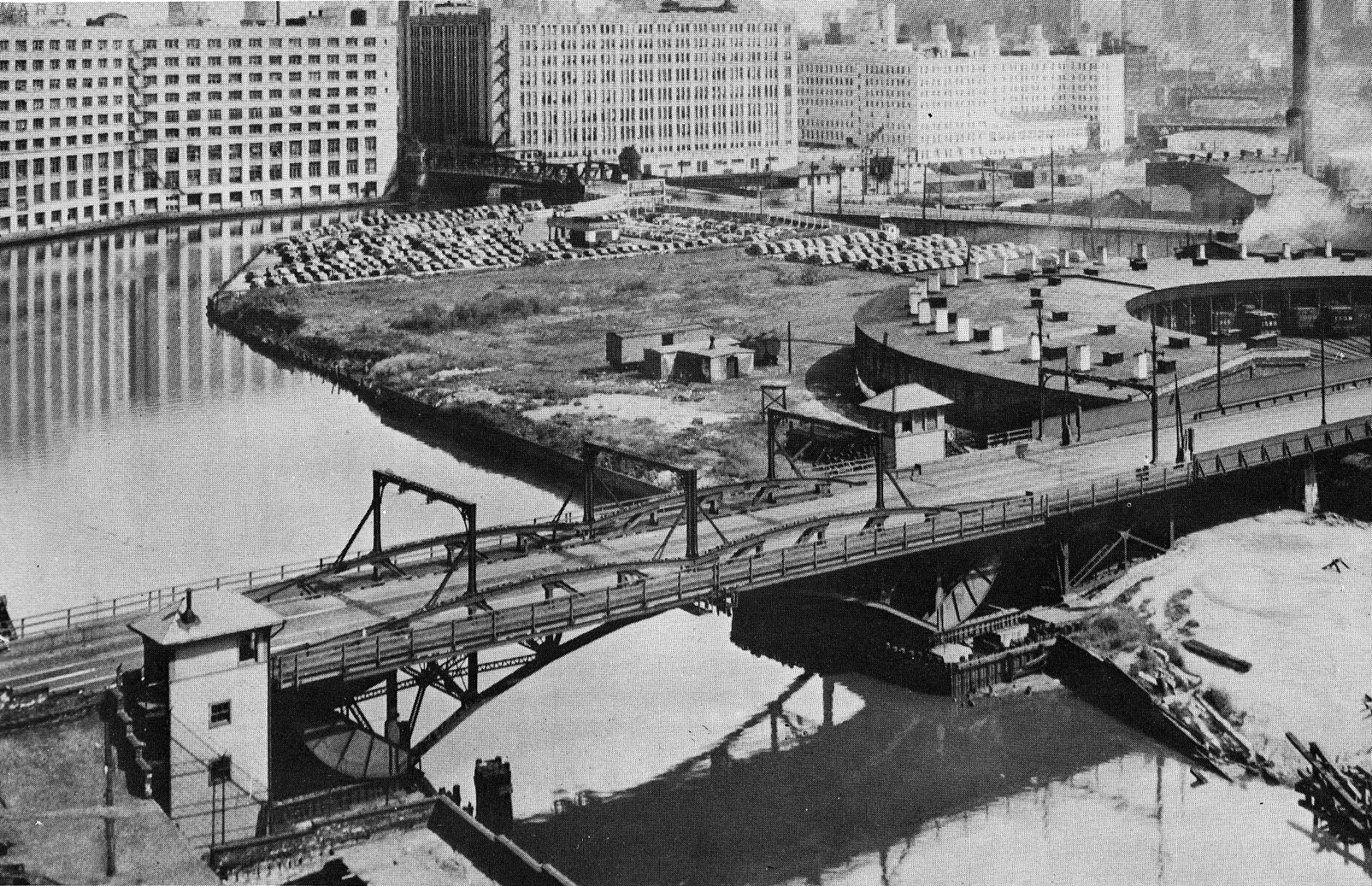

Montgomery Ward & Co., migrating north from their tower on Michigan Avenue, moved to this site for its access to the river and freight rail. The building had a steamboat dock that ran its full length, a first floor railshed that could accommodate 24 freight cars, and miles of internal conveyor belts to move goods around. Serving as the brains and circulatory system of Montgomery Ward’s mail order business, the first two floors had administration and executive offices, with the rest used as warehouse space. To communicate that the programming of the lower floors differed from those above, Garden ornamented them with organic terracotta forms–elements that we’d describe as Sullivanesque today, but Garden (kinda relatably, tbh) preferred to call “Gardenesque”.

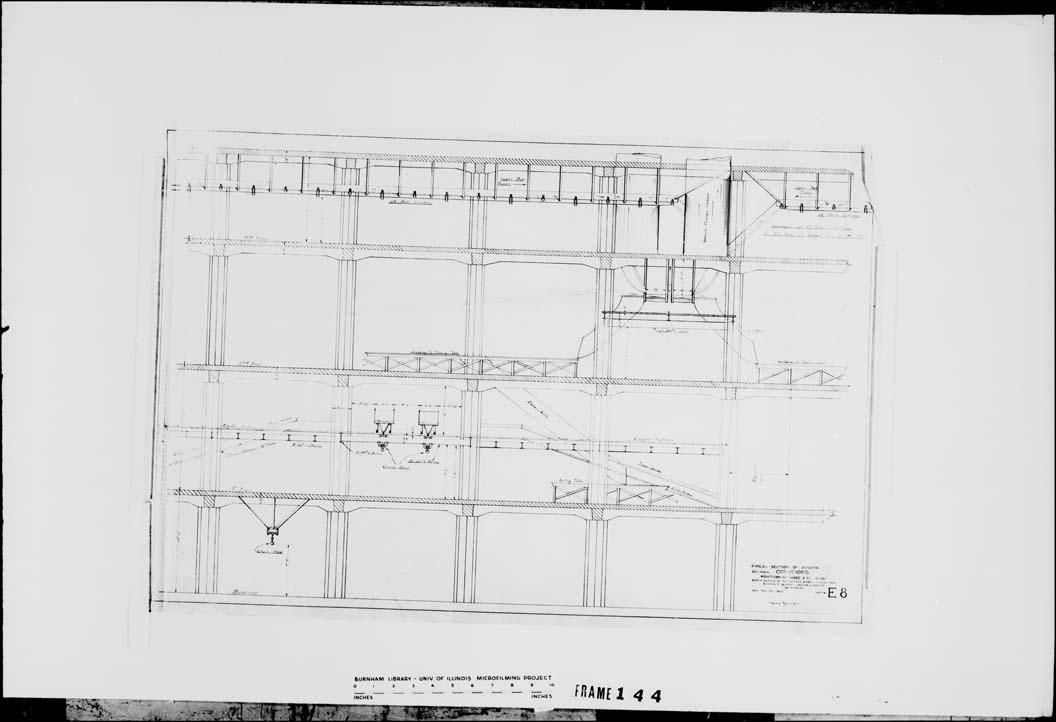

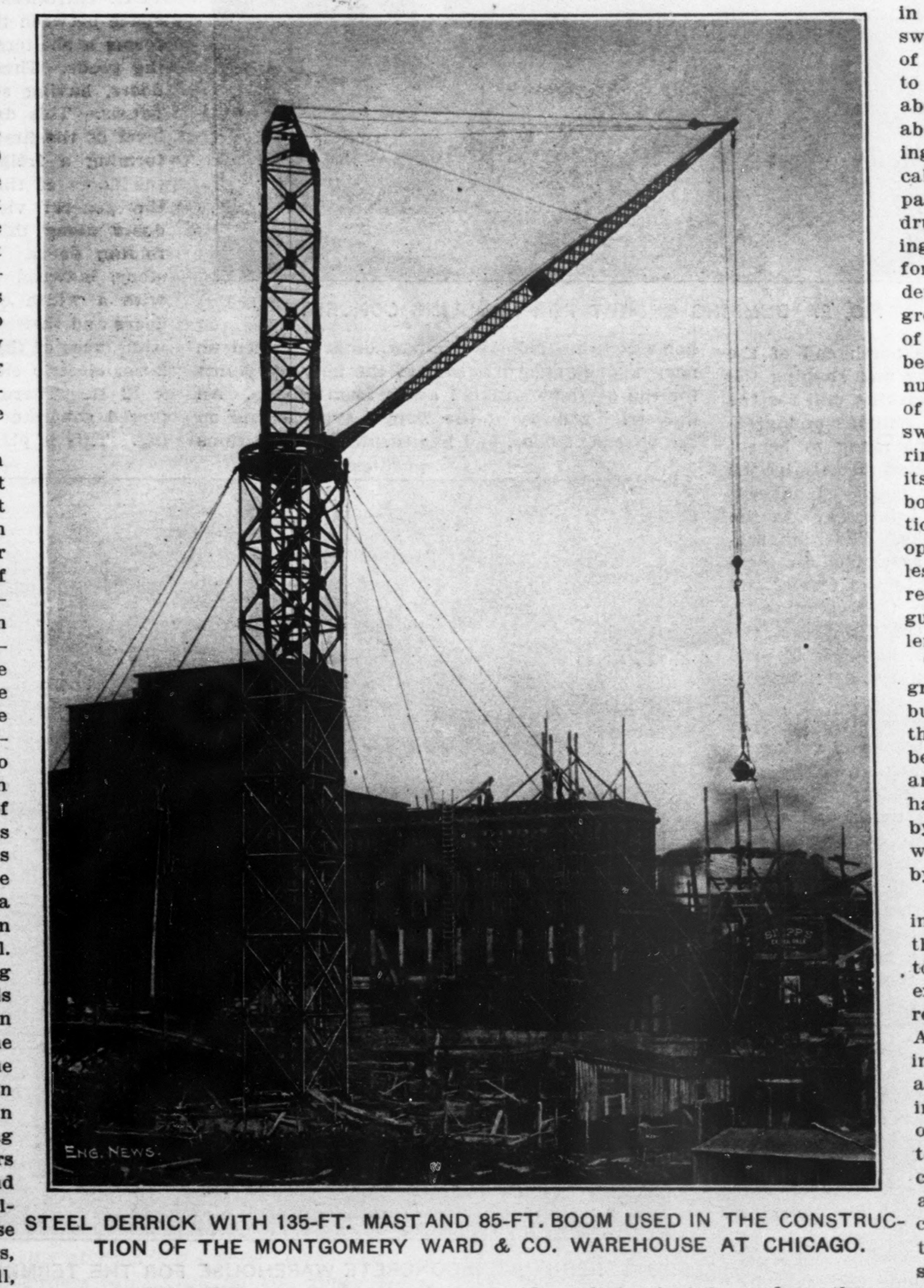

When it was pulled in 1906, the building permit was the most expensive in Chicago history, but construction was stop-start. First off, reinforced concrete was a relatively new construction material, and it hadn’t really been used at this scale before–the builders put together a system where concrete mixing plants on site filled special dumping buckets, which were then moved via narrow-gauge rail to steel derricks that hoisted the dumping buckets to pour the concrete.

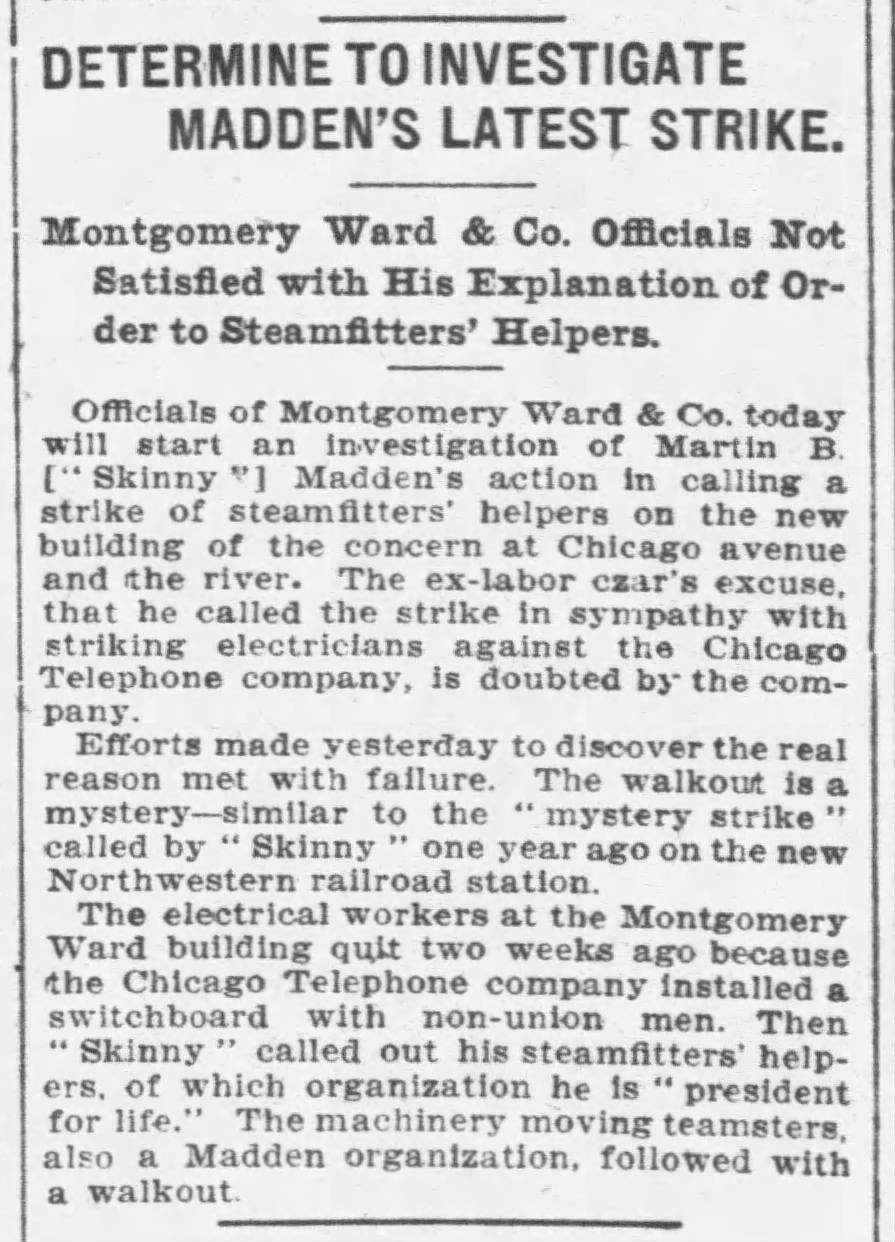

There was also labor strife: a carpenter’s union strike, an ironworker’s strike, a pipefitters sympathy strike (did you know sympathy strikes–where workers in another union or industry engage in a solidarity action to support striking workers–were outlawed in the US by the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947? Part of the systematic, multi-pronged assault on worker power after the New Deal.). Construction actually stopped at five stories during the Panic of 1907. Ward’s started using the incomplete building, but there were doubts whether they’d ever complete it to the planned eight stories, until construction on the final three floors recommenced in 1909. The tower in the postcard–likely planned to conceal a water tank–was never built.

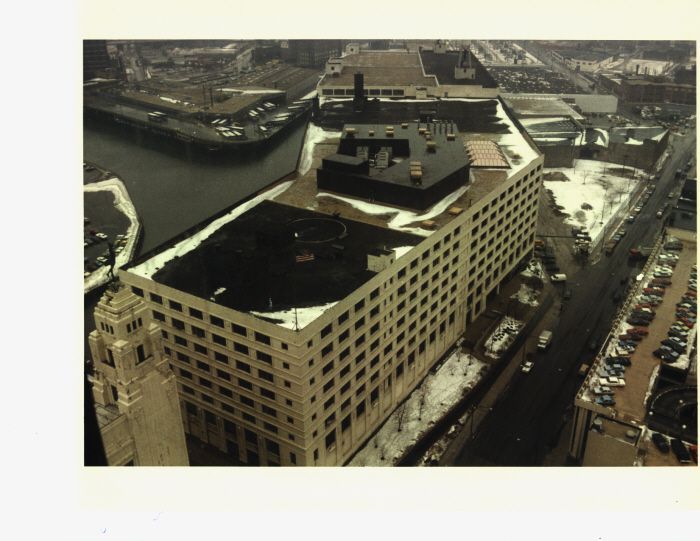

Ward’s constantly assembled more land to add to the building, and this riverside behemoth was expanded multiple times. Slowly crawling to the north over the decades, the most notable additions came in 1917 and 1939-1940, in both cases designed by the company’s in-house architectural and engineering department. The company’s office functions moved across the street to a new administration building in 1929.

Montgomery Ward & Co. beat Sears to the mail order game by twenty years–how did they squander their headstart and fumble the opportunity to get their ass beat by Walmart and Amazon? Well, a big chunk of blame belongs to the right-wing crank who moved into that administration building in the 1930s–Sewell Avery, chairman and president of Ward’s from 1931 until 1955.

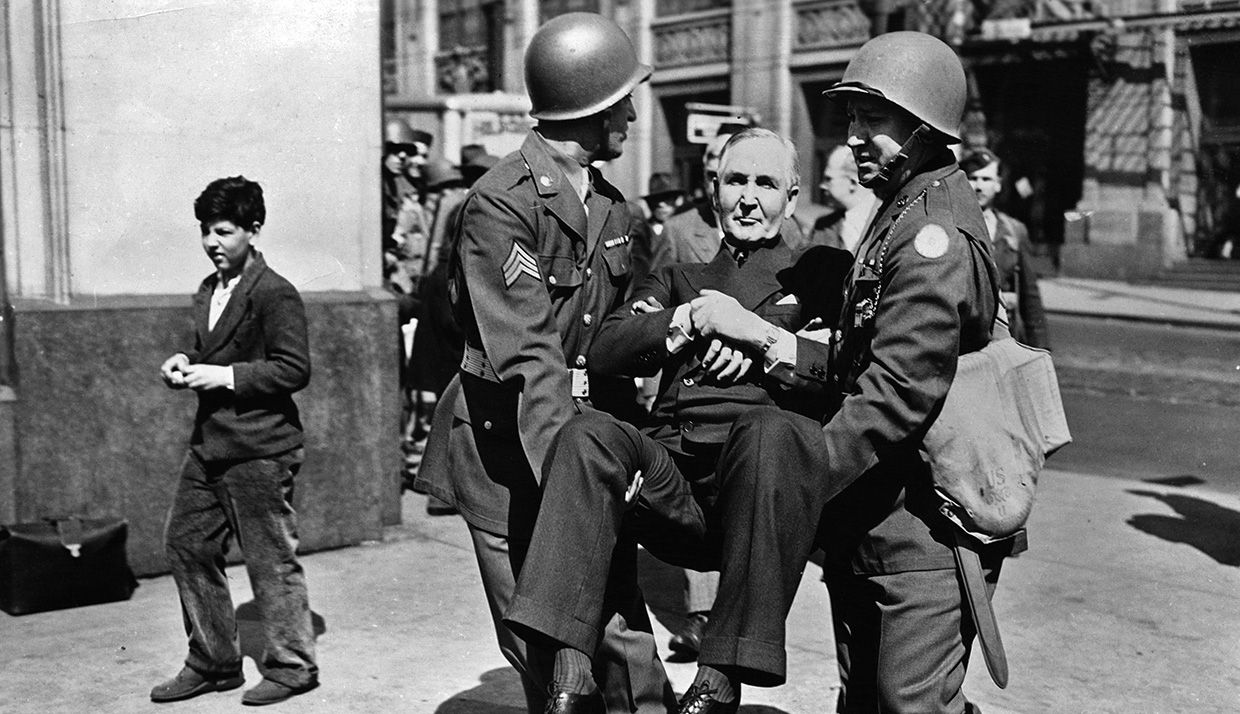

Brought in during the Great Depression, Avery turned the catalog company into a bonafide brick-and-mortar retailer and dragged it into profitability during the Great Depression…but his kooky political views soon started to damage the company. In the 1940s, Ward’s employees unionized, but Avery was so fanatically anti-labor that he refused to recognize the union and negotiate a contract for years. The impasse eventually brought a key part of the American economy to a standstill during wartime, so to ensure the flow of goods the federal government took over the company in 1944, literally carrying Avery out of the building (the chairman was so irrationally intransigent they actually took over the company twice). Avery’s attempted union-busting, his physical removal from the premises, and brief loss of control of the company was a theatrical sideshow to where his kooky views did actual lasting damage. Avery so madly opposed the New Deal that he convinced himself the country was destined for a second Great Depression after WWII ended…and so Avery made sure the company didn’t invest a cent in growth under his tenure, hoarding cash for lean times he was sure were around the corner. With Avery hanging on until 1956, Ward’s missed the postwar boom. The company spent the rest of its existence desperately trying to catch up to Sears, whose less-extremist leadership were able to adapt to real economic conditions, investing in suburban stores and building themselves a commanding lead in market share.

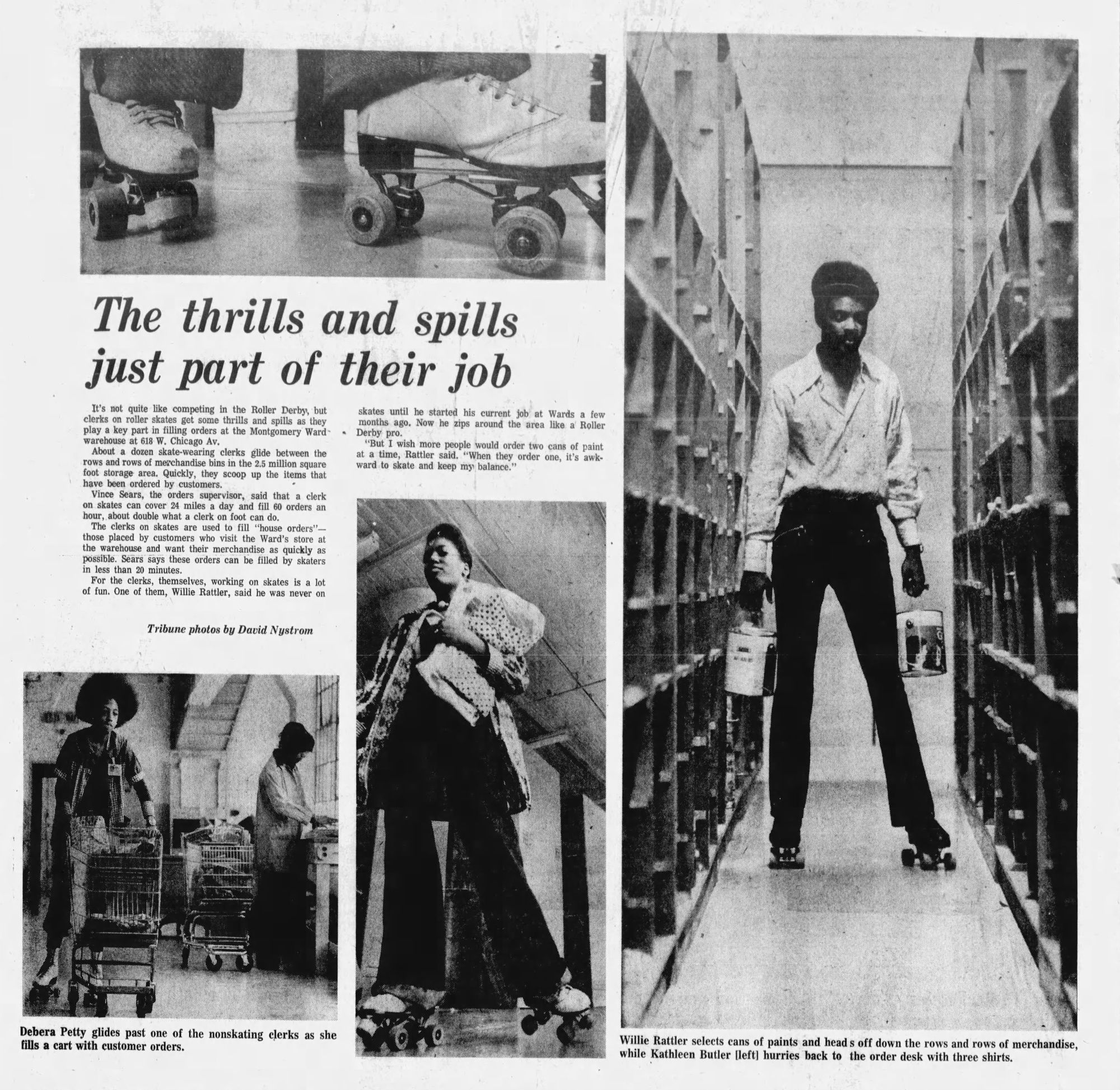

From the administration building, Ward’s eventually moved a few hundred feet down Chicago Avenue in 1972 to a skyscraper designed by Minoru Yamasaki. While the office work of the retail giant had moved elsewhere, pickers on roller skates continued to fill orders in the Catalog House through the 1970s (at least), and the building remained in the company’s hands until its second bankruptcy in 1999.

Designated a Chicago landmark in 1975 and National Historic Landmark in 1978, the development team who bought the building from Ward’s intended to convert the northern (newer) portion into condos and the southern portion into a mixed-use tech center. Initially branded as an “E-port”, the adaptive reuse here received a boatload of public money through a TIF deal. In exchange for $33m, the city received a public riverwalk and a couple hundred subsidized, affordable, and CHA units. Gensler did the adaptive reuse of the office and retail portion, and Pappageorge Haymes designed Domain, the condo conversion of the northern part of the building.

Positioned as a buzzy hub for Chicago’s tech community in the mid-2000s, Groupon opened their HQ in the building in 2008. An entire micro-generation of Chicagoans–that poor cohort who graduated into the Great Recession–has probably had a mental breakdown in this building while working for Groupon in the early 2010s. Renamed 600 W. Chicago, developer Sterling Bay scooped up the building for $510m in 2018.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Chicago Landmark Designation report

- National Register of Historic Places nomination form

- An extensive article on Hugh Garden in The Prairie School Review in 1966 (PDF)

- "An American Architecture" in Architectural Record in 1908, looking at Schmidt, Garden, & Martin's work

- A decent video on the downfall of Montgomery Ward's

- The TIF agreement that saw the City of Chicago spend $33m on the rehab of the building in the early 2000s

- A 1907 article in the Engineering News about the construction process

- In the Society of Architectural Historians Archipedia

Member discussion: