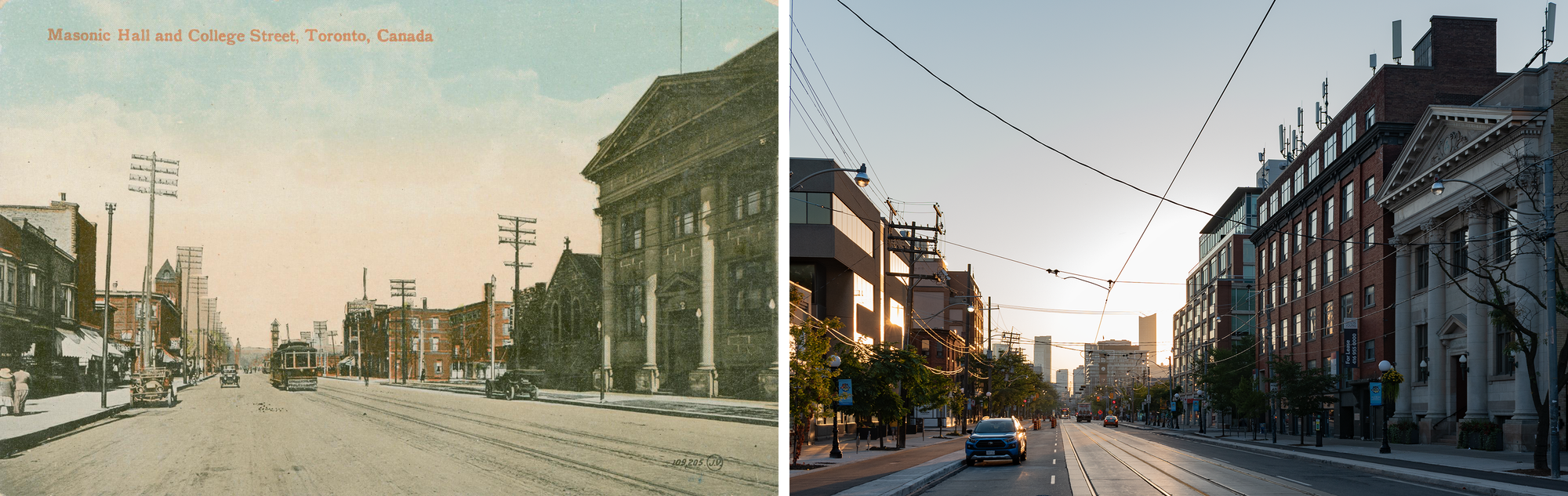

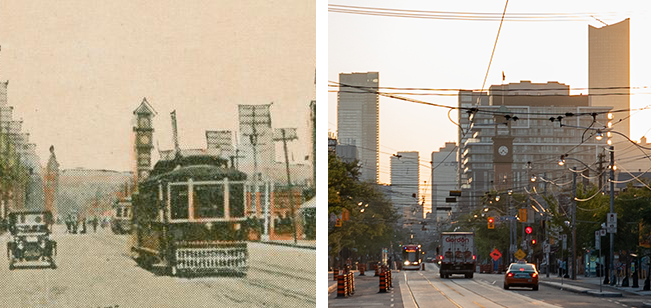

There are a few different Torontos on this block of College Street. Toronto as a boomtown, where a church could be built and demolished in just five years. Toronto as a late bloomer, where a quirk of procurement timing and a relative lack of wealth kept the streetcars running long enough for groups like Streetcars for Toronto to organize to save them in the 1970s. Running through it all is the Toronto of demographic and economic transition, embodied by the former Masonic hall on the right—a neoclassical party venue for WASPy men turned into a hub for Ontario’s Latvian community, now a decorative skin on an especially grandiose liquor store.

So, what’s changed? I like these, because the answer—a lot—befits a city that has grown from fewer than 300,000 residents when this postcard was published in ~1913 to 2.8 million today. The small church on the right, St. Paul’s English Evangelical Lutheran, opened in 1909, but by the end of 1913 it was gone, replaced with the much larger (and more productive) clothing workshops and sheet metal showrooms of the Pedlar People Building. The College Street Masonic Hall is still there, but in the most superficial way possible—after a facadectomy in the 2010s, its neoclassical facade is a thin veneer on an LCBO and office building.

The tower of Bellevue Fire Hall still rises in the distance and, if you look closely, you can still spot the red brick of the building at the corner of College & Markham. Streetcars also still run down College, but they’re TTC (Toronto Transit Commission) rather than TRC (Toronto Railway Company, the private streetcar operator whose franchise the TTC took over). The overhead catenary wires for the streetcars appear to be missing in the postcard, but that’s an artifact of the publishing process—remember, these images were heavy edited.

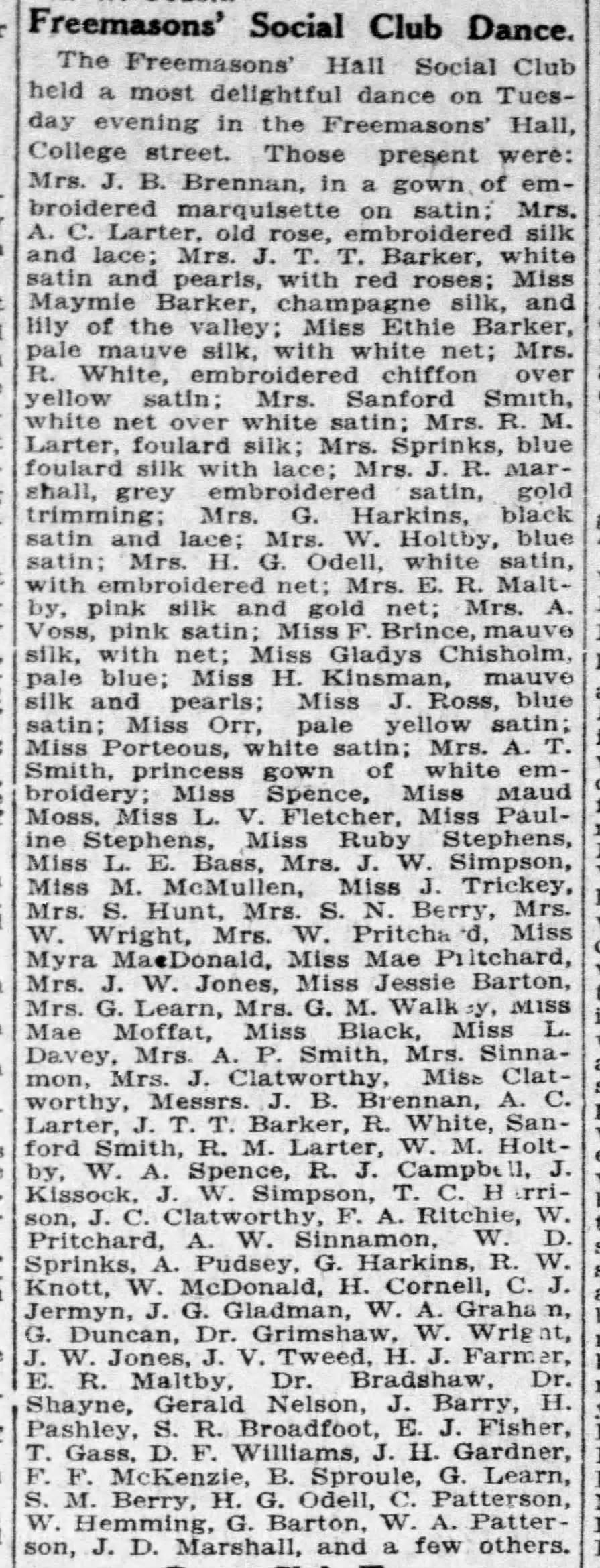

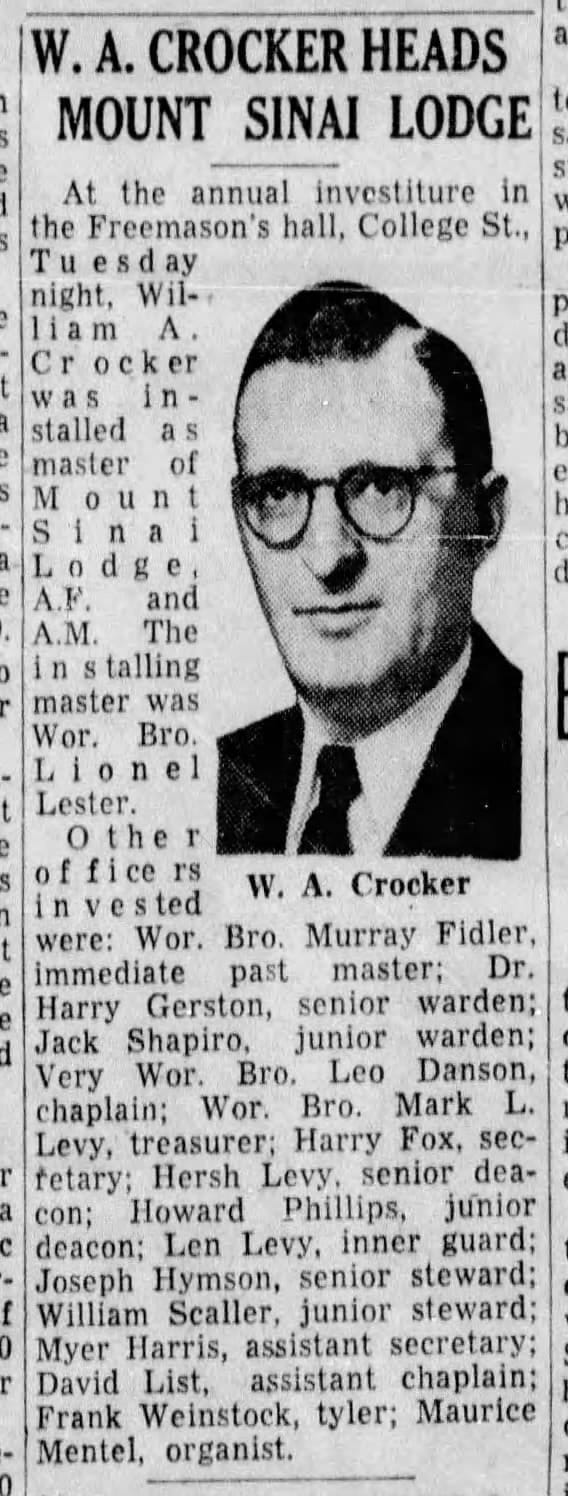

Postcard/photo side-by-side | 1910 article on the masonic hall cornerstone laying | 1911, Freemason dance in the new hall | 1917, the freemasons alter the building | 1920, antiquity smoking concert | 1939, Masonic Lodge assembly | 1953, new head for one of the Masonic lodges | 2023

The College Street Masonic Hall encapsulates one thread of Toronto’s last 115 years. Built in 1910 and designed by Edwards & Saunders, it spent its first few decades as a meeting venue for various Masonic Lodges, Orders, and Rites. Toronto at the time was still quite provincial, very much a city of Commonwealth (nearly 30% of Torontonians had been born in the UK in 1921), and the College Street Masonic Hall was a building-sized expression of that WASPy elite.

By the 1940s and 1950s, though, Toronto was changing, and the immigrant communities making Toronto their home included a burgeoning Latvian community of nearly 10,000. In the 1960s the Latvians turned the former Masonic hall into Latvian House, a cultural and economic hub with a book store, a credit union, and classrooms. Some of those cultural activities moved to North York when the Latvian Canadian Cultural Centre opened in 1979, but Latvian House on College Street continued to house the Toronto Latvian Folk High School into the 2000s, as well as offices of the Latvian Credit Union.

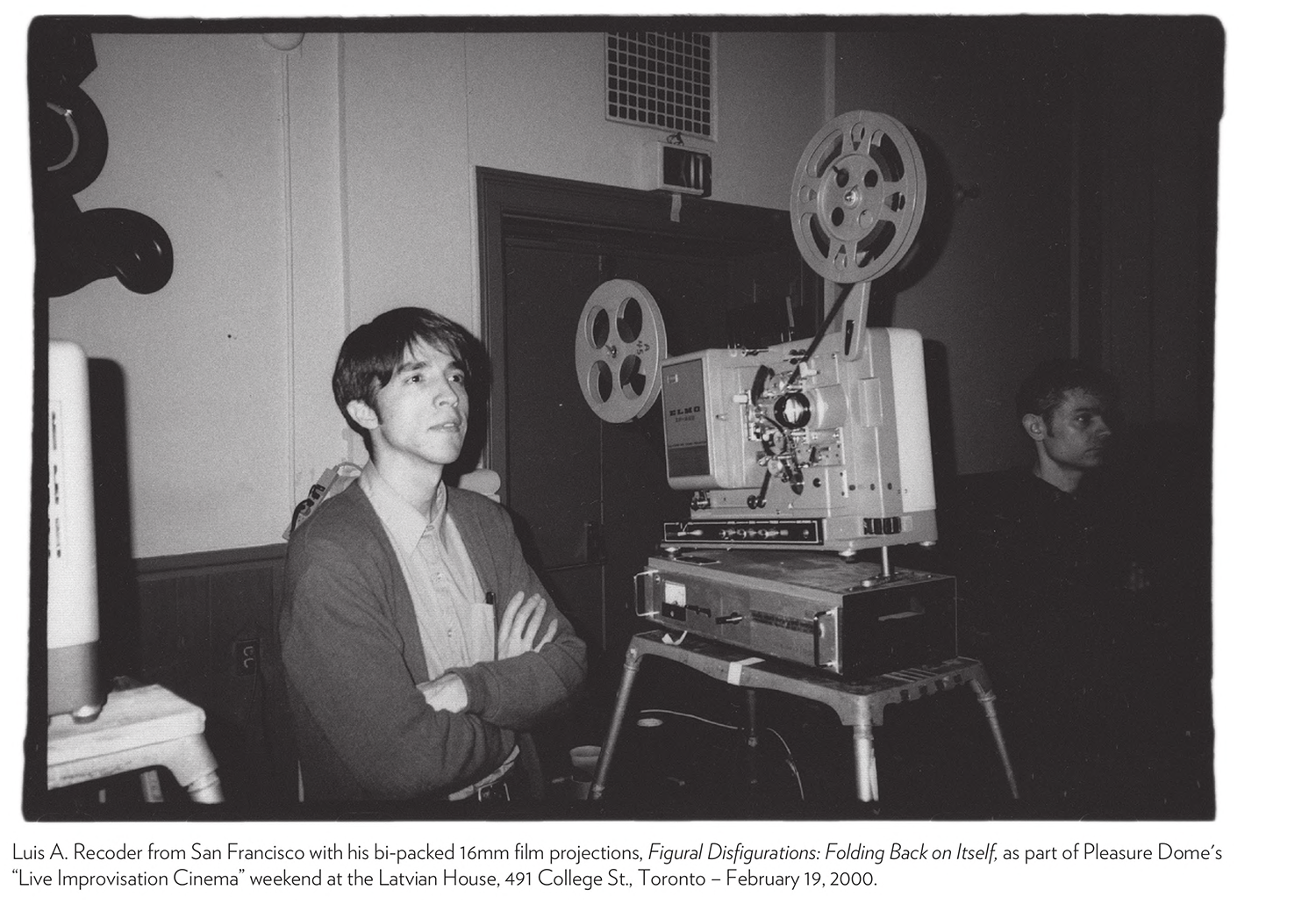

In addition to their own programming, the Latvians regularly rented their space out to others—stuff like anticommunist film screenings by the Edmund Burke Society in the 1960s, punk shows by bands like SNFU in the 1980s, and the Pleasure Dome’s live improv cinema in the 2000s. Unfortunately, they also let some really noxious white supremacists use their venue in the 1990s, including notorious Holocaust denier David Irving—really rancid shit. Don’t do that, otherwise a nobody on the internet will call you an asshole 30 years later.

1965, Independence Celebration at the Latvian House | 1968, Latvian Ski Club meets at Latvian House, The Varsity, the Internet Archive | 1969, in the Edmund Burke Society Newsletter, the Internet Archive | 1974, Latvians Celebrate Brief Liberty | 1978, new Latvian centre | 1982, Toronto Public Library | 2000, John Porter’s CineScenes, the Internet Archive | 2008, petition to wind up Latvian House Limited | 2013 rendering of the new development, eventually scaled down

With the Latvian community shifting towards outlying neighborhoods and the suburbs, in 2008 the Latvian House moved to sell the building and dissolve itself. Combined with a surface parking lot next door, this was a compelling development site, and by 2013 there were plans for a glassy midrise that reused the neoclassical facade. The developer’s plans shrunk, but in 2016 they demolished everything but the neoclassical facade and built a new three-story mixed-use building behind it. With the old facade decorating only half of the new development, it looks like two buildings, but in reality it’s a single building with a split face. Designed by Turner Fleischer Architects, it opened in 2018 with a ground floor LCBO and two floors of offices above.

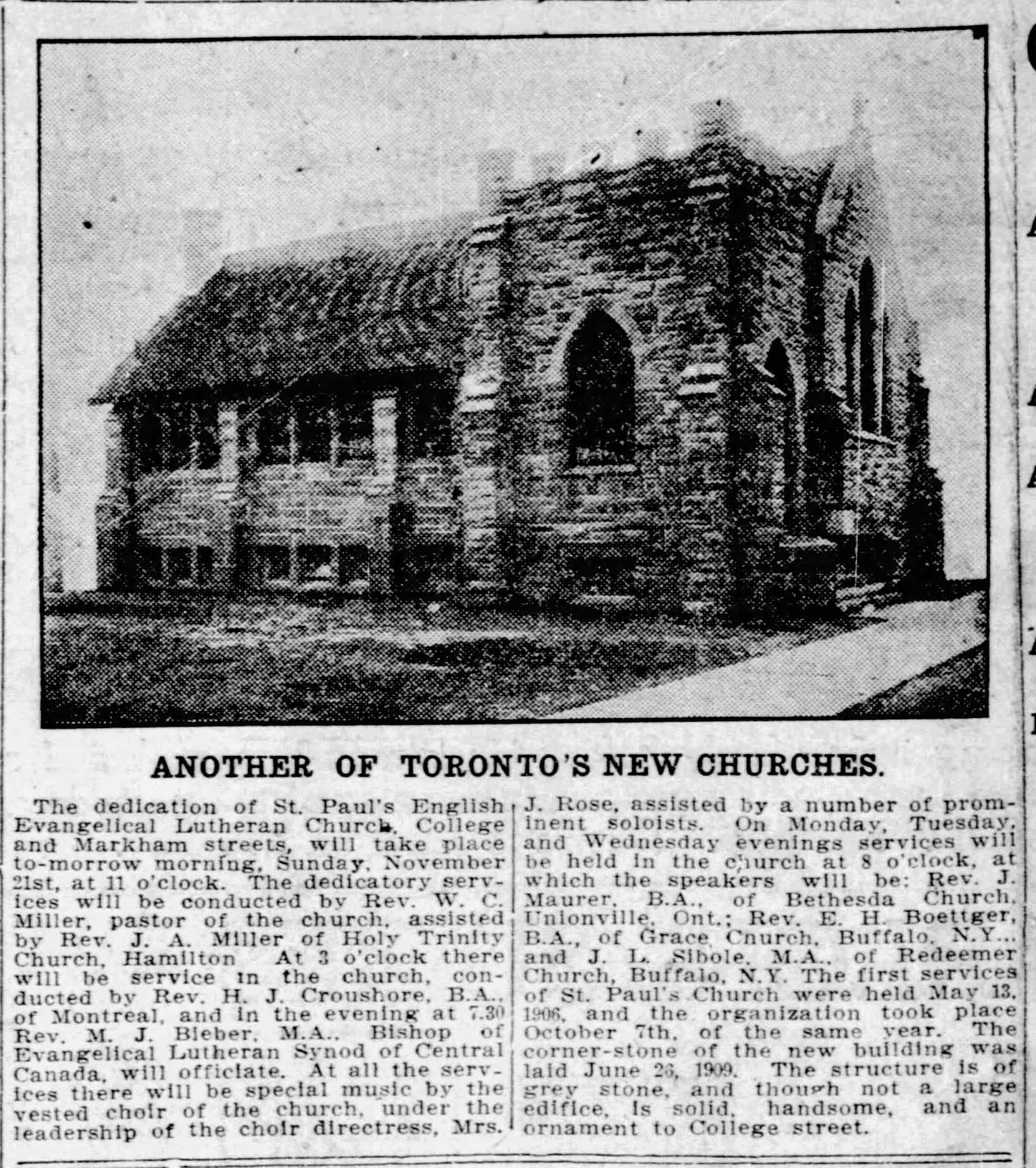

The short-lived church next door—St. Paul’s English Evangelical Lutheran Church—opened in 1909. The Toronto Star described the church as “not a large edifice, is solid, handsome, and an ornament to College Street”. The congregation either quickly outgrew that building, or received an offer they couldn’t refuse—by spring 1913 the building was sold and available for removal or demolition. St. Paul’s congregation built themselves a new church building (larger, but still pretty small) less than two kilometers away on Glen Morris Street—that church is still there, now home to the Luella Massey Studio Theater of the University of Toronto St. George Campus.

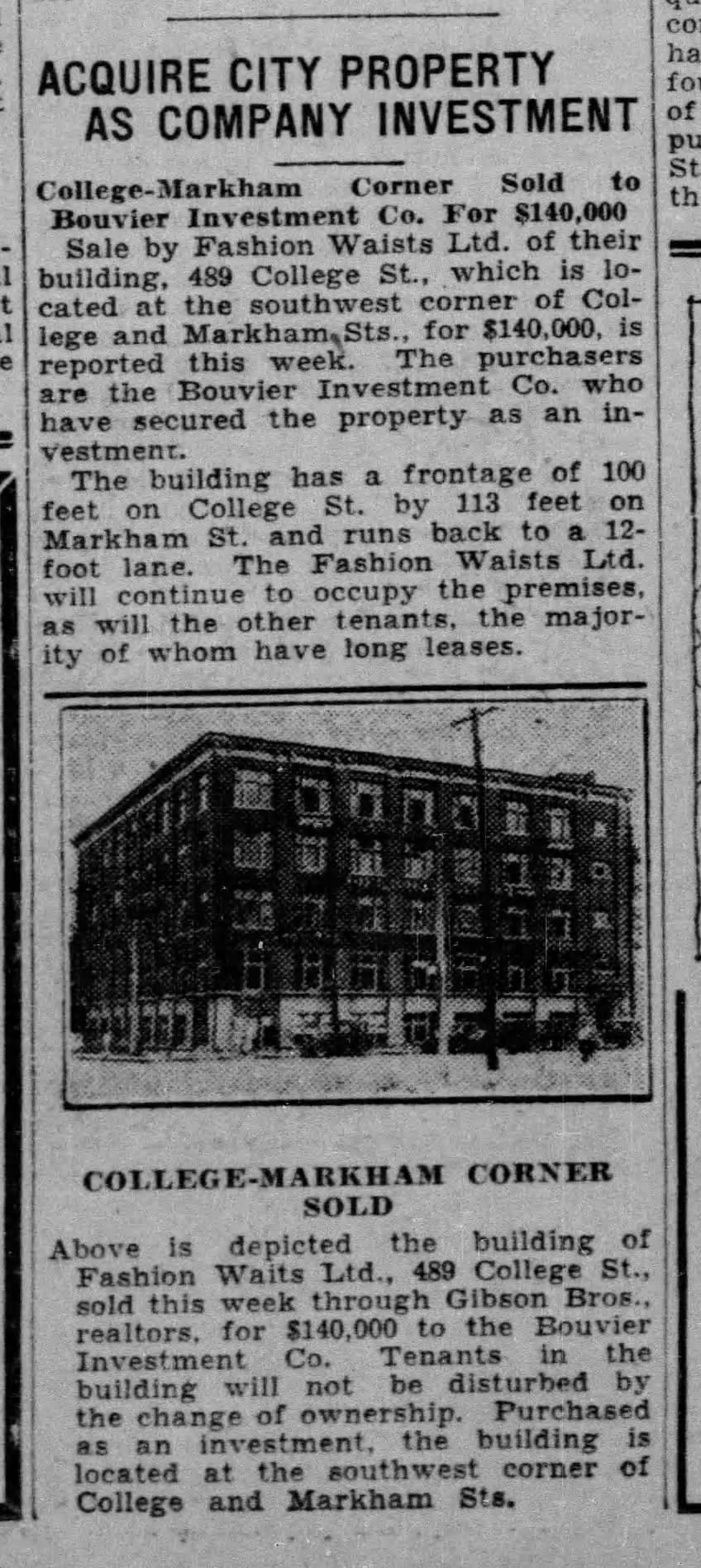

1909, new church | 1911, church five year anniversary | 1913, church for sale | 1913, cornerstone laying for the replacement church | 1913, Pedlar People move into the new building | 1929, building sold | undated photo, Toronto Star Archives, Digital Archive Ontario | 1934, going out of business sale

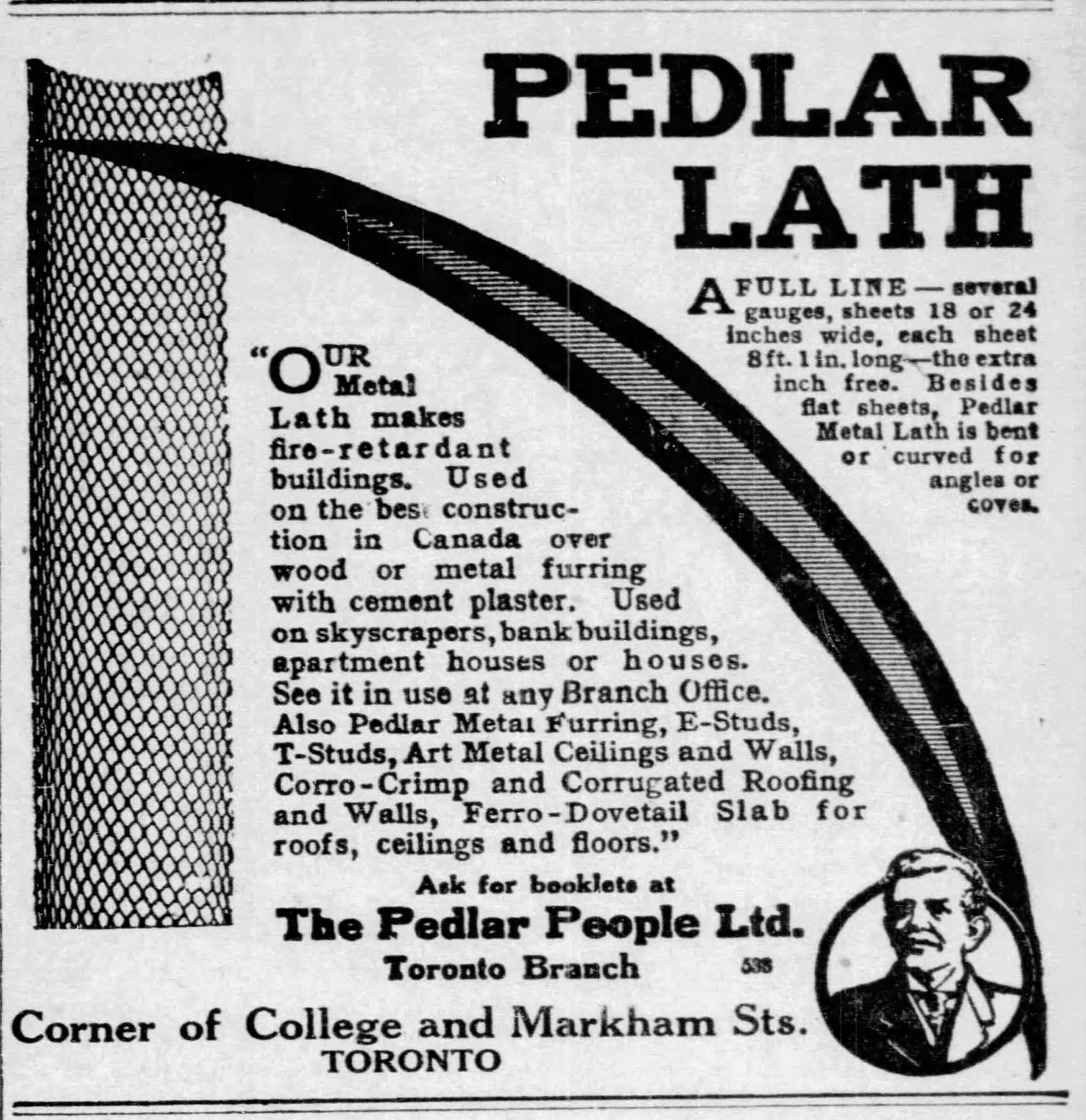

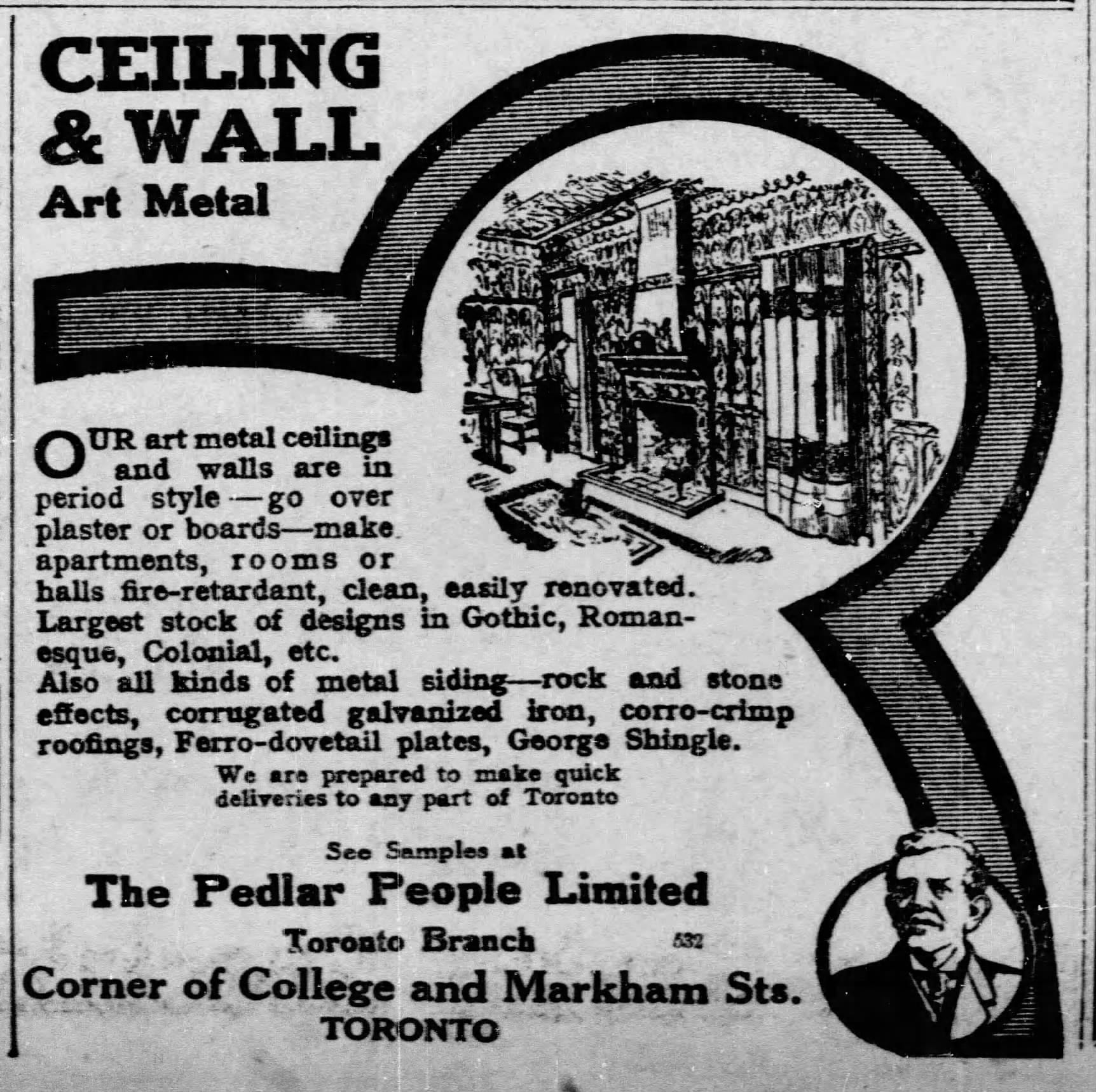

The church’s replacement, a burly six-story brick industrial building, was designed by Frank R. Cowan and built between 1913 and 1914. Mostly home to clothing workshops, it opened with a showroom and workspace for the Pedlar People Company, a decorative sheet metal manufacturer based in Oshawa. Upstairs, tenants like Fashion Waists Ltd., Louis Korn & Son, and Cook Brothers & Allen made lingerie, men’s suits, and sportswear into the 1980s. No clue when they added a floor on top. Its style and shape also influenced the form of the modern condo building across the street, the Ideal Lofts, designed by architectsAlliance and opened in 2002.

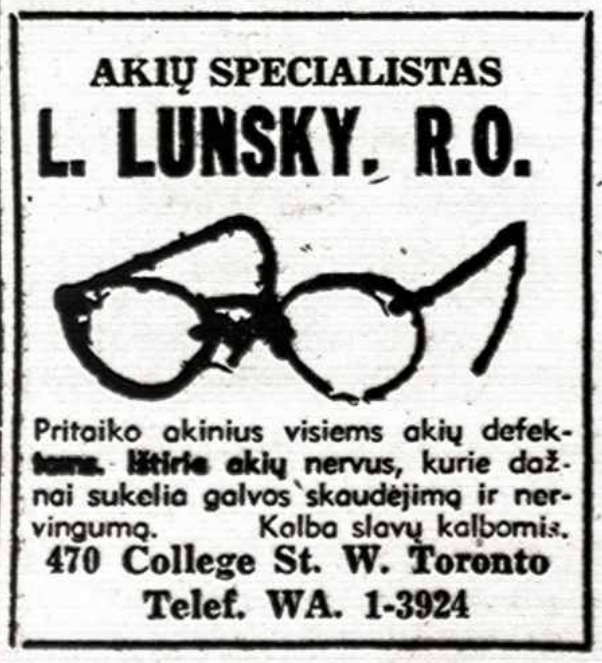

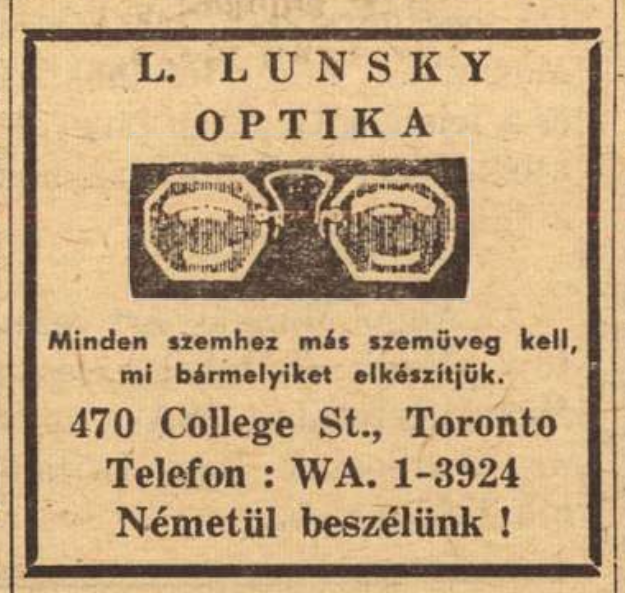

Postcard/photo side-by-side focused on 470 College Street | 1937, Lun(d)sky Optometry Ad | 1954, Lithuanian language ad | 1959, Hungarian language ad | Lunsky Optometry Facebook post looking for a receptionist with Portuguese skills | undated photo | 2023

Across the street, 470 College Street has been there since at least 1890, which feels pretty ancient for this part of Toronto. For nearly 100 of those years it has been home to Lunsky Optometry, founded in 1933. You can trace neighborhood change in Lunsky's public communications, which transitioned over the decades from ads in Hungarian and Lithuanian to job ads specifying Portuguese language skills.

Rolling through the center of it all is a Toronto streetcar, which was saved by sustained public pressure after the TTC announced plans in 1971 to end all streetcar service by 1980.

…but most North American cities had already begun to rip up their streetcar systems in the 1940s and 1950s. Chicago’s last streetcar ran in 1958, Montreal’s in 1959, Los Angeles’ in 1963—how did Toronto’s streetcars survive long enough for citizen opposition for Toronto to matter?

As far as I can tell, it’s a reflection of a quirky sequencing, effective management, and Toronto’s position as a relatively late bloomer, rather than any unique Torontonian affinity for streetcars in comparison to its peer cities. Toronto at midcentury wasn’t especially wealthy or fashionable, and it wasn’t even the most important city in Canada. In this case, though, that slightly provincial position turned out to be an asset, since the fashion at the time—ditching streetcars for buses—kinda sucked.

The timing of Toronto's streetcar procurement process also kept the streetcars running long enough for opposition to materialize. The TTC had invested in a new streetcar series somewhat late, in 1938, and the need to amortize that asset—a new streetcar had to run for 20 years before paid for itself—prevented the TTC from jumping onto the bus conversion craze (Chicago, for example, was already converting streetcar lines to bus service by the late 1940s). That procurement path dependency meant that Toronto spent the 1950s growing their streetcar fleet with used streetcars from US cities who had removed theirs, rather than spending that decade converting streetcar lines to bus service. None of that would have mattered if the streetcars were poorly run, but the midcentury TTC was also effectively managed, with streetcars moving more people, more efficiently, and more cheaply than buses.

Procurement sequencing, a humble financial position, and effective management kept streetcars clacking down College Street into the 1960s. Then, with Toronto blossoming into a more ambitious city, its leadership looked around and basically said “well, the biggest cities ditched their streetcars, and we aspire to be a big city, so we should too”.

Thankfully, the TTC embarked on that process at least 20 years later than their peers—a better informed and better equipped civil society organized in opposition, and the Streetcars for Toronto Committee formed in 1972 to fight the plan to dismantle the streetcar system. Within a year, the public preference for streetcars, their capacity advantages in comparison to buses, and activist pressure paid off and the TTC Board voted to retain the streetcar system.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Toronto: Capital of the Latvian exile community by Viesturs Zariņš

- Among the fascist assholes the Latvian House hosted: White Aryan Resistance, David Irving, Heritage Front, etc.

- Canadian punks SNFU were interviewed about a show they played here in 1986 in fanzine Confuzed in 1986.

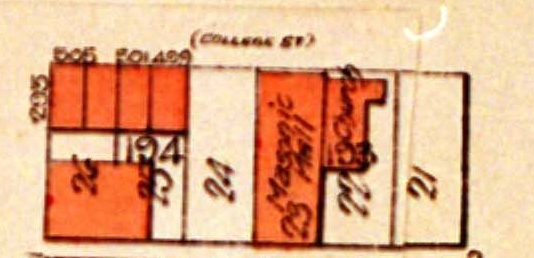

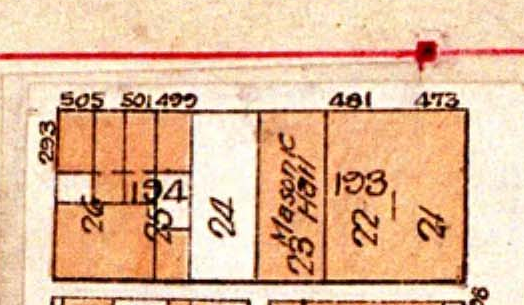

In the 1910 and 1923 fire insurance maps.

Some ads from the sheet metal and clothing companies that operated out of the brick building at 489 College Street.

Pedlar ads from 1913, 1913, 1914, and 1916 | 1934, two 1Cook Brothers & Allen going out of business sale ad | 1936, Dunn's ad

Some of the help wanted ads for the sheet metal company and clothing workshops in 489 College Street over the years.

1915, tailors wanted | 1916, tinsmith help wanted | 1917, pant finishers wanted | 1918, Fashion Waists Ltd. help wanted | 1919, Cooke Bros. and Allen looking for a young boy | 1931, Fashion Waists wants a zig zag operator | 1941, Louis Korn wants needle help to make bras | 1946, Ritchie Faber wants bushellers | 1985, sportswear producer searches for checkers

Thought this correction was a little funny—St. Paul's church was not made out of stone.

Member discussion: