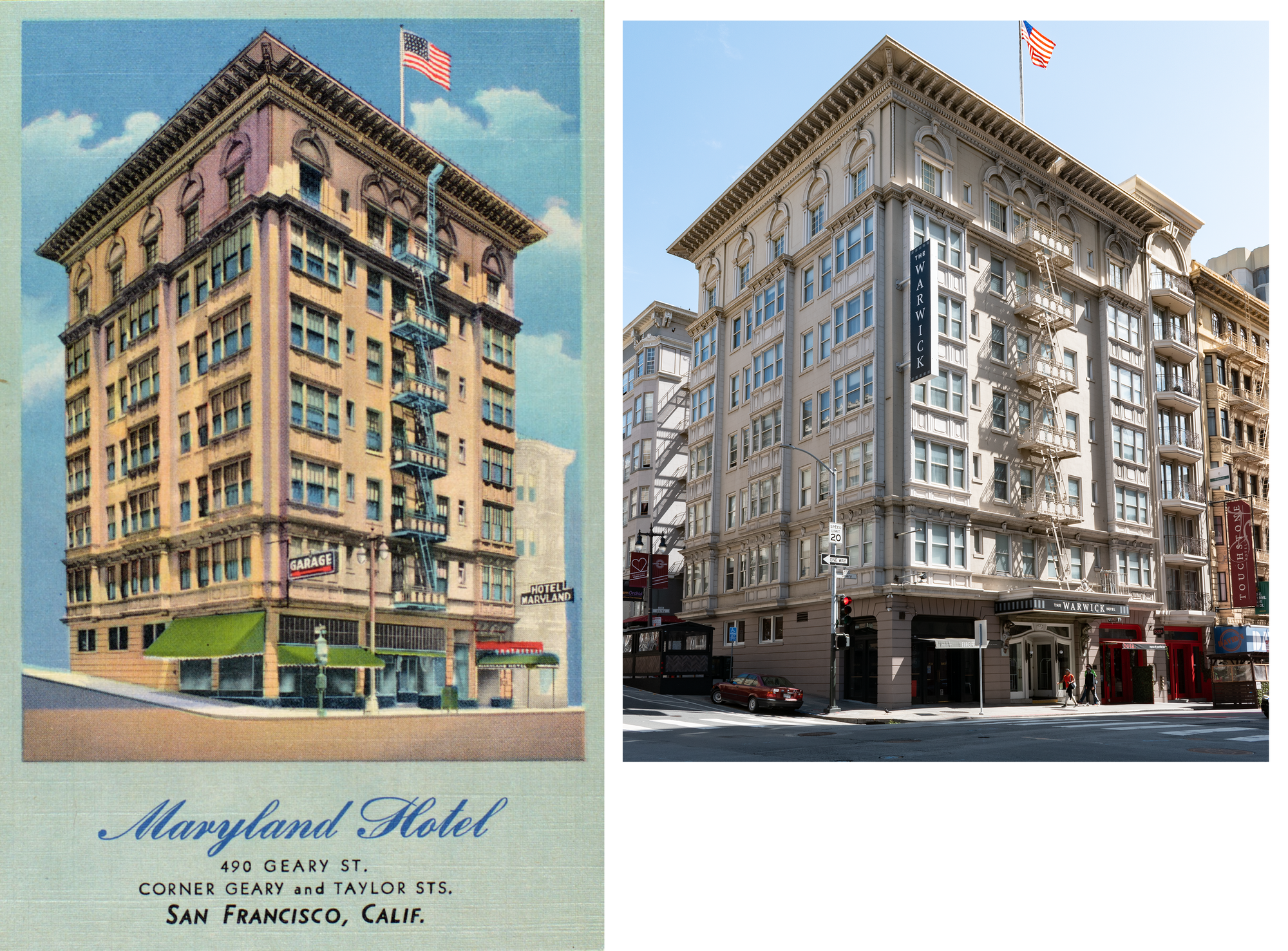

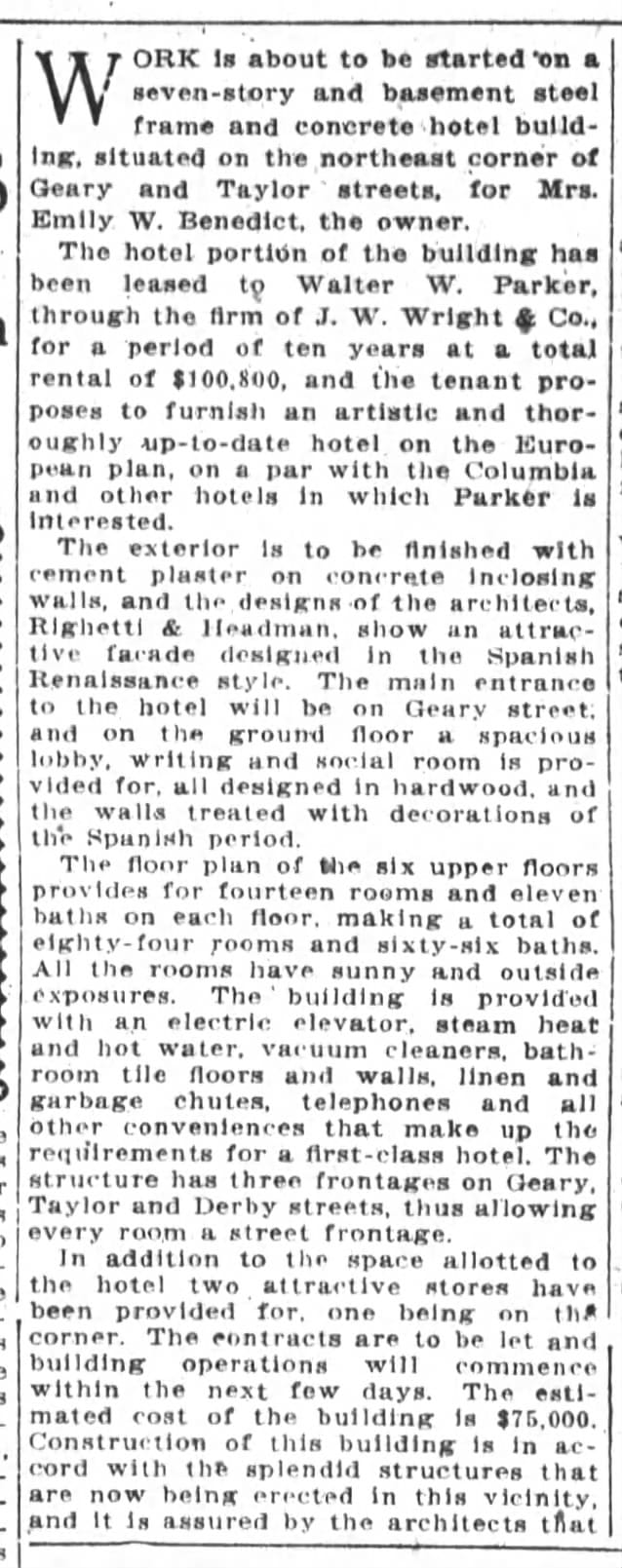

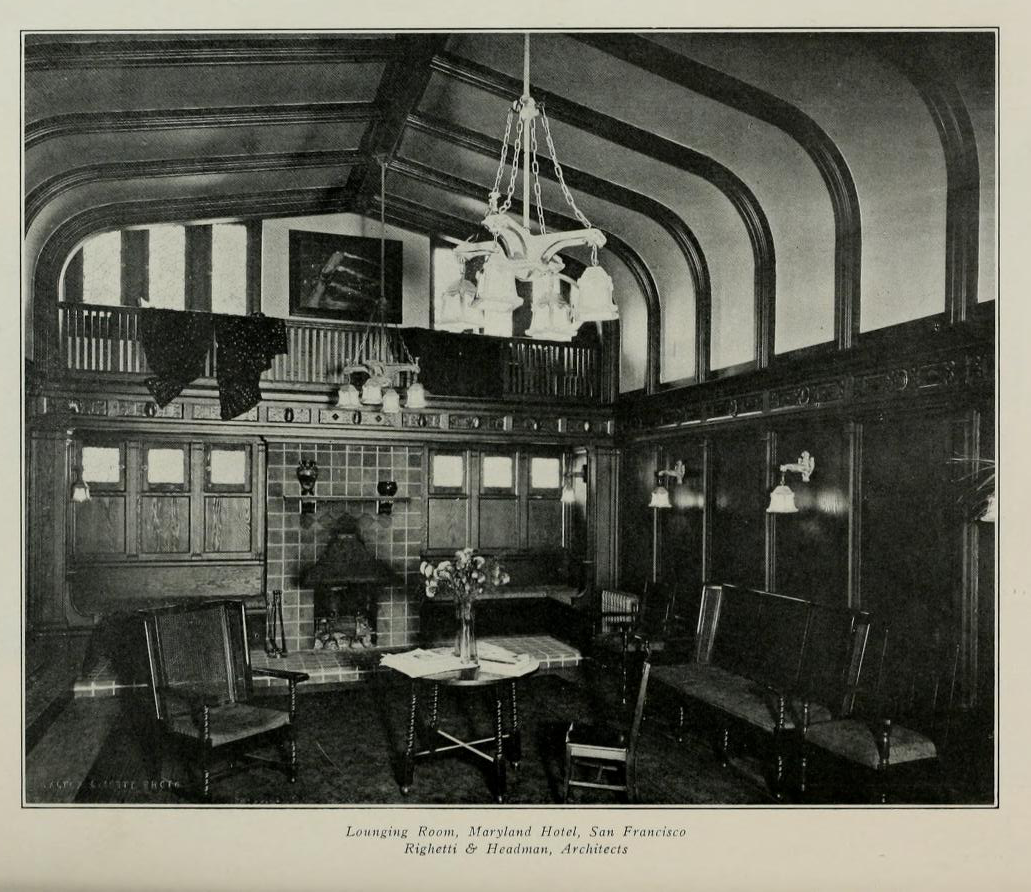

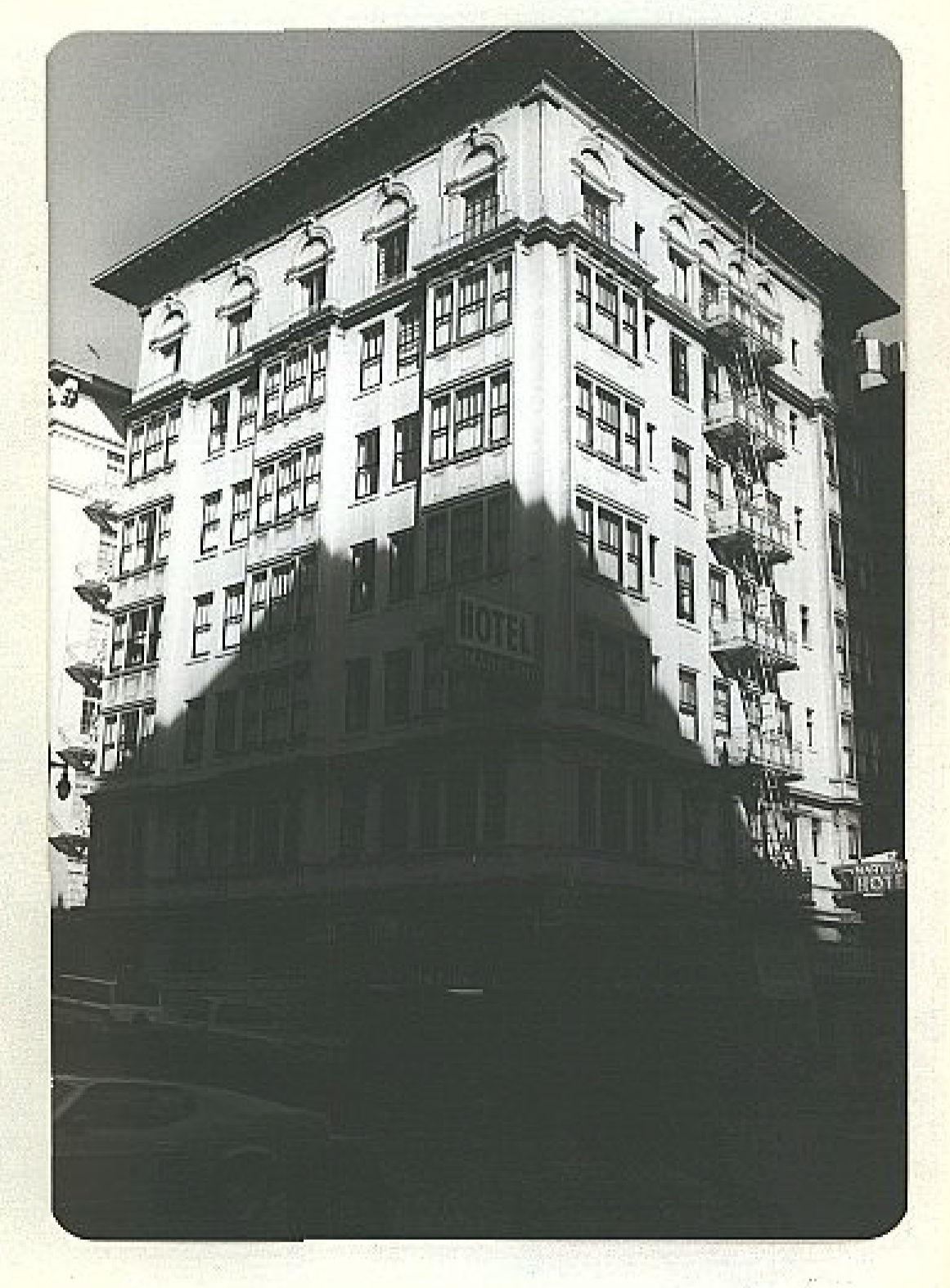

A tidy Beaux Arts hotel designed by Righetti & Headman on the edge of the Tenderloin, the Maryland Hotel was built in 1912 and followed an extremely typical trajectory for a San Francisco residential hotel. Built as a middle class residential hotel, owner neglect, regulatory pressure, and social stigma pushed it further and further downmarket as an SRO over the decades until—part of the wave of 1980s SRO conversions in which the city lost 43% of its affordable residential hotels—the tenants were kicked out and the building (legally in this case, unlike many others) converted into a tourist hotel.

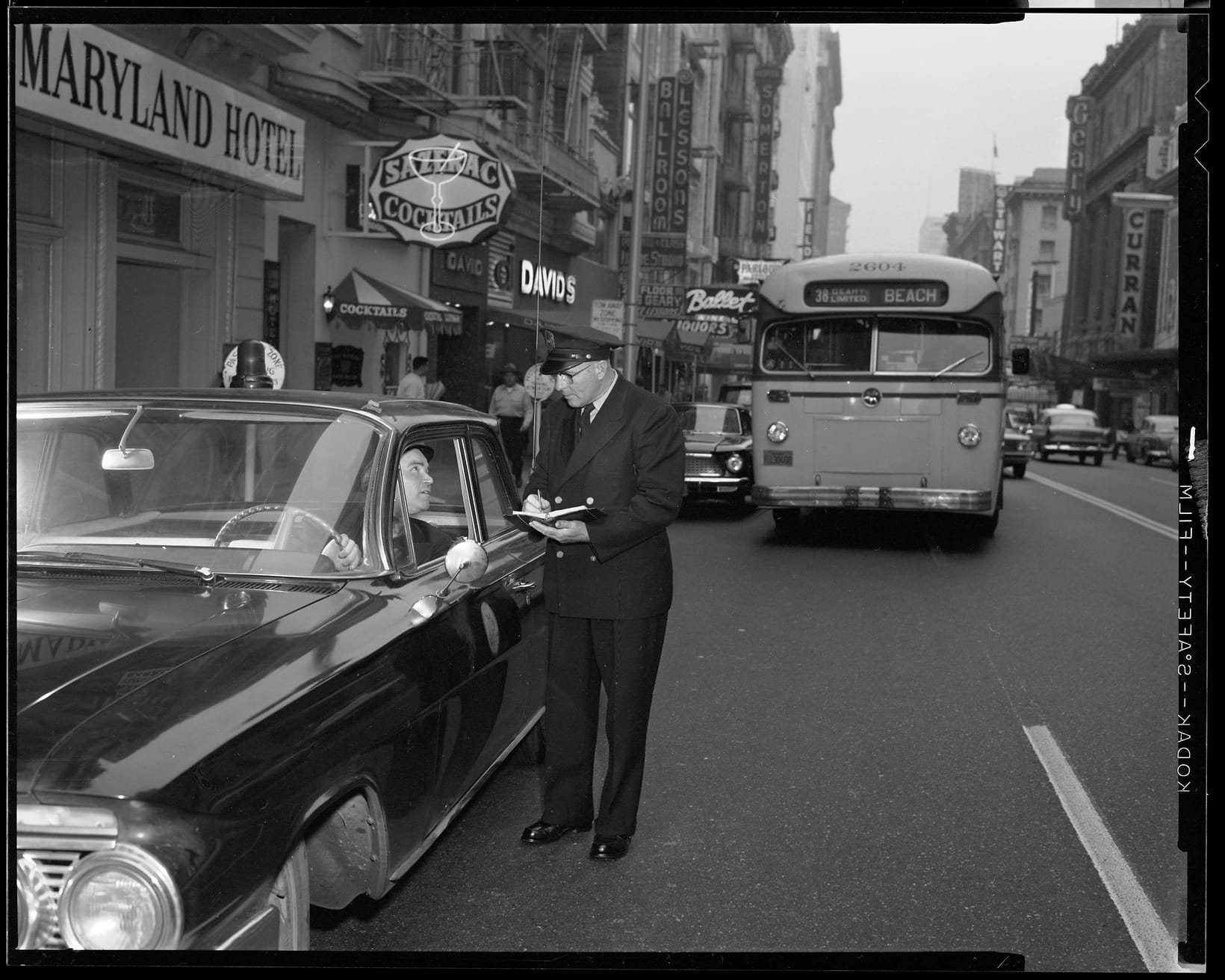

So, what's changed? Some rearranging of retail space and entryways on the first floor, with a new canopy for a reconfigured entrance to the hotel. There was a sign on the corner by 1923, so I imagine it was airbrushed out here. The "GARAGE" sign is gone, but you can still spot its vestigial metal supports. The biggest change is next door—the narrow, short building on the right was demolished and rebuilt into a hotel addition in the mid-1980s as part of the building's conversion into a tourist hotel.

1911 rendering and article about work starting on the building | 1913 photos exterior and interior, The Architect & Engineer of California and the Pacific Coast, the Internet Archive | 1923, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library | ca. 1960 photo, OpenSFHistory / wnp14.2047 | 1962, Marshall Moxom, SFMTA Photo Archive

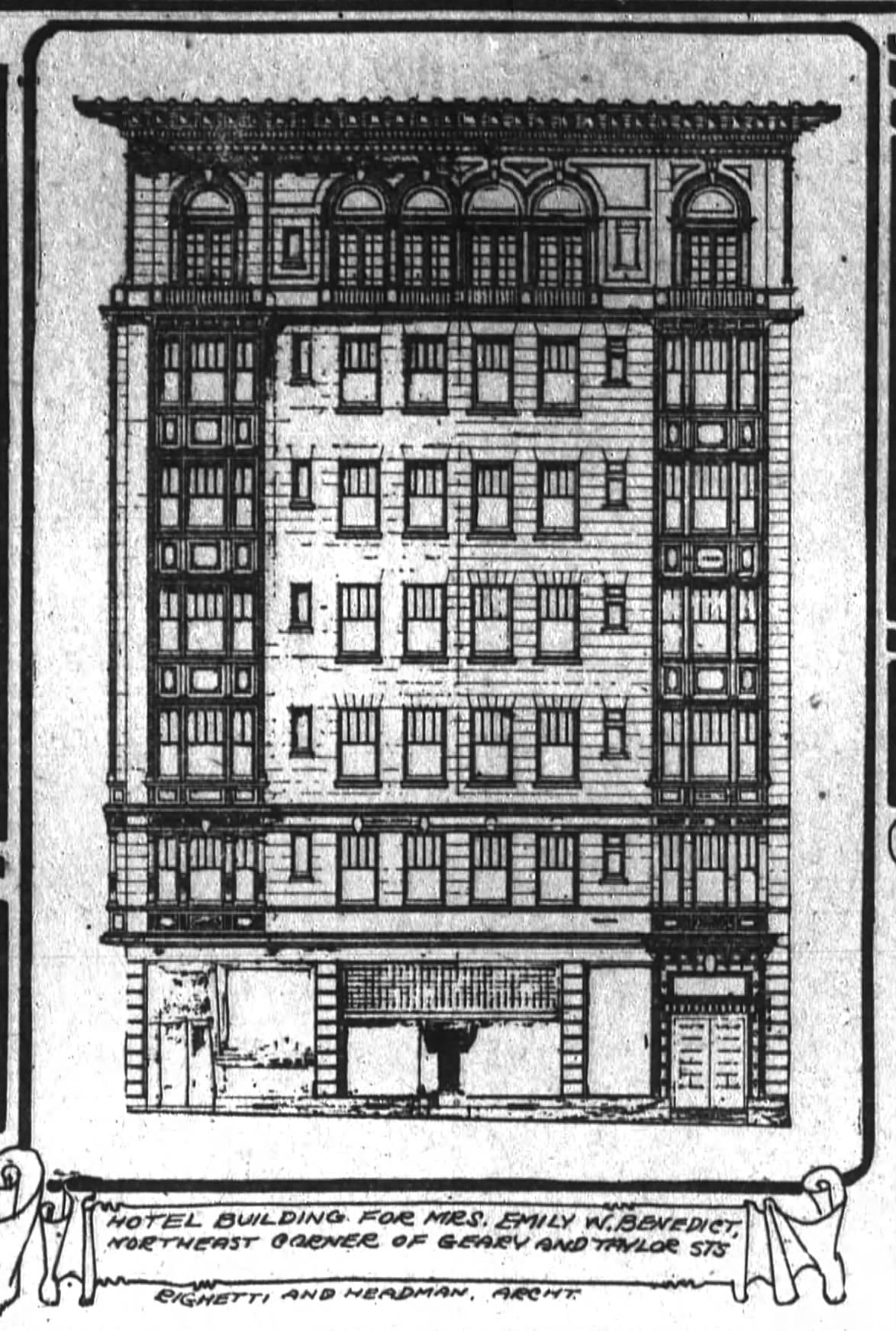

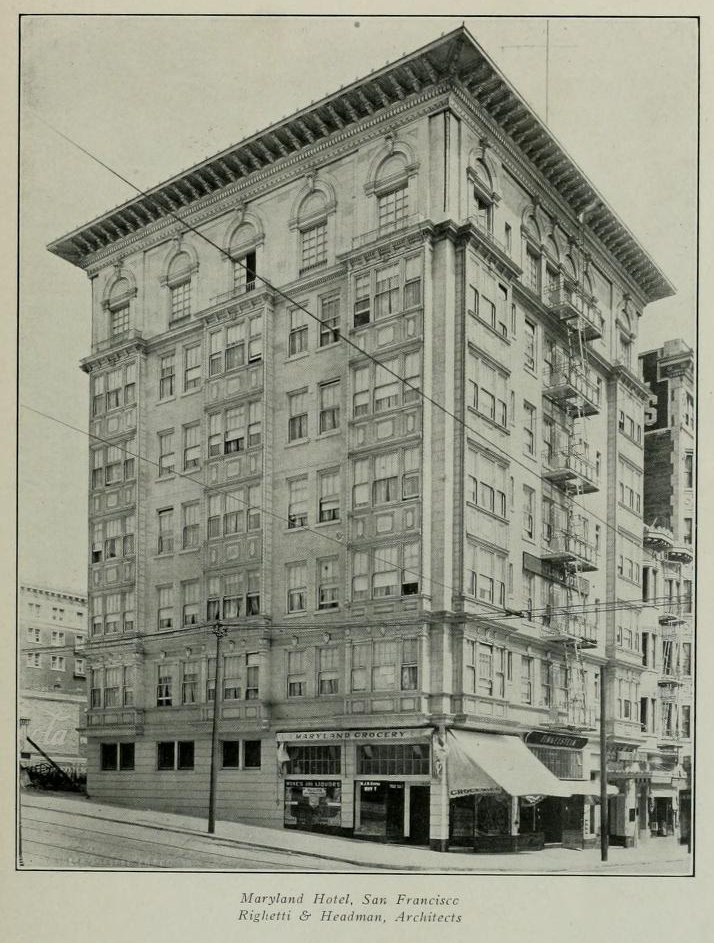

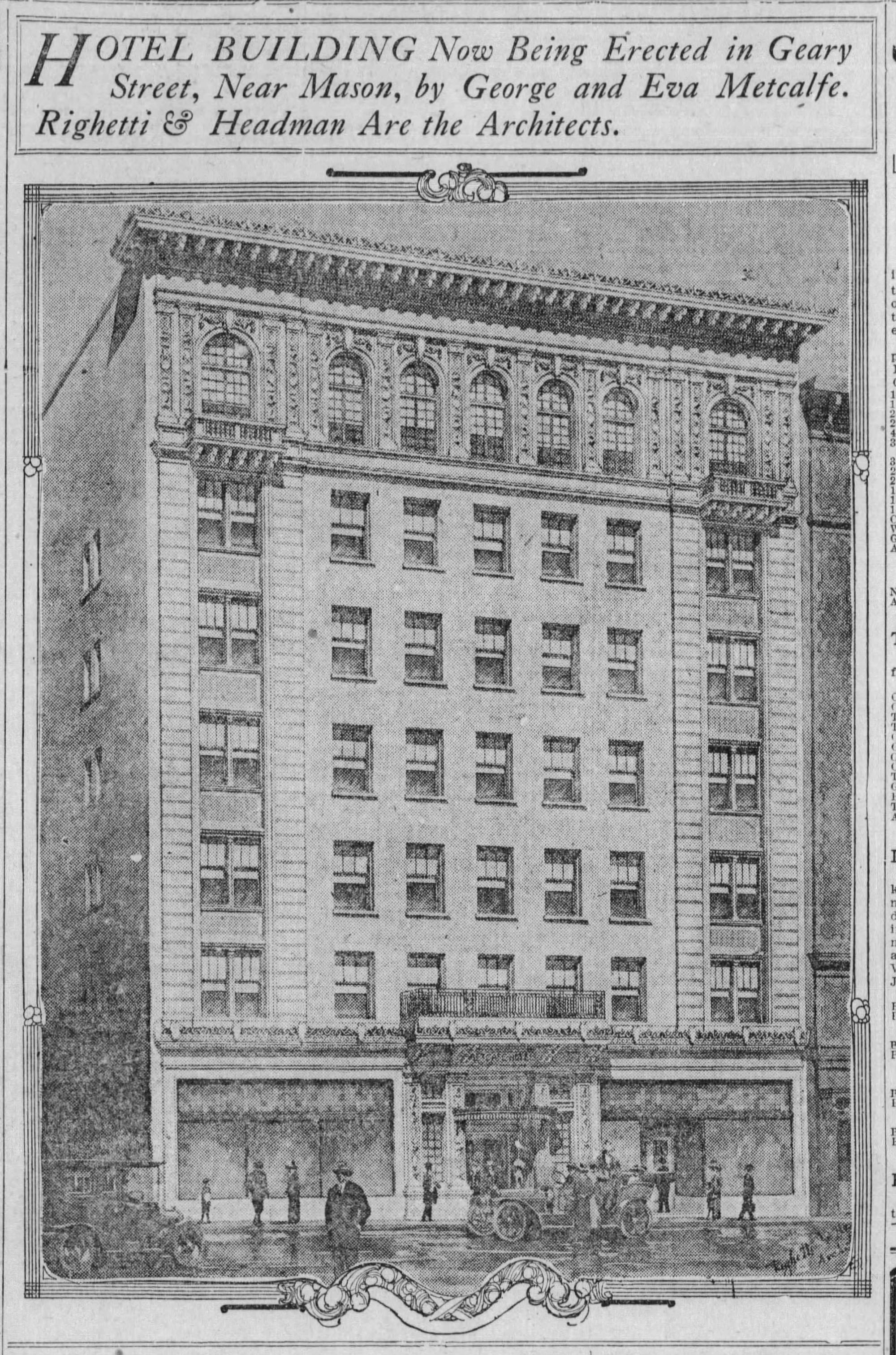

Emily W. Benedict, the widow of a chemicals heir, owned this lot on the corner of Taylor and Geary streets, hiring architects Righetti & Headman to design a seven-story hotel in 1911. Emily's late husband, the source of her wealth, was named Egbert Judson Benedict—you could say that Egg Benedict built this hotel.

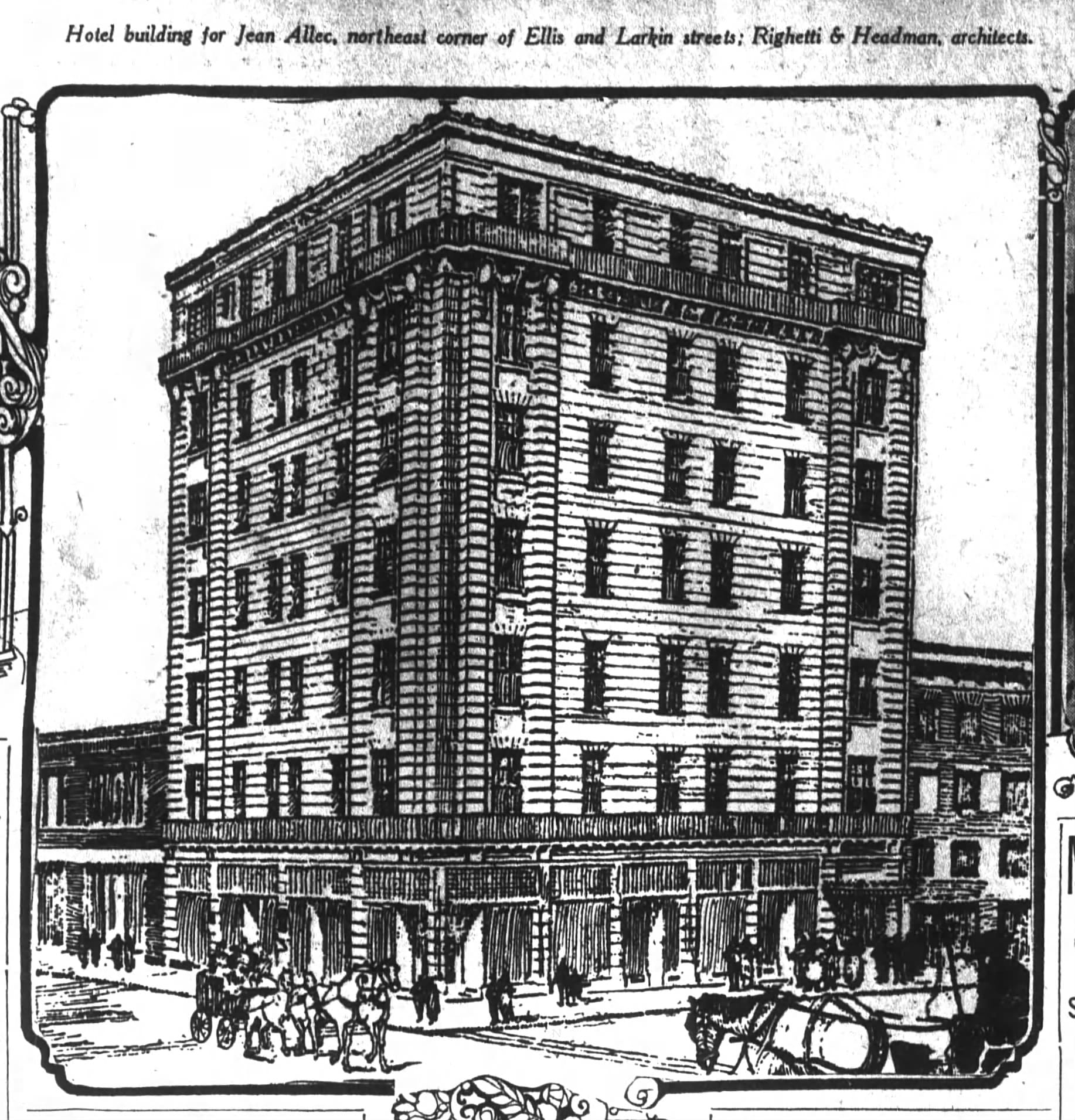

Righetti & Headman took advantage of the post-earthquake building boom to design a crop of apartments and residential hotels in this area during their relatively short partnership, which lasted from 1909 until 1904. All similarly classically inspired, the most best thing about their firm might’ve been Headman’s full name: August Goonie Headman.

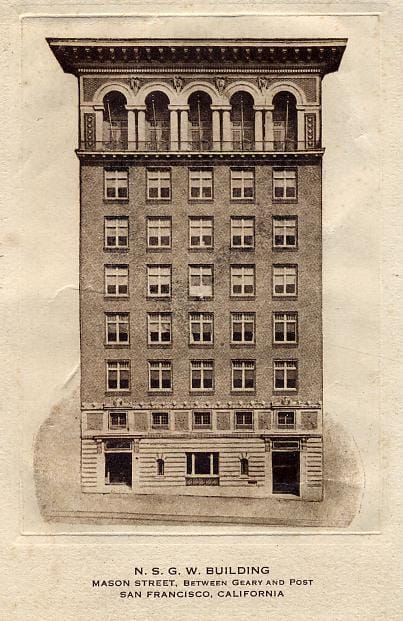

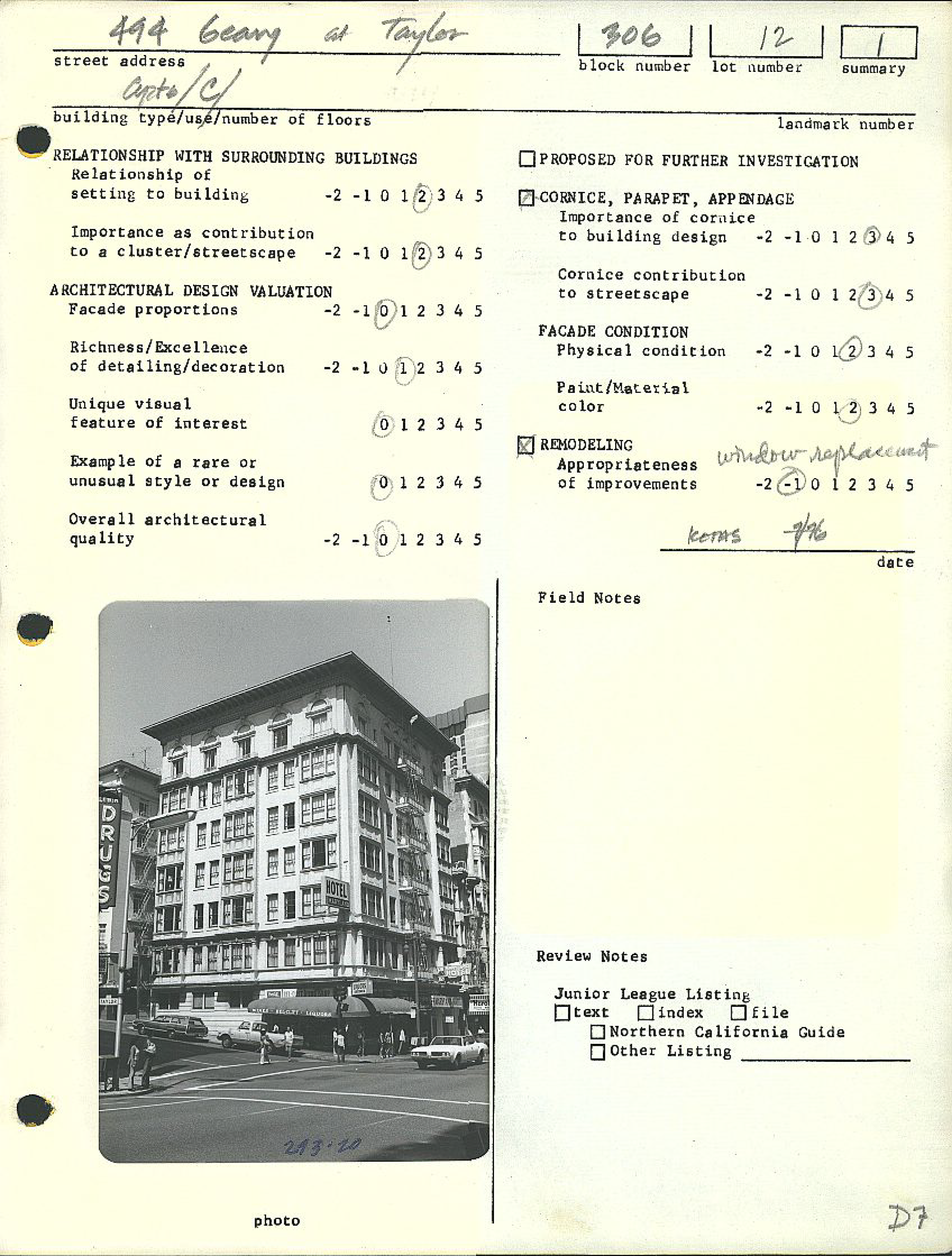

The Maryland is Beaux Arts with Spanish Renaissance Revival style detail, but there are handful of other Righetti & Headman-designed buildings within a couple-block radius of the hotel, including the Native Sons of the Golden West Building, the Union Square Plaza Hotel (built as the Metcalf Hotel), and the Hotel Essex.

Maryland Hotel, 1976 Survey, DCP | Native Sons of the Golden West Building, Wikimedia Commons | 1912, Metcalf Hotel | Metcalf Hotel, 2025 Google Streetview | 1913, Hotel Essex | 2019, Hotel Essex Google Streetview

The Maryland contained 60 to 80 units over its first 70 years, part of a San Francisco SRO stock that was once 90,000 deep. SROs aren’t perfect, but they’re a cheap, flexible, and independent form of housing that doesn’t require a credit score or a security deposit—they can be a lifesaver for people with housing insecurity.

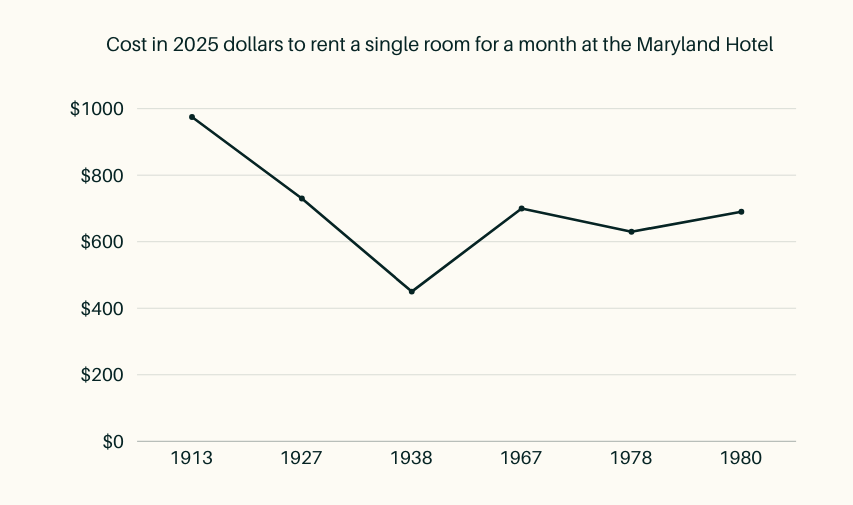

Even as the building deteriorated, SRO units disappeared, the economy boomed and busted, and San Francisco gentrified, rents at the Maryland stayed pretty steady in the $600-$700 a month range into the early 1980s.

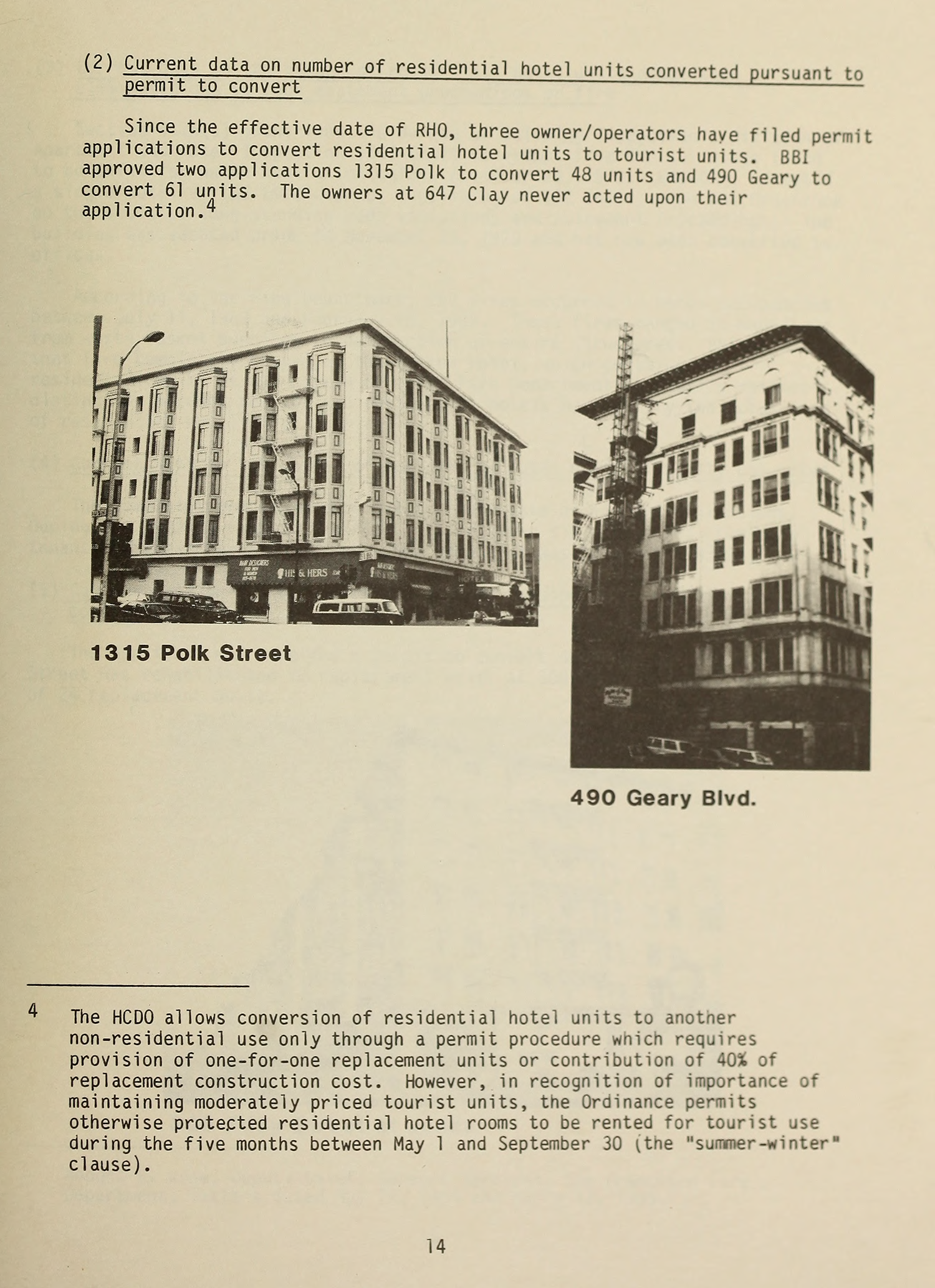

The transformation of the Maryland into the Regis Hotel in the mid-1980s was part of a wave of SRO-to-tourist conversions in San Francisco—between 1975 and 1988, the city lost more than 40% of its low‐cost residential hotels. With the Bay Area building virtually zero new housing (no change there), displaced SRO tenants were forced into even more dilapidated SROs (the ones in such shitty shape they weren't candidates for tourist hotel conversion) or onto the street. To stem the bleeding, San Francisco passed a moratorium on SRO conversions and demolitions in 1979, formalized with a permanent Residential Hotel Unit Conversion and Demolition Ordinance (HCO) in 1981 that tightly regulated whether and how an SRO could be demolished or converted into another use.

For a couple reasons, the city created the HCO with loopholes. One, the ordinance needed to be limited enough that the California Supreme Court wouldn't consider it an unconstitutional government taking of private property. Two, much of San Francisco's political elite personally supported the conversion of SROs, both as a way to "clean up" the Tenderloin and as a way to enrich themselves (then-mayor Dianne Feinstein was literally converting an SRO she owned into a tourist hotel as the HCO was legislated!). That said, the ordinance, coupled with tenacious activist attention that continues to this day, has mostly stemmed the bleeding—San Francisco has a stable-ish stock of roughly 19,000 SRO units today.

1976 Field Survey, DCP | HCDO Status Report, 1985, Internet Archive | 1985 article and rendering of the renovation and expansion | 1984 conversion protest, Internet Archive | 1985 demolition application for the building next door, Internet Archive

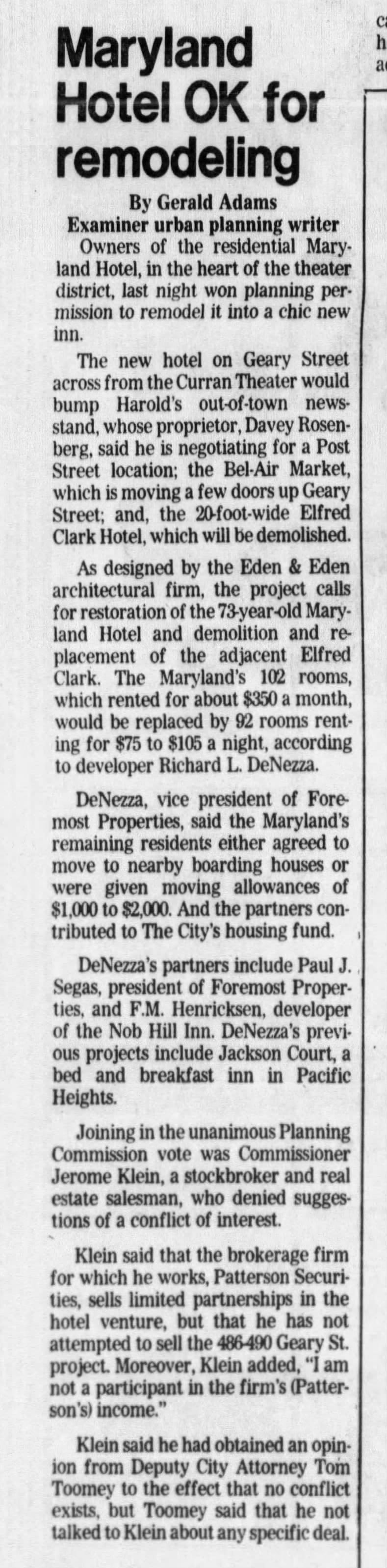

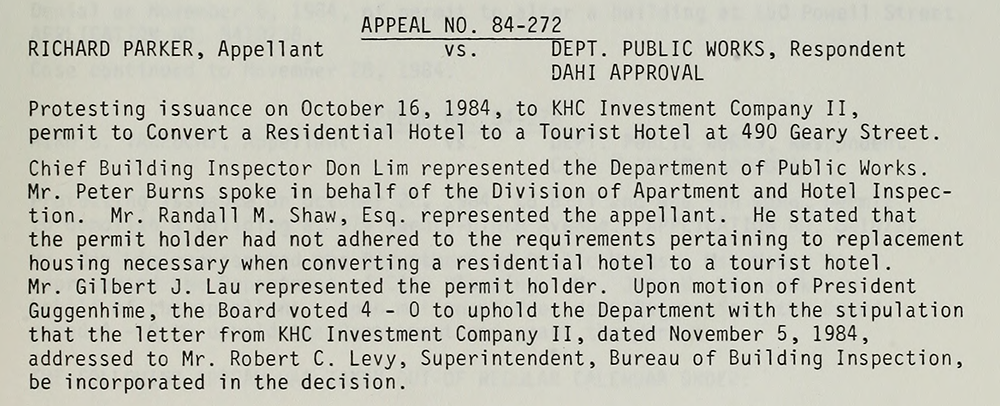

So in 1984, the Maryland sold and the new owners applied to convert it into a tourist hotel. To win approval, the HCO required they pay the city's Hotel Preservation Fund 40% of the construction cost of replacement units. Even after the city approved the conversion, the Maryland's tenants fought on, appealing to the Board of Permit Appeals. They lost, but in addition to the required payment to the Hotel Preservation Fund, tenants were either assisted with moves into other SROs or provided with moving allowances of $1k-$2k.

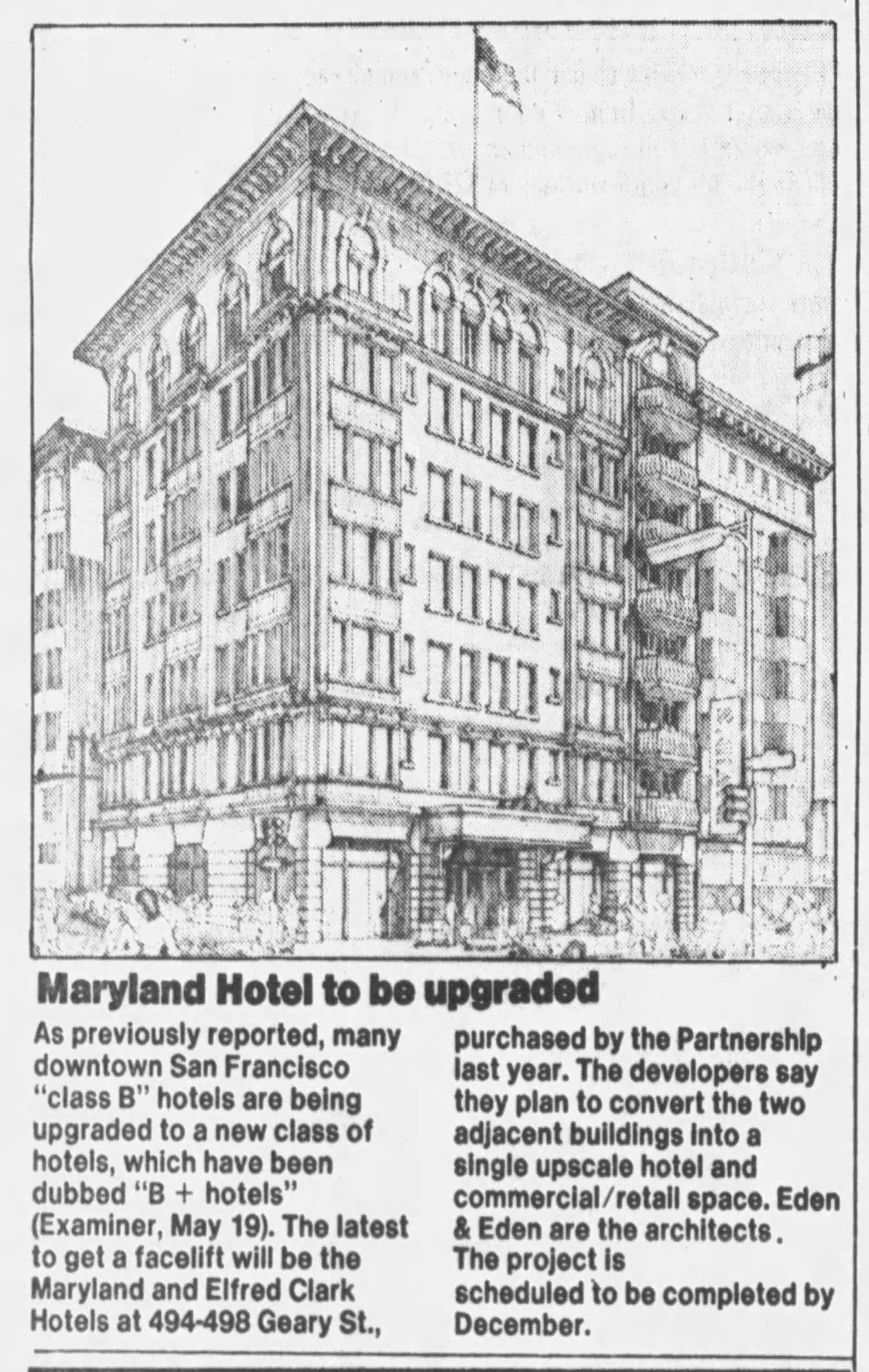

The thin, short building to the right—the Hotel LeFord—was torn down in 1985 and rebuilt as a hotel addition during the conversion of the Maryland into a tourist hotel. The LeFord, also known as the Elfred Clark Hotel, was only 20 feet wide—I'd love to understand how the economics of that penciled out. The converted and expanded hotel, designed by Eden & Eden architects, opened as the Regis in 1986.

A mid-2010s renovation, designed by UXUS, vaulted the once-shabby SRO and "B+ Tourist Hotel" (a “B+ Hotel” was the real term used at the time, I’m not throwing shade at the Warwick) up another level, and today the Warwick is a boutique hotel.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States by Paul Groth

- "The Recent Work of Messrs. Righetti & Headman, Architects" in The Architect & Engineer of California and the Pacific Coast, 1913

- "Hotel Boycott–TAC Takes it to the Streets" in the Tenant Times, 1981

- Single Room Occupancy Hotels in San Francisco: A Health Impact Assessment, 2016

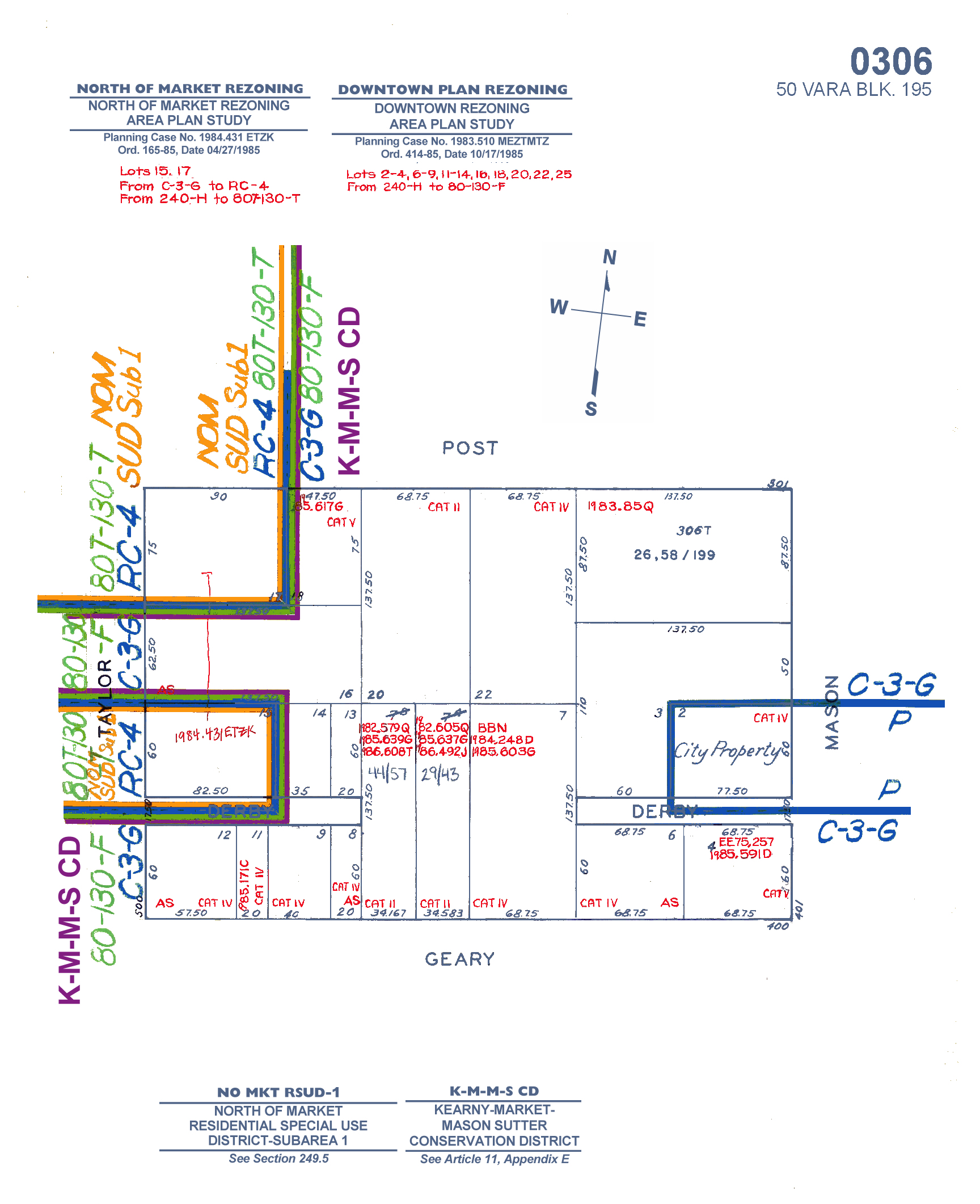

Thought these Sanborn maps were interesting, especially how empty the block still was in 1913.

1913 Sanborn Map, Library of Congress | 1950 Sanborn Map, Library of Congress

Gotta admit I don't really understand these block maps, but I found them so here.

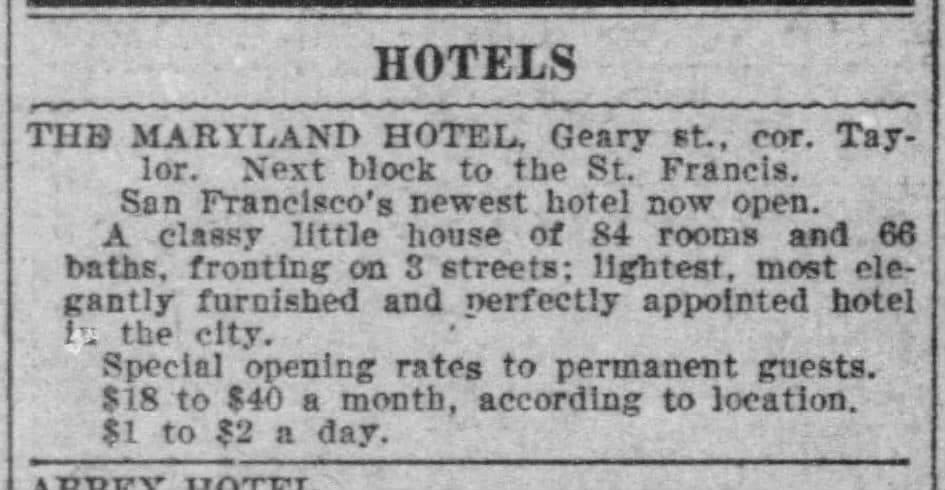

Ads for rooms in the Maryland from 1912 to 1980.

1912 | 1913 | 1927 | 1938 | 1967 | 1978 | 1980

Other Righetti & Headman buildings include the Angelus Apartments, 303 Sacramento Street, and the Calvert Hotel Apartments on Bush.

The tagline, "No Hills To Climb", cracks me up.

Member discussion: