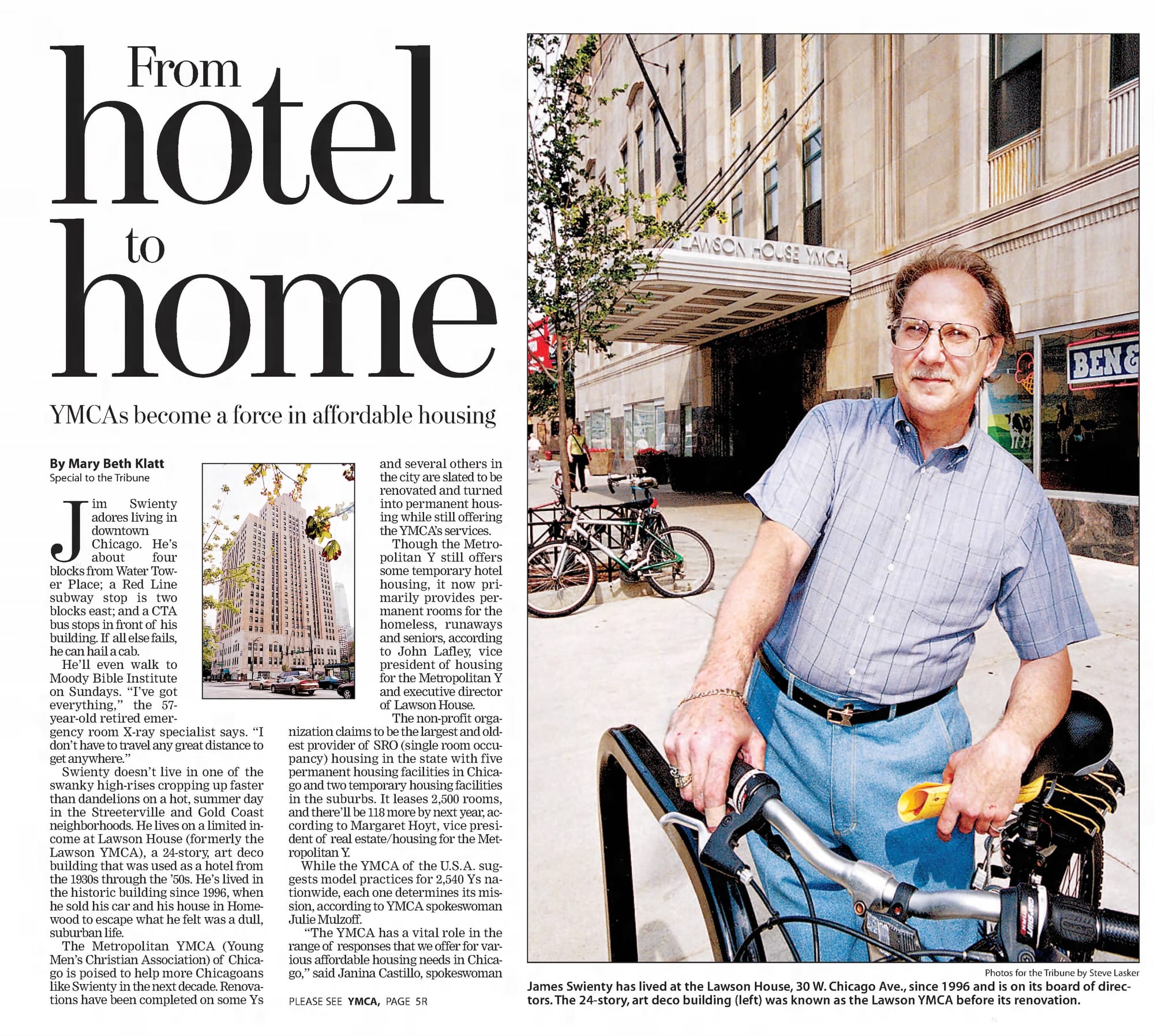

Once the crown jewel of the Chicago YMCA system, a landmark of gay life in the city, and an SRO that provided flexible housing for decades, today the Lawson House is an encouraging story of architectural and (more importantly) affordable housing preservation.

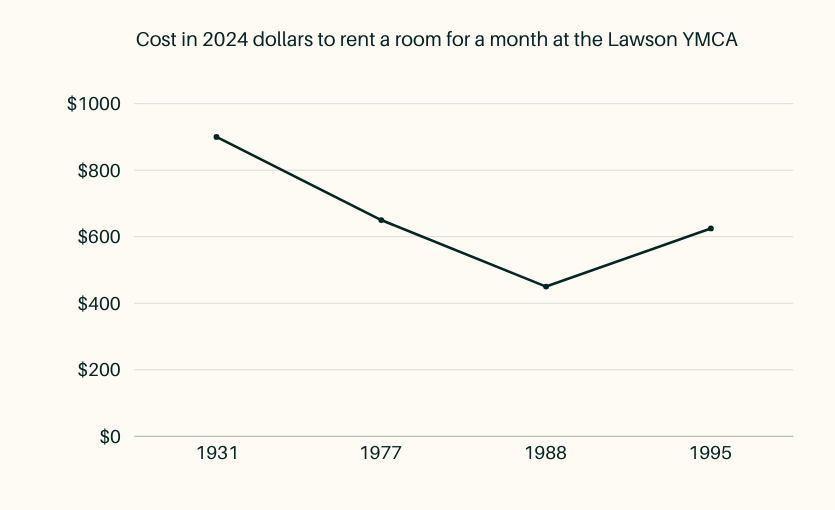

A brawny Art Deco tower designed by Perkins, Chatten & Hammond, the Lawson YMCA opened in 1931 as a 650 room residential hotel with a top-tier membership gym. Stigmatized like the rest of SROs and struggling with decades of deferred maintenance–in the late 1980s nearly 20% of the rooms here were too degraded to rent out–the Lawson YMCA survived partially because it was too big to fail, with the threat of more than 500 residents ending up on the street enough for the city to step in and subsidize a renovation that stabilized the building in the 1990s.

The YMCA eventually handed the building over to developer Holsten Real Estate Development Corporation for $1 on the condition it be retained as affordable housing for 50 years (let's check back in in the 2040s), and after a gut rehab a renewed Lawson House reopened this year as a 409 unit affordable and supportive housing complex. Underlining how complicated funding these affordable projects can be (and thus expensive to finance), the revitalization of the Lawson House relied on a byzantine stack of tax credits, loans, and grants from a mess of agencies and organizations, including the largest single allocation of LIHTC (Low Income Housing Tax Credits) funding in Illinois history. The end result is worth it, but man we gotta figure out a way to make this simpler–hopefully the city’s new affordable housing and development bond helps these projects pencil faster and cheaper.

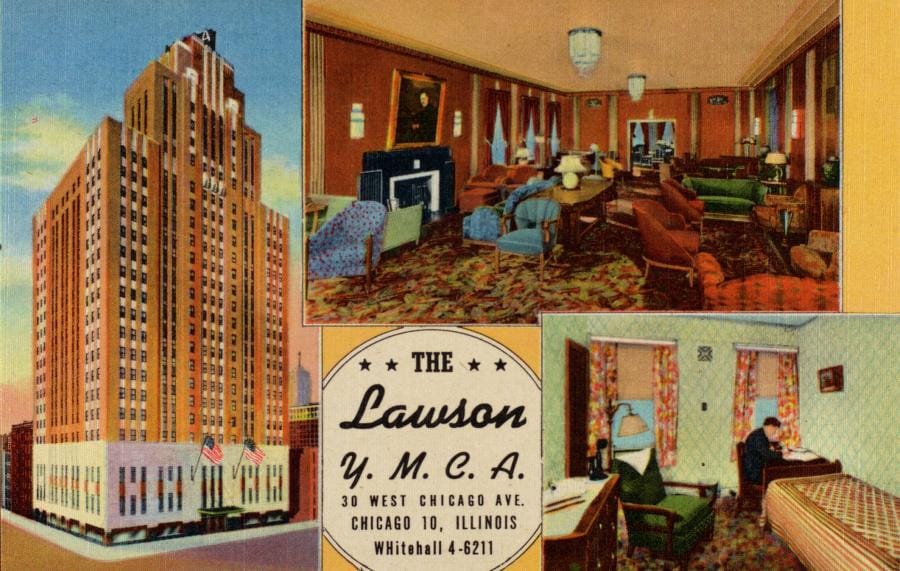

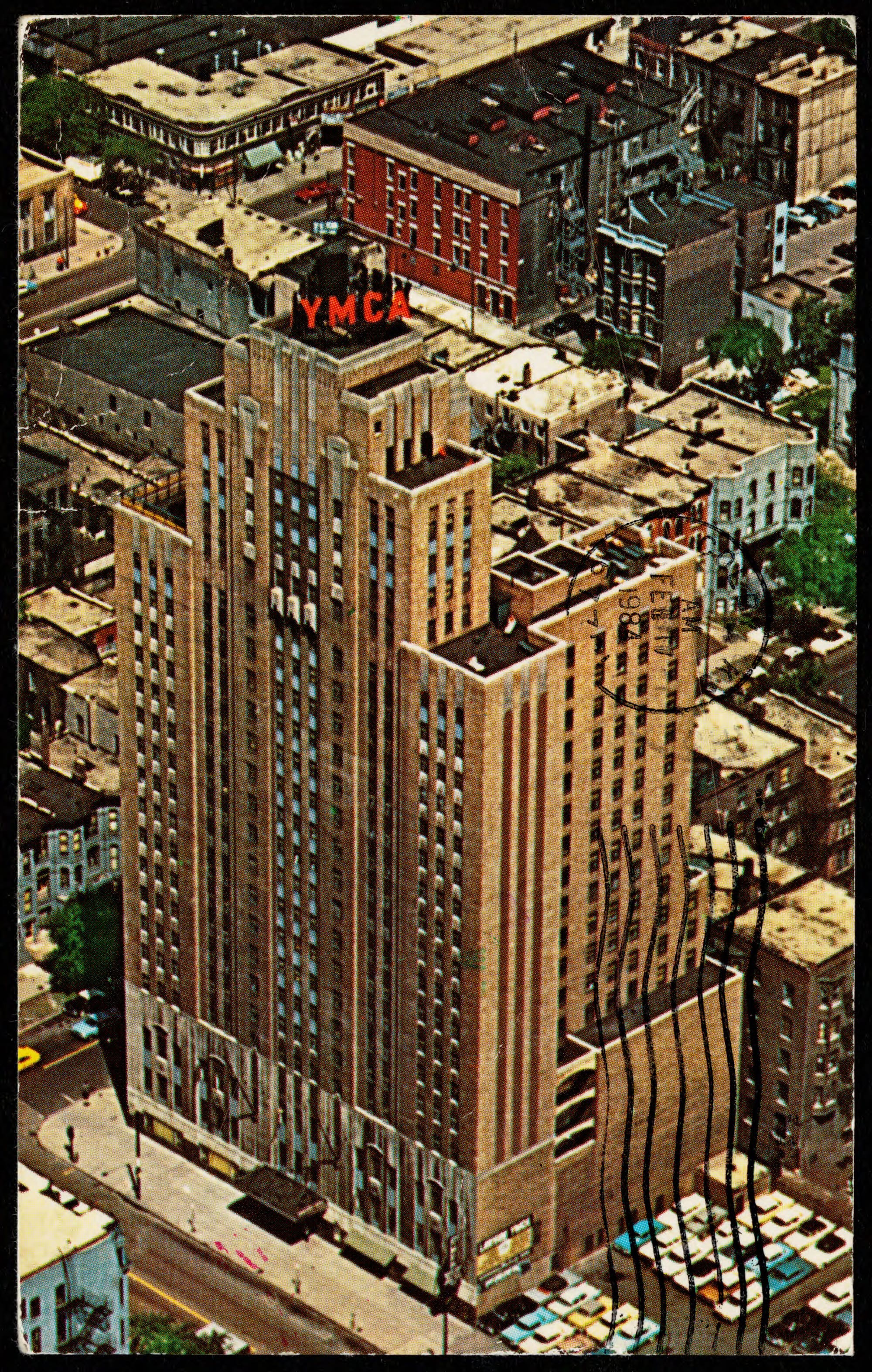

So, what’s changed? Bravo to the team that worked on the renovation–Farr Associates Architecture & Urban Design, Walsh Construction, Holsten, etc.–because the Lawson House looks just as good today as it did in this aspirational 1942 postcard. Seriously, it looks exactly as it did in its heyday, the only real changes from this perspective are:

- The removal of the massive YMCA sign on the building’s roof (naturally, it’s no longer a YMCA).

- The Chicago flag flies alongside the US flag above the front entrance (makes sense, feels like the vigorous embrace of the city flag is a relatively modern phenomenon).

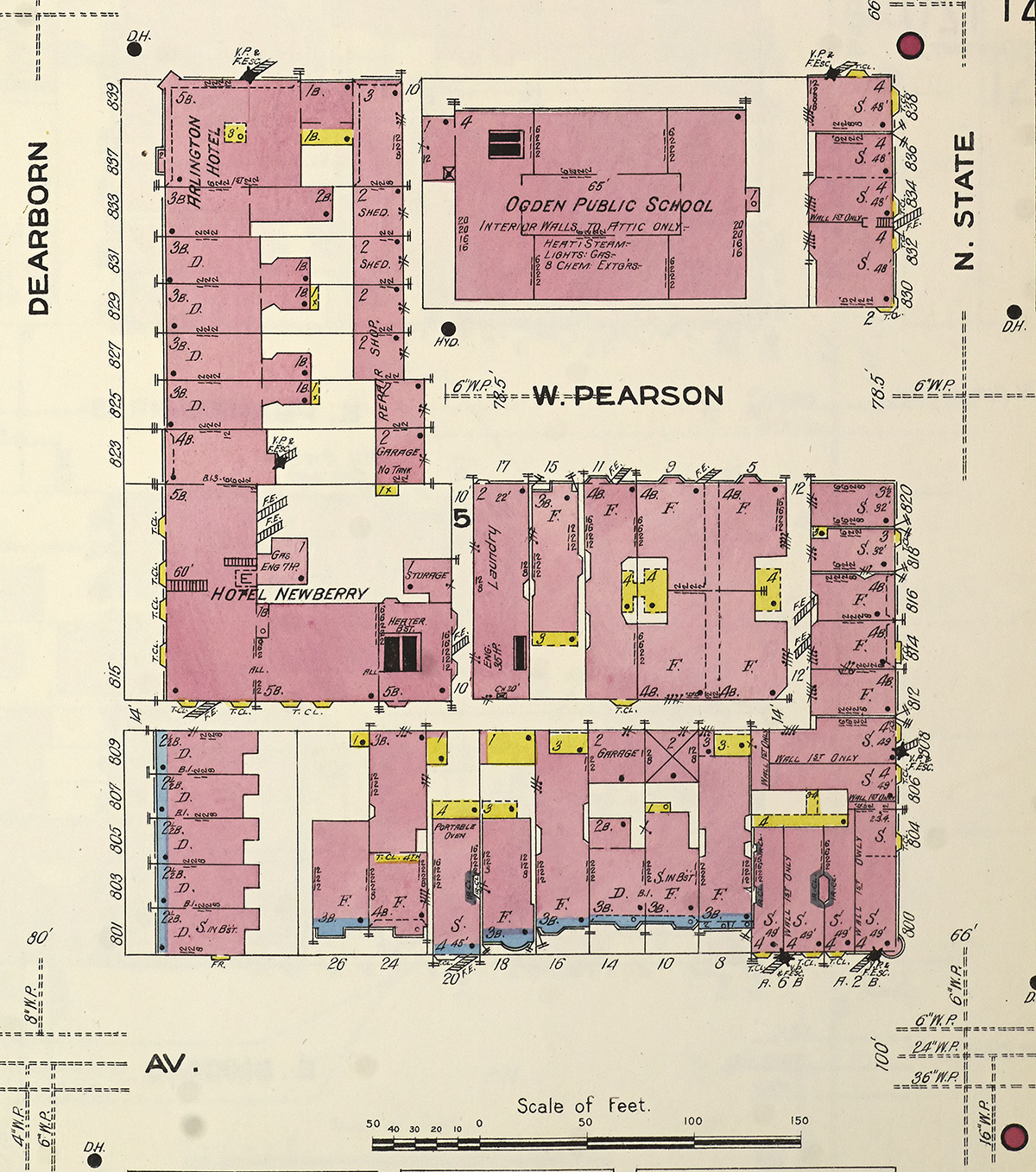

- Some of the Lawson’s neighbors have since been torn down, most notably the old Newberry Hotel just to the north (left), which was replaced with a parking lot (of course).

- A bus lane! (half-assed but still, hell yeah)

The Young Men's Christian Association grew rapidly across the US in the first decades of the 20th century, developing a vast infrastructure of housing, gyms, and education for Evangelical men. In Chicago, Chicago Daily News publisher Victor L. Lawson goosed that development with a $3.5m bequest when he died in 1925, a gift worth more than $60m in 2024 dollars. By 1927, a 900 room addition to the YMCA Hotel on Wabash had turned it into the second-largest hotel in town, but growth was so exuberant that only two year later the YMCA of Metropolitan Chicago made plans for a massive new hotel and administrative headquarters on Chicago Avenue–named for the benefactor whose bequest helped finance it.

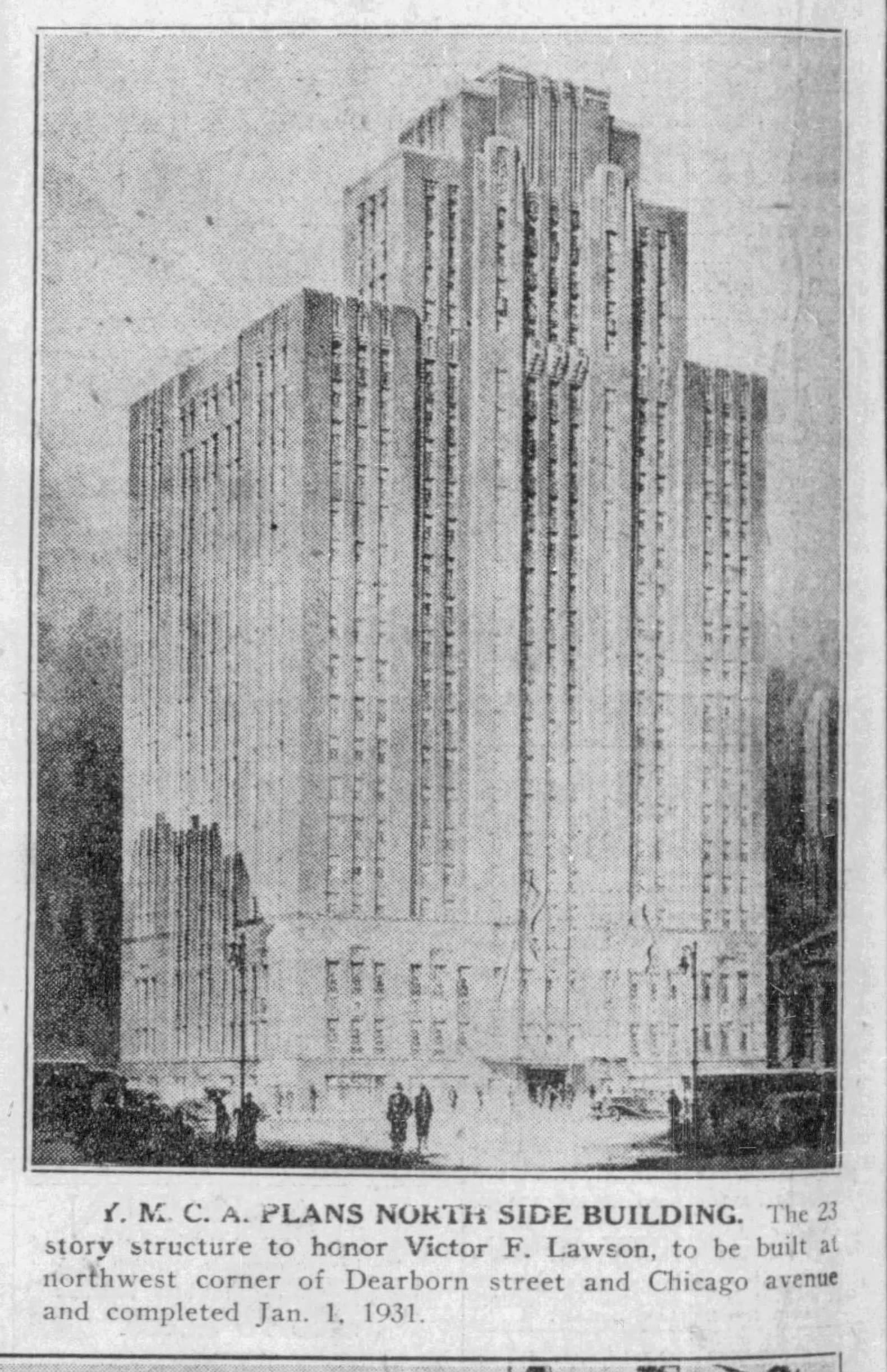

Site selected, Chicago Tribune, 1929 | Rendering, Chicago Tribune, 1929 | Y Ready to Open, Site selected, Chicago Tribune, 1931

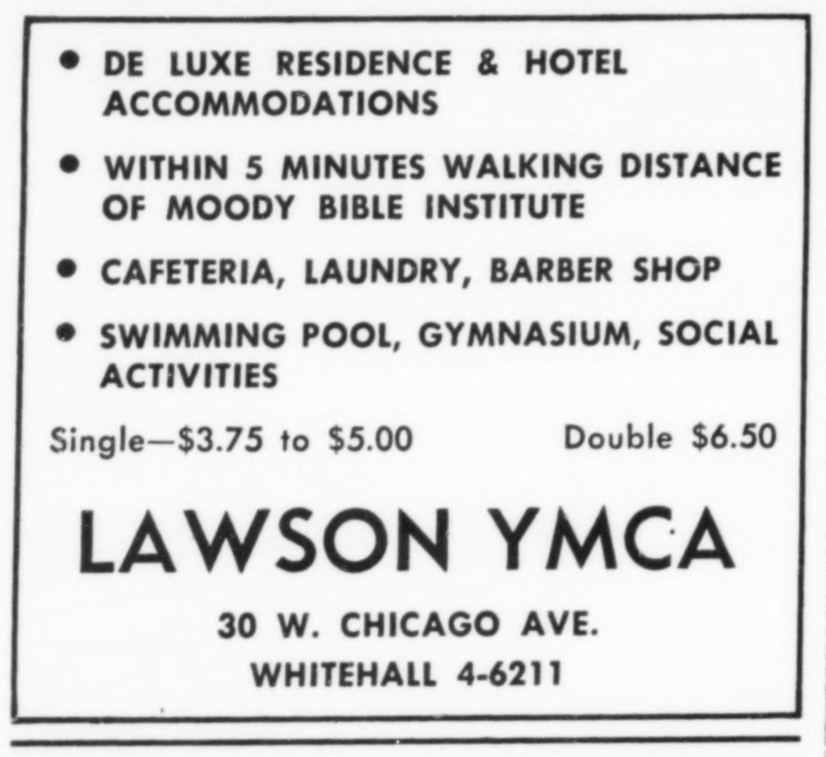

The YMCA envisioned the Victor L. Lawson Memorial YMCA as their flagship Y. Unlike the housing niche it would fill in its later years, the YMCA intended the Lawson to appeal to young professional men with white-collar jobs or upwardly-mobile students. They saw a big market for it in the neighborhood, with more than 25,000 unmarried people living in boarding houses on the Near North Side. The Lawson YMCA would have a chapel, gymnasium, handball courts, club rooms, swimming pool, cafeteria, shooting range, barbershop, dry cleaner, auditorium and roof garden–not just housing for 600+ ambitious evangelicals, but also one of the most well-appointed membership gyms in the city.

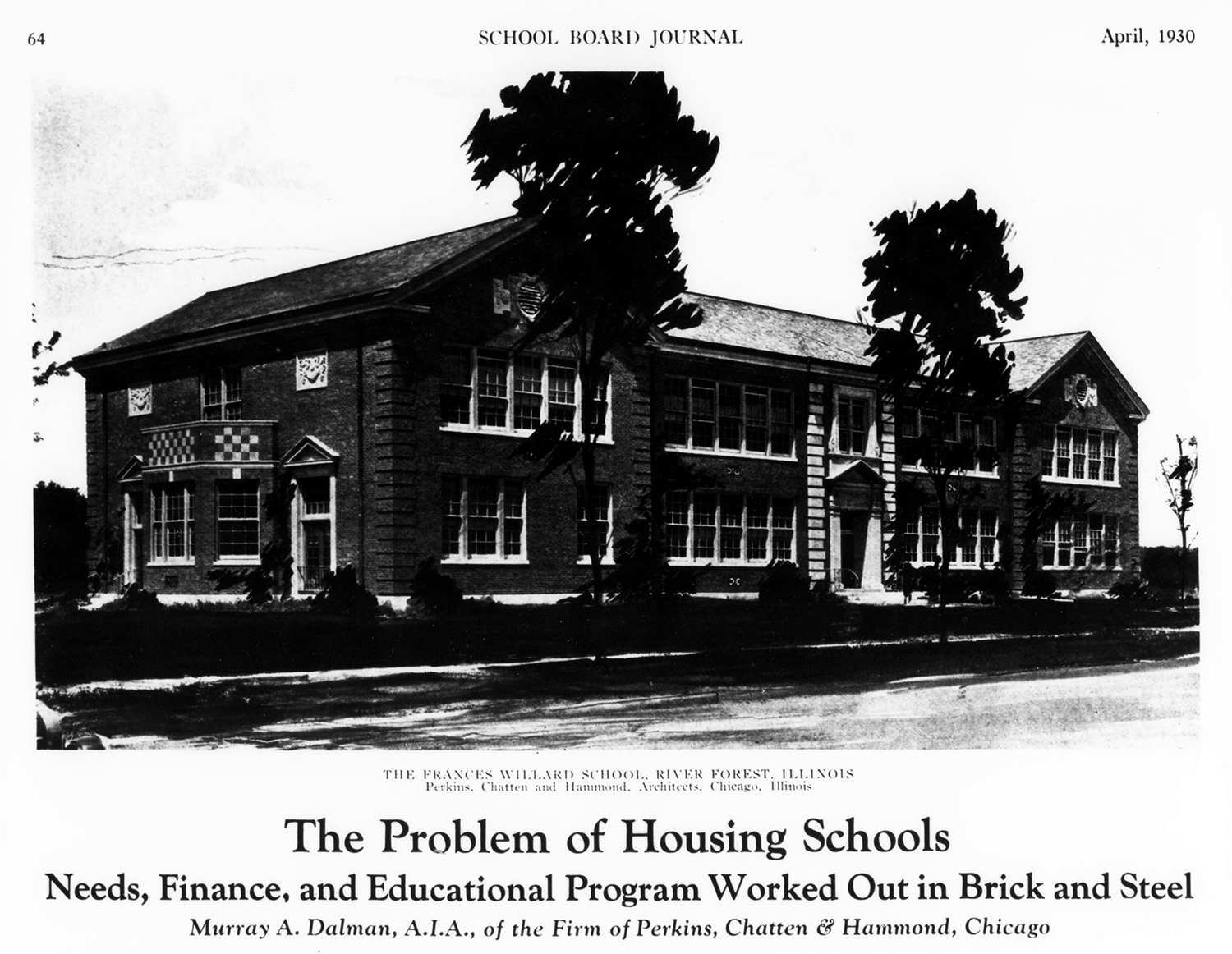

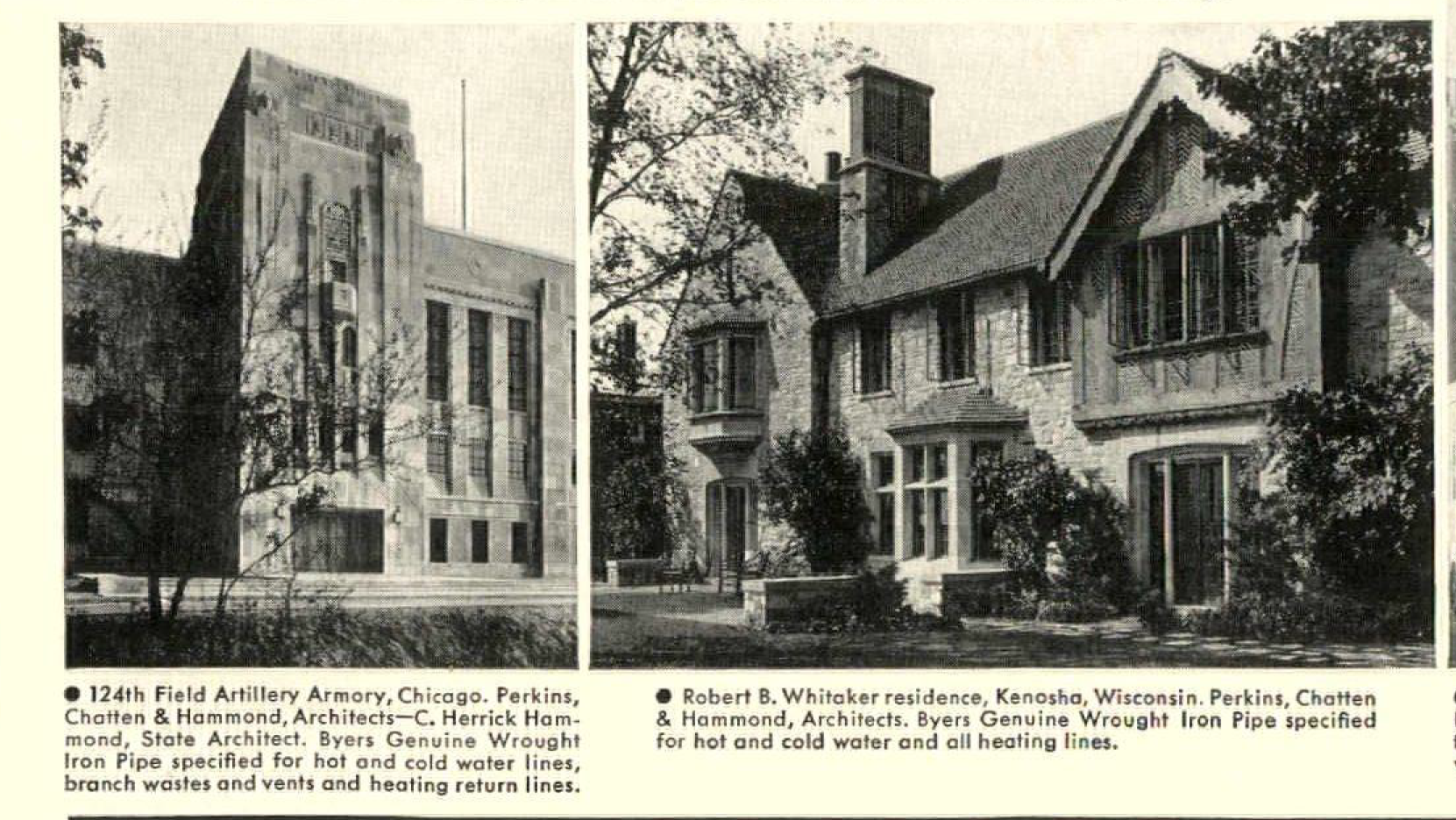

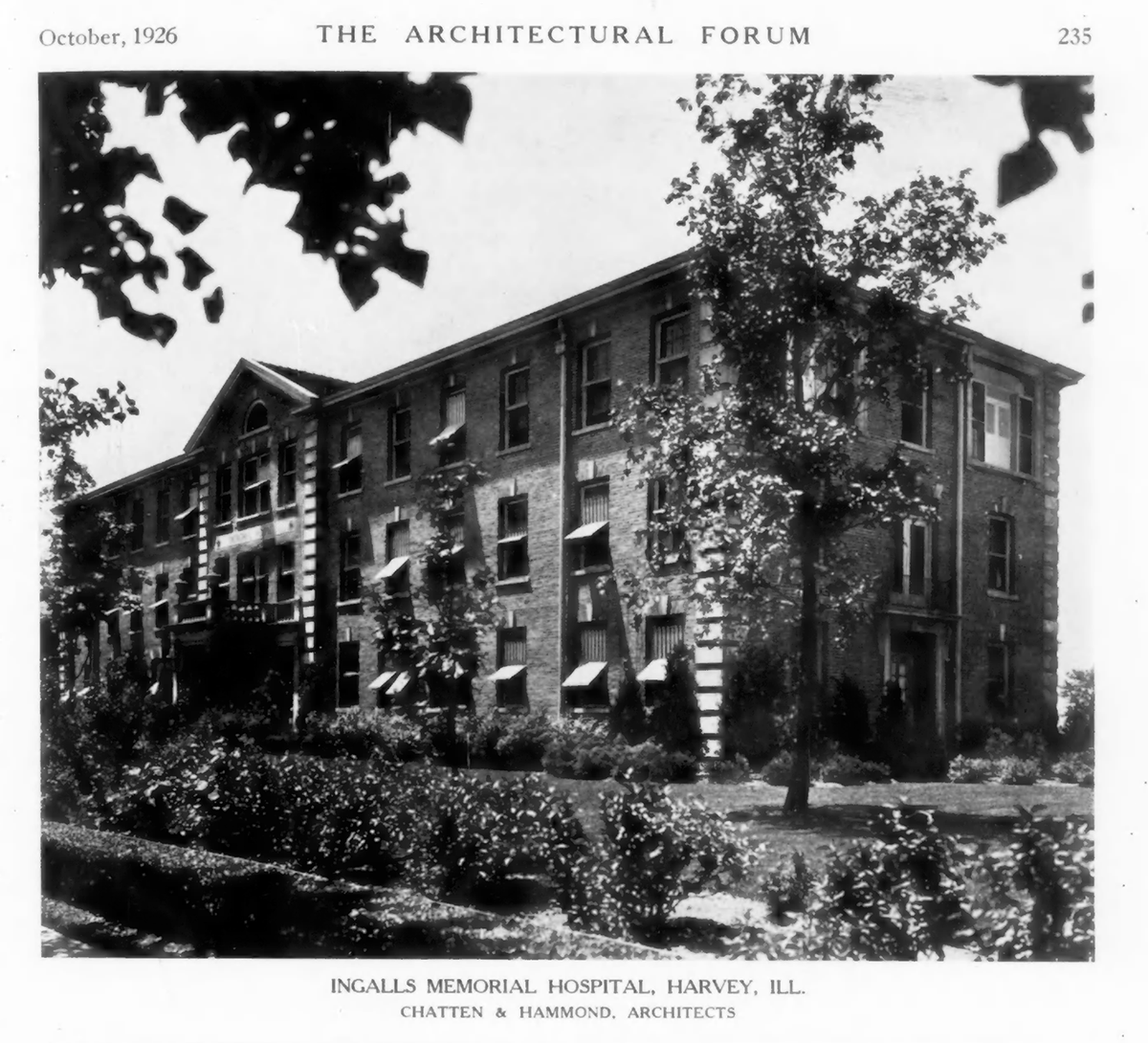

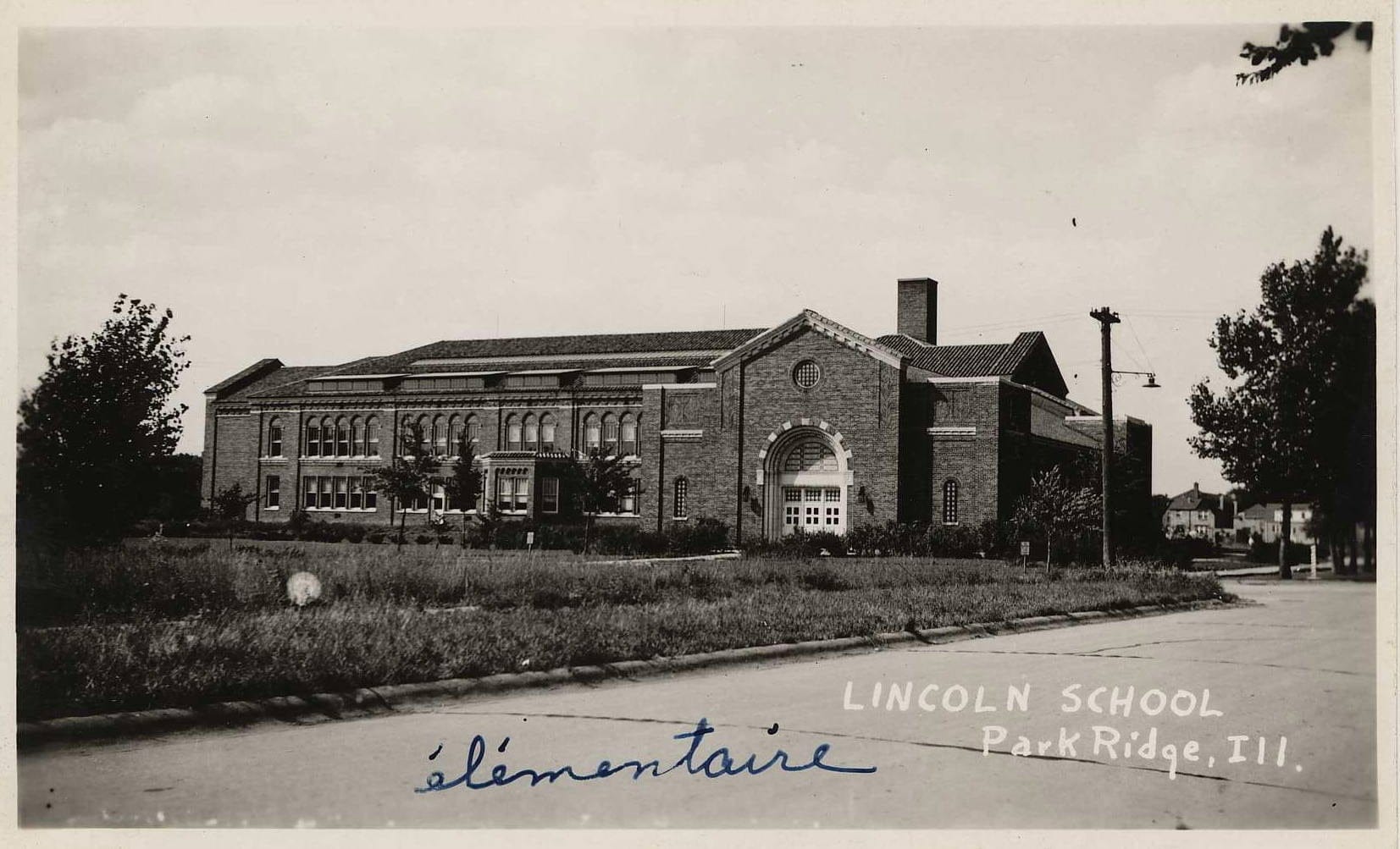

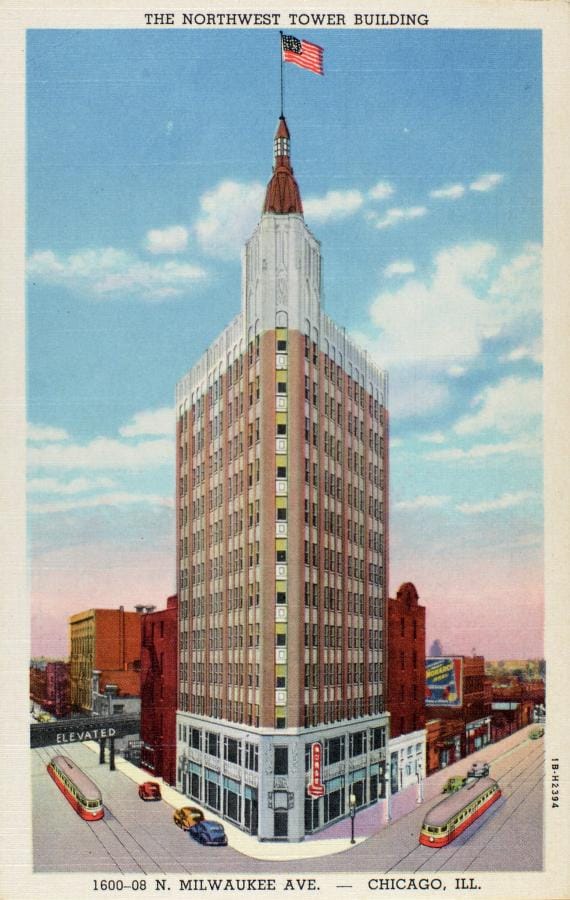

The YMCA of Metropolitan Chicago hired Perkins, Chatten & Hammond to design their new prestige Y. The Perkins here was Dwight Perkins, one of Chicago’s most inspiring architects and the progressive designer of Prairie Style schools and civic buildings. In theory, Perkins, Chatten & Hammond aimed to combine Melvin C. Chatten and C. Herrick Hammond’s expertise in industrial and commercial work with Perkins’ vision and name–in its six years of existence, the firm designed Chicago schools, the Jones Armory, the Lakeview and Duncan Hall YMCAs, and the Northwest Tower in Wicker Park (now the Robey Hotel). By this point, though, Dwight Perkins’ career was winding down and according to his son (Perkins + Will founder Larry) the firm’s non-school work “weren’t very much dad’s”, so it sounds like the Lawson YMCA was mostly Chatten & Hammond’s work.

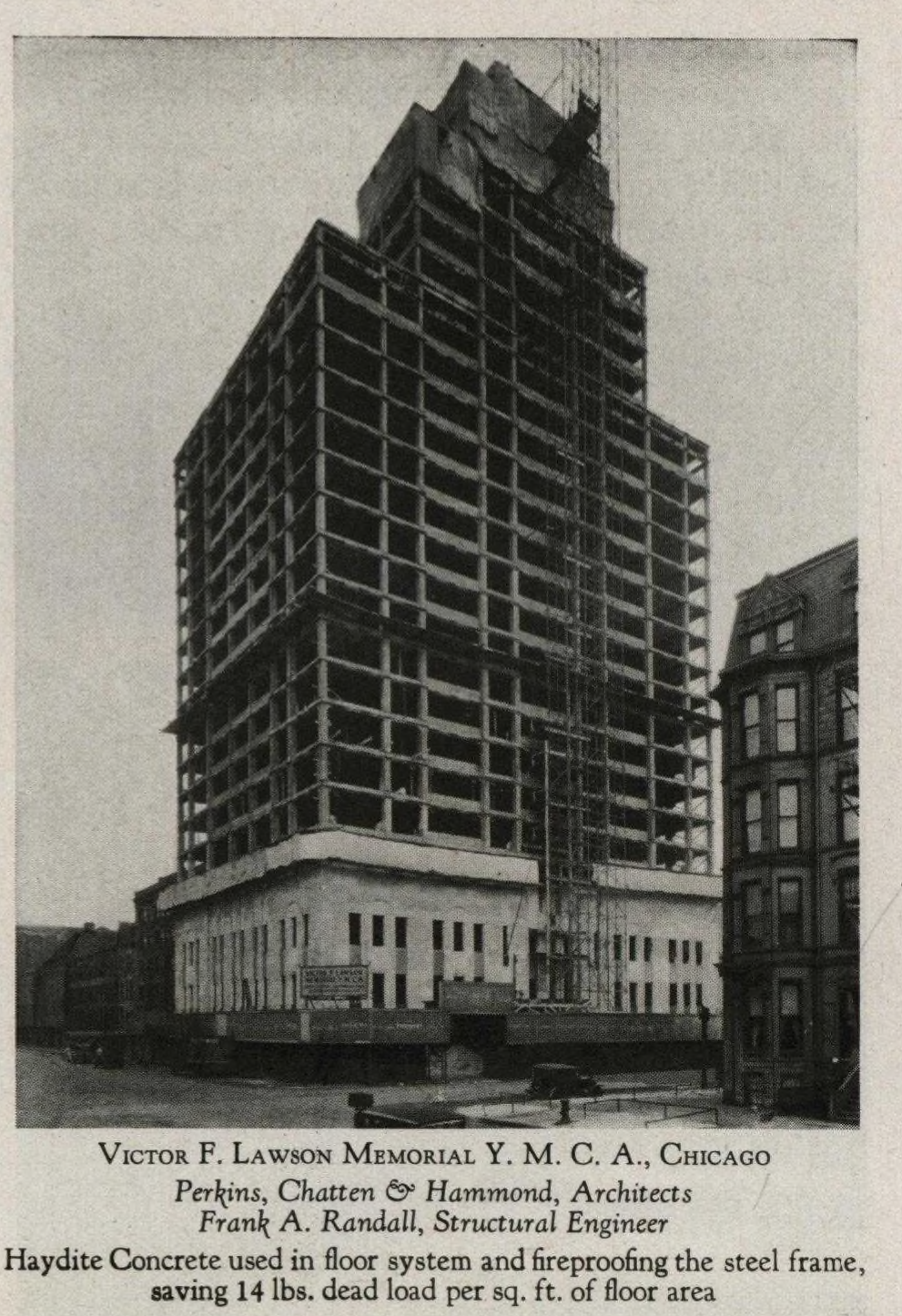

Construction photo, 1940, Haydite Catalog, the Internet Archive | Drinking fountain ad, Architecture, 1932 | Glass ad, Architecture, 1932 | Undated, UIC via Chicago Collections | ~1932, UIC via Chicago Collections | postcard | 1970s, Illinois State Historic Preservation Office | 1969, Richard Nickel, Art Institute of Chicago via Chicago Collections | C. Willem Brubaker, 1976, UIC via Chicago Collections

It certainly wasn’t conceived as one, but the construction here acted as a small-scale, de facto jobs program in the early years of the Great Depression, with the YMCA powering through construction as private sector construction ground to a halt after 1930. Limestone, golden-tan brick, and terracotta, the end result is a burly Art Deco monolith–particularly neat is the chapel, with stained glass windows by the brilliant Edgar Miller. The YMCA dropped the requirement that residents have affiliation with an evangelical church in 1931, the year the Lawson Y opened, and the building quickly became a bustling part of the Chicago city fabric, as a place to live, a place to learn, and a place to work out at.

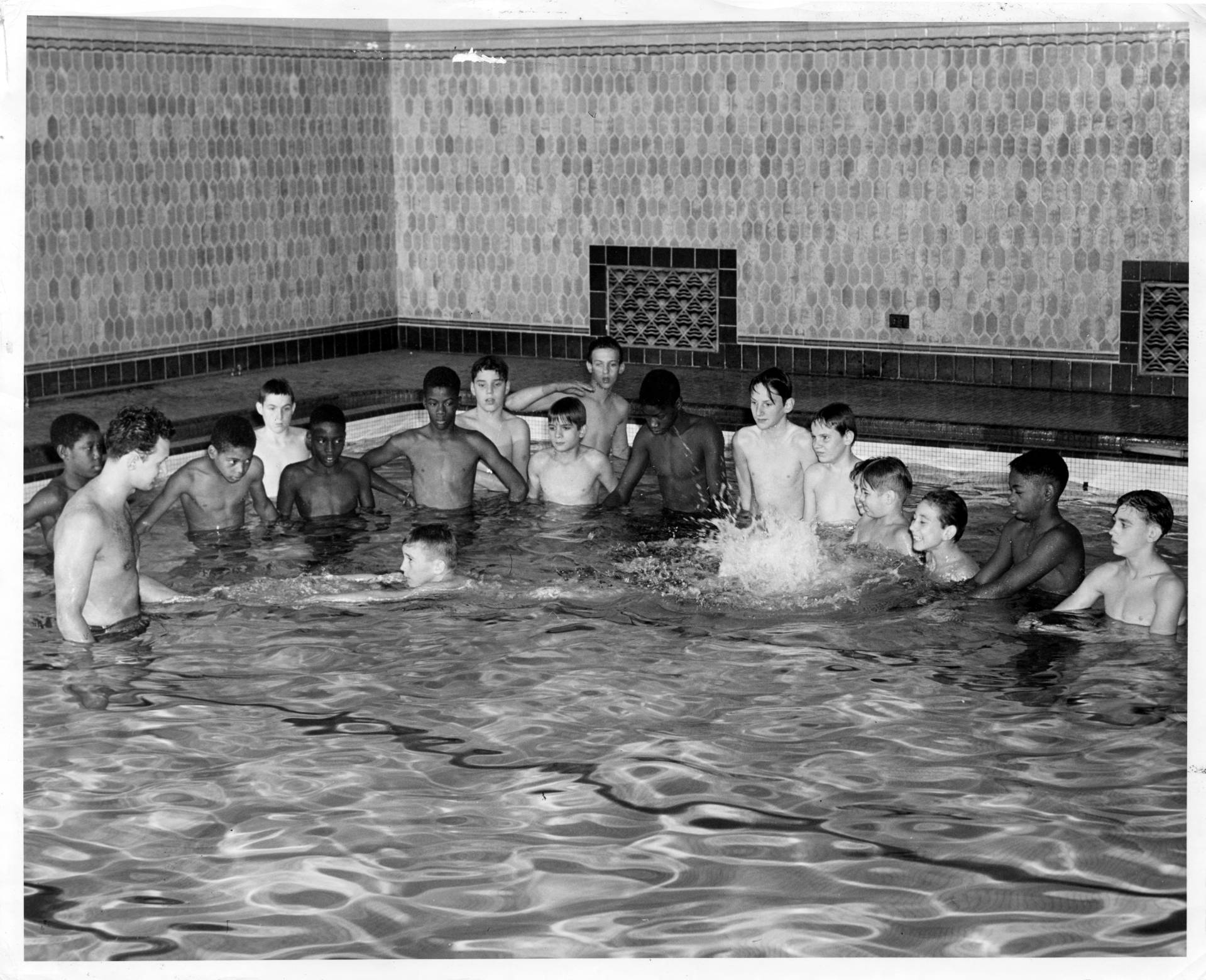

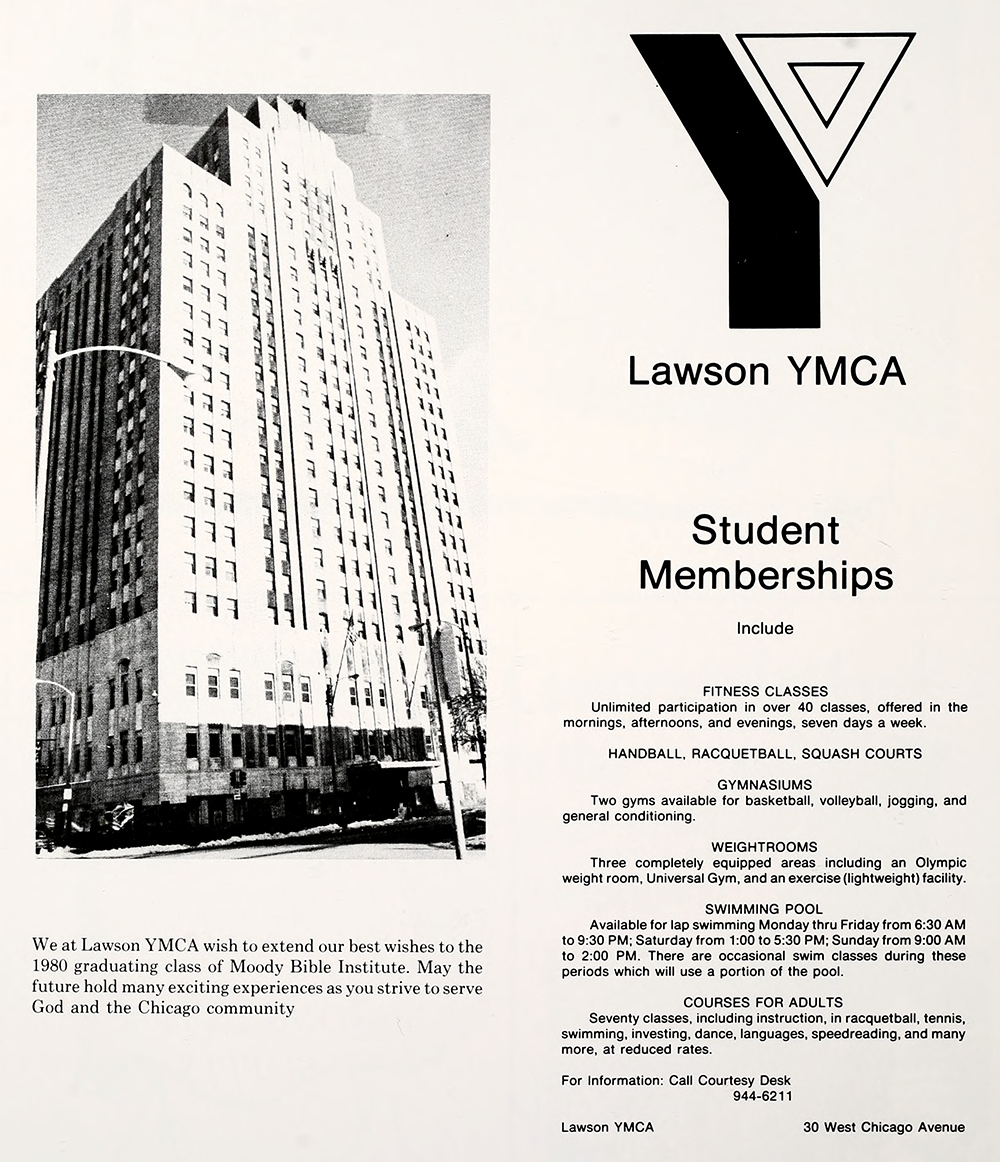

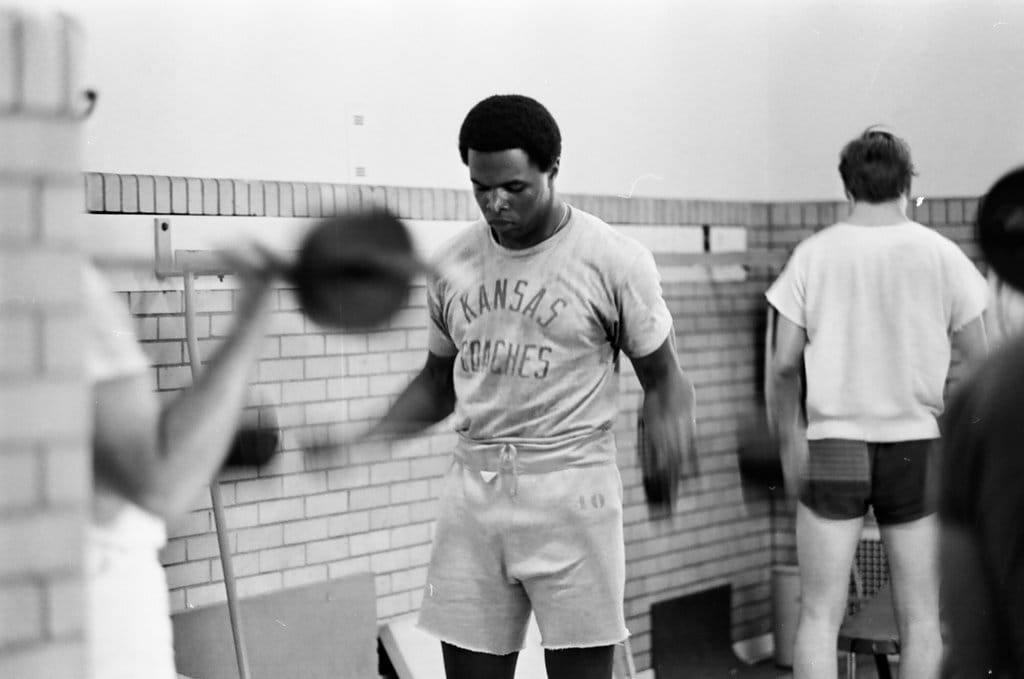

Swimming lessons, 1951, AG Falk, University of Minnesota | 1980 gym ad, Arch, Moody Bible School, the Internet Archive | Gale Sayers working out in the gym, Dave Fornell, ST-50000151-0027, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum | 1955 gym ad, Chicago Tribune

Like any building this full of life, the Lawson YMCA picked up a whole lot of names to drop over the years. Comedian Phyllis Diller worked as a cashier in the cafeteria here, Bears Hall-of-Famer Gale Sayers trained in the gym, cartoonist Bill Mauldin lived here, the 1960s Chicago Bulls did their preseason here…the list could go on.

International Mr. Leather could also be on that list–IML founders Chuck Renslow and Dom Orejudos ran physique competitions at the Lawson Y. Those events helped inspire their Mr. Gold Coast competition at their leather bar, which eventually lead to the granddaddy of all leather events.

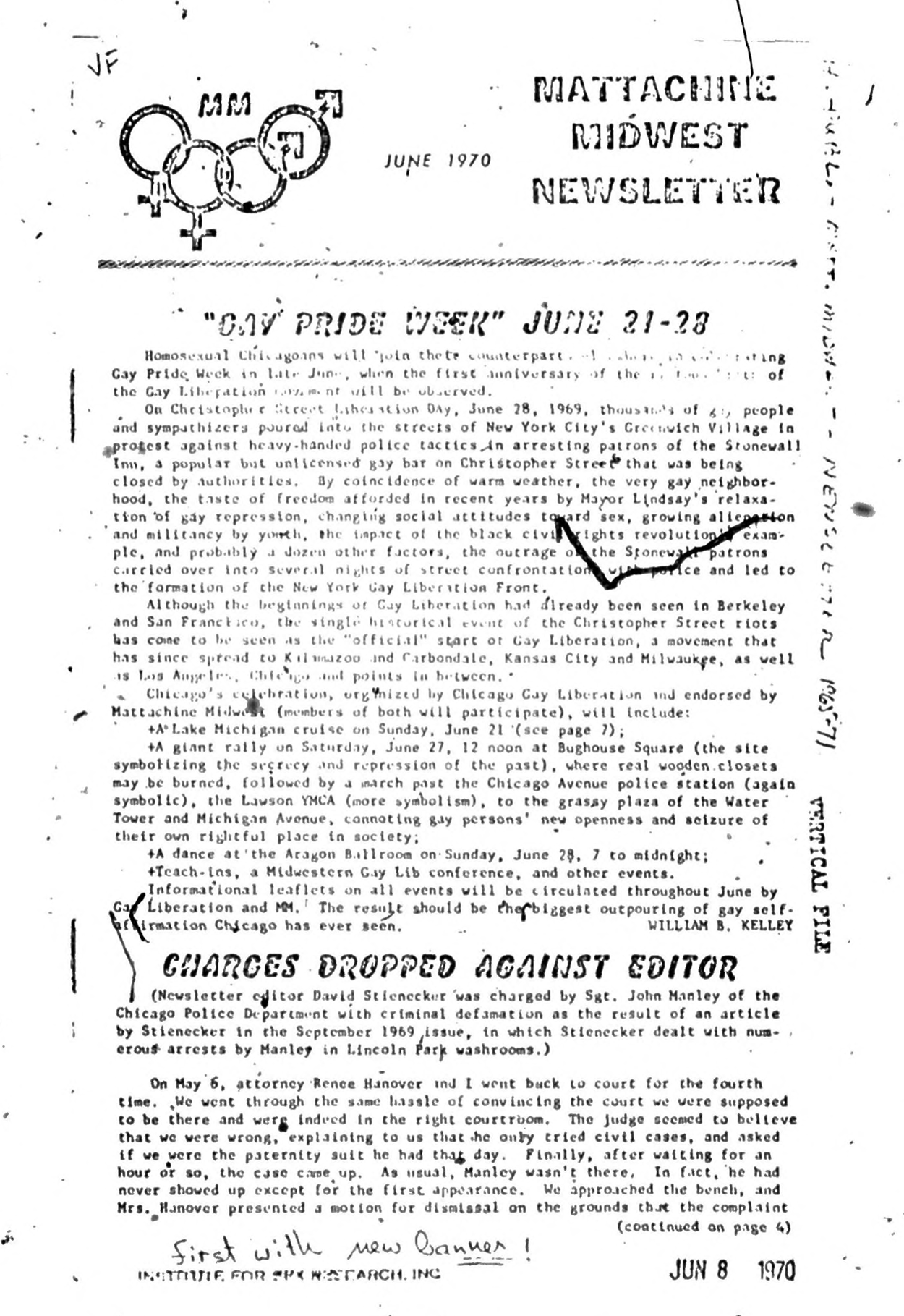

The Lawson YMCA was also a center of gay life in Chicago more generally, especially from the 1940s through the 1970s. Writer Jack Fritscher called it “a sperm-o-rama orgy party from the roof sundeck down through the rooms and toilets” in the 1960s and the Mattachine Midwest newsletter, the monthly publication of Chicago’s first successful gay rights organization, called it “the Lawson Y of infamous memory”. During Gay Pride Week in 1970, the march route intentionally passed the Lawson YMCA as a symbolic nod (as well as the Chicago Avenue police station, underlining the radical politics of a Pride March and the inspiration of Stonewall).

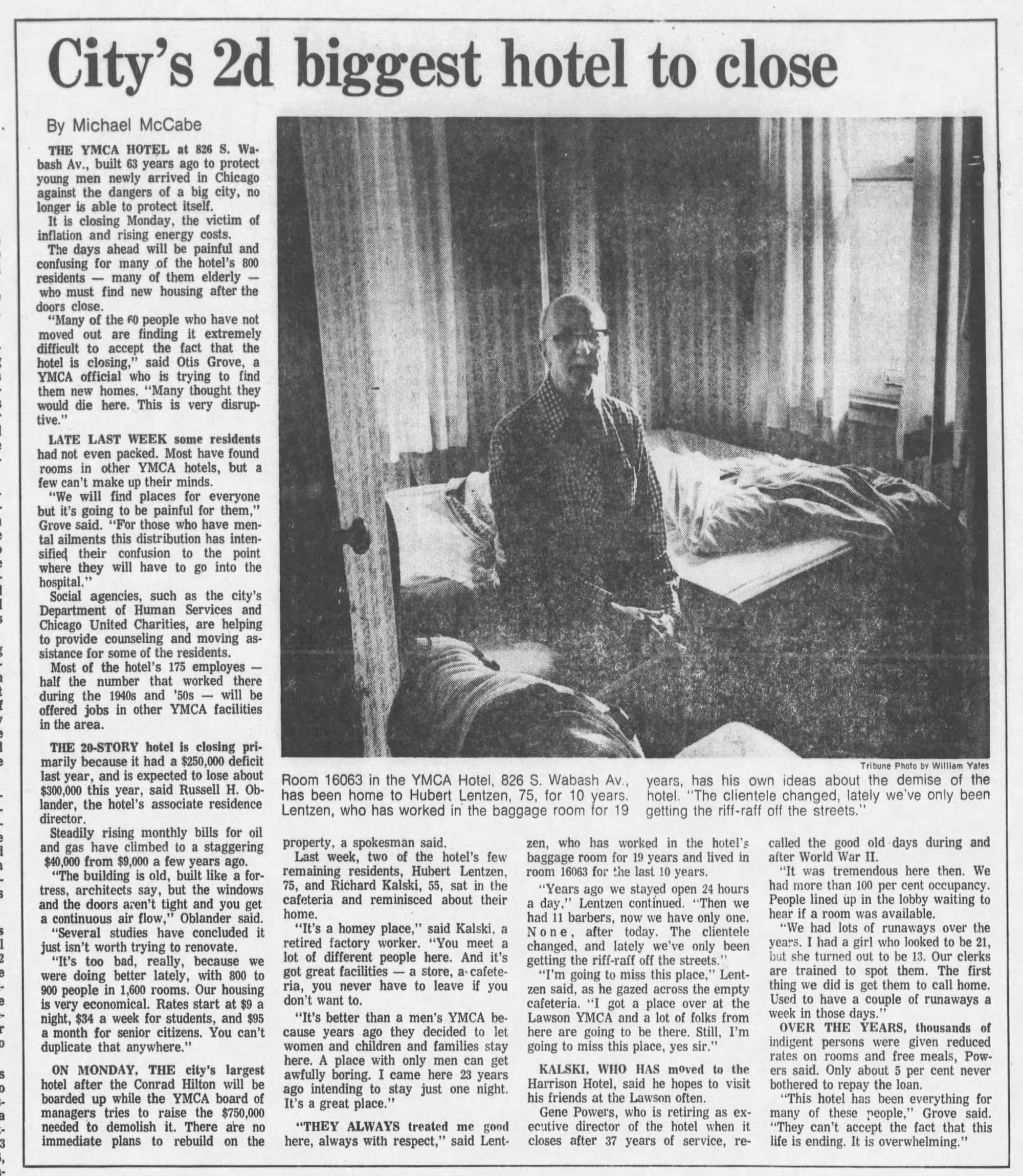

Ultimately what kept people living at the Lawson was its affordability and flexibility, even as residential hotels were stigmatized and neglected, then regulated and redeveloped into near extinction. Chicago lost more than 18,000 SRO rooms from the early 1970s to the late 1980s, including the Lawson’s peer, the massive YMCA Hotel on Wabash. The YMCA sold that one for $5m to a developer who converted it into condos, sending more than 800 residents scrambling for housing.

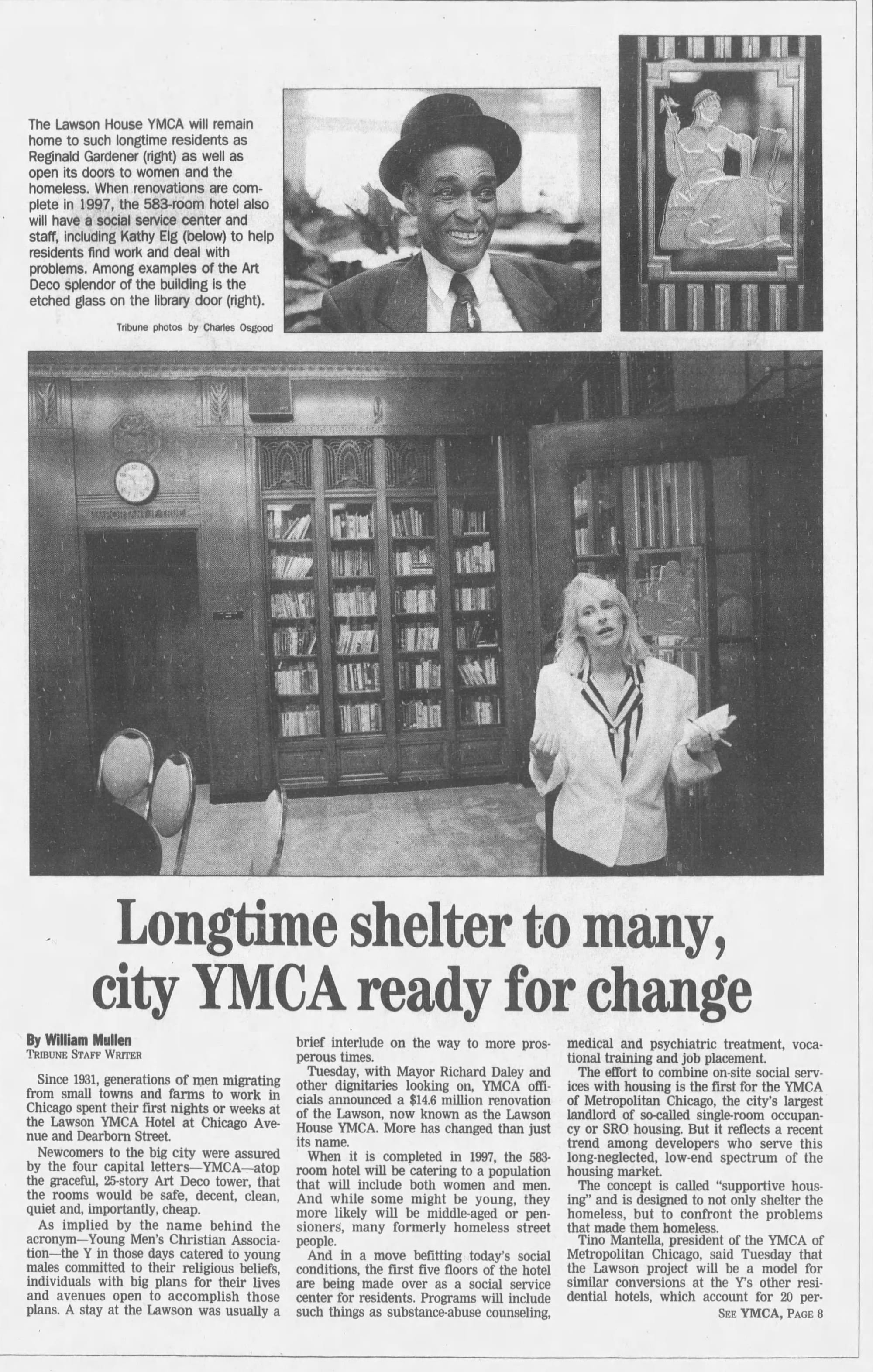

At the Lawson YMCA in 1988, neglect and deferred maintenance meant that more than 115 rooms were out of service out of the building’s ~600. Unable or unwilling to fix the building up, the YMCA growled about selling it to a developer–with the implied threat that hundreds of residents from Chicago’s largest remaining SRO would end up on the street–which frightened the city into granting them $8.6m to help restore the building on the condition the SRO rooms would be leased as permanent affordable housing. That renovation stabilized things before a $14m project from 1995 to 1997 improved things a bit, but the Lawson YMCA was in such poor condition, with so much deferred maintenance, that those efforts mainly stemmed the bleeding rather than truly restoring and modernizing the housing. Residents were ultimately still paying the equivalent of $600 a month for an individual room with a desk, chair, twin bed, closet, sink and mirror, but no private bath or cooking abilities.

1995, Chicago Tribune | 2003, Chicago Tribune

With the YMCA right-sizing its Chicagoland real estate holdings, in 2014 they sold the building for $1 to Holsten Real Estate Development Corporation, with the agreement that Holsten would maintain the building as affordable housing for at least 50 years. To restore the building, Holsten and its development partners put together a complex capital stack that included Low Income Housing Tax Credits, state historic tax credits, HUD HOME Investment Partnerships loans from the city and the Illinois Housing Development Authority, and a loan from ComEd. A 2017 listing on the National Register of Historic Places was undoubtedly used to unlock some of those tax incentives. To subsidize rent for residents, who make between 0 and 60 percent of the Area Median Income, a wholly different mix of vouchers, subsidies, and grants were cobbled together.

Redesigned by Farr Associates Architecture & Urban Design and built by Walsh Construction, the renamed Lawson House reopened in April 2024 with 406 affordable apartments (plus three for live-in building managers). The renovation won a clutch of preservation, restoration, and adaptive reuse awards. Deservedly so–what a great project.

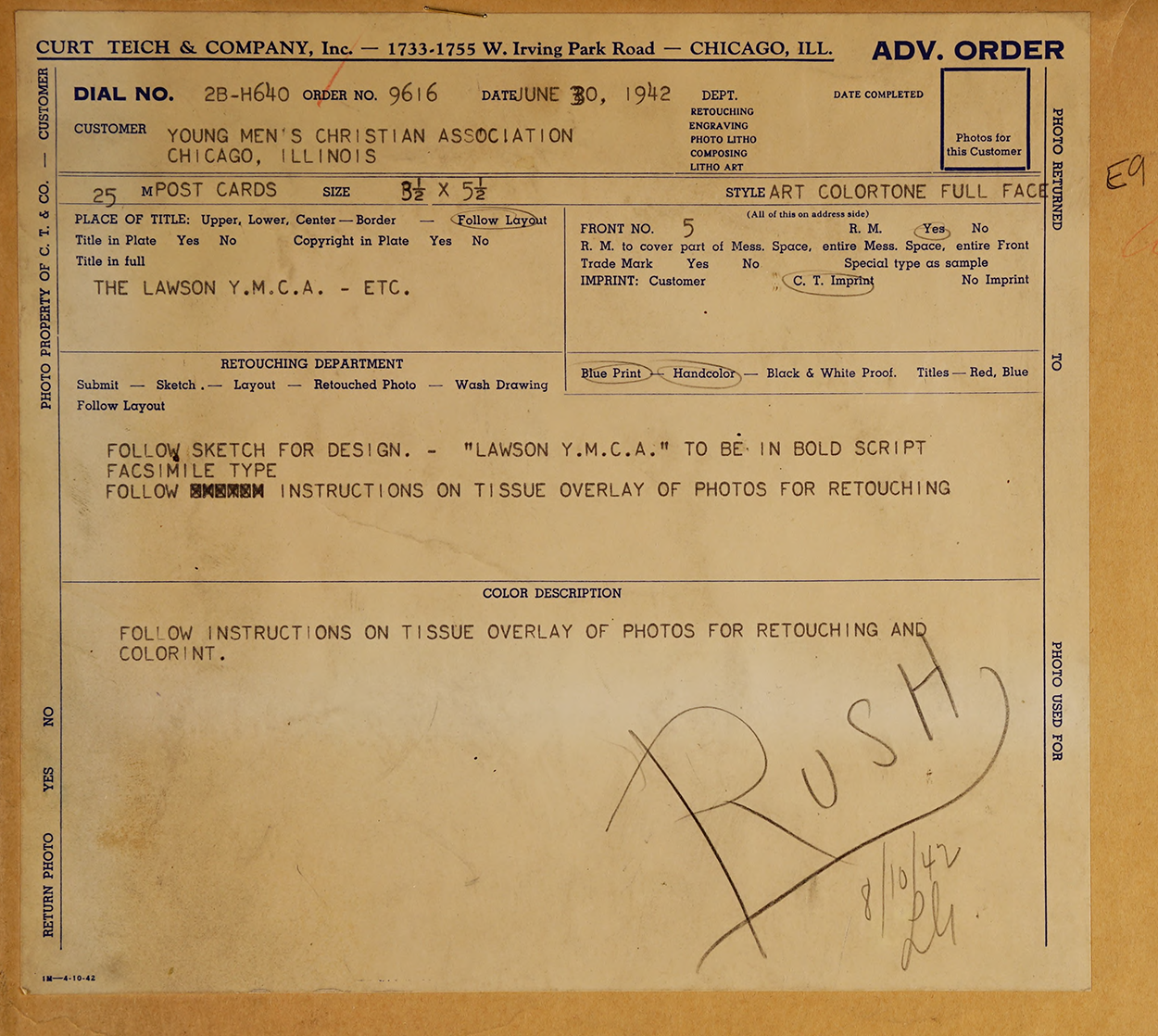

2024 photos, me | 1942 postcard in full, Curt Teich Postcard Archives, Newberry Library

Production Files

Further reading:

- Living Downtown by Paul Groth

- NRHP Nomination Form

- Article in Concrete from 1931 about the concrete here

Six buildings designed by Perkins, Chatten & Hammond. They ultimately only worked together for six years, from 1927 - 1933. When discussing Hammond in his Chicago Architects Oral History, Larry Perkins (Dwight's son, who worked on the Lincoln School project in Park Ridge for his dad) said it, “never would have occurred to me that he knew a drawing from a dish of applesauce”.

Frances Willard School in American School Board Journal, 1930, the Internet Archive | Armory and residence, 1934, Architecture | Ingalls Memorial Hospital in Harvey, 1926, Architectural Forum | Lincoln School in Park Ridge | Northwest Tower in Wicker Park

Lawson House's block over the years, from 1938 to 1995.

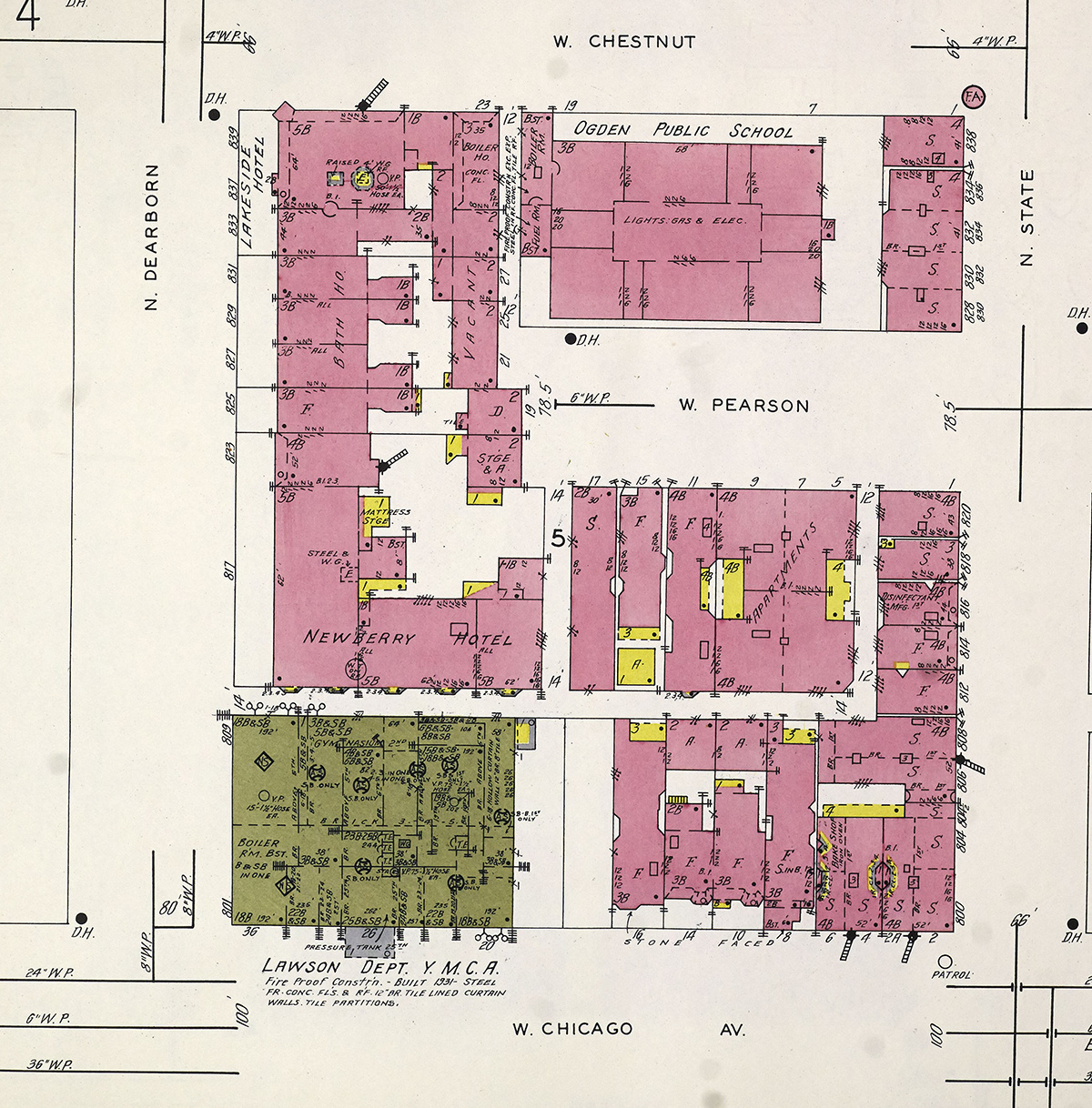

Plus the Sanborn maps, of course. The Lawson YMCA was one of a few hotels on this block, which also had the Newberry and Lakeside. You can also see the parking lots just start to claim surrounding buildings in the 1950 map.

1910 Sanborn Map | 1935 Sanborn Map | 1950 Sanborn Map

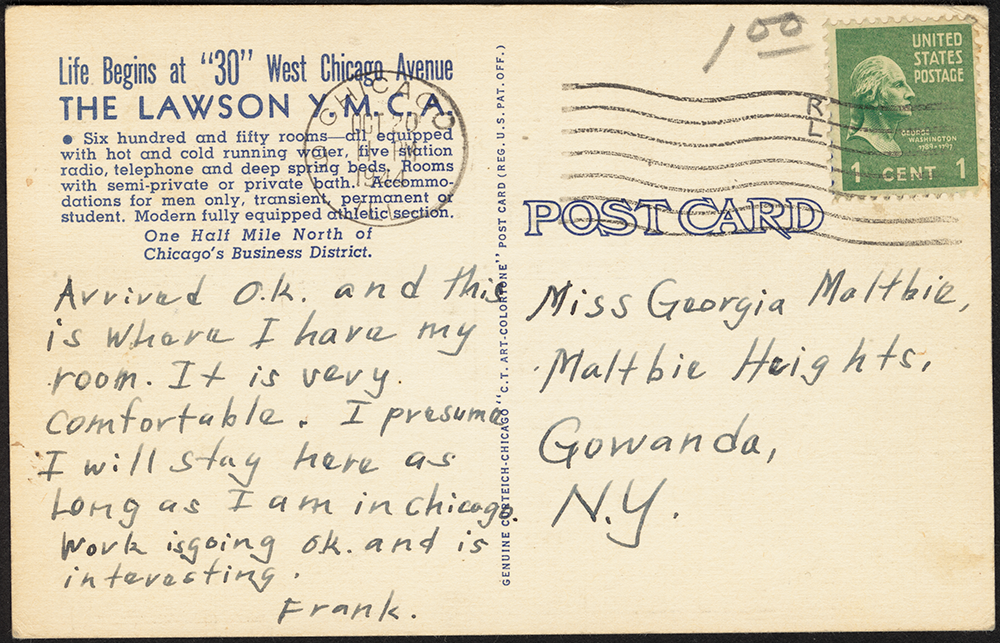

Postcard versos for various Lawson YMCA postcards, including one from the Cliff Smith YMCA Postcard Collection, Digital Commonwealth | 1942 production file, Curt Teich Postcard Archives, Newberry Library via the Internet Archive | Interior Postcard, Cliff Smith YMCA Postcard Collection, Digital Commonwealth | Aerial Postcard, Cliff Smith YMCA Postcard Collection, Digital Commonwealth | Postcard, Cliff Smith YMCA Postcard Collection, Digital Commonwealth

Some of the room ads.

1931 ad | 1954 ad | 1959 ad

I took the present photo from the top of Asbury Plaza's parking garage.

Member discussion: