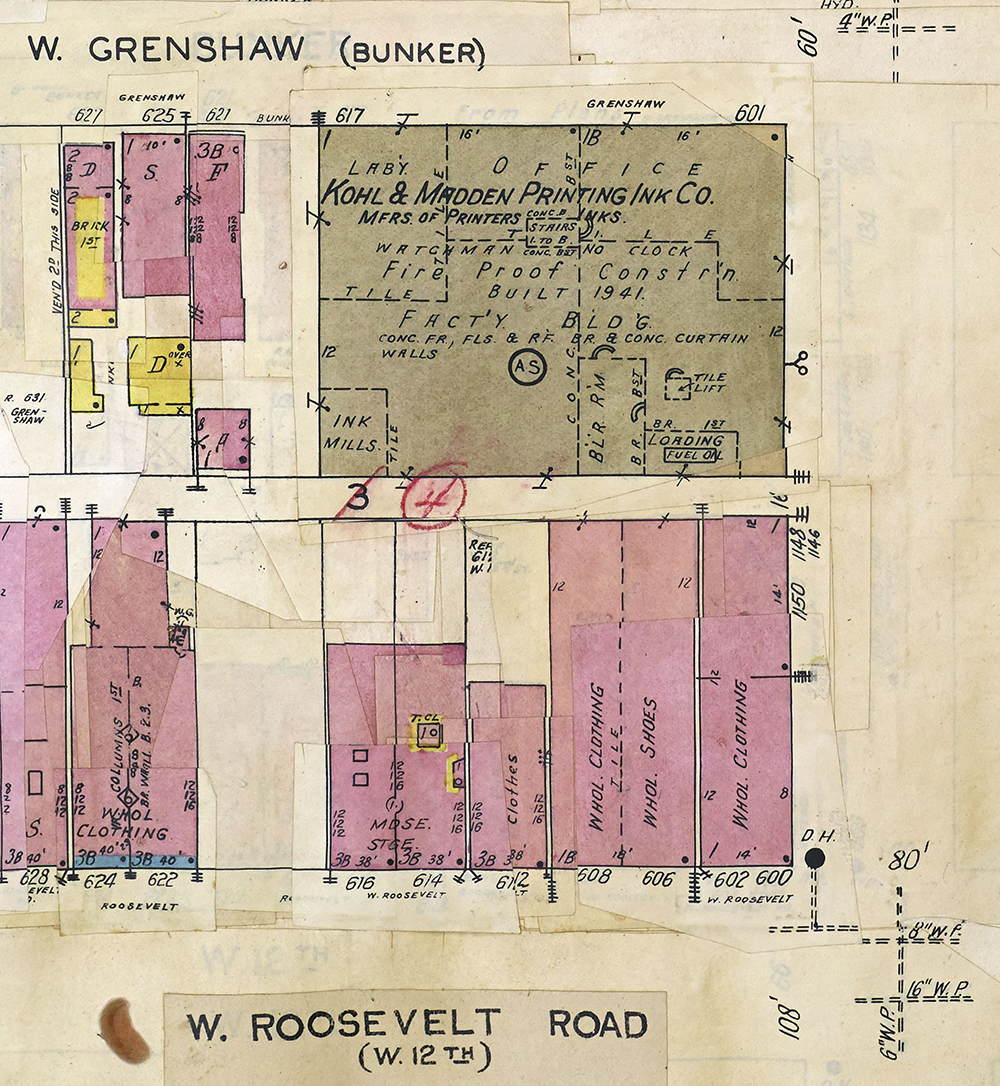

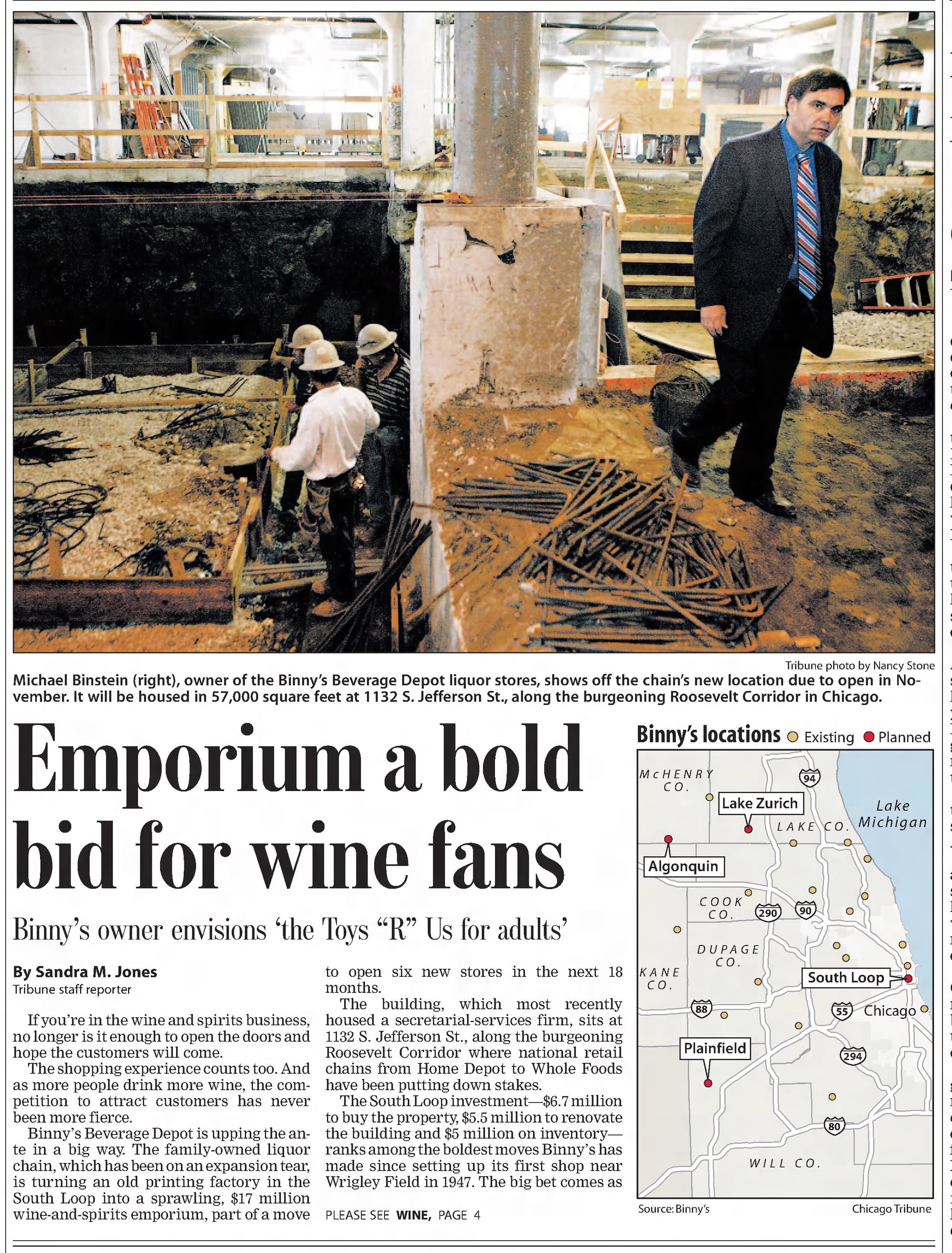

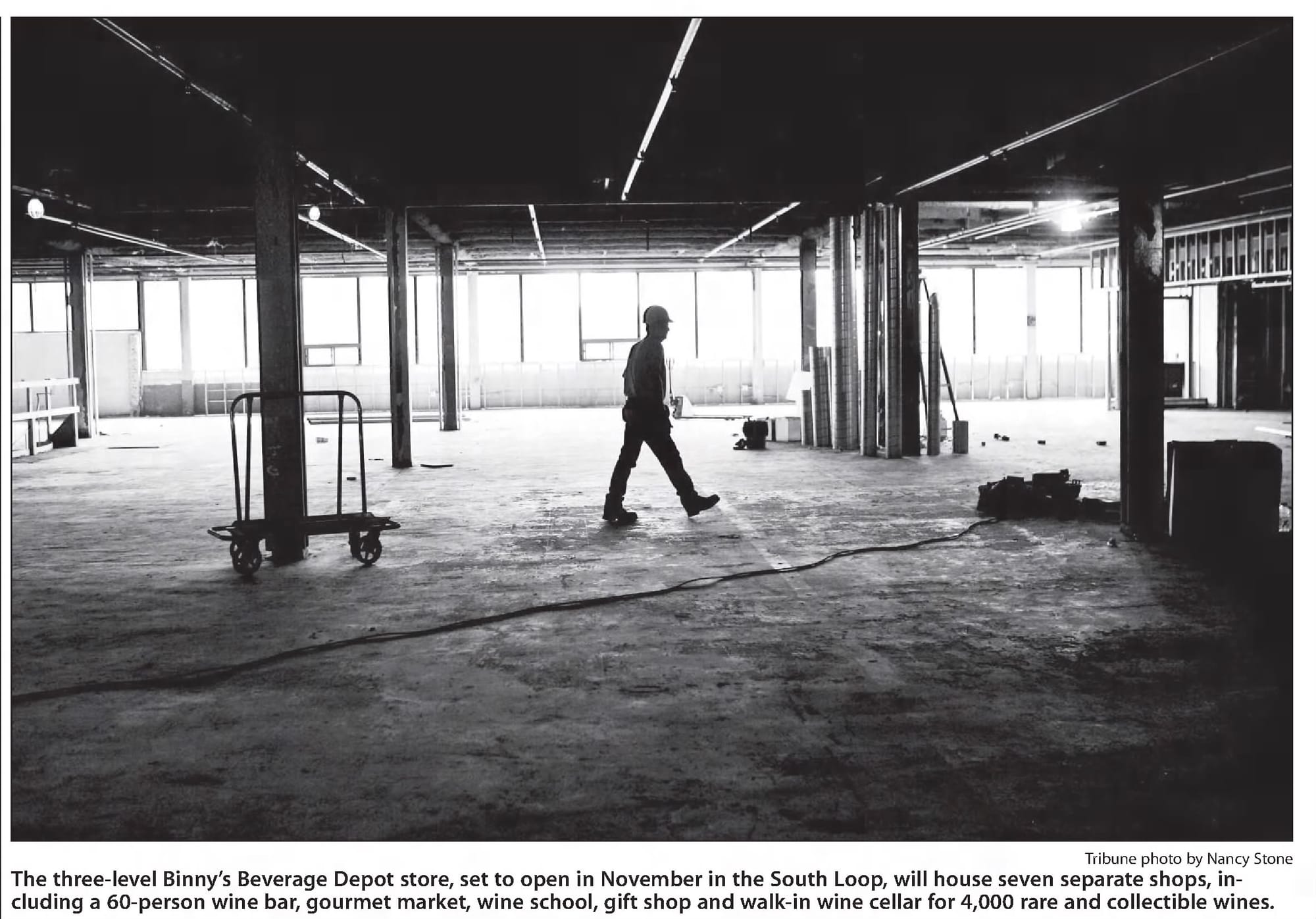

An Art Moderne factory turned liquor store feels like an especially Chicago version of adaptive reuse. Built in 1941 and designed by Frederick Stanton, the Kohl & Madden ink plant escaped the urban renewal that scoured this part of South Loop in the 1950s–presumably saved by its relative newness. Kohl & Madden plopped a floor on top in the mid-1960s, but the company–swallowed up by a Japanese conglomerate–left in the late 1970s, and the building housed a secretarial services and printing firm until Binny’s bought it in 2007. The local chain pushed the envelope converting the old ink factory into a massive liquor store, spending more than $12m to turn it into their then-largest location, envisioning a ‘Toys “R” Us for adults’.

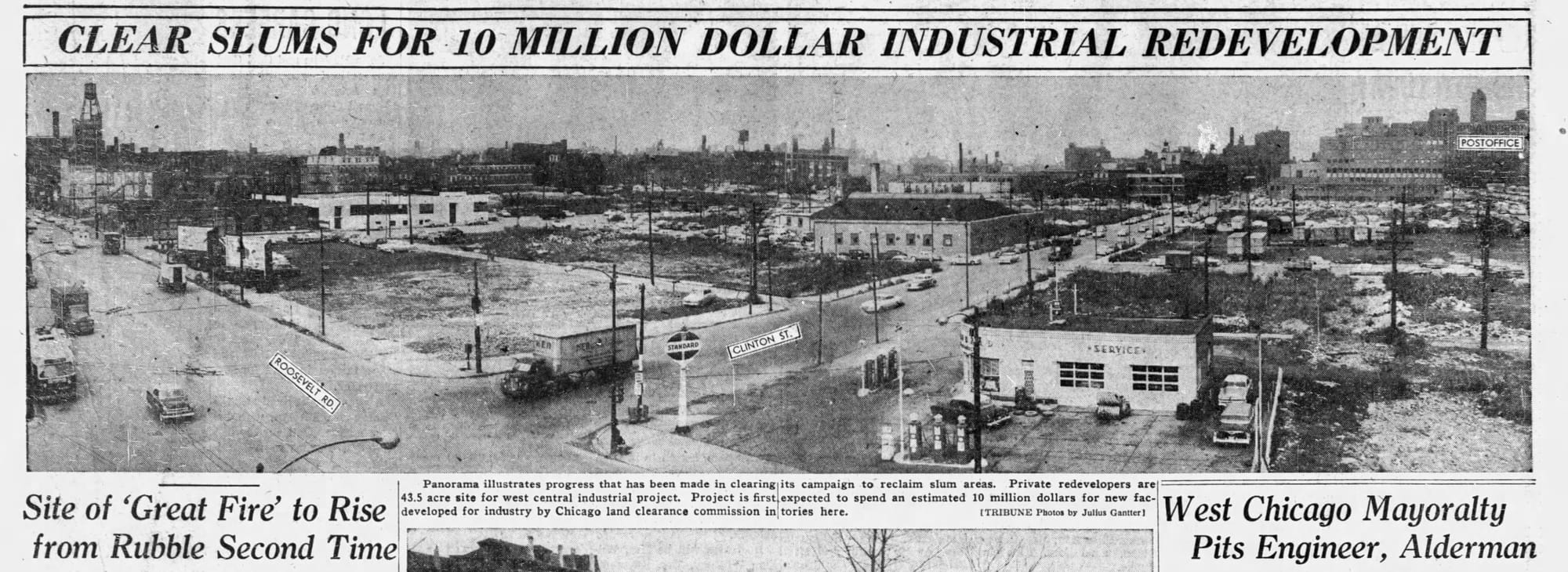

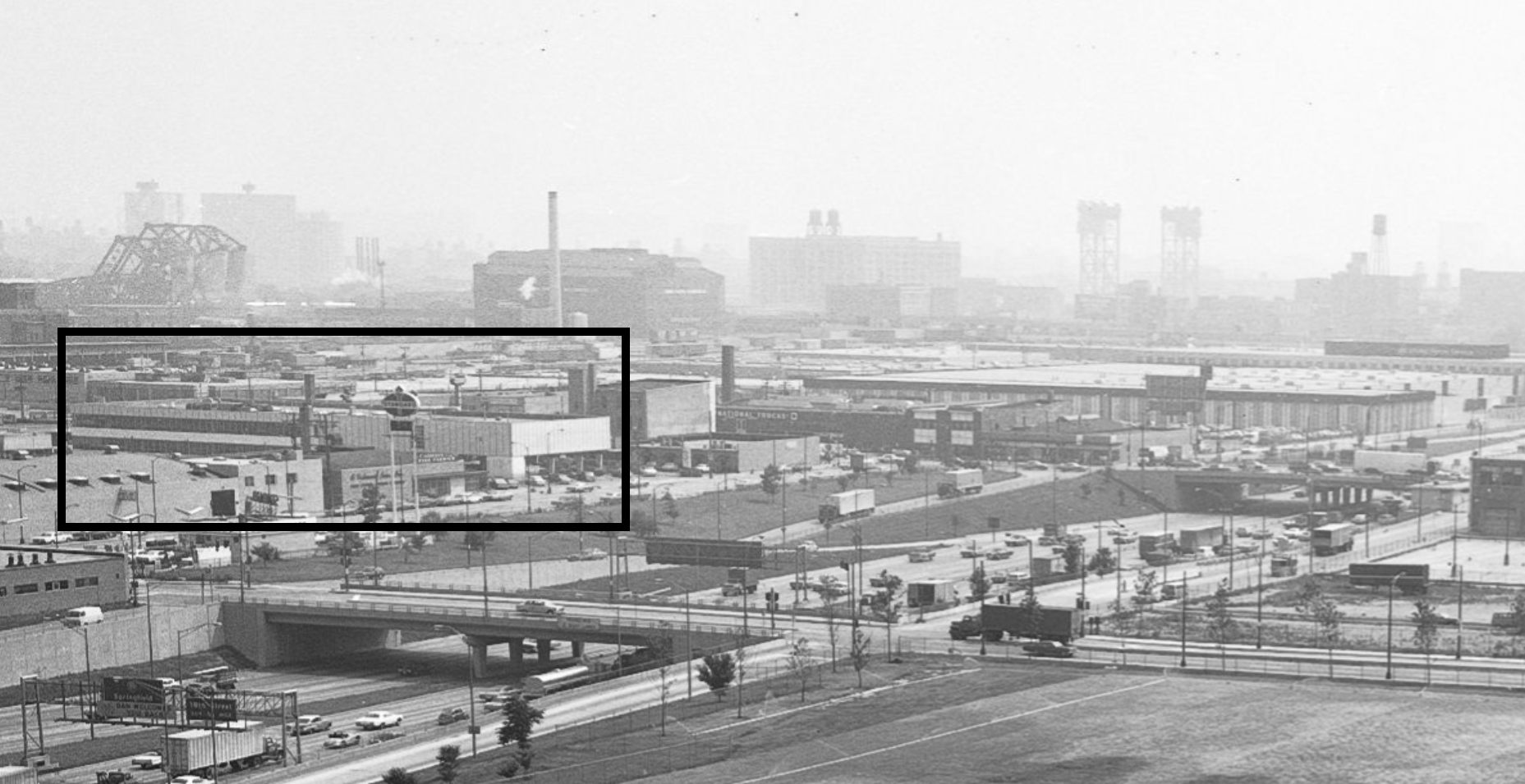

So what’s changed? This is an odd one, because the answer is sort of everything…but also nothing? The building itself is still identifiably there, but besides that monumental ribbed entryway and the placement of the windows, everything else is altered. The added floor is the biggest change, along with the disappearance of the neighboring buildings and the disappearance of Grenshaw Avenue–demolished during the “slum clearance” of the area, the right-of-way vacated, and everything eventually replaced with a covered parking structure for the factory. After buying the building, Binny’s painted it with their red and purple brand colors. Still, in a neighborhood that was mostly obliterated by urban renewal and that feels weirdly empty and suburban for an area 10 minutes from the Loop, I was pleasantly surprised to find this one hanging on.

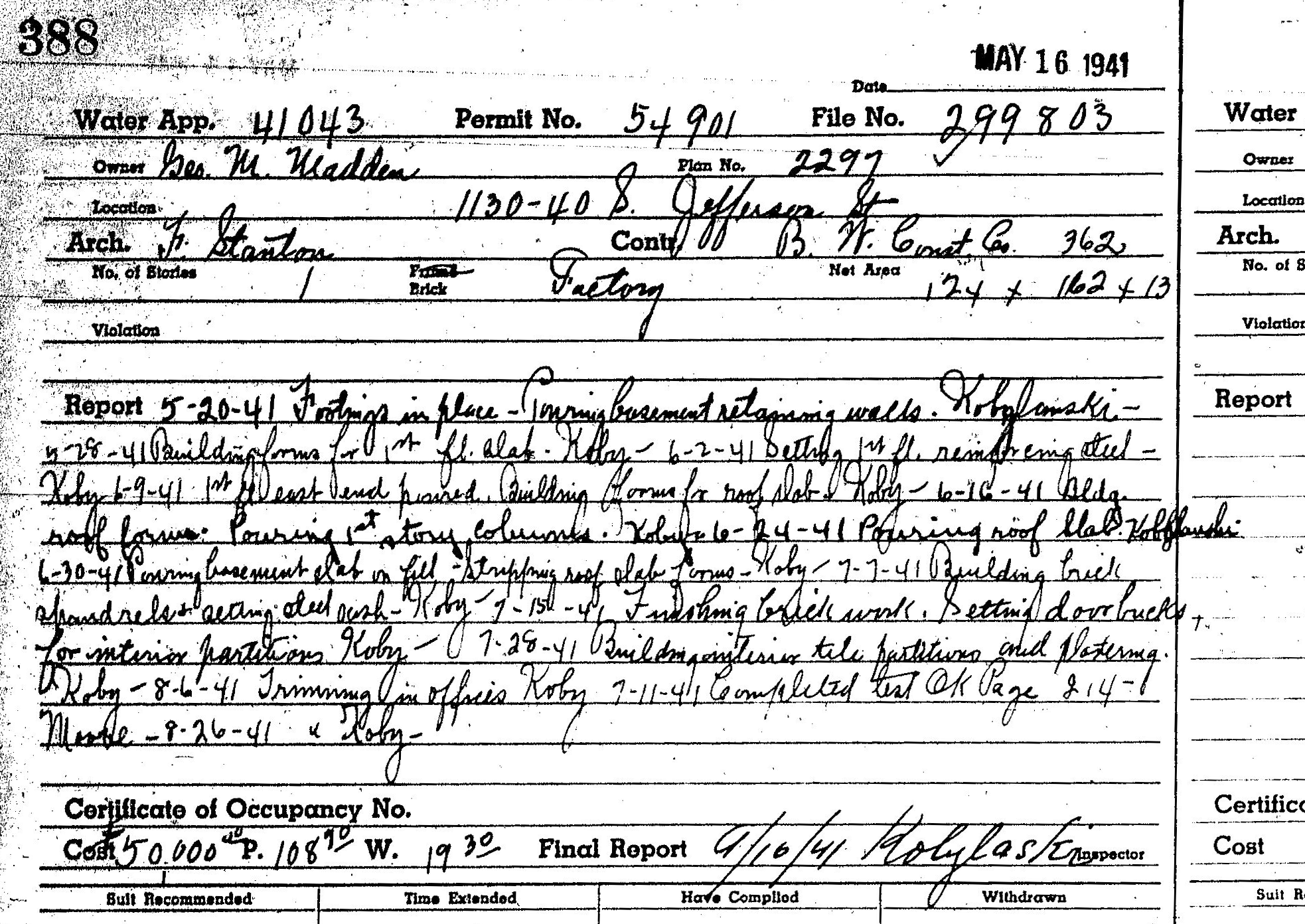

Kohl & Madden was an ink manufacturer, making letterpress, lithographic, offset, and gravure inks, as well as varnishes, compounds and driers. Before moving here, they were–appropriately–based in Printer’s Row, at 731 Plymouth Ct. Having survived the Great Depression and presumably outgrown their space in the Lakeside Press Building, the company hired Frederick Stanton to design them a new factory a mile southwest.

1915 ad, The Inland Printer, the Internet Archive | 1947 ad, Modern Lithography, the Internet Archive | 1948 ad, Modern Lithography, the Internet Archive | 1941 building permit, Chicago Building Permits Collection, UIC | 1950 Sanborn Map | 1964 aerial photo, UIC Library |

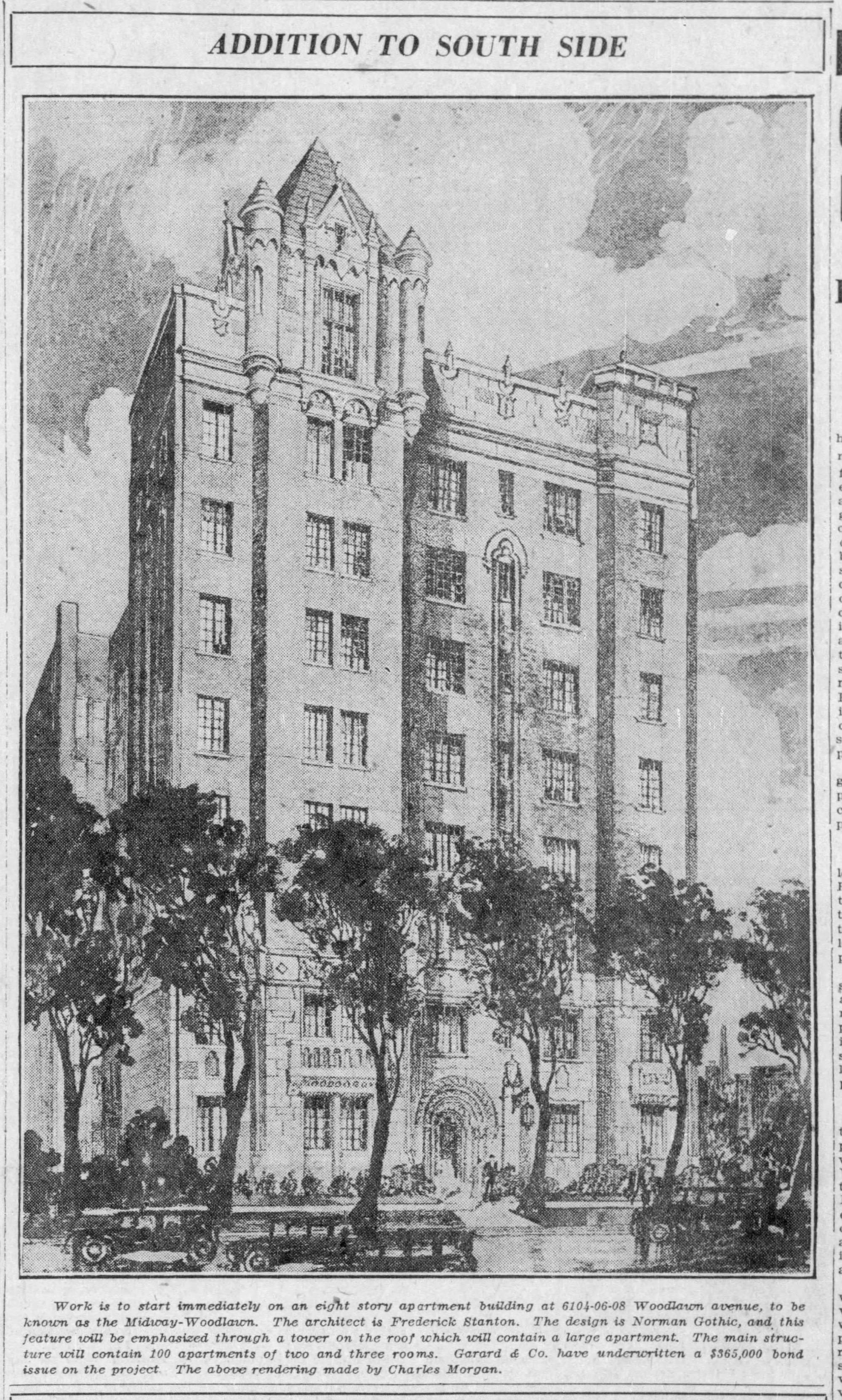

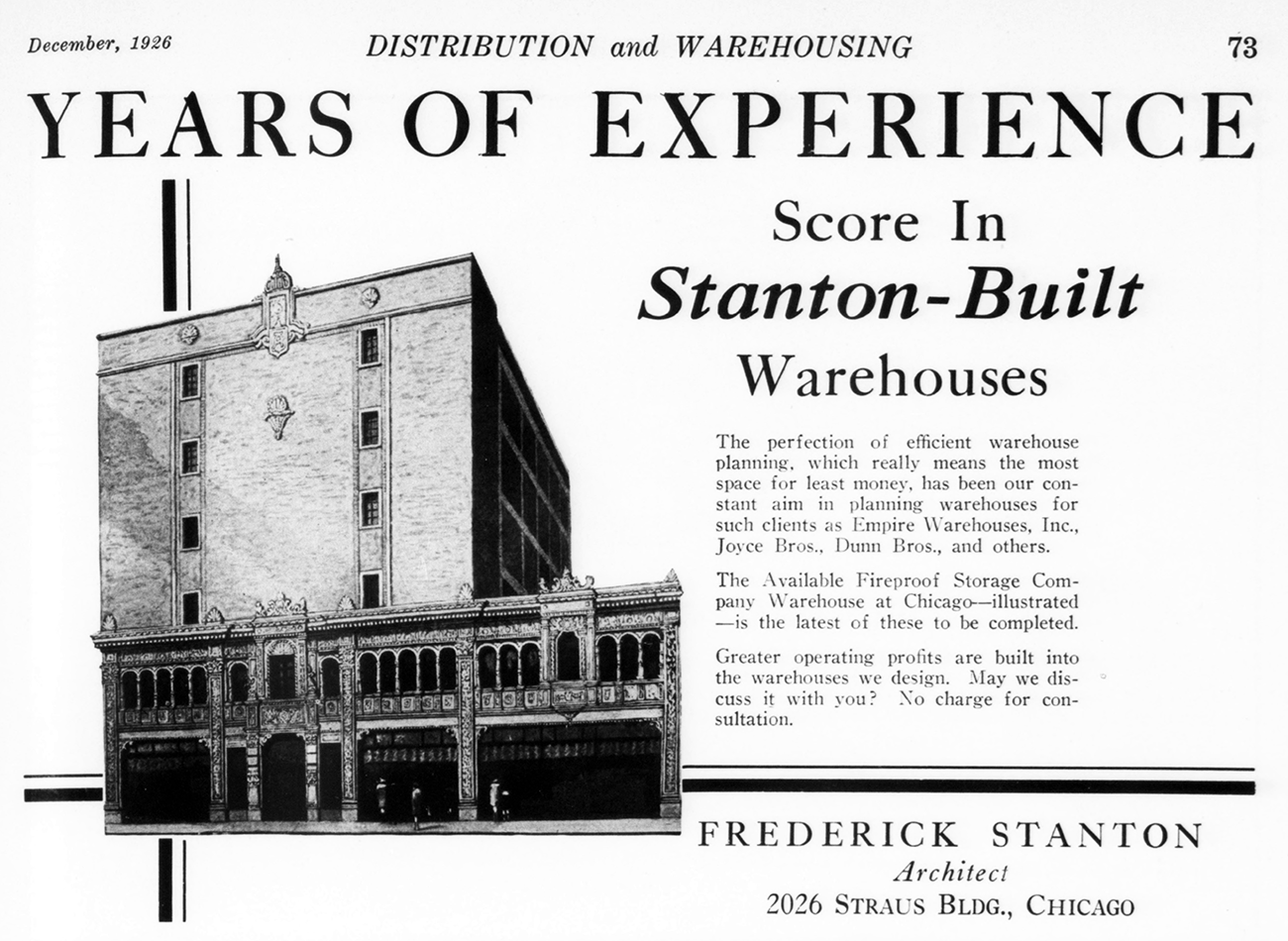

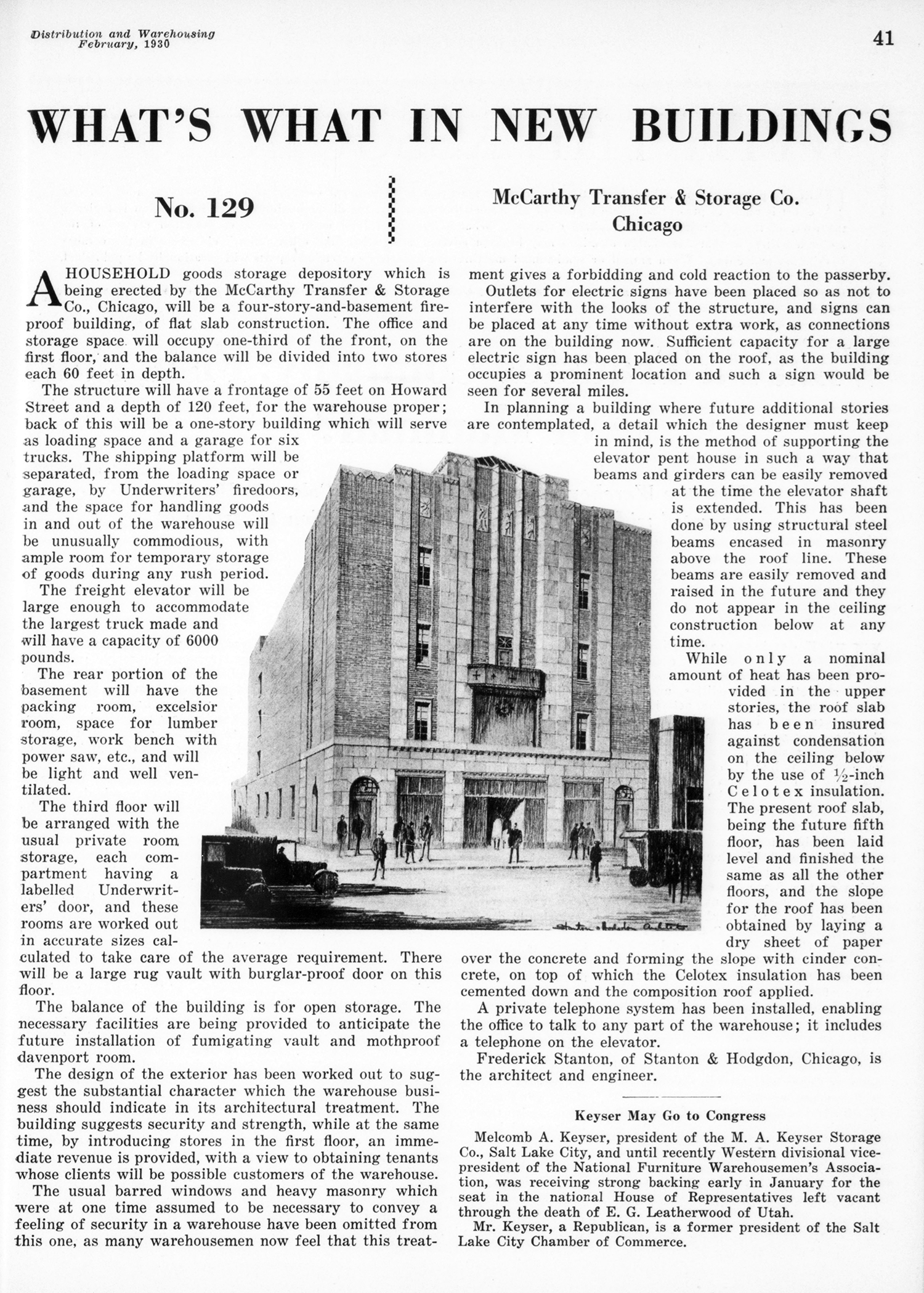

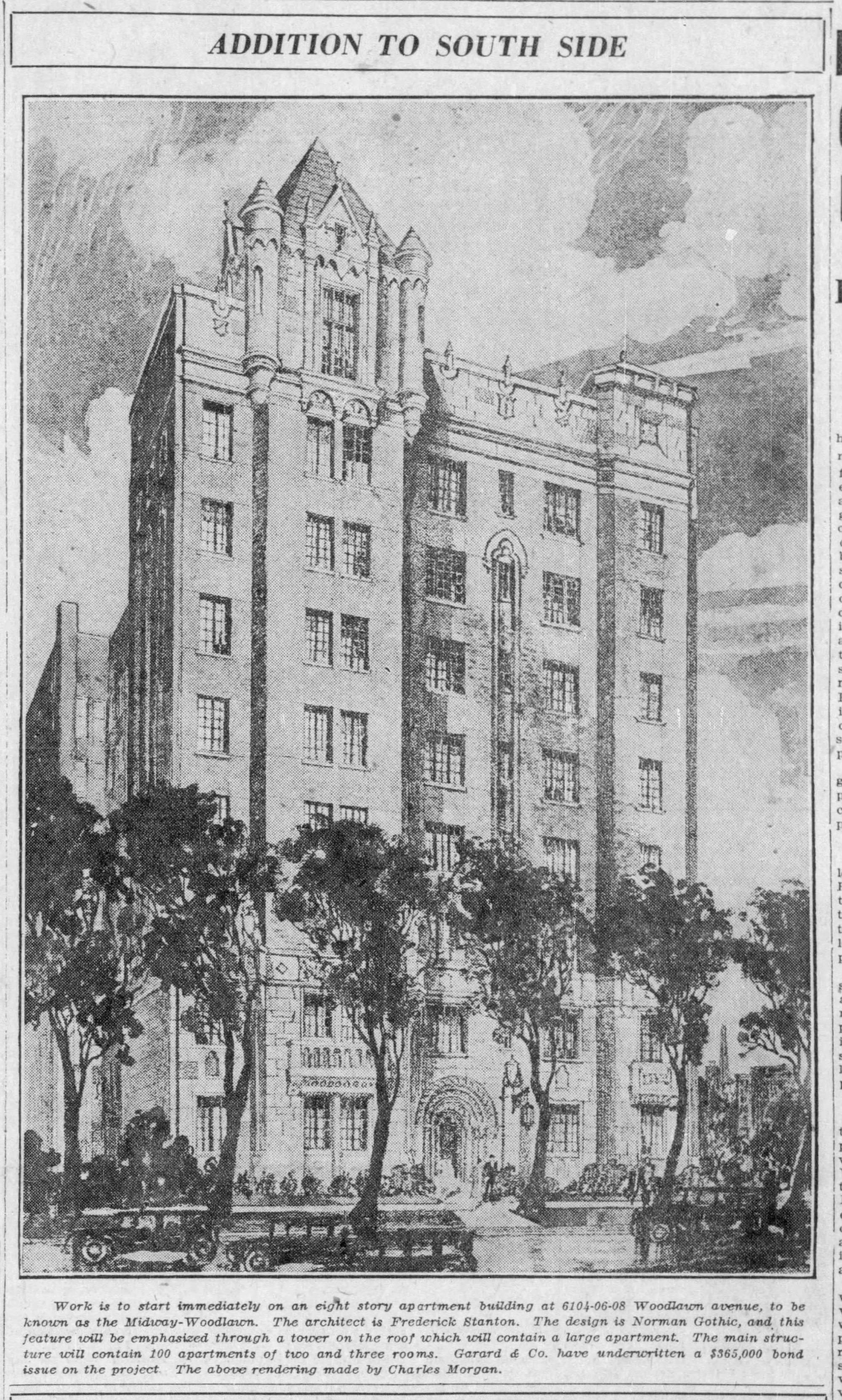

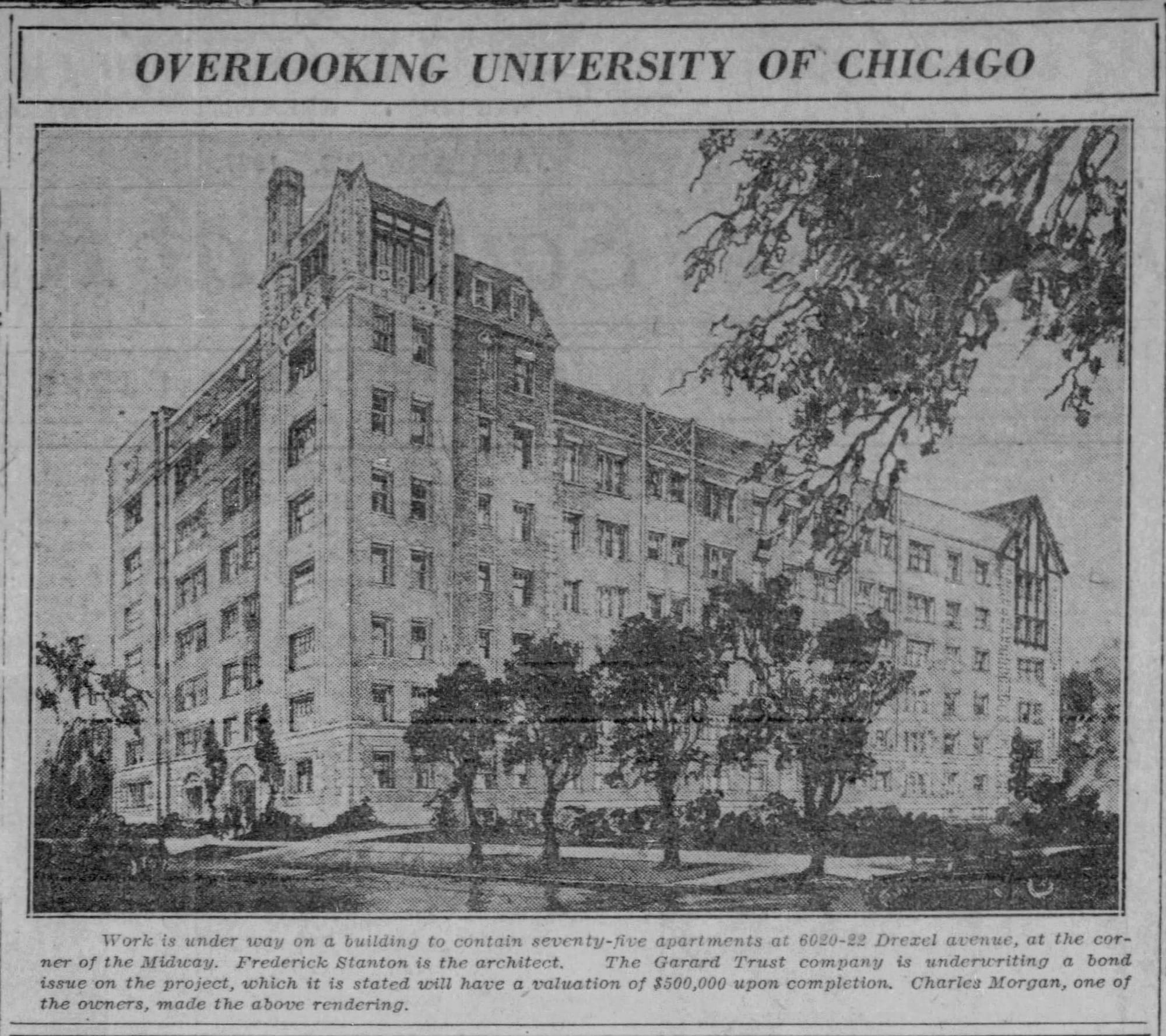

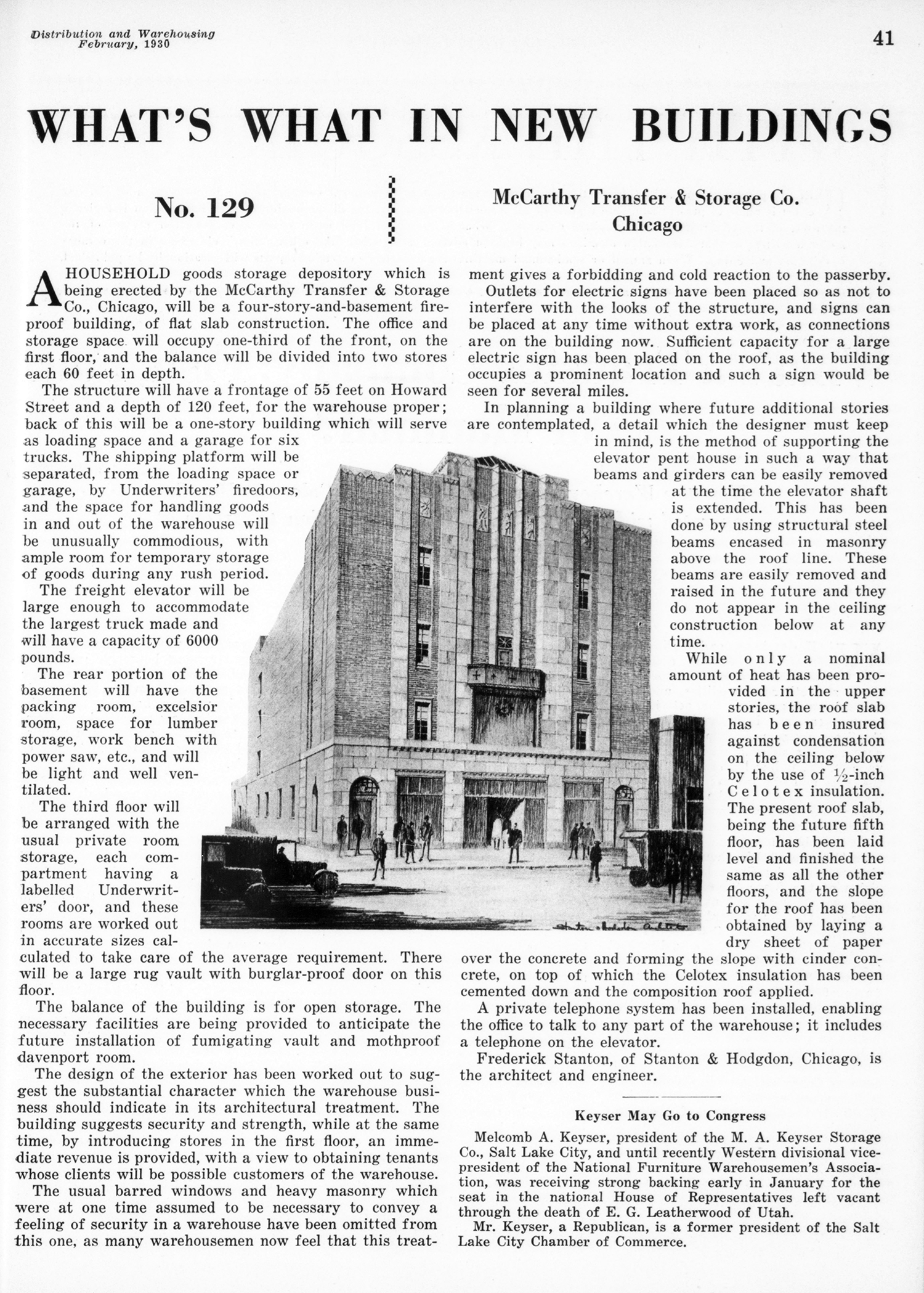

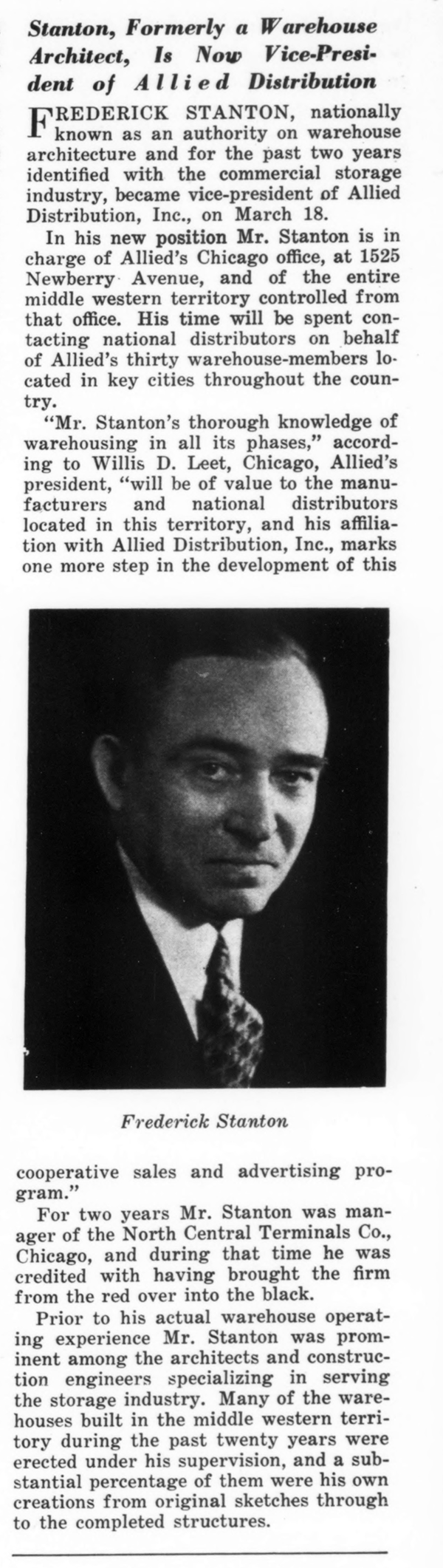

Obscure today, Stanton appears to have been pretty prolific from the late 1920s through the 1940s. A specialist in designing storage warehouses, he also did some neat mid-rise apartment buildings, churches, and at least one single family home. The first years of the Great Depression also mark a clear stylistic turning point in his practice, from various revival styles (Moorish, Gothic, Renaissance, Tudor, etc.) to a stripped down Art Deco and Art Moderne. Stanton’s buildings also often have an asymmetrical flourish, something you see here with the placement of the factory’s showy entrance. While his work is almost completely forgotten today, a bunch of Stanton-designed warehouses still stand around Chicago–George S. Kingsley is the city’s most famous storage architect, but it seems to me like Stanton’s firm belongs up there with him.

Buildings designed by Frederick Stanton: 1926, the Midway-Woodlawn Apartments | 1926, a fireproof storage warehouse on Stony Island in Distribution & Warehousing, the Internet Archive | 1928, Dr. John L. Conner Fellowship Hall, Eric Allix Rogers, Flickr | 1930, McCarthy Storage Co. on Howard, Distribution & Warehousing, the Internet Archive | the Royal York Apartments, Pittsburgh, Wikimedia Commons | 2024, 1132 S. Jefferson

Kohl & Madden refused the buyout offers during the area’s urban renewal in the 1950s, and in 1965-1966 they took advantage of their emptied surroundings to add another floor and a covered parking area. The ink company was acquired by Japan-based Dainippon Ink & Chemicals (DIC) in 1976, foreshadowing the wave of Japanese acquisitions that defined the 1980s. Kohl & Madden left this facility in the late 1970s or early 1980s. In 1987, DIC bought Sun Chemical and folded Kohl & Madden, which specialized in sheetfed inks by that point, into Sun Chemical. It looks like the brand was retired sometime in the 2000s.

Visible in a 1957 article about slum clearance | 1964 from across the Dan Ryan, pre-expansion, UIC Library | 1966 from across the Dan Ryan, after the second story was added along with the parking structure, UIC Library | undated photo of the interior of the ink plant, Paul Scot August | visible in the background from inside Manny's Deli, 2000, Yvette Dostatni, UIC via Chicago Collections | 2007 articles about Binny's buying the building and renovating it into their largest liquor store | 2007 ads for the grand opening

Anderson Printing and Anderson Secretarial operated out of the old ink factory in the 1980s and 1990s. After taking over the family distributor and liquor store chain from his father in 1995, Michel Binstein pushed for growth, expanding Binny’s in both number and size, adding large superstores. When they bought the building in 2007, Binny’s set about turning it into their largest location yet. Spending $6.7m to buy the old ink plant, the company spent another $5.5m renovating it for retail. In a real time capsule, Chicago Cubs manager Lou Piniella threw out a first pitch to inaugurate the new South Loop Binny’s superstore in December 2007 (Lorraine Bracco, Mike Ditka, and Tommy Lasorda also were hired for various grand opening festivities). It’s no longer their biggest–the company’s Lincoln Park location took that title in the 2010s–but almost 20 years later it remains a Binny’s, and a somewhat quirky but clearly successful example of adaptive reuse.

2024

Production Files

For someone almost completely forgotten, there are a bunch of Frederick Stanton buildings still standing around Chicago. In the 1920s, his firm had two specialties: fireproof storage warehouses and mid-rise apartment buildings (which are basically just storage warehouses for people, right [and hopefully similarly fireproof]). They often had some kind of asymmetrical turret or penthouse.

The Midway-Woodlawn (now the Plaisance Apartments) at 6104 S Woodlawn, 1926 | 6022 S Drexel, now a University of Chicago dorm, 1926 | 88 Robsart Blvd., a single-family home Stanton designed in Kenilworth, ad in Architectural Forum, 1926, the Internet Archive

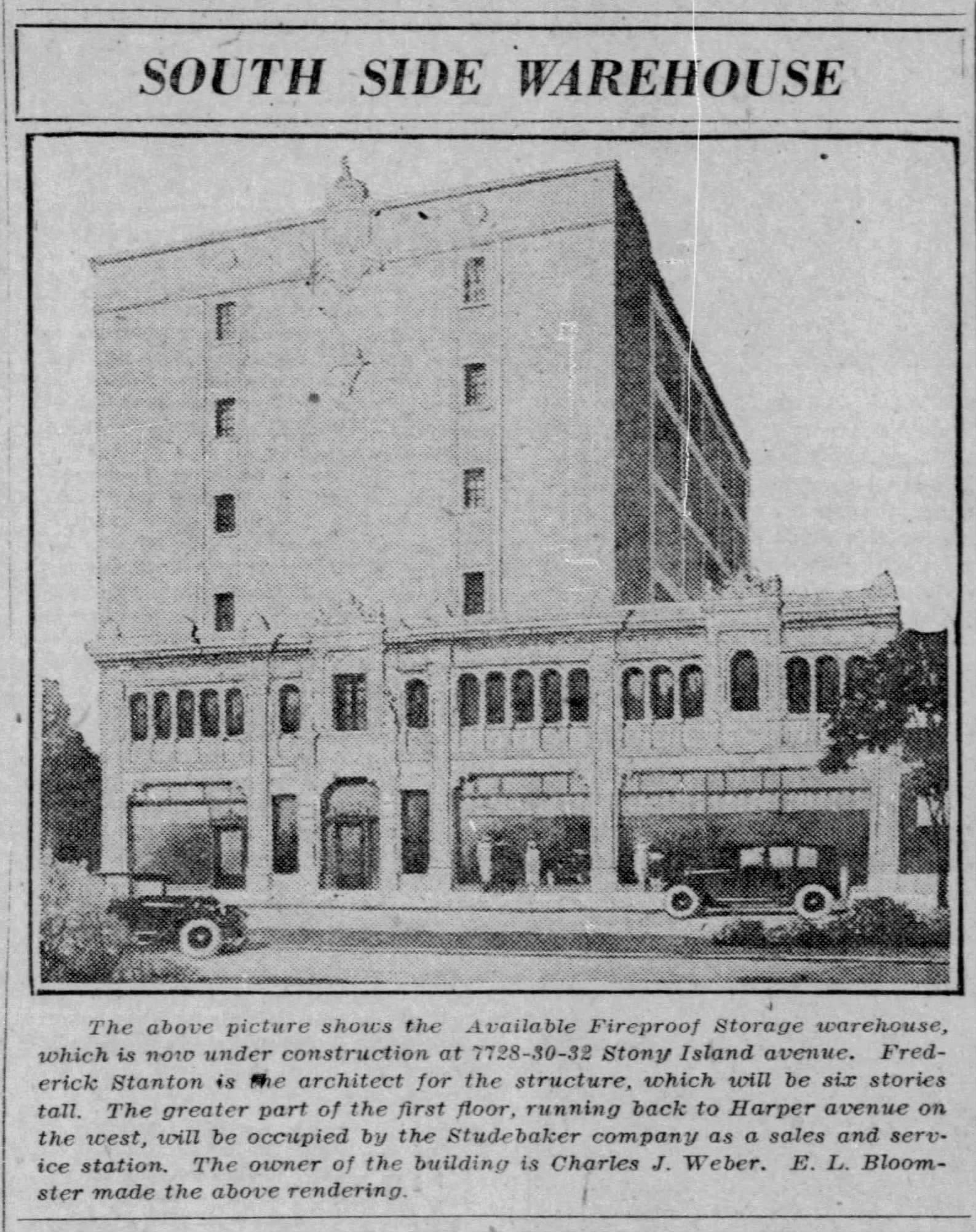

The storage warehouses often also had some kind of auto sales and service center attached.

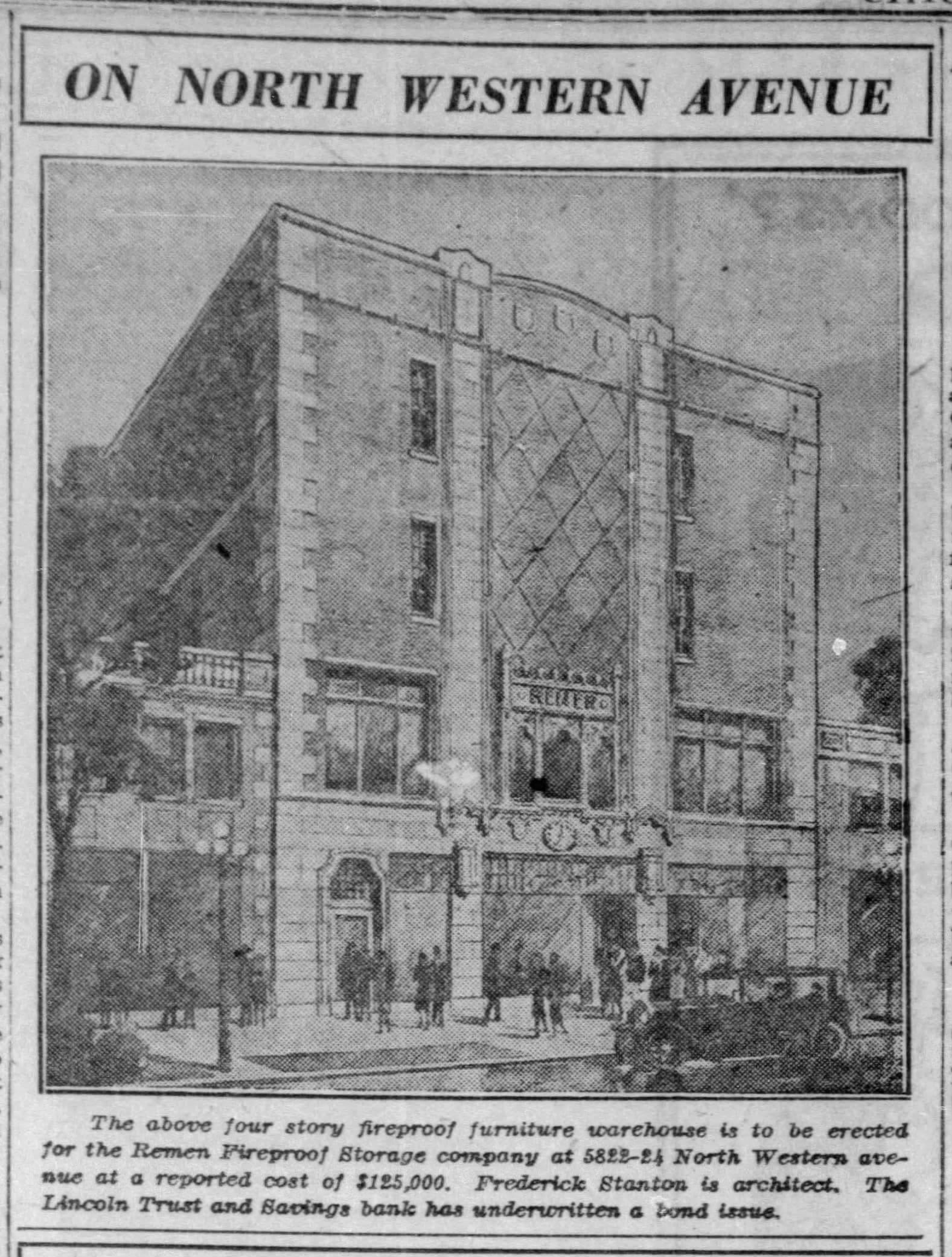

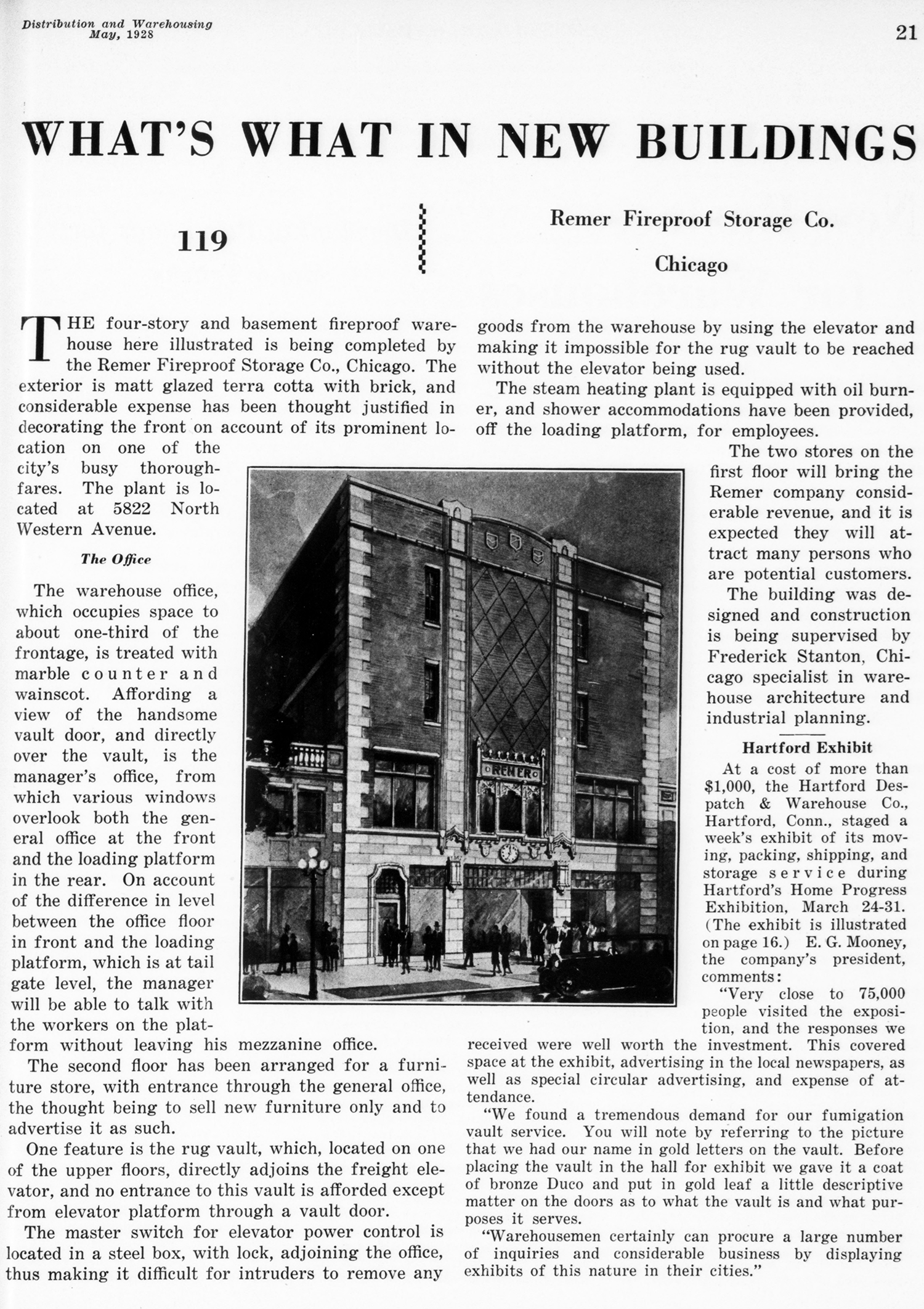

Joyce Bros. Storage, 7415 S. Stony Island, 1927, in Distribution & Warehousing, the Internet Archive and present day aerial photo | Leonard Detroit Storage, 10911 Grand River Ave in Detroit, 1927, in Distribution & Warehousing, the Internet Archive and 2023 Google Streetview | 1927 Tribune article on auto showroom and warehouse at 7150 S. Stony Island and 2019 Google Streetview | Remer Fireproof Storage Warehouse at 5822 N. Western, 1928 Chicago Tribune article, in Distribution & Warehousing, and 2022 Google Streetview

The wild Moorish Revival John L. Connor Fellowship Hall at 7900 S Chicago Ave is one of only two buildings attributed to Stanton in the Chicago Historic Resources Survey. He also designed at least a couple ecclesiastical buildings, including the Hope Reformed Church at 78th and Wolcott in Englewood, now the True Believers Missionary Baptist Church.

1928 article and 2018 streetview

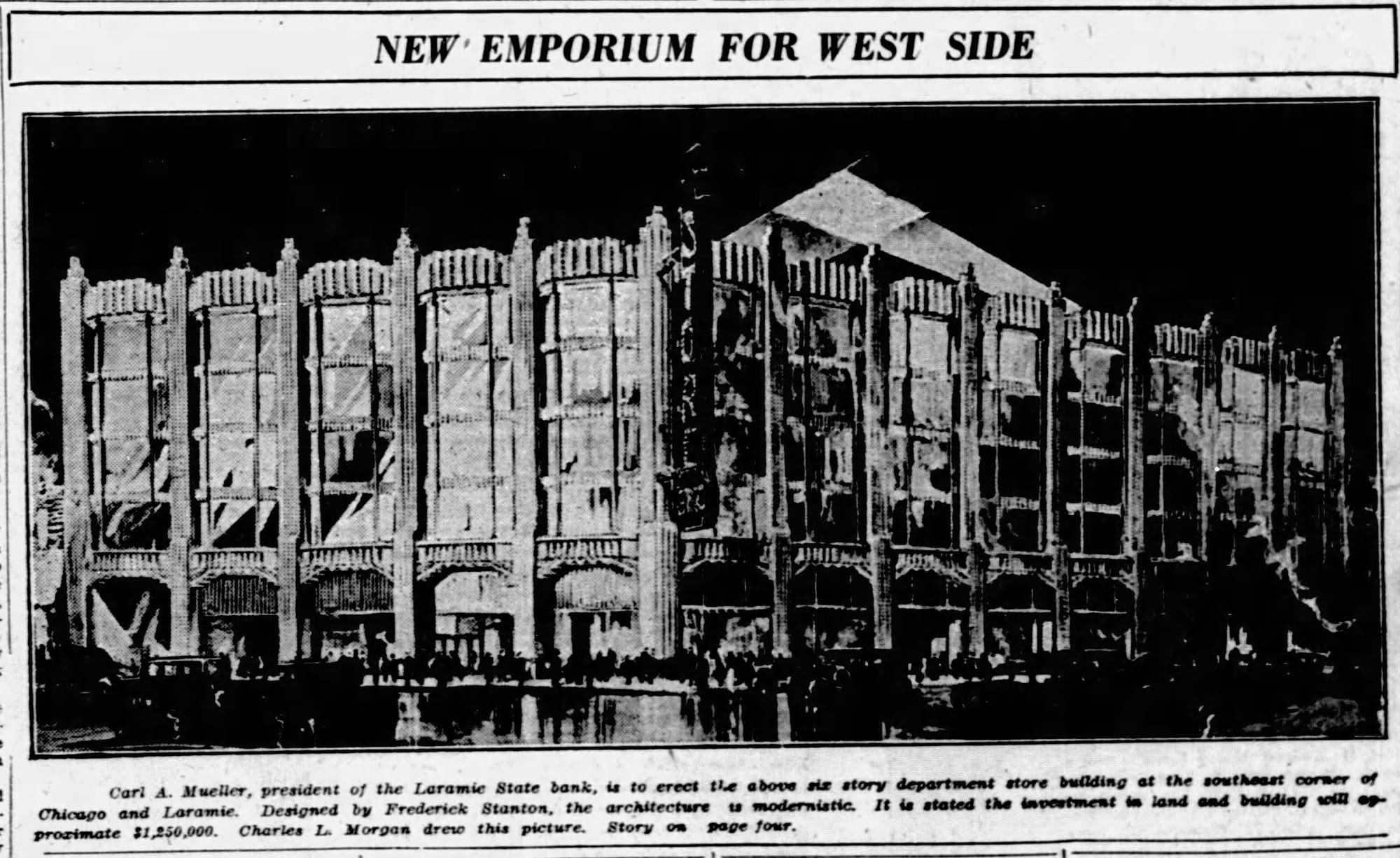

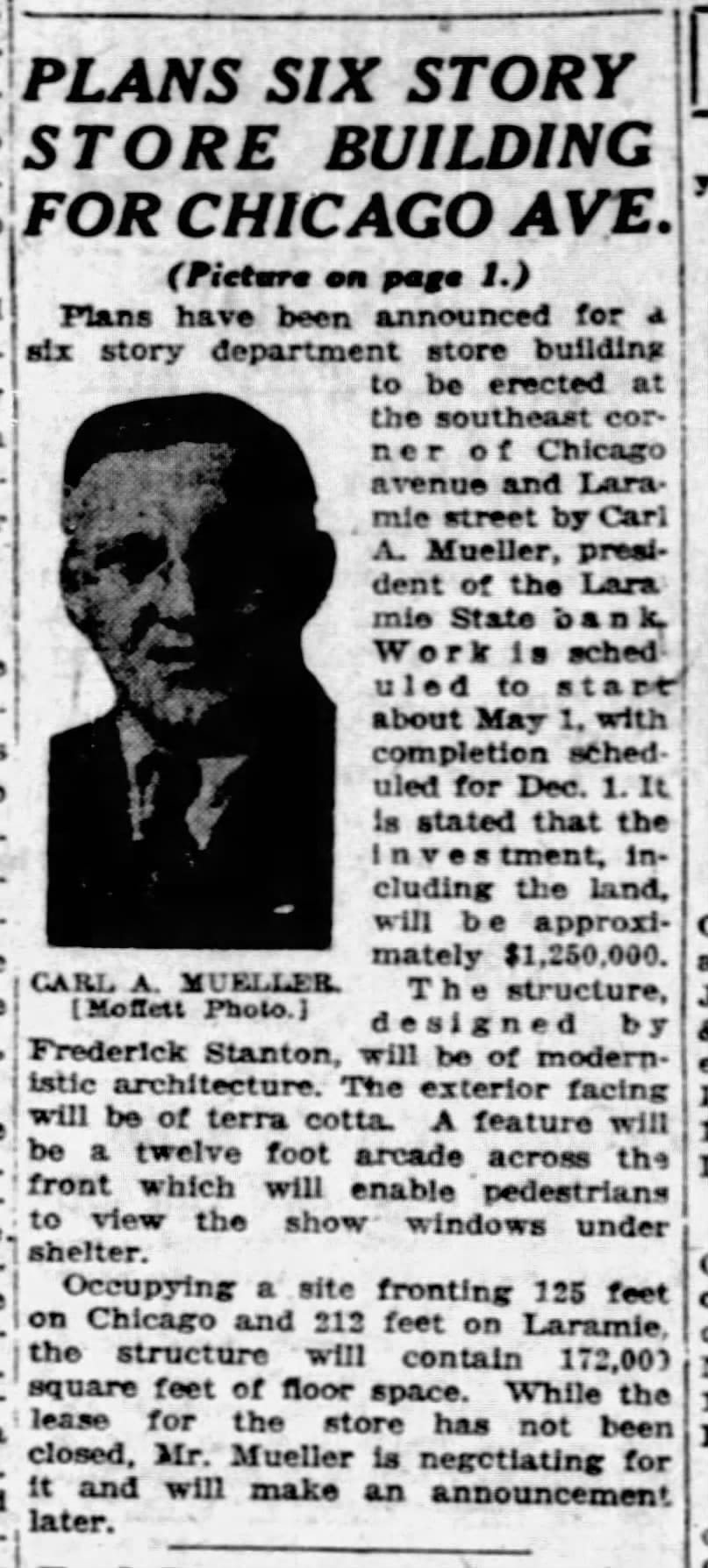

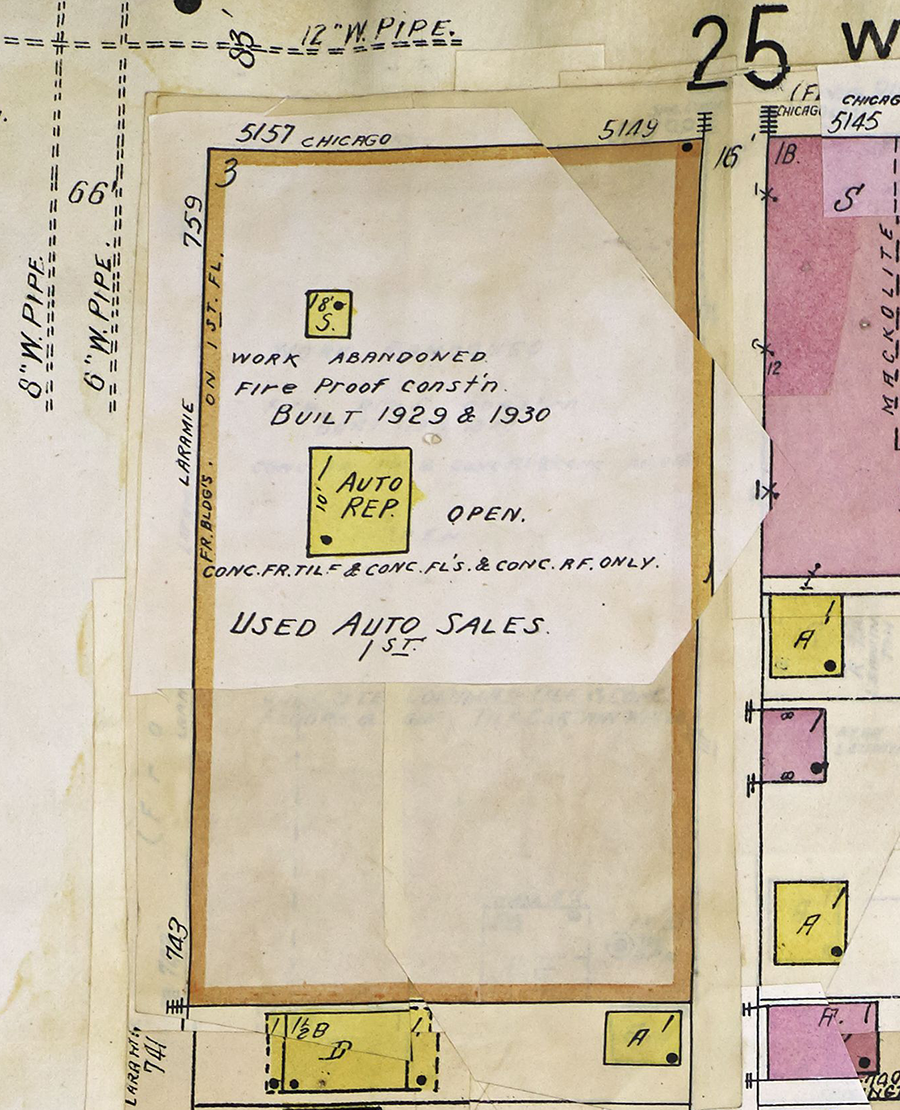

Stanton was hired to design a department store in Austin across from the Laramie State Bank building, but the Great Depression killed that project–even 20 years later in the 1950 Sanborn map the site is still listed as "work abandoned".

1929 article about the plans for a department store at Chicago Ave. and Laramie | 1950 Sanborn map with the site

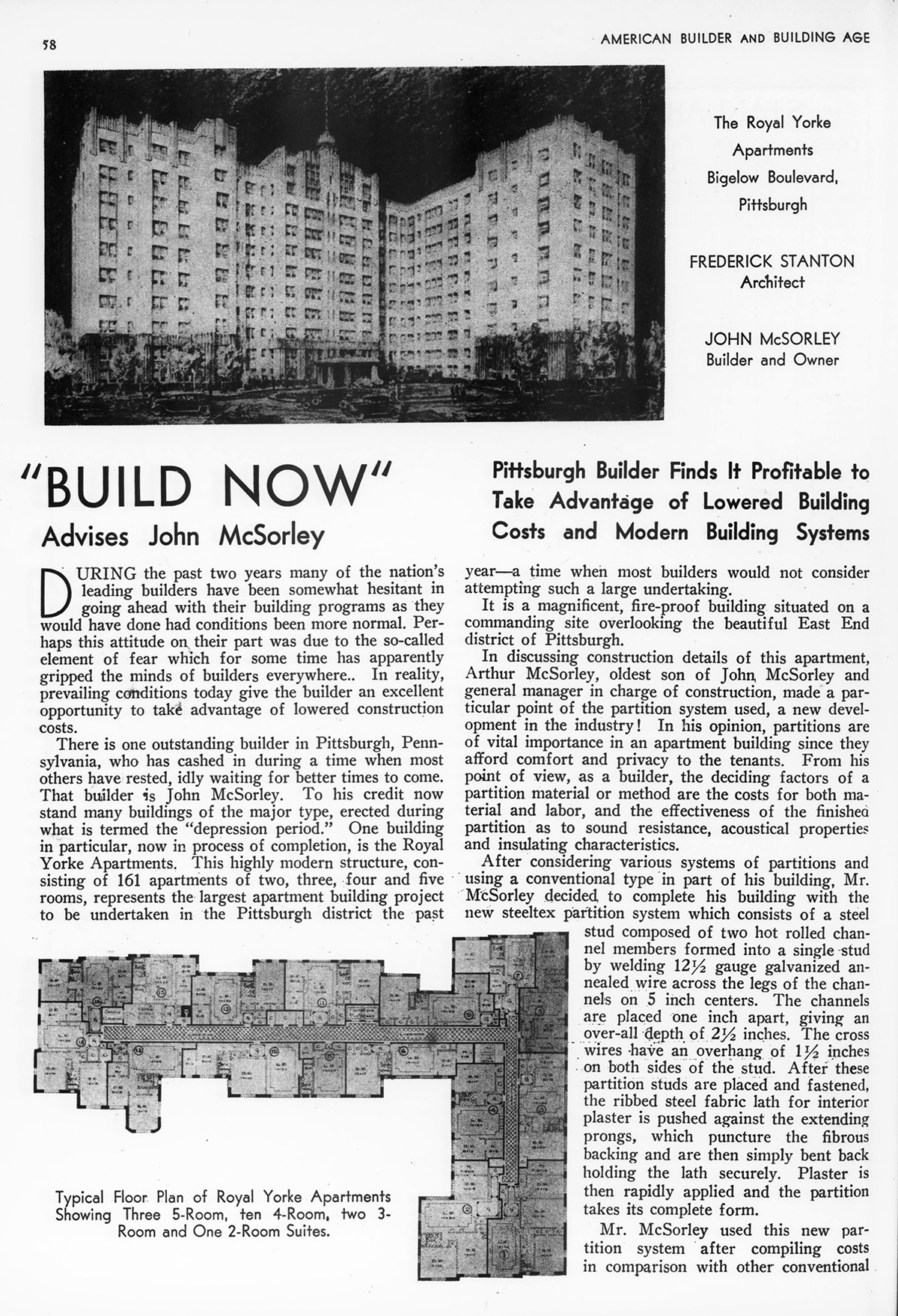

By the 1930s you can start to sense Stanton's style evolve away from revival styles and into Art Deco, most visible with the McCarthy Storage Warehouse in Rogers Park and the Royal York Apartments in Pittsburgh–but working in the building industry was terrible during the Great Depression, and in 1935 he wound up his firm and went in-house at a storage company.

1930, 2219 W. Howard in Distribution & Warehousing and 2009 Streetview

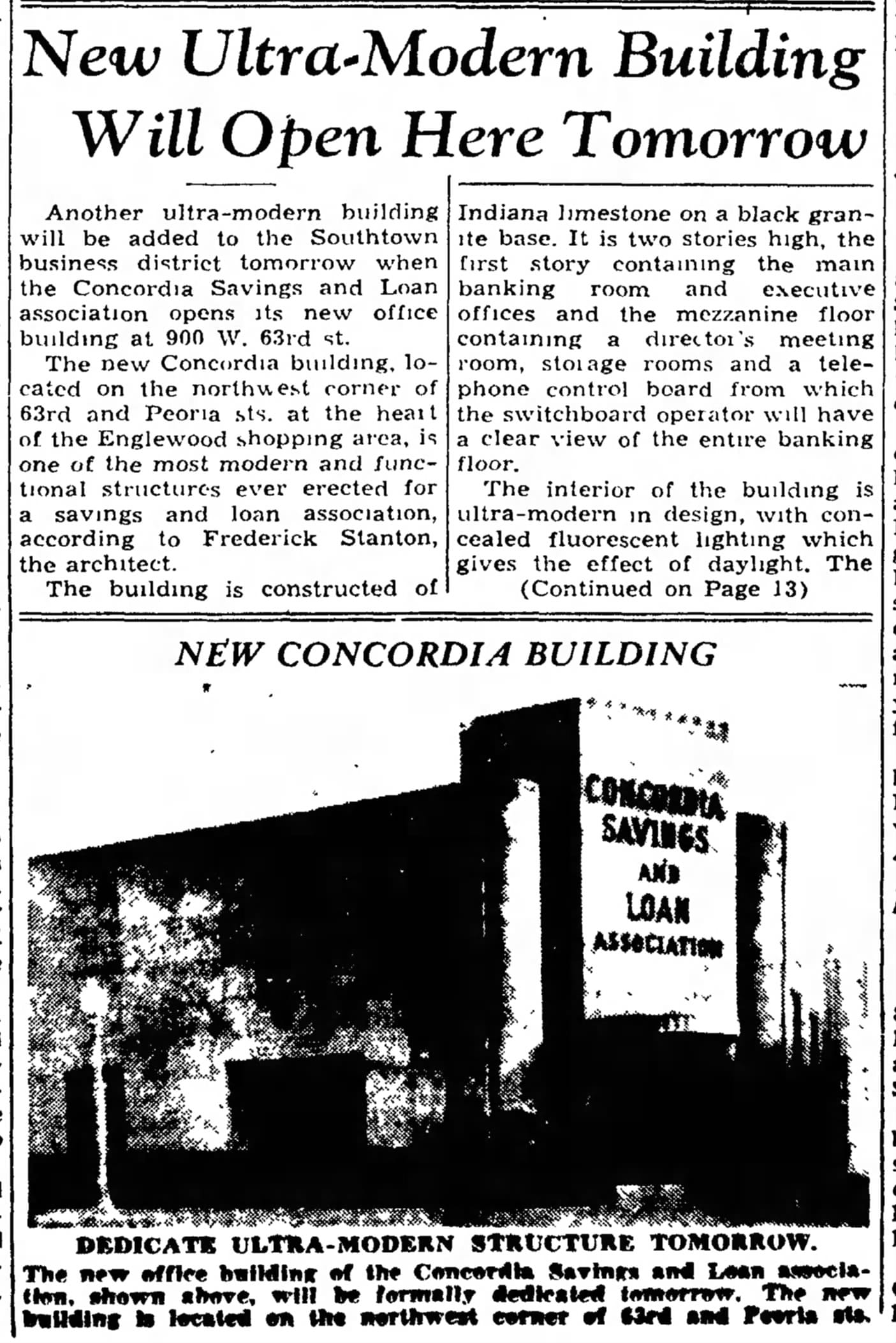

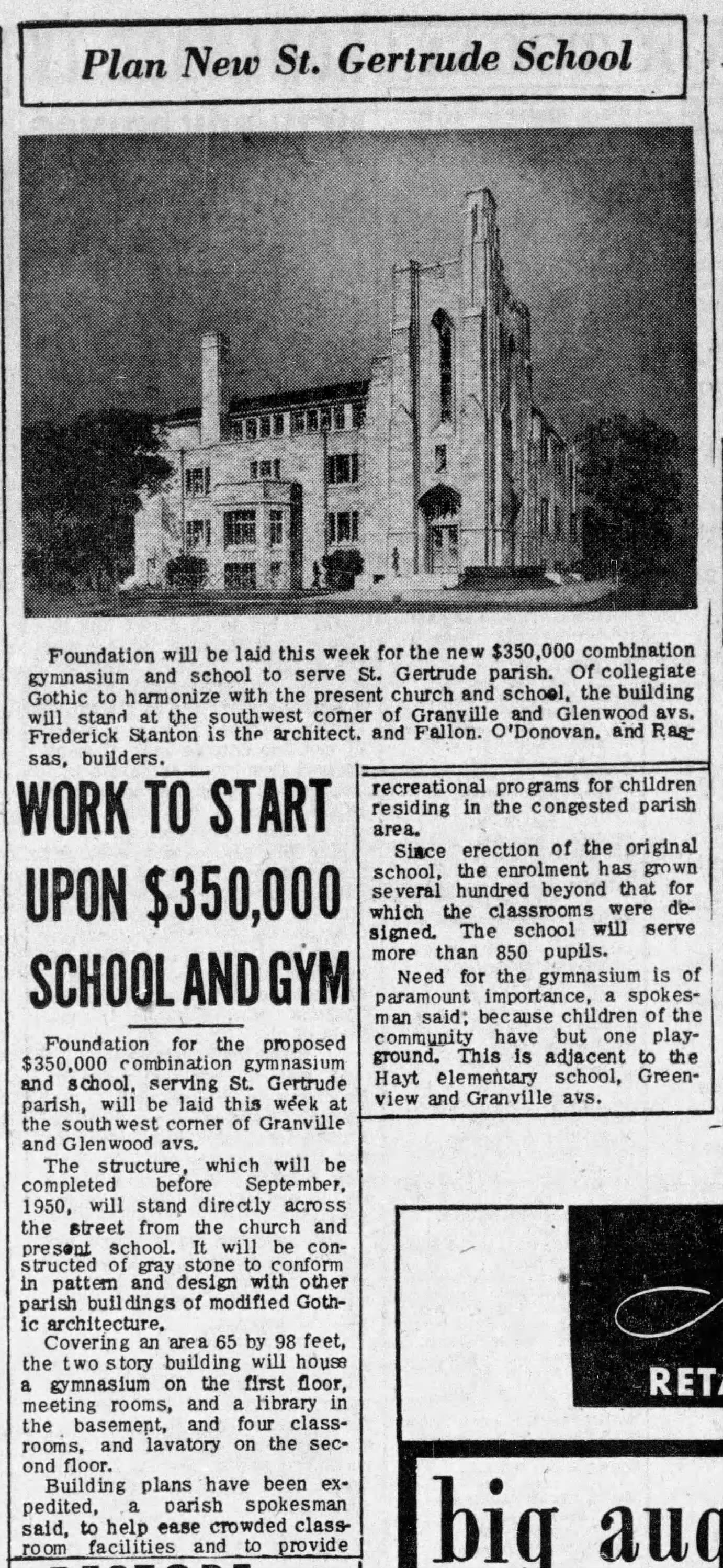

The Royal York Apartments in Pittsburgh, American Builder, 1932, the Internet Archive | the Royal York Apartments, Wikimedia Commons | 1935, "Stanton, Formerly a Warehouse Architect, Is Now Vice-President of Allied Distribution" in Distribution & Warehousing, 1935, the Internet Archive | 1935, Stanton designs Dave Fireproof Storage at 3240 W. Lawrence | 1941, Stanton designs a Moderne-looking bank in Englewood | Article about Stanton designing St. Gertrude School, 1401 W. Granville, and 2019 streetview

While there are many more Stanton-designed buildings scattered around Chicago than I expected, they didn't all make it–especially curious about the beer garden (supposedly Chicago's first after prohibition) at Clark and Thome.

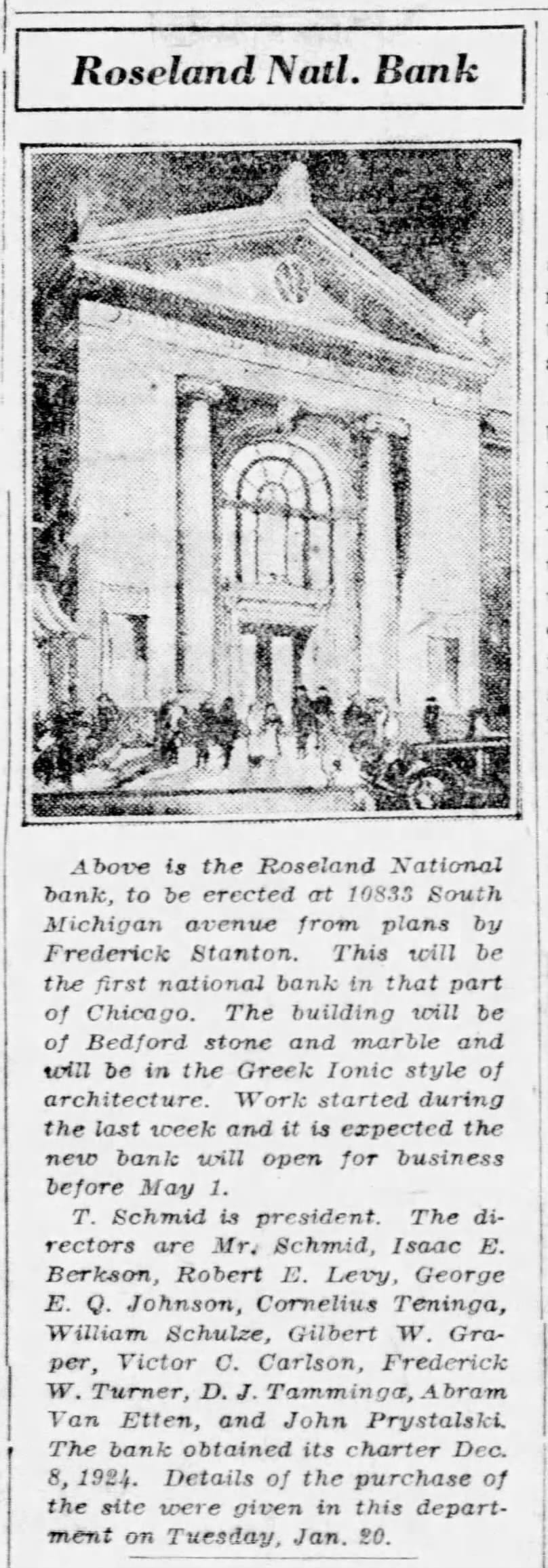

1925 article on a bank in Roseland, demolished | 1926 article on a storage warehouse at 7728 Stony Island, demolished | 1933 article on a Stanton-designed beer garden in Edgewater, demolished | 1939, a renovation to a Rogers Park department store, demolished

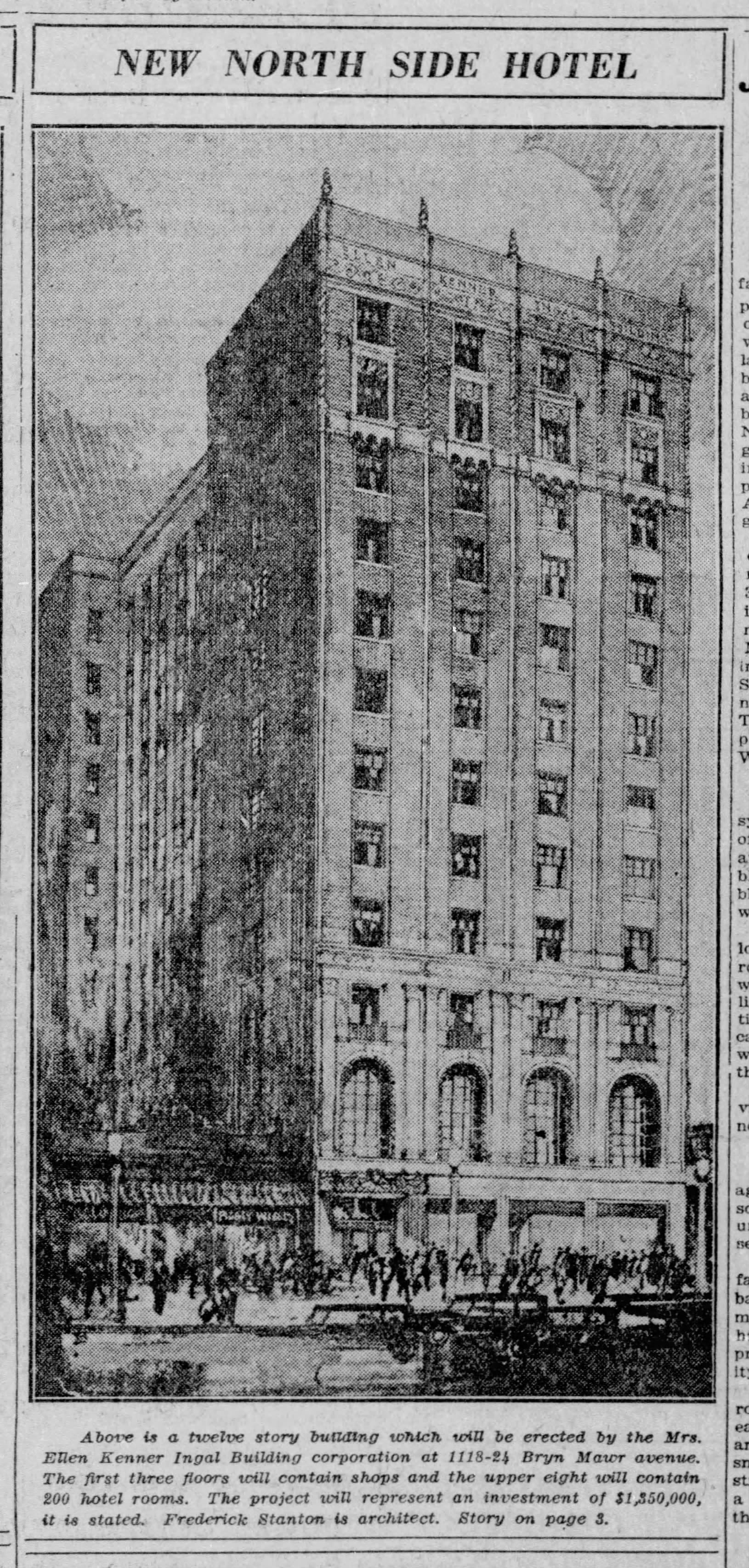

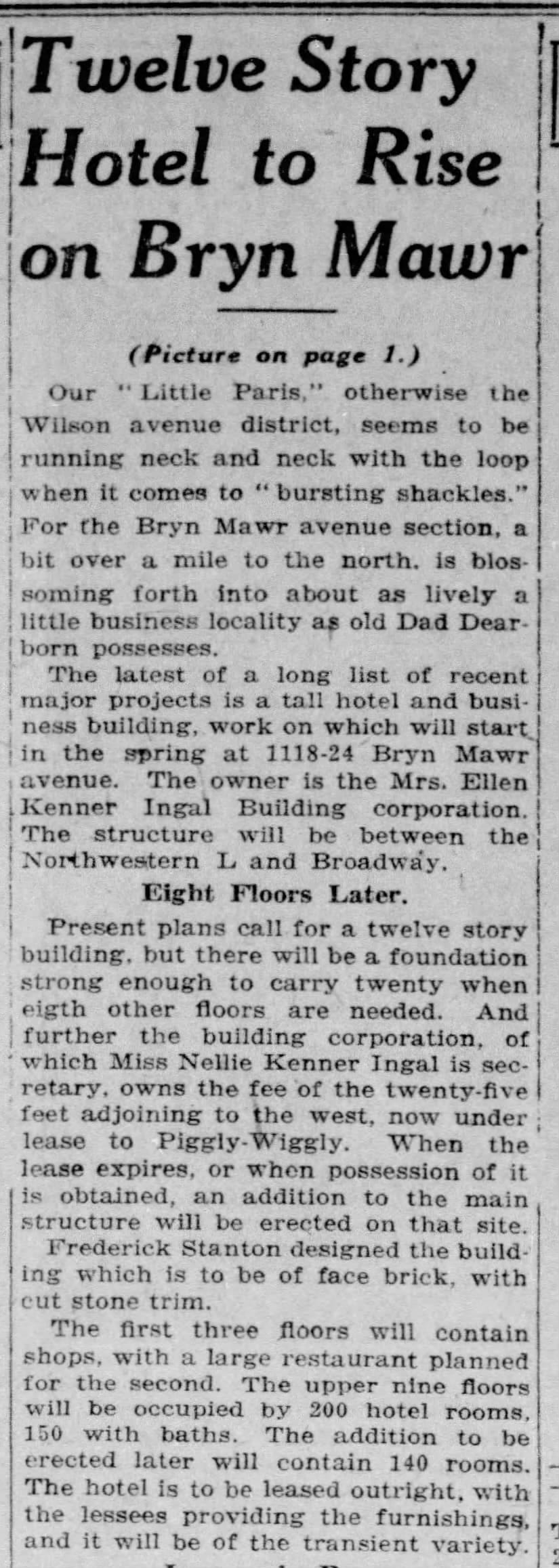

This was also kind of funny: even in the 1920s boom, not everything penciled out. This hotel on Bryn Mawr was never built and remains a single story taxpayer to this day–but the building still sports the name of the woman who hired Stanton to design this never-built mid-rise.

1926 articles about the hotel on W. Bryn Mawr.

Help wanted ads for Kohl & Madden: 1946, 1962, and 1963 | Help wanted ads for Anderson Printing: 1996 and 1999

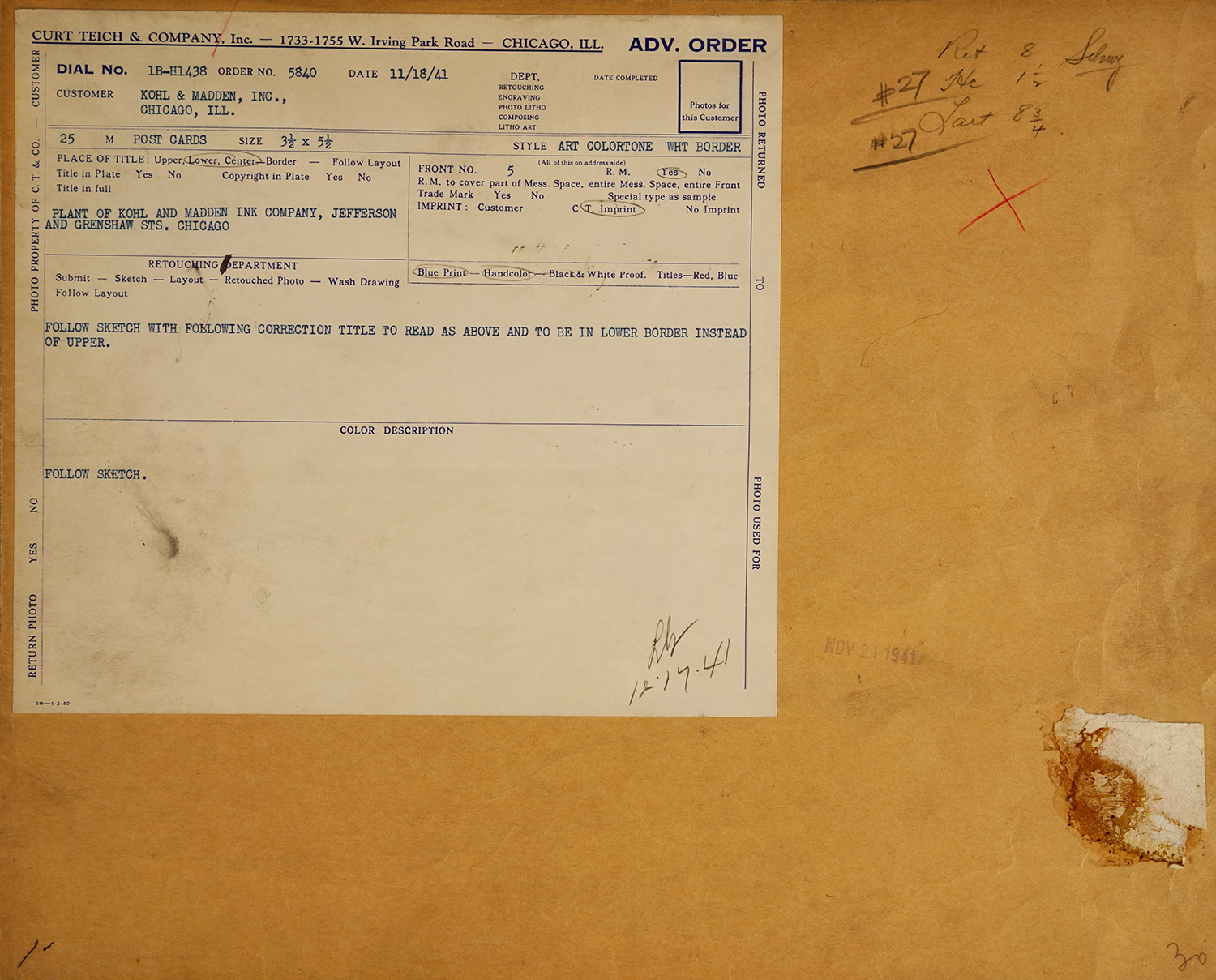

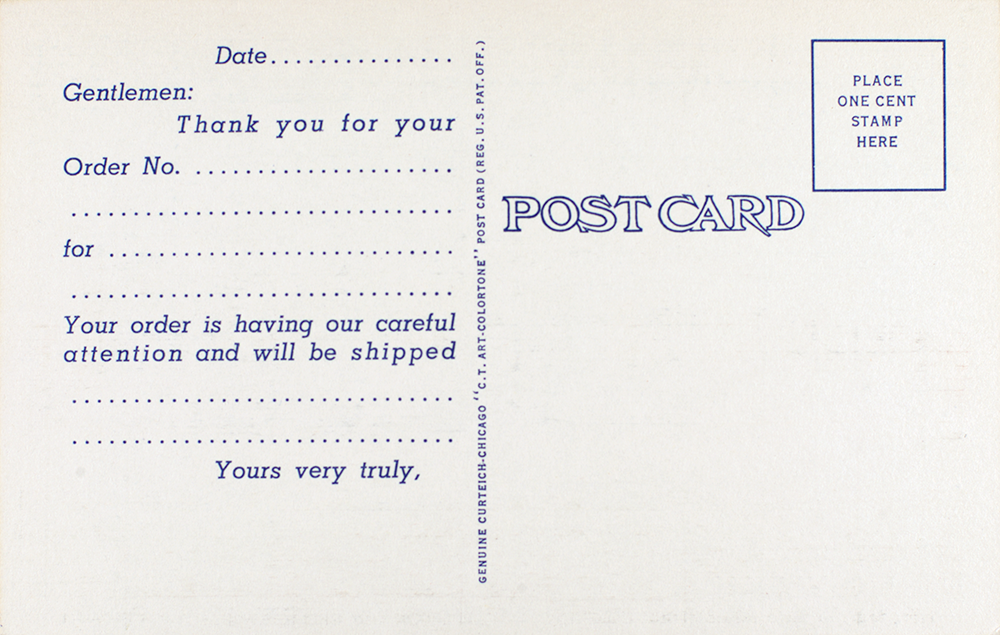

The Curt Teich production file envelope for the postcard, Newberry Library via the Internet Archive | postcard verso, Newberry Library via the Internet Archive

I've started to take photos of the location I take the present-day photos from.

Member discussion: