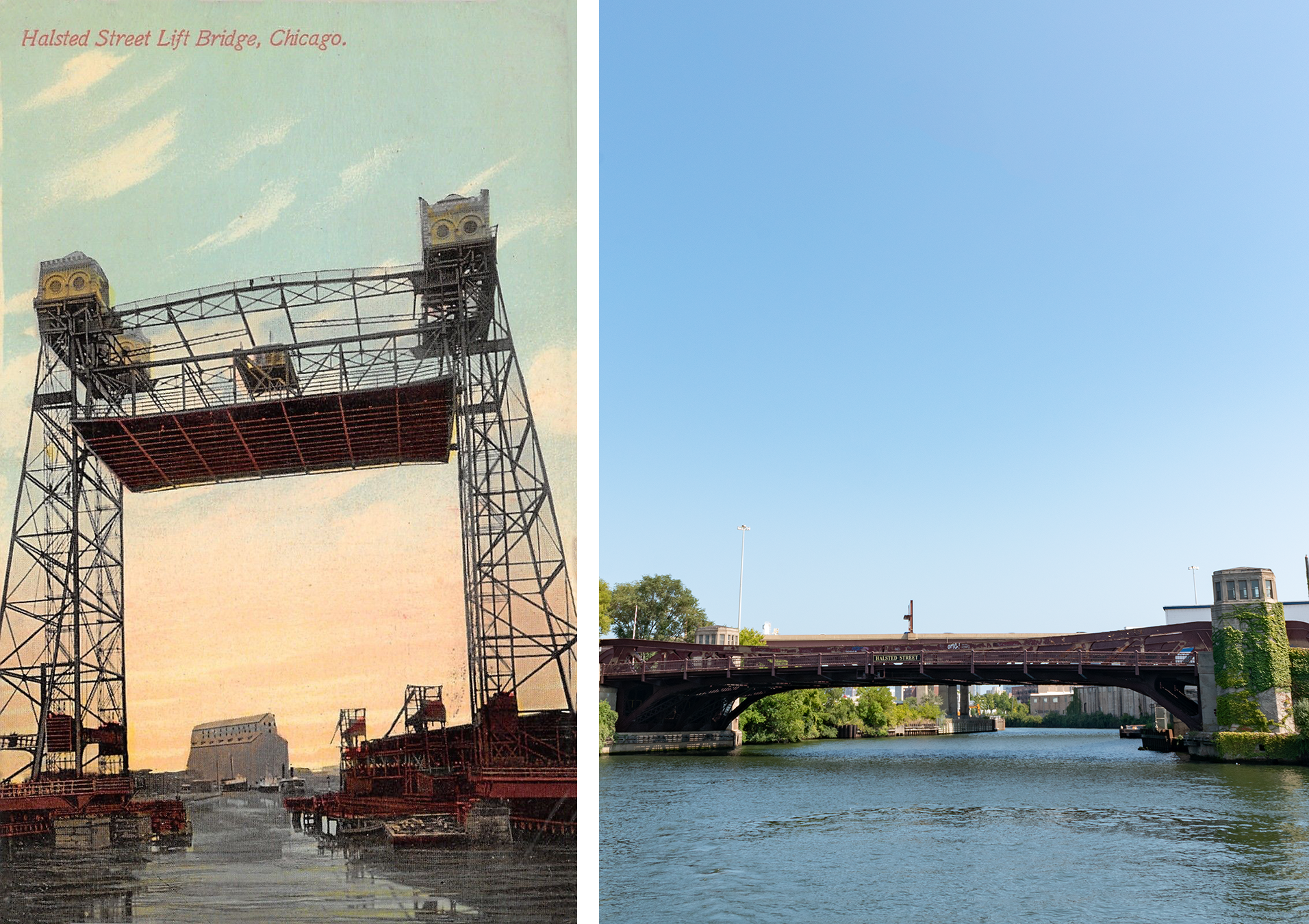

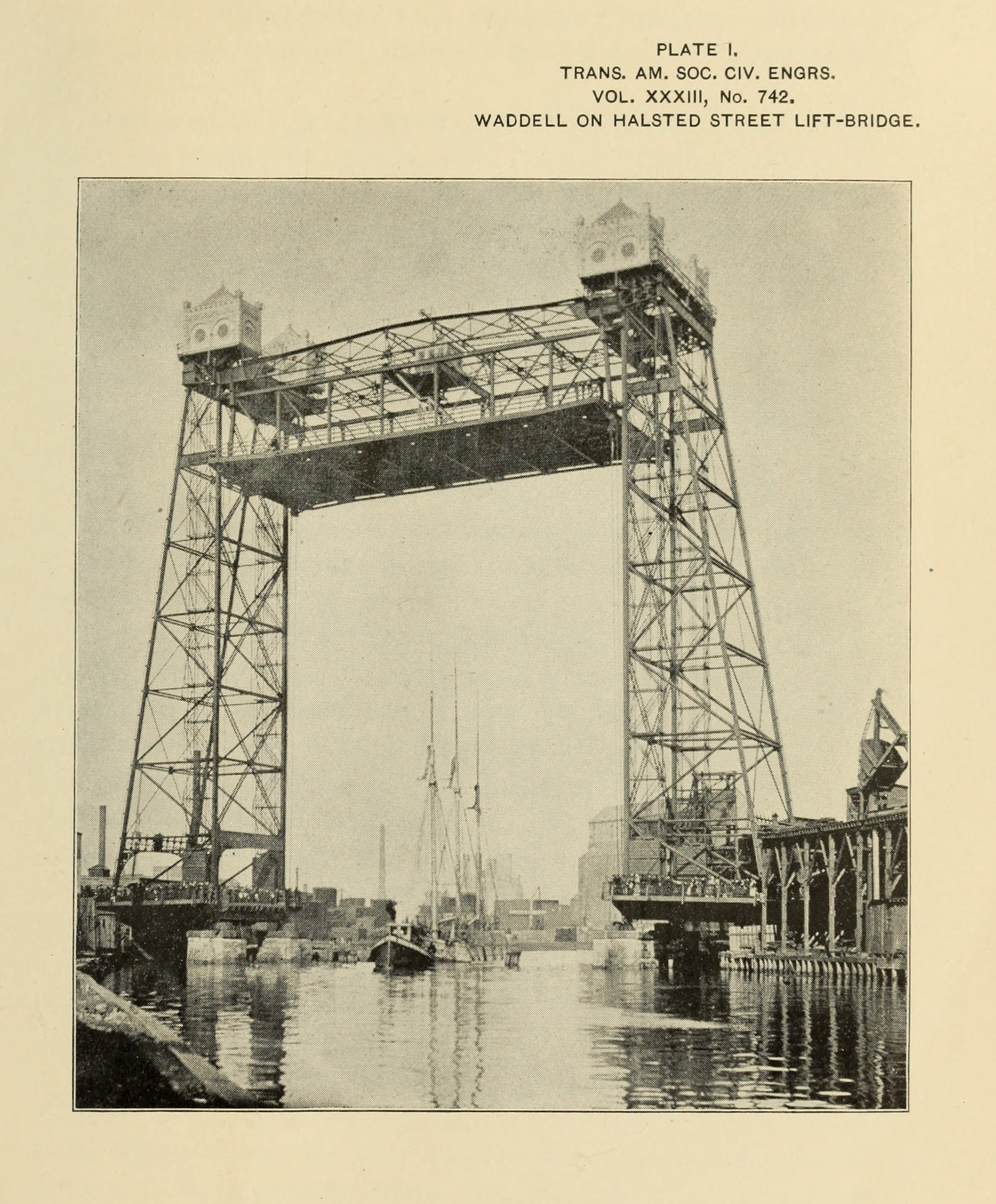

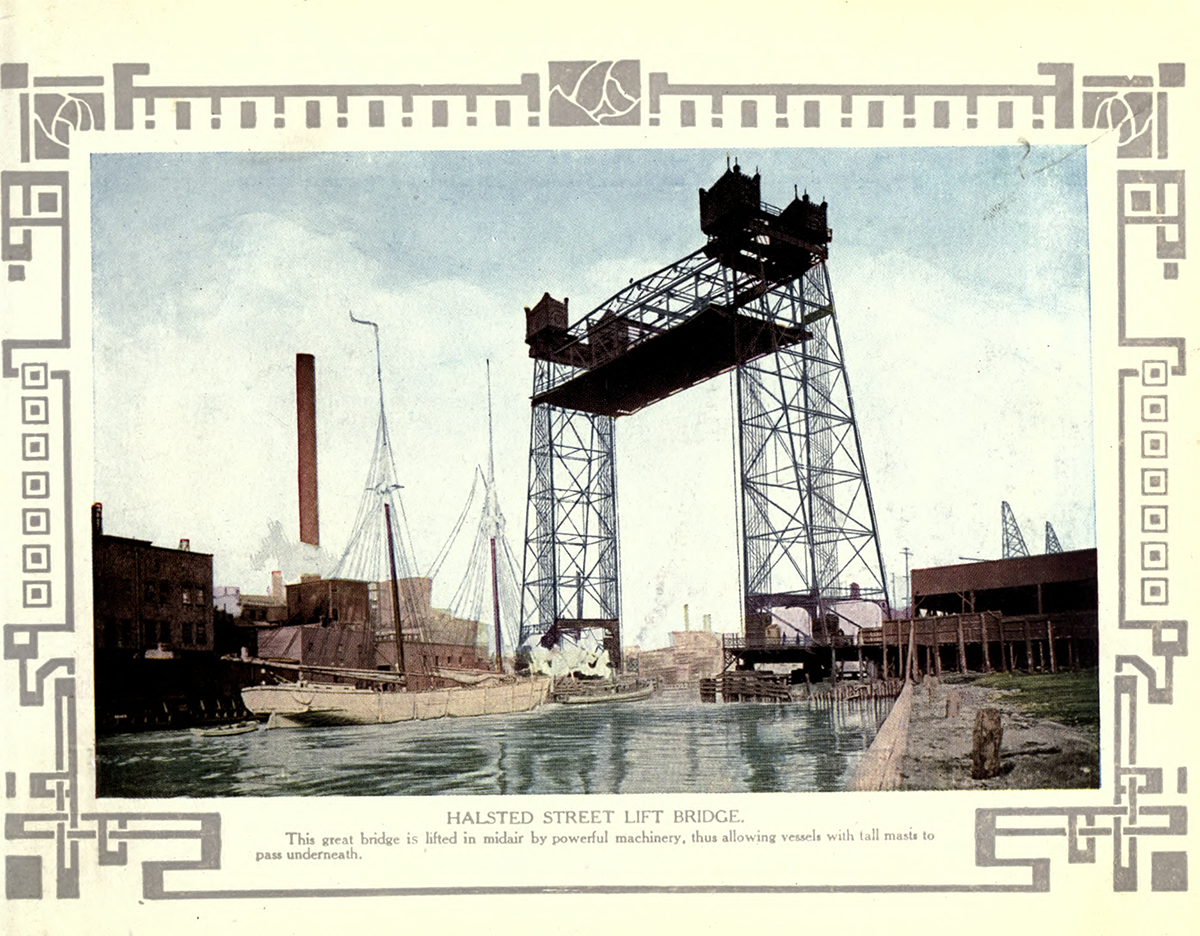

This is neat–Chicago’s old Halsted Street Lift Bridge was the first modern vertical lift bridge in the world, designed by J.A.L. Waddell and completed in 1894. Developed to replace the swing bridge as steam displaced sails and vessels grew larger, the vertical lift bridge ended up being a kind of Betamax to the bascule bridge’s VHS...clearly illustrated by this bridge’s replacement with the current bascule bridge in 1934.

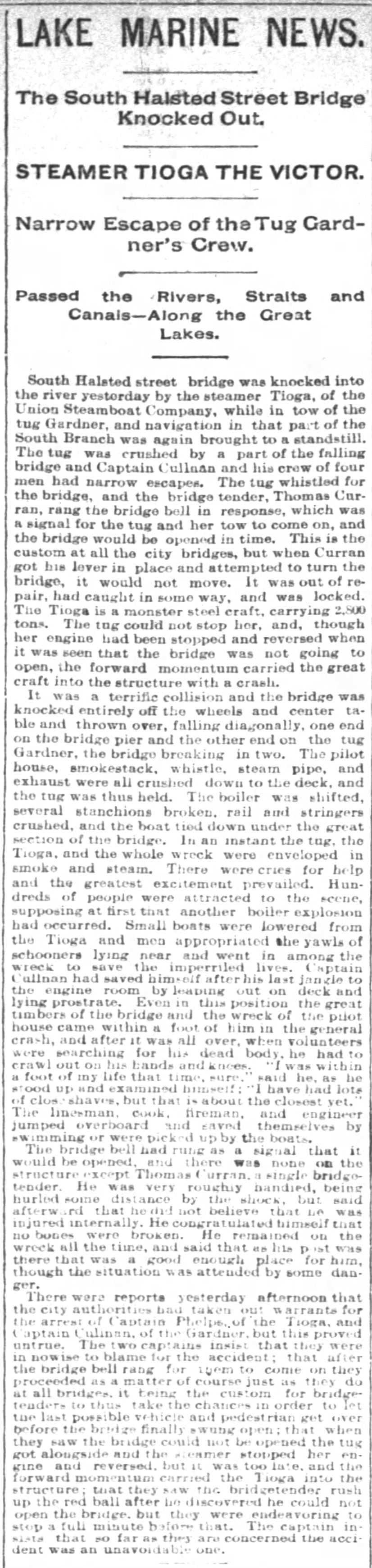

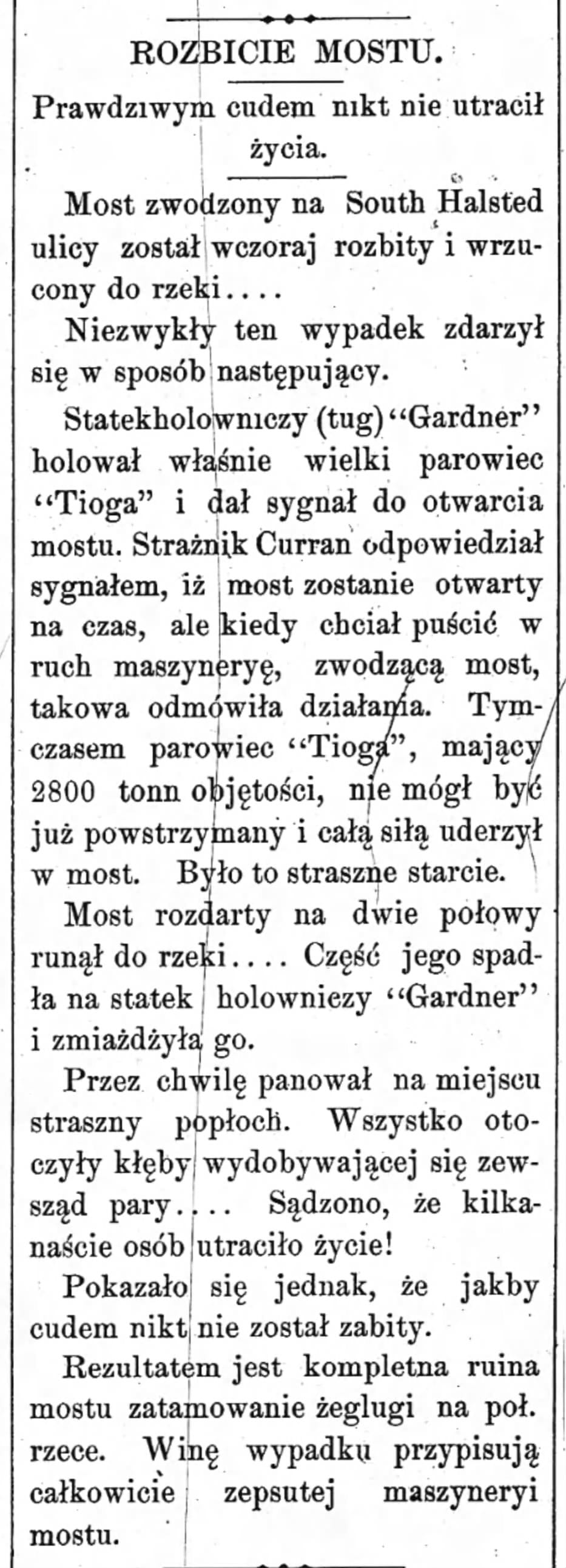

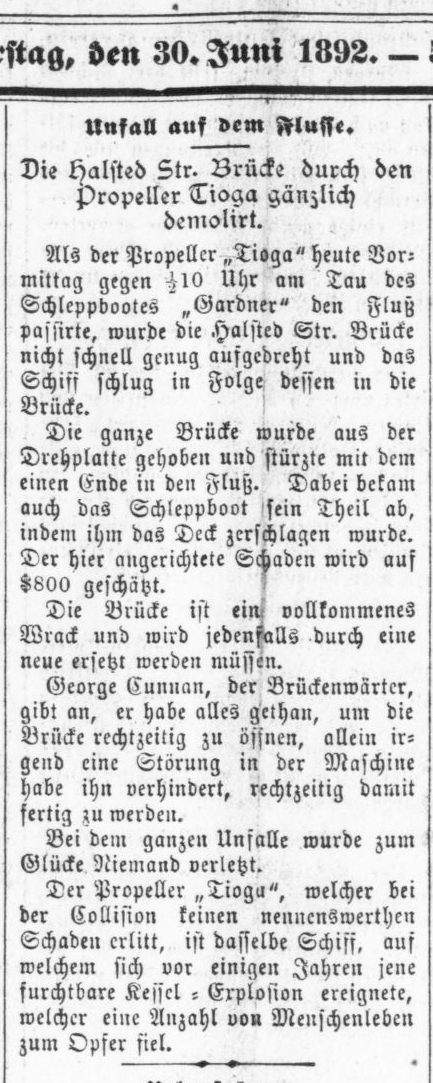

That a vertical lift bridge ended up here at all was the unlikely result of a handful of accidents and failures. First, its predeccesor–the Halsted Street Swing Bridge–was destroyed when the steamer Tioga collided with it in 1892 (the Tioga was a cursed ship–only two years prior, 30 people died when the ship caught fire).

1892 articles about the Tioga hitting the old Halsted bridge

Waddell, already an established bridge builder with a host of patents to his name, had designed a novel vertical lift bridge for the Duluth Ship Canal in the 1890s, but the Department of War–charged with approving plans for all new bridges over navigable waterways to ensure they stayed "reasonably free, easy and unobstructed"–nixed it.

After the Tioga destroyed the previous Halsted St. Bridge, Waddell recycled his Duluth design for Chicago. Opposed by local engineers angry they didn’t get the commission and with the city government in turmoil, the city attempted to stop construction…but in typical Chicago fashion, the city would have had to pay the full contract price for the bridge whether it were built or not, so construction continued.

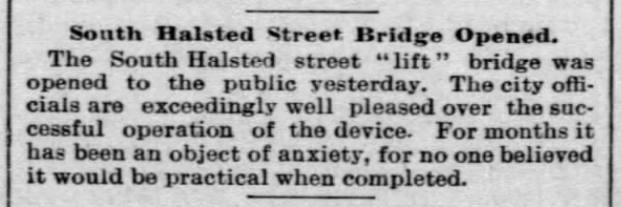

1892 article about plans for the new lift bridge | sketch of the new bridge | 1894 articles about its opening and doubts about it | 1915 photo, MWRD | early 1900 photo, Detroit Publishing Co., Library of Congress

At the time, the vertical lift bridge was an innovation. In contrast to a swing bridge, which requires a central pier that interrupts the channel and presents a navigational hazard (bobtail swing bridges on smaller spans excepted), a vertical lift bridge creates one wide channel. Since there’s no need to clear an area for the span to swing, they also enabled increased dock space that industry could use for loading and unloading. They were also faster than a swing bridge–a lift bridge only needs to be raised just high enough for a ship to pass, rather than a swing bridge that must be fully opened.

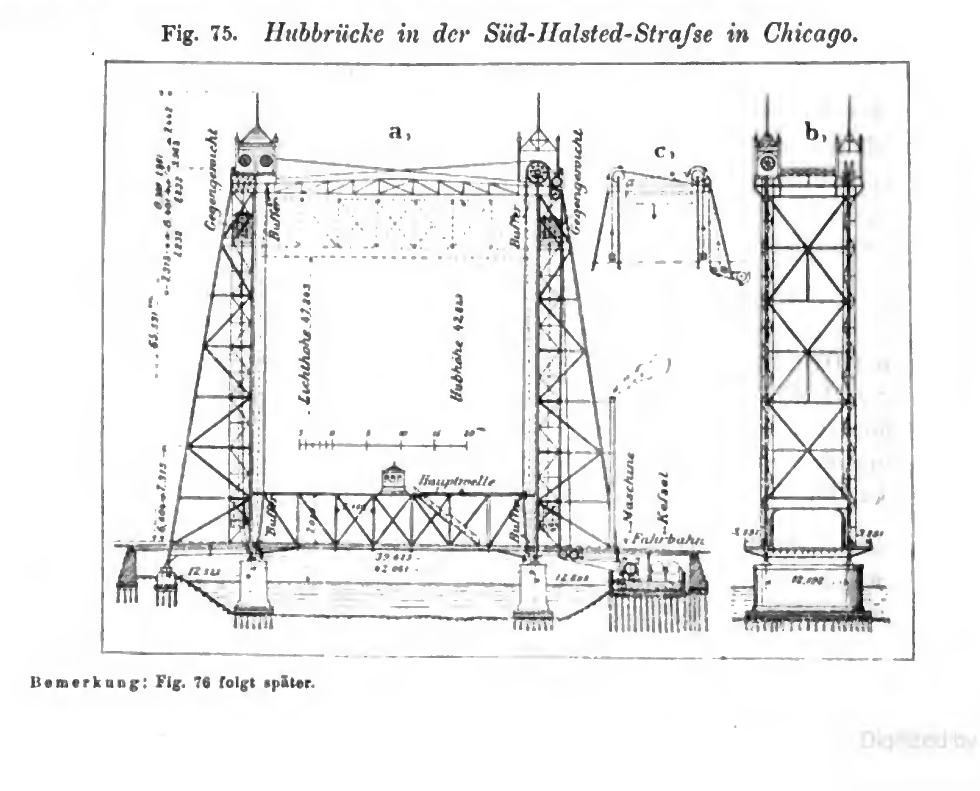

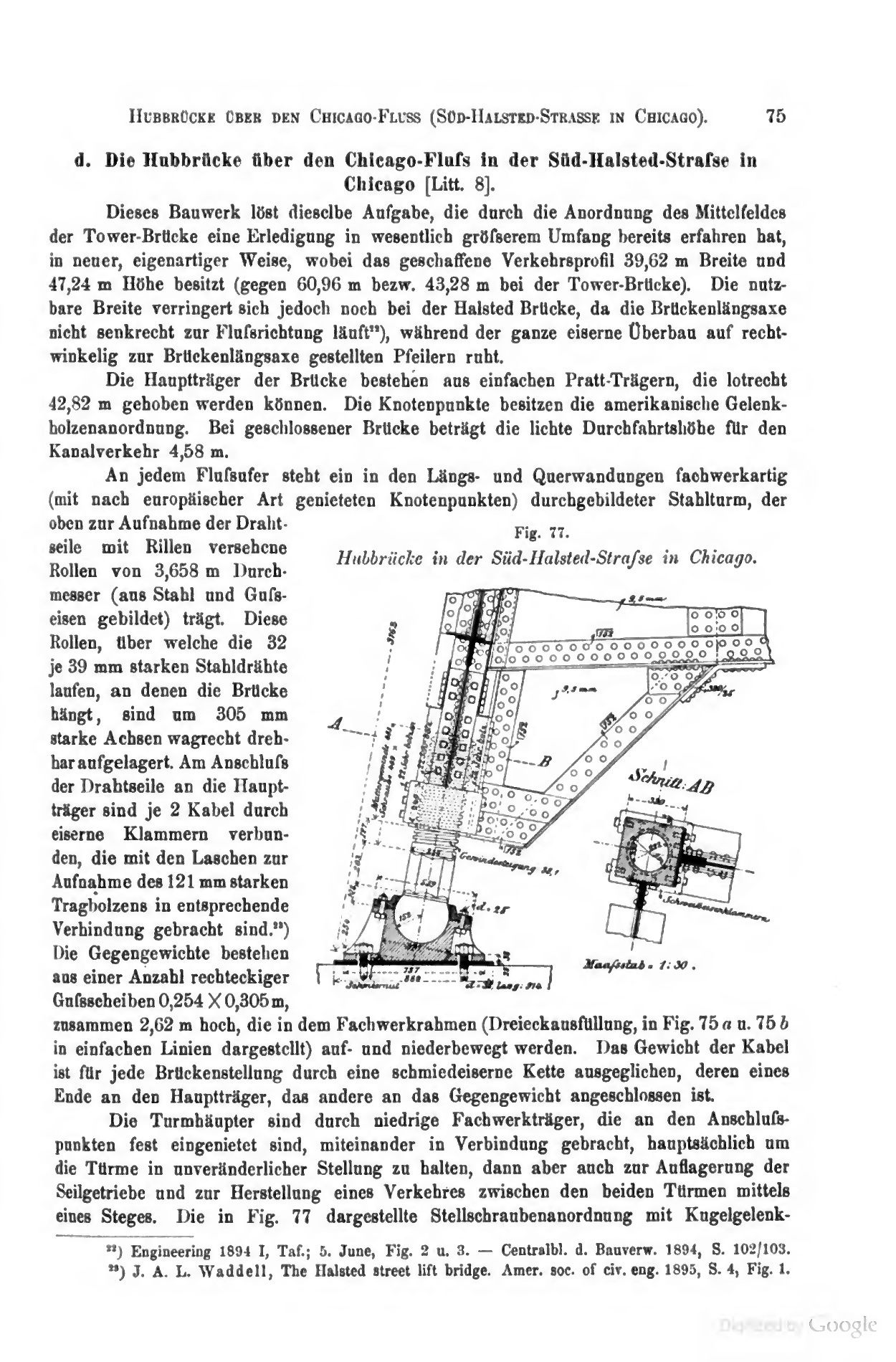

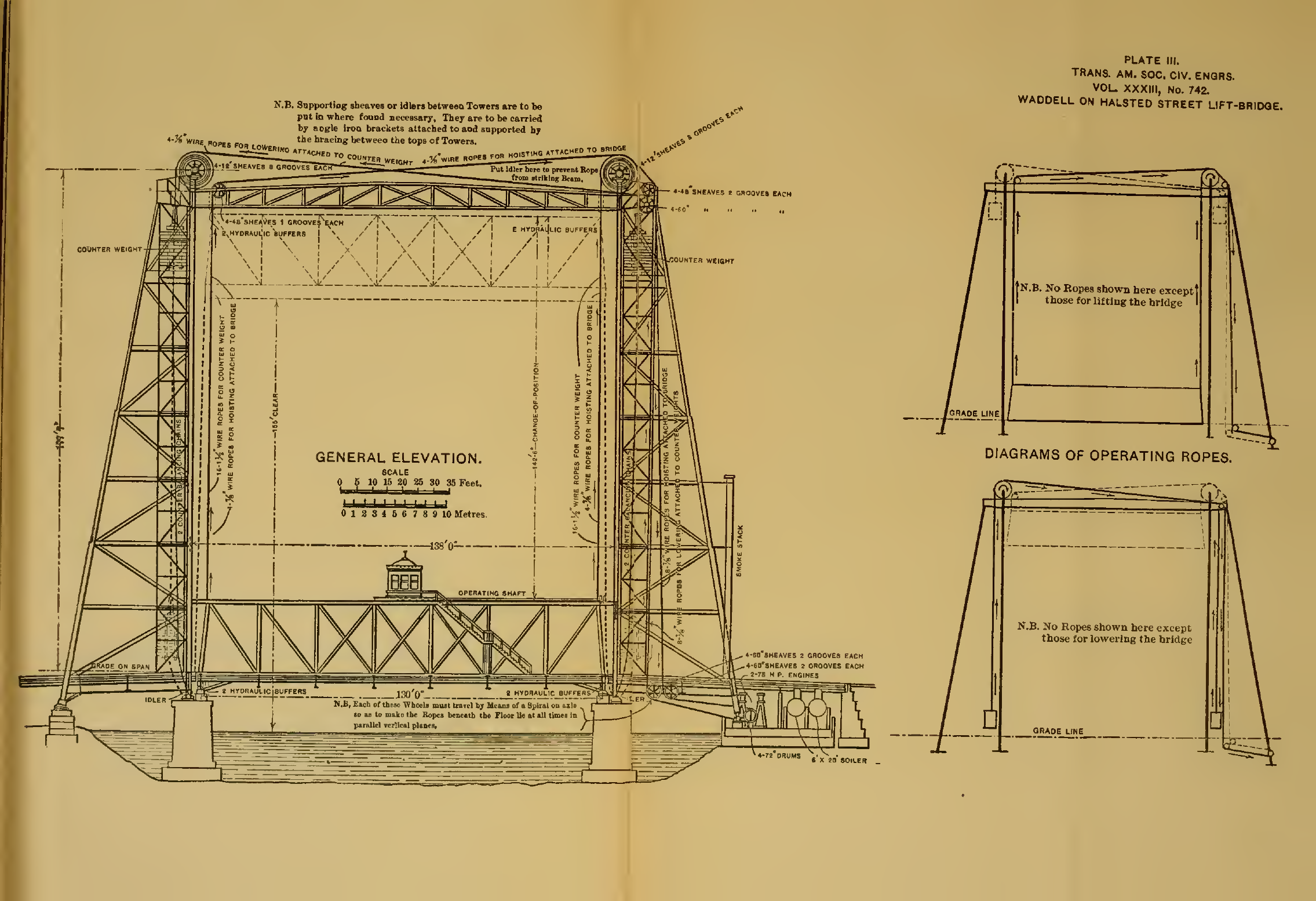

In "Bewegliche Brücken", Fortschritte der ingenieurwissenschaften, 1897, the Internet Archive | In the American Society of Civil Engineers, 1894, the Internet Archive

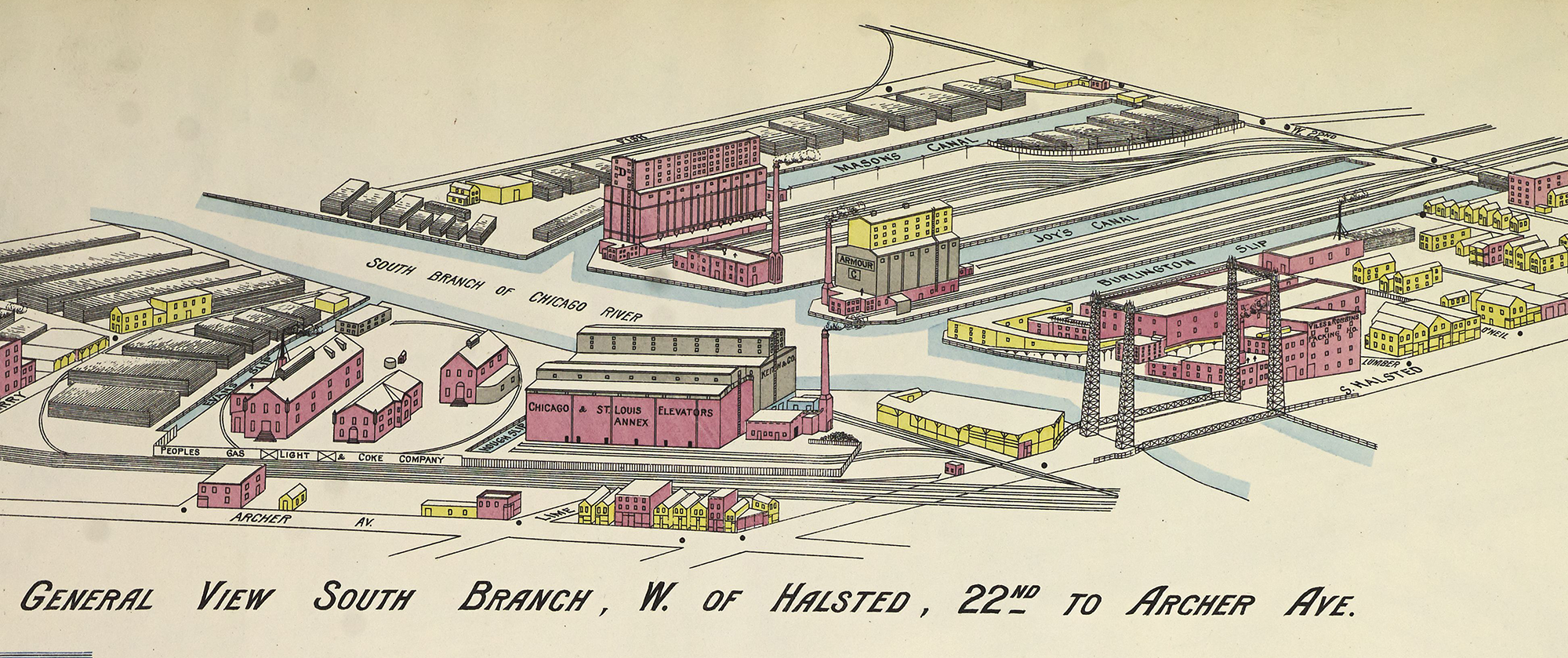

This busy section of the Chicago River was the perfect test site for Waddell's novel design: a narrow, crooked river lined with industry. It worked well enough as a movable bridge, but as advertisement for lift bridges as the river crossing of the future it was less effective. It took another 15 years before another vertical lift bridge was built in the US. They took off briefly in the 1910s, and Waddell’s firm ended up designing at least 74 (and in 1930, the bridge at the Duluth Ship Canal was converted to a vertical lift bridge after all). Chicago still has a handful–the Canal Street Railroad Bridge on the Chicago River and a clutch on the Calumet River–but it turned out that the vertical lift niche was pretty small and bascule bridges won out.

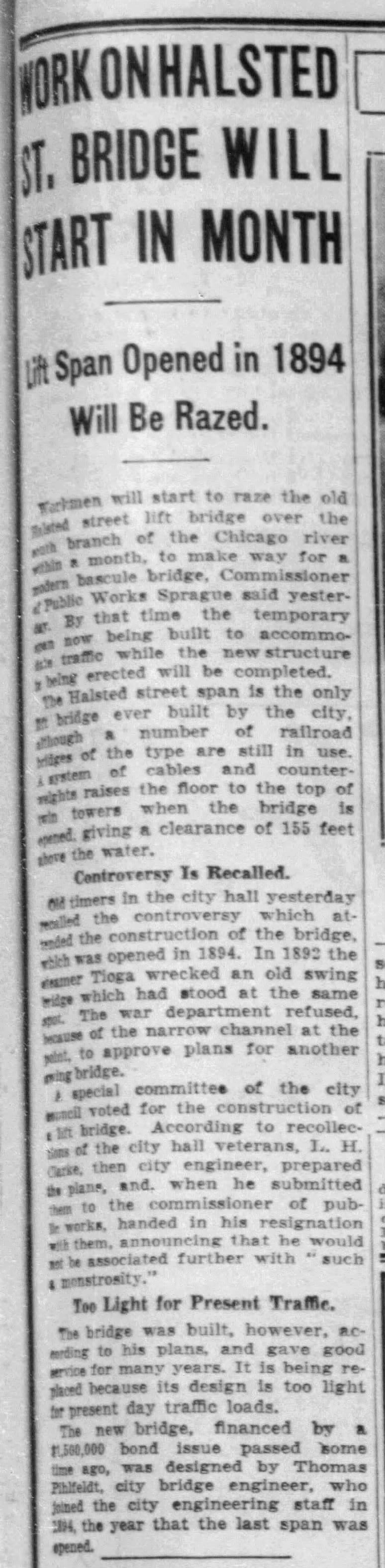

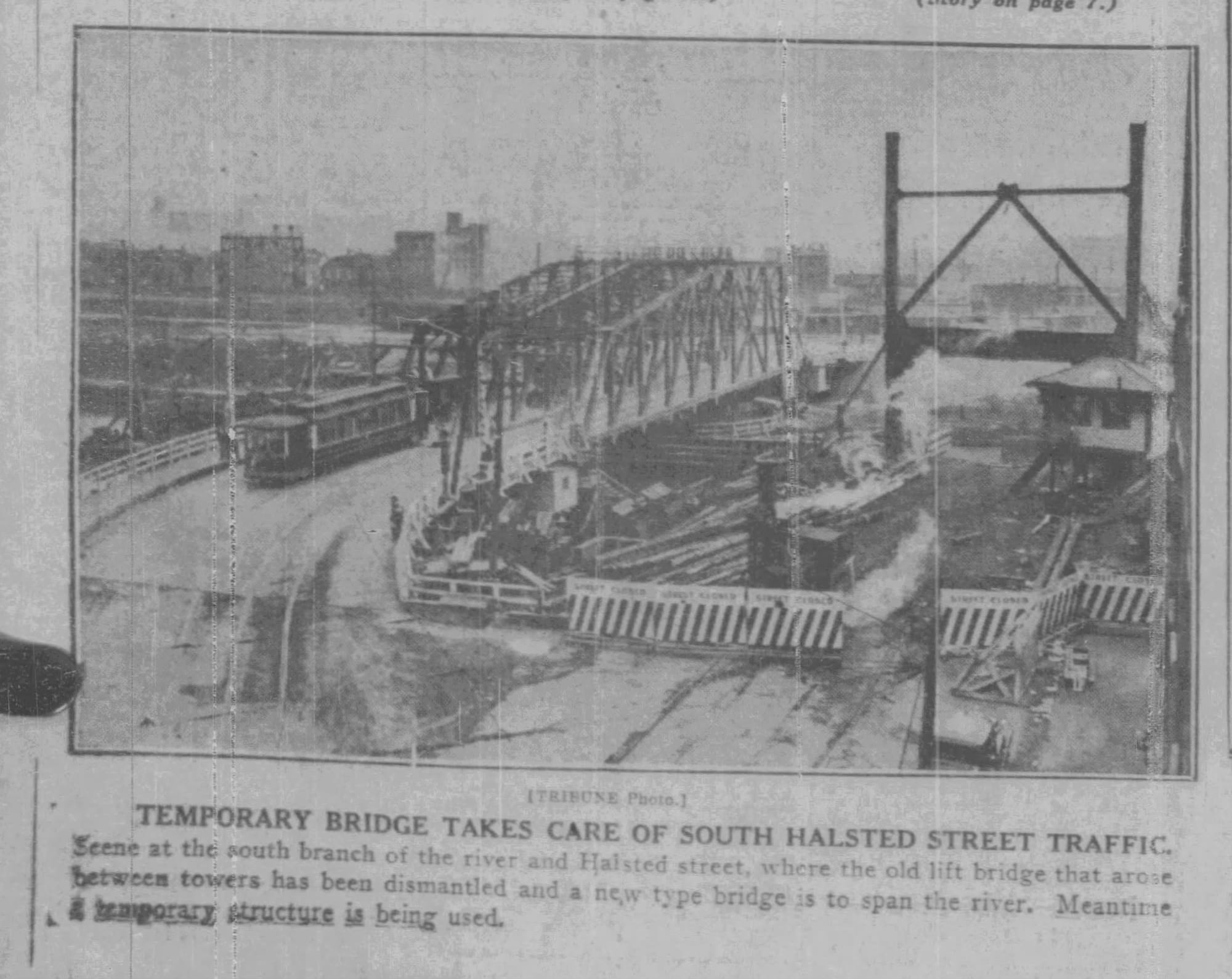

1931 and 1932 articles about the removal of the lift bridge and its temporary replacement

Incapable of handling the heavier loads of personal car traffic and trucks, the city dismantled the Halsted Street Lift Bridge in 1932. The current pony truss bascule bridge opened in 1934.

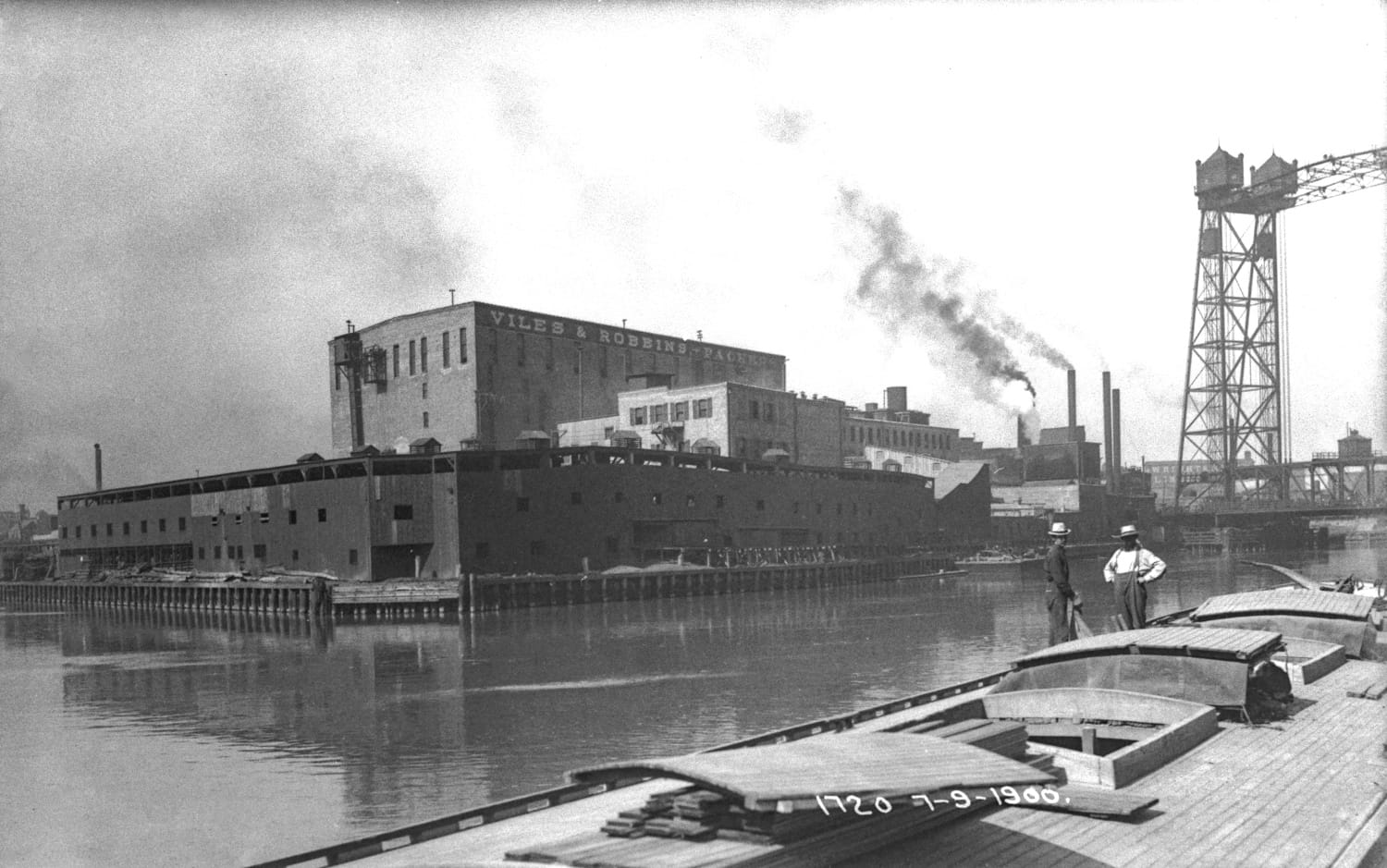

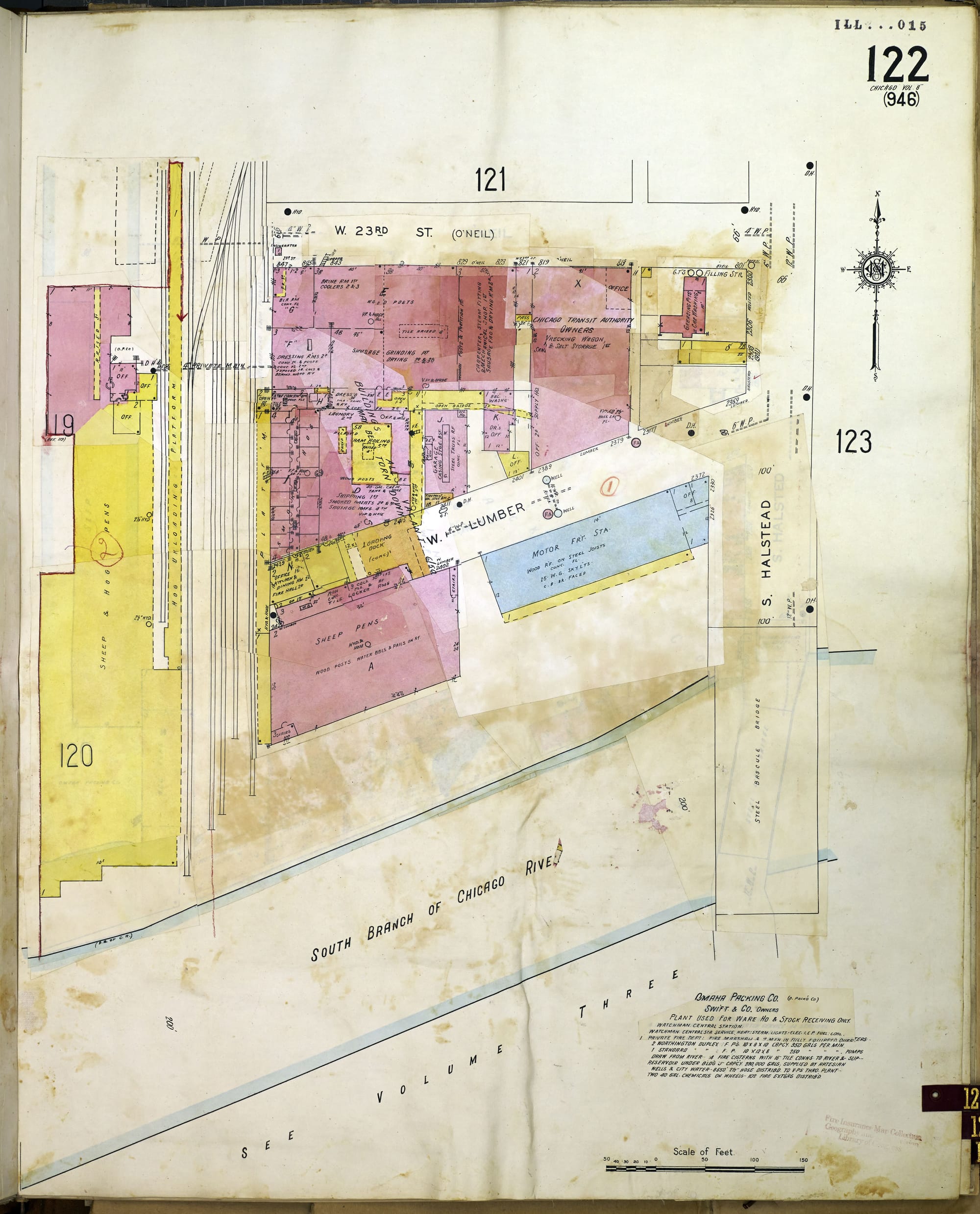

It was the industrialization of the South Branch of the Chicago River that created the demand for a vertical lift bridge–industry like the Omaha Packing Co. slaughterhouse, on the north bank of the river (left side of the postcard).

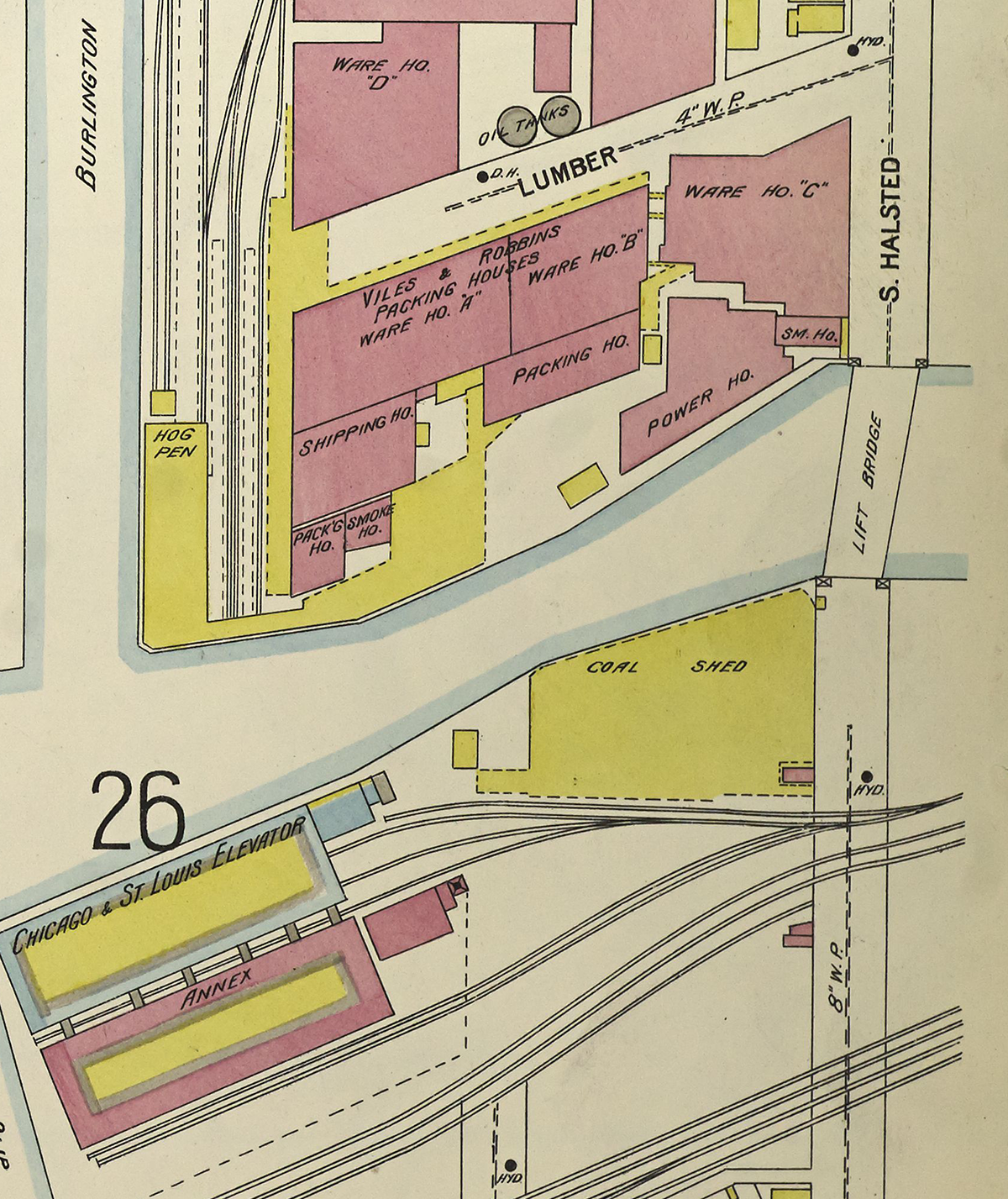

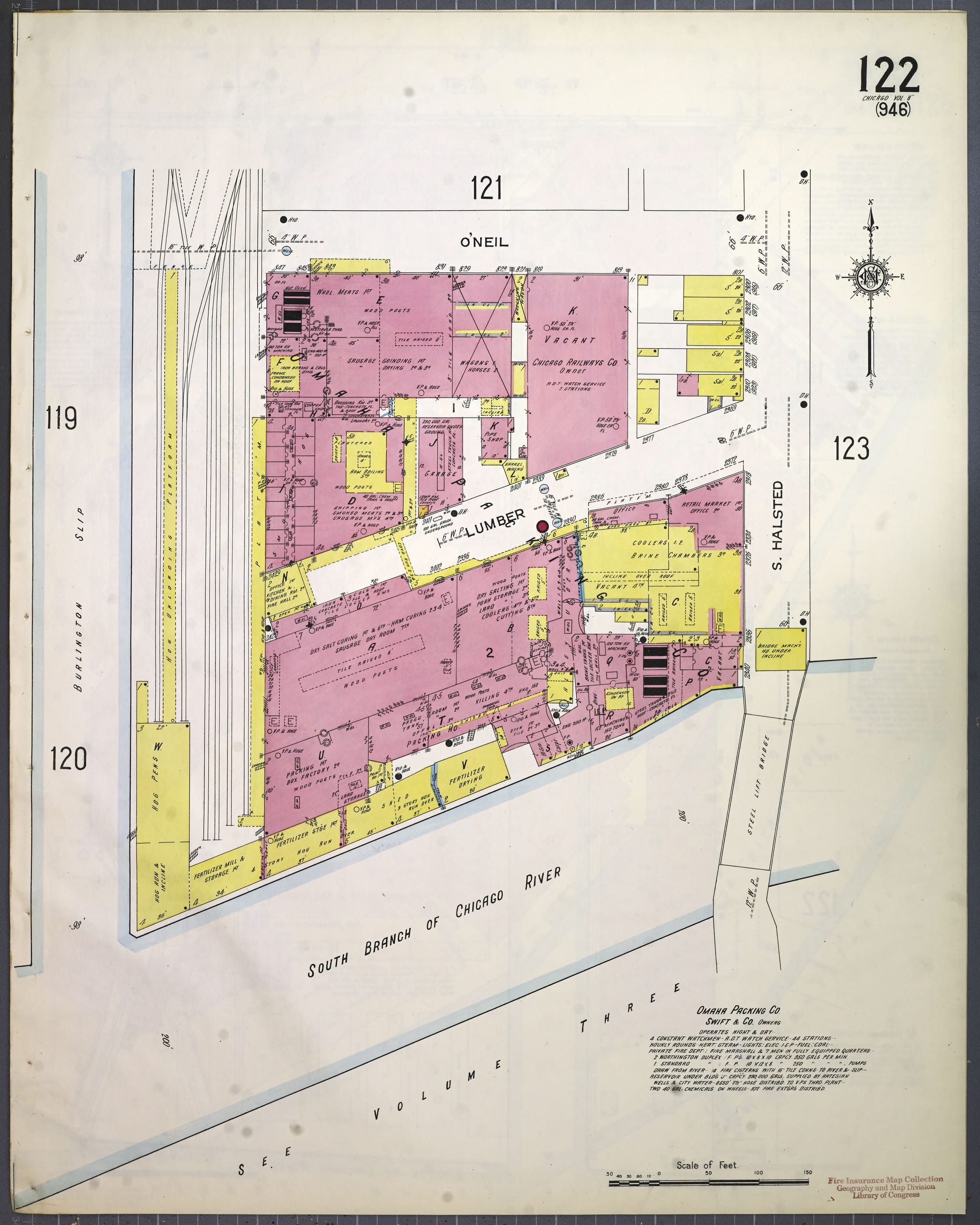

Built for the firm of Viles and Robbins in the 1880s and 1890s, then renamed Omaha Packing Co., the complex to the northwest of the Halsted Street lift bridge was one of a handful of slaughterhouses outside the Union Stockyards. With rail and river shipping delivering livestock and material, Omaha Packing Co. processed pigs, cattle, and sheep. It was eventually bought by meatpacking giant Swift & Co.

1900 photo, MWRD | 1901, grain elevator fire insurance map | undated photo | 1901, grain elevator fire insurance map | 1914 Sanborn map | 1950 Sanborn map

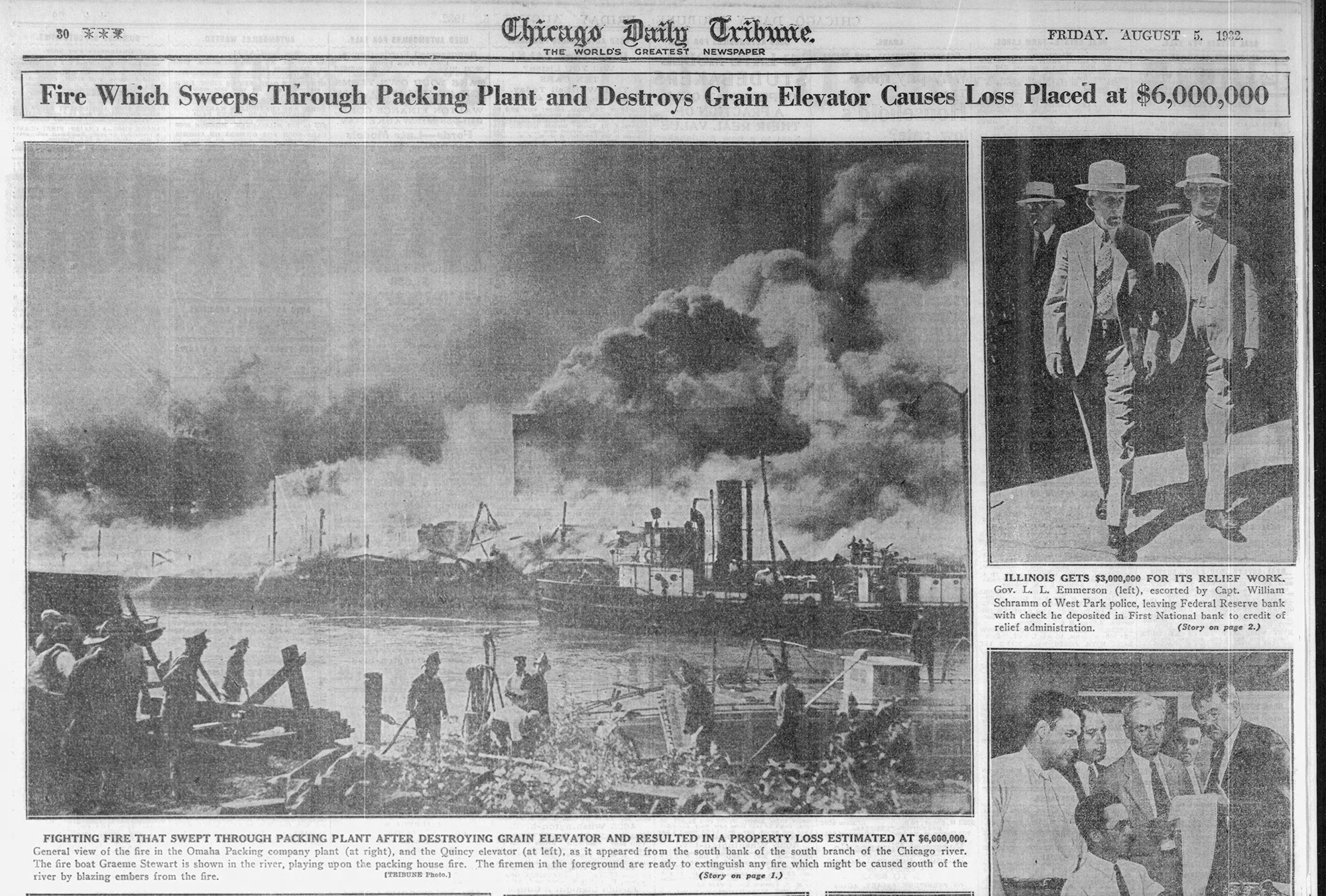

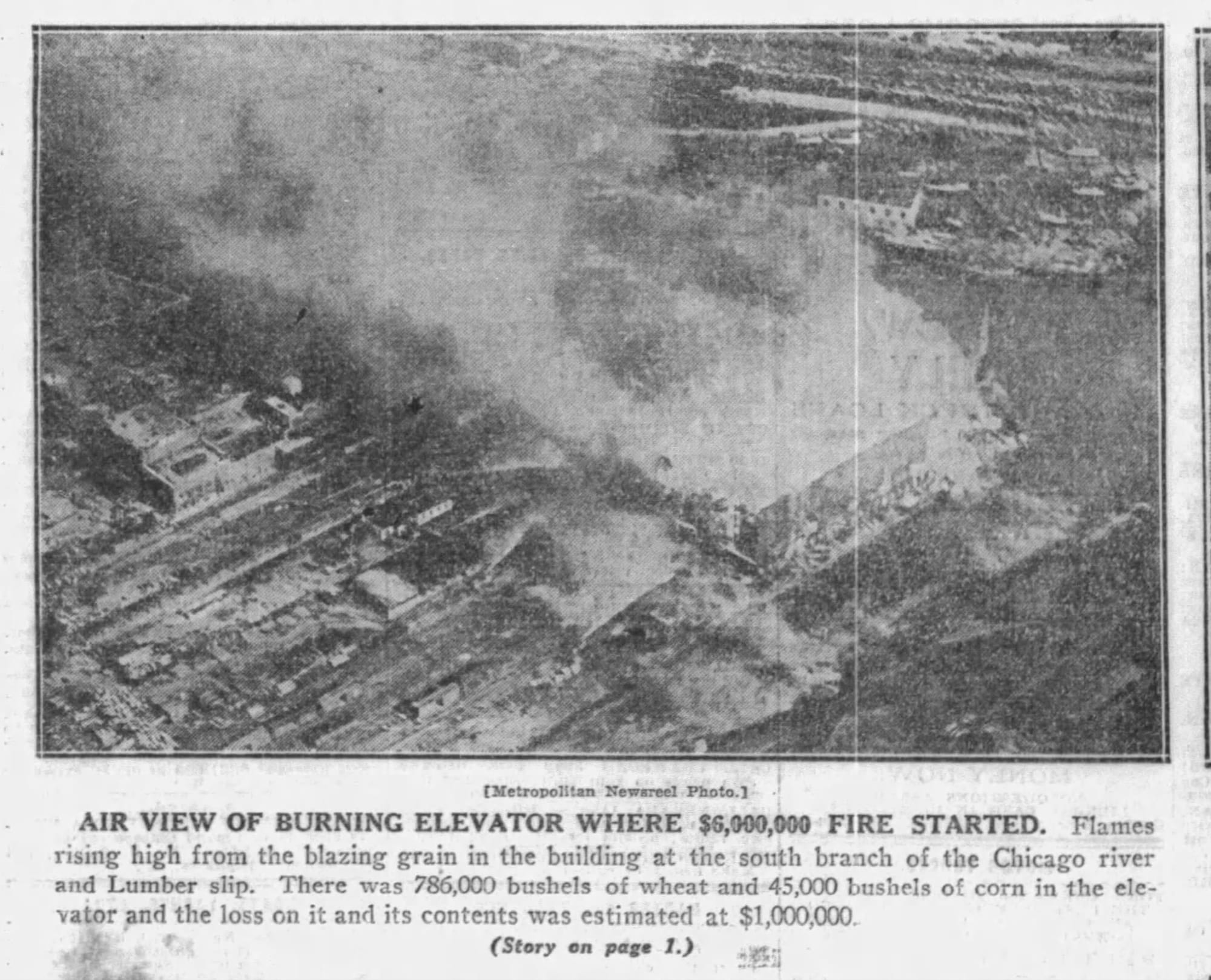

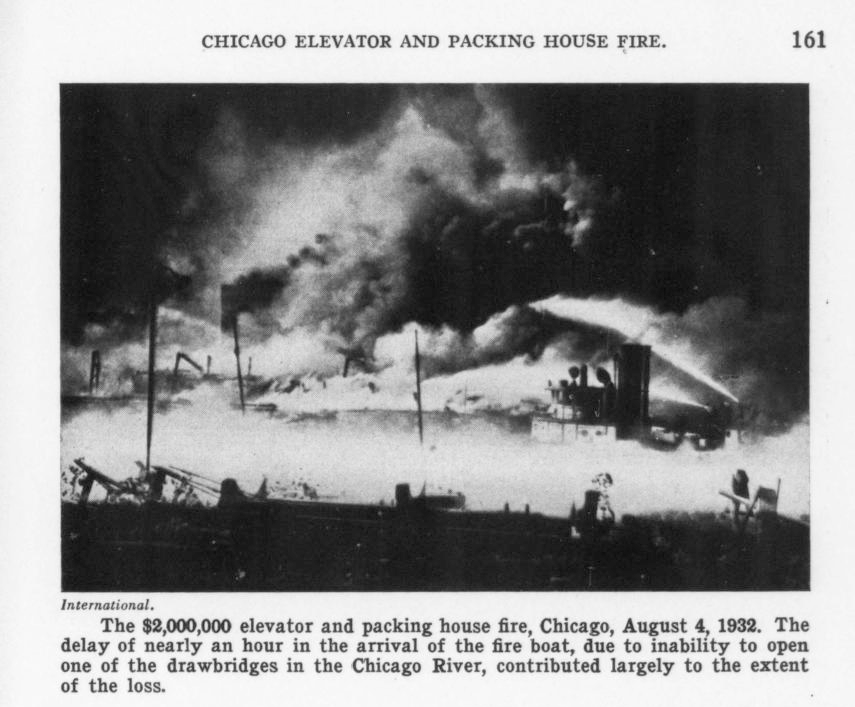

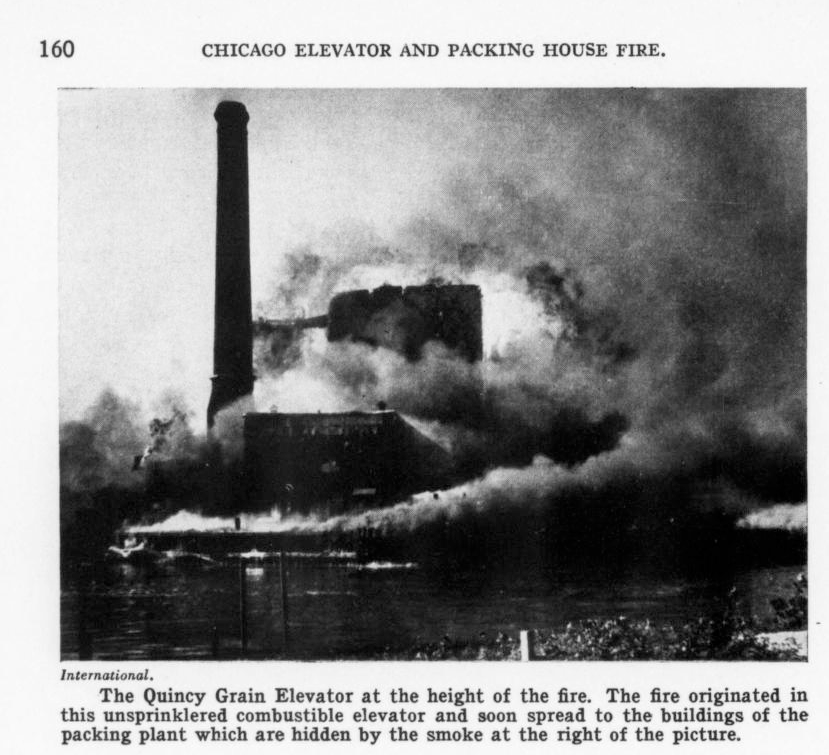

Like most of these facilities, Omaha Packing burned and rebuilt multiple times, with big fires in 1903 and 1932. When the complex’s lard house burned in the 1903 fire, Chicago Live Stock World headlined an article, “LARD IS CREMATED”–that smell must’ve been something.

1897 lard fire | 1903 fire | 1929 fire | article on the 1932 fire

Ironically, a vertical lift bridge was partially responsible for the plant burning in the 1932 fire. The fire department mobilized quickly to fight the enormous fire, which started in the Quincy grain elevator next door, but the responding fireboat was delayed when the bridge tenders struggled to lift the Canal Street Railroad Bridge.

The fire partially destroyed a plant that was already in decline, and by the 1940s parts of the Omaha Packing Co. plant were already being sold off for salvage. Swift & Co. completely closed the plant in 1954–but a small portion of the complex still stands, home to a stone fabricator.

1932 article on memories of the area | 1942 ad for a wrecking sale of the plant | 1954 article on the plant closure

Production Files

Further reading:

- "Dr. J. A. L. Waddell's Contributions to Vertical Lift Bridge Design", by William E. Nyman

- "Development of the Vertical Lift Bridge: Squire Whipple to J. A. L. Waddell, 1872–1917", by Francis E. Griggs, Jr.

- Bridge Engineering by JAL Waddell

- "The Evolution of Vertical Lift Bridges", by Henry Grattan Tyrell

- "The Halsted Street Lift Bridge" by JAL Waddell in the American Society of Civil Engineers, 1894

- "The Lift Bridge at Halsted Street" in the Street Railway Review, 1894

There were some teething issues when the new bridge opened in 1894.

Articles about people and streetcars getting stuck on the raised lift bridge in 1894 and 1896, as well as something falling from it that year

Member discussion: