A beloved Venetian-inspired art palace in Copenhagen built by the Danish public sector to house the donated art collection of a brewery oligarch, located on a road widened during the car-brained 1950s…which still carries more than twice as much bike traffic as cars during rush hour.

Glyptoteket also exemplifies just how quickly Copenhagen—and other rapidly modernizing cities in Europe and North America—built themselves up and changed. Once a swampy empty lot on the outskirts of Copenhagen’s downtown core, within thirty years of its 1897 opening Glyptoteket was a world-class art museum that had already expanded twice.

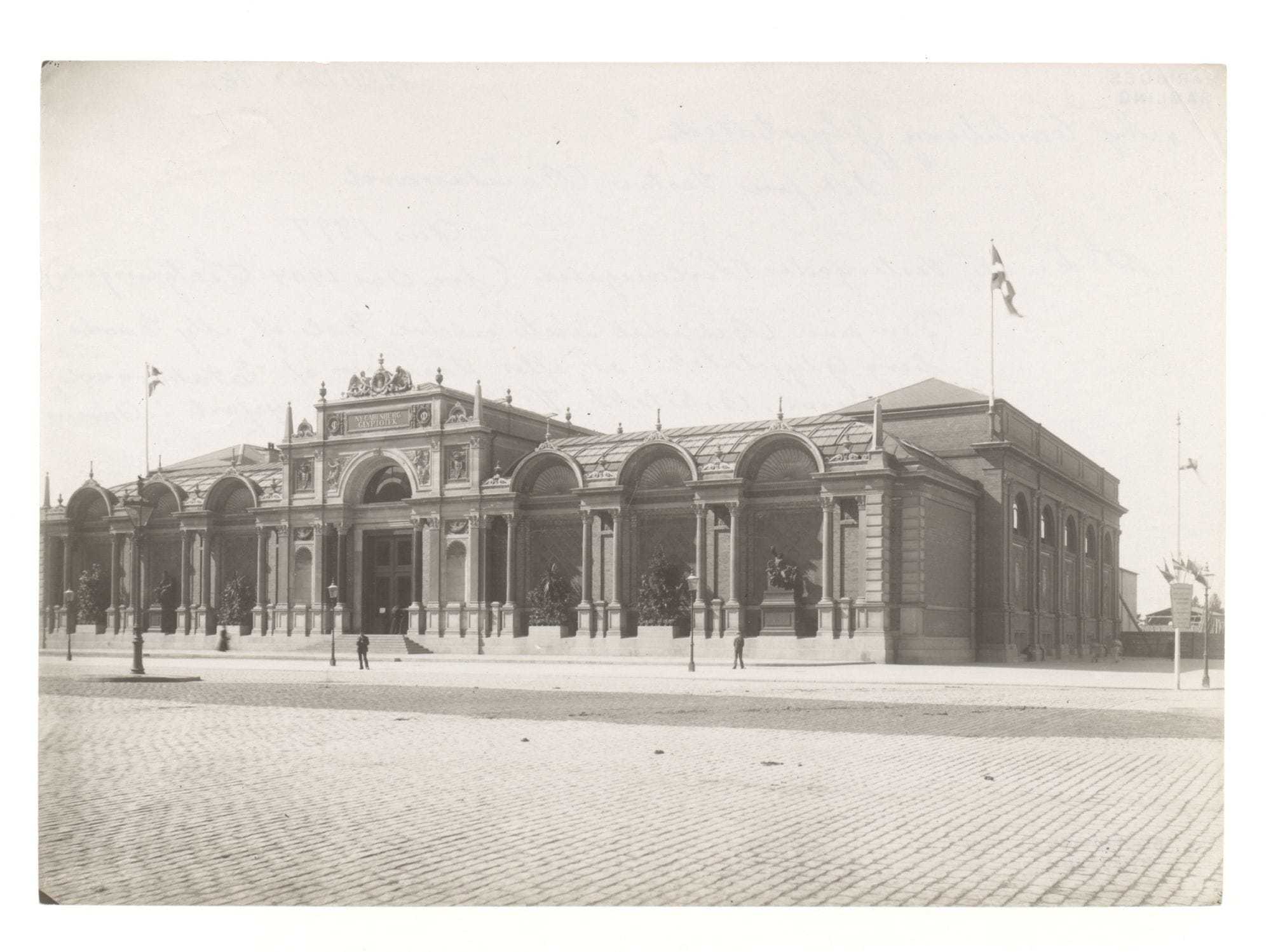

So, what’s changed? The two flagpoles on the corners have been removed and the building lost some finials, but otherwise Glyptoteket itself has barely changed at all. Some of the outdoor sculpture has been rearranged, with the large pieces on plinths in the alcoves moved elsewhere. The big change is in the streetscape—H.C. Andersens Boulevard (which would have been known as Vestre Boulevard when this postcard was published) was widened to swallow up more of the sidewalk, bike lanes were added, the cobblestones were paved over, and a small grassy median park was added in front of Glyptoteket.

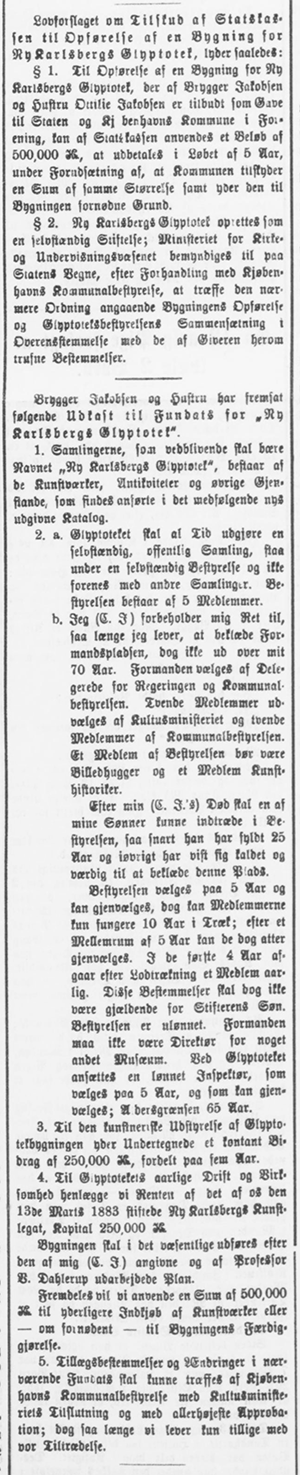

Brewery tycoon Carl Jacobsen, son of the founder of Carlsberg, kicked off the process that became Glyptoteket in the 1880s with an offer to donate (initially, part of) his personal art collection to create an independent, publicly-accessible museum.

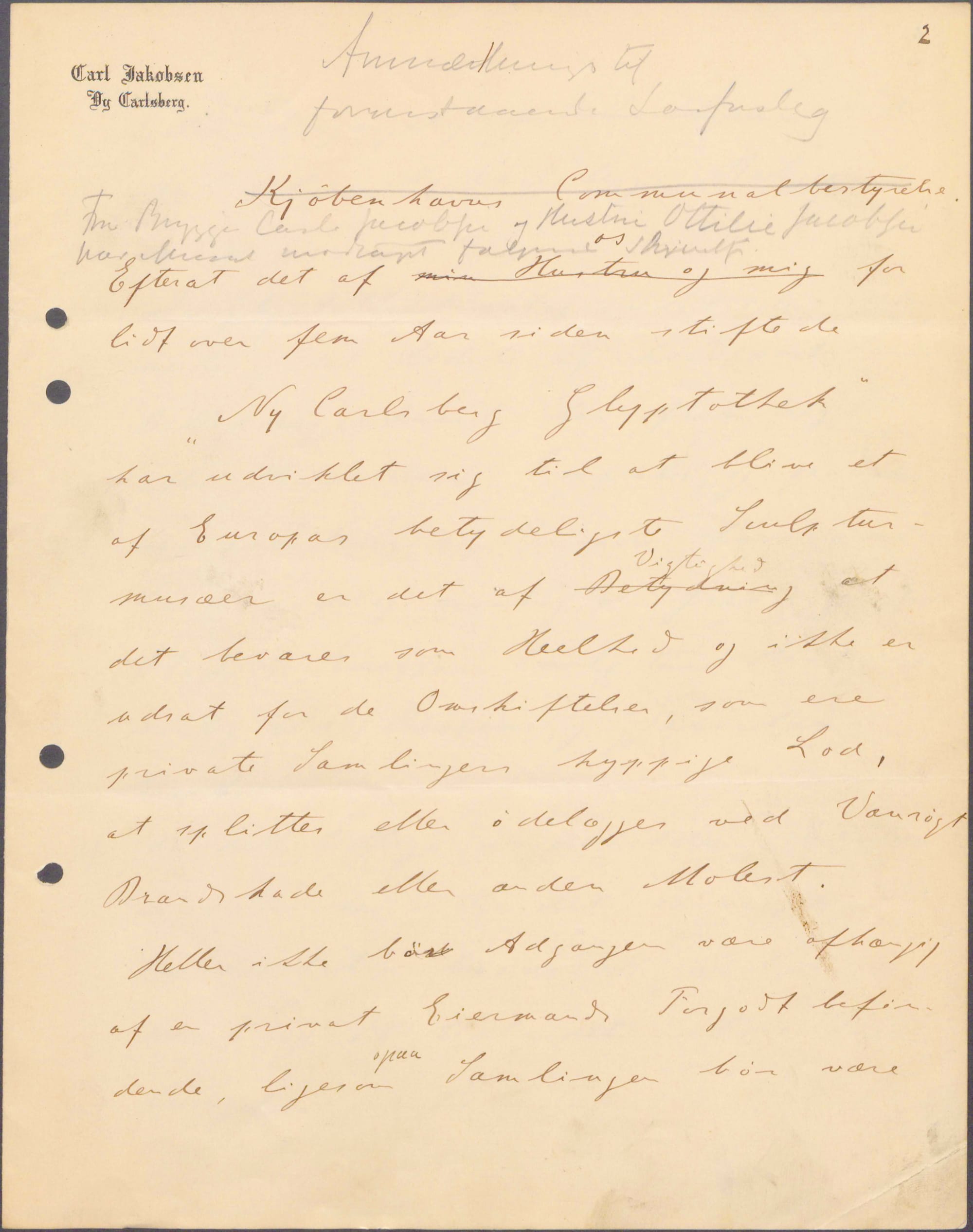

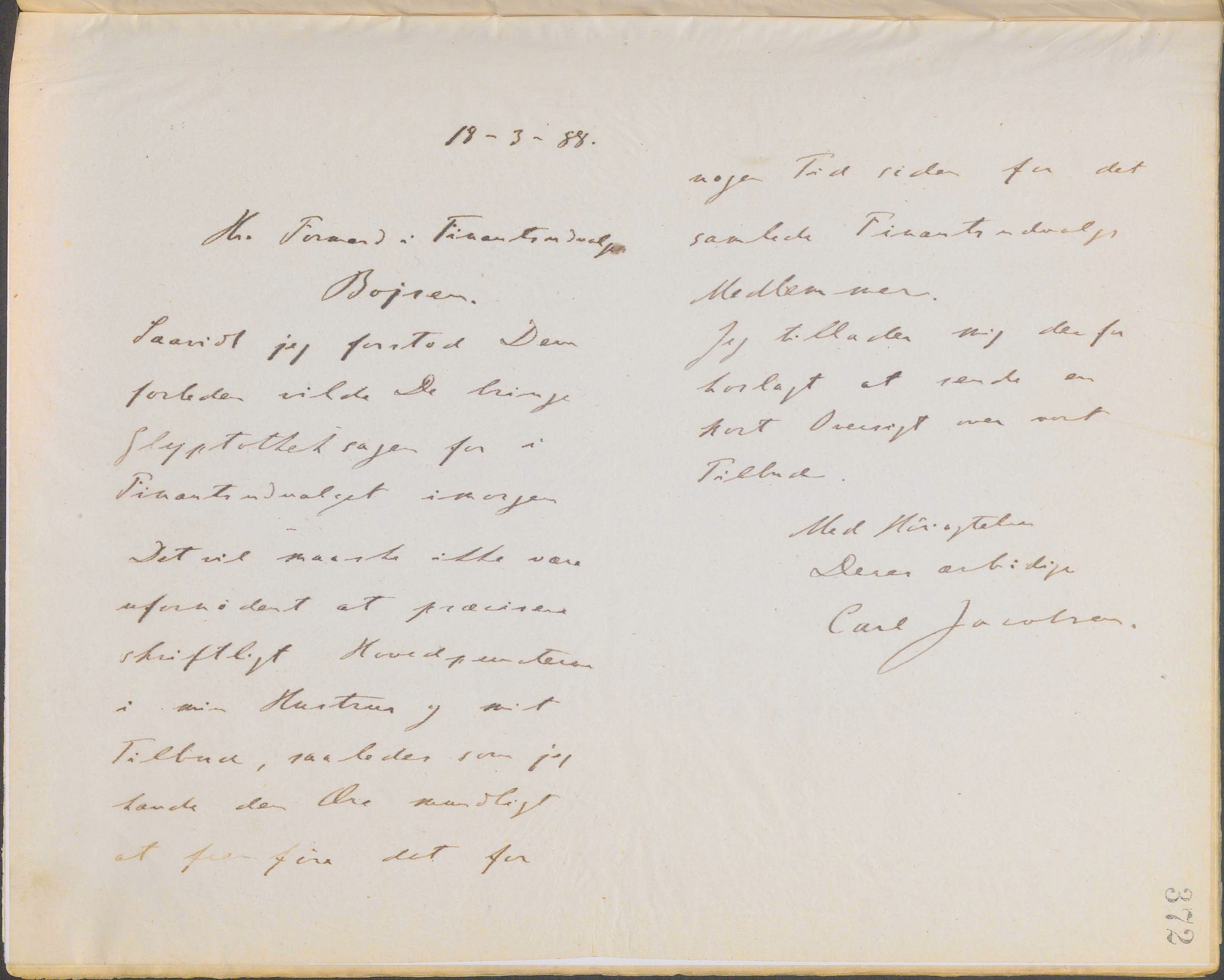

Carl Jacobsen letter to the Municipality of Copenhagen regarding the gift deed, 1888, Carl Jacobsens Letter Archive, New Carlsberg Foundation | Carl Jacobsen letter to the Finance Committee about his proposal, 1888, Carl Jacobsens Letter Archive, New Carlsberg Foundation

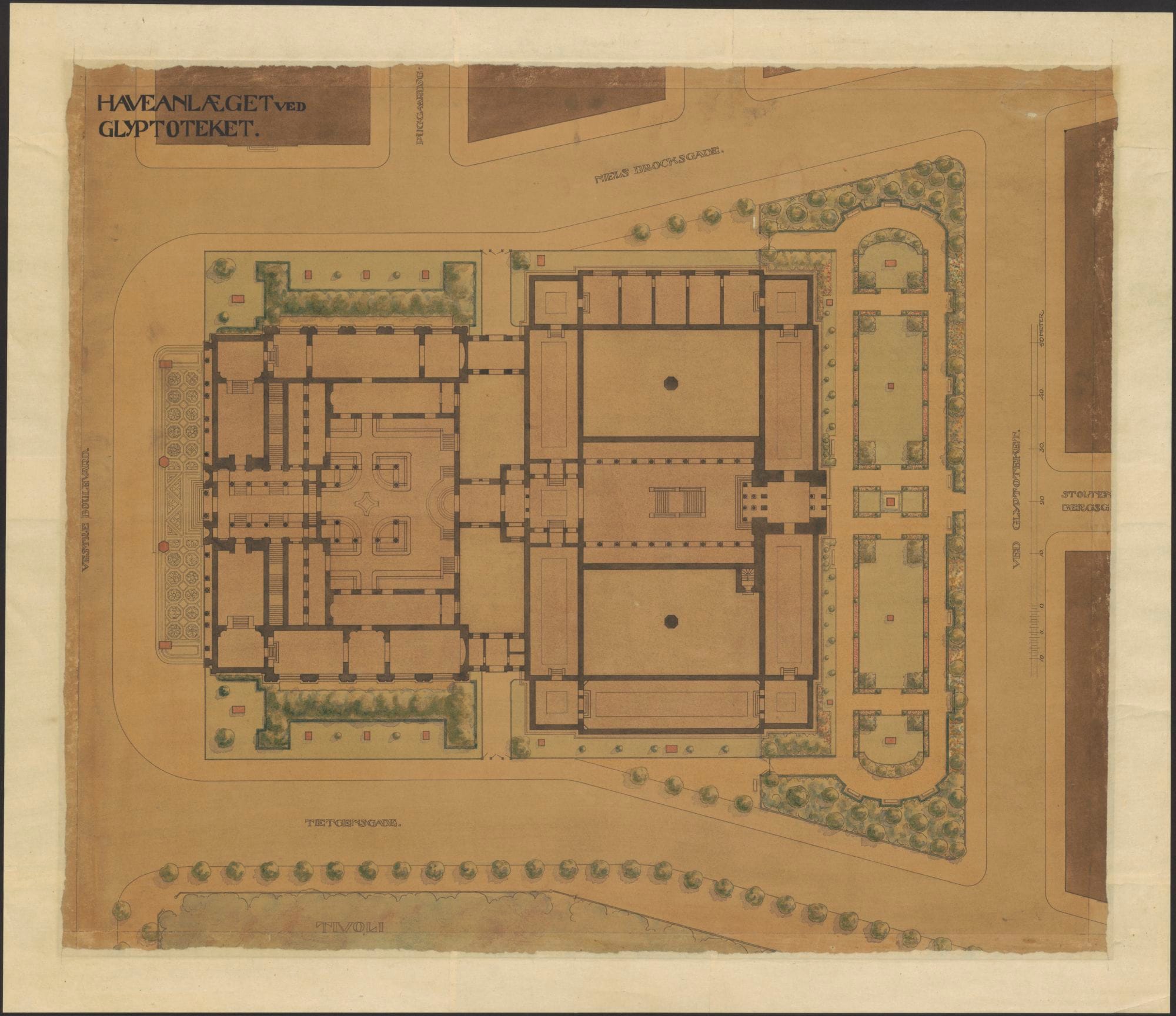

Jacobsen provided three major conditions for his donation. One, the Danish state and the municipality of Copenhagen would donate the land. Two, they would pay for a big chunk of the construction cost (Jacobsen proposed 500,000 from the municipality, 500,000 from the national government, and 250,000 from him). And three, the museum would be built it to Jacobsen's specifications, designed by Vilhelm Dahlerup.

A generous gift—but one that required the public to pick up a big chunk of the tab and forced them to spend their time and energy pursuing an agenda set by Jacobsen. It was also a gift that further burnished the reputation of Jacobsen’s collection (...and thus his personal reputation as a sophisticated patron of the arts).

Thankfully in this case the collection, the building, and the independent institution created to manage both have all stood the test of time—Glyptoteket is a treasure—but once you notice this pattern, repeated across cities worldwide over centuries, it’s inescapable. Some incredibly rich asshole tosses something out there and politicians and the media scamper after it, be it a vaporware technology (Elon fucking musk and the hyperloop), an ill-defined museum on public land, a vanity park, etc. It's the deployment of private wealth as a tool to command public attention, time, and organizational capacity, regardless of popular legitimacy. Still–better a museum of art and antiquities than having a neonazi drop billions of dollars to elect a fascist or a fake giving pledge where these people “donate” their wealth to their fuck-up kids’ ridiculous foundations.

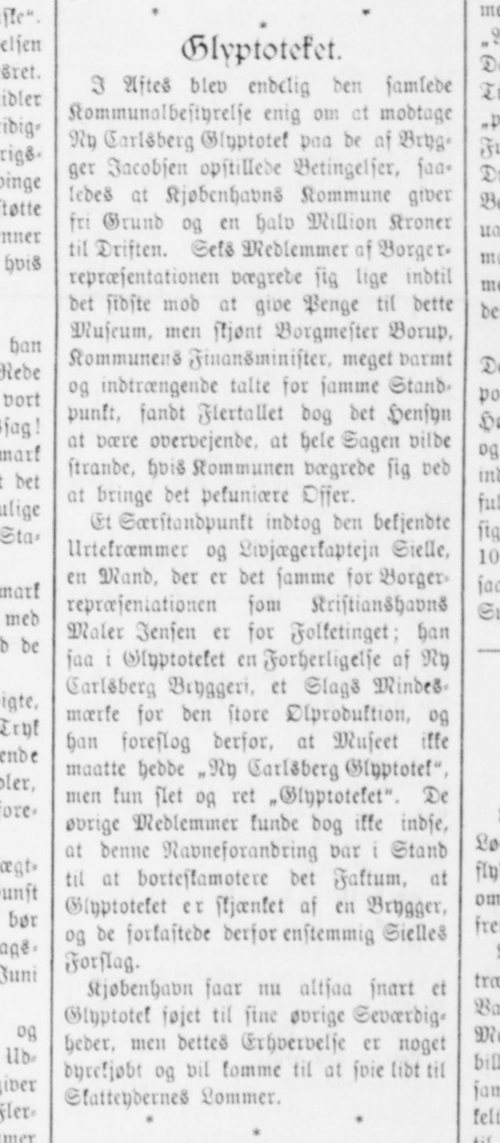

1888 article on Jacobsen's gift in Aftenbladet, Mediestream Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1889 article in Østsjællands Folkeblad on the debate in the city council | 1889 article in København expressing incredulity at the council's delay in voting to build a museum for the gift | 1889 article in København about the council voting to give the land and the money to build Glyptoteket, Mediestream Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1890, illustration of Dahlerup's planned building, Wikimedia Commons

Spurred into action by the size of the potential gift (and the influence of the person making it), the Copenhagen City Council eventually voted in 1889 to give land and 500,000 kroner to house Jacobsen’s collection. It wasn’t a unanimous vote—opponents questioned the generosity of the public contribution, Jacobsen’s motives for the donation, and the perceived moral hazard of naming it for a brewery. A year prior, the Danish parliament had also passed a law of their own committing 500,000 kroner from the national government to support the project.

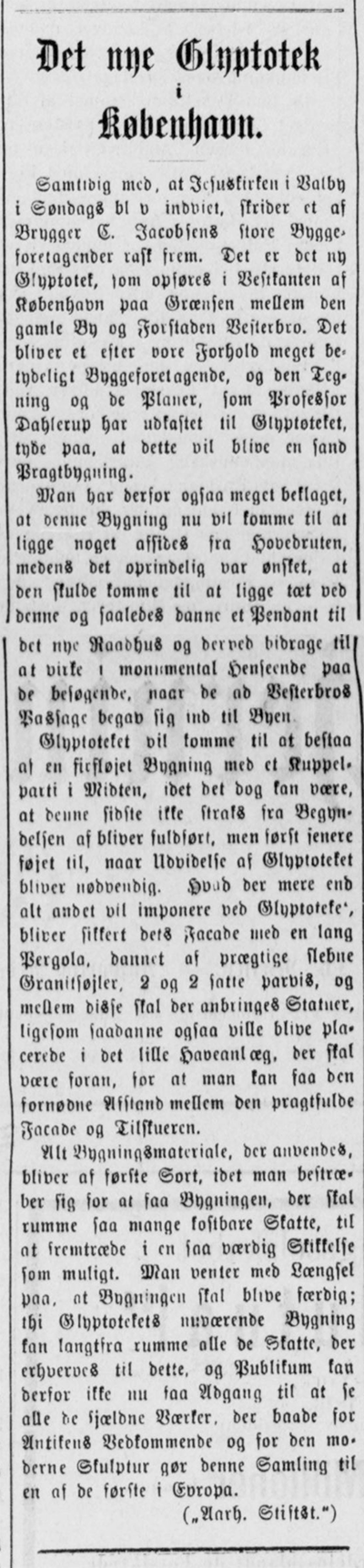

Sites at Ørsteds Parken, Grønttorv, and Højen i Aborreparken were considered, among others, before they settled on a swampy site just outside the old city ramparts across from Tivoli. At the time, the media regretted that the site was “off the main road” of Vestrobros Passage and a ways from the new city hall.

Plans for Glyptoteket at Ørsteds Parken and Grønttorv, Jens Vilhelm Dahlerup's Life and Work | 1898, Peter Elfelt, Mariboes Samling, Københavns Museum

To design it, Jacobsen chose Denmark’s starchitect at the time, Vilhem Dahlerup. One of those architects who was in the right place at the right time, as the rapidly growing city spilled past its old ramparts in the late 1800s, Dahlerup helped define modern Copenhagen, designing the old Royal Theater, Søpavillonen, and Jorcks Passage. Dahlerup was also Carl Jacobsen’s favorite architect, designing a ton of stuff for Carlsberg as the brewery became Denmark’s biggest, including Ny Carlsberg and the Elephant Gate—it's obvious who picked him to design Glyptoteket (Jacobsen was already asking Dahlerup to sketch some ideas for Glyptoteket all the way back in 1884).

1740 Bernardo Bellotto painting, The Rio dei Mendicanti and the Scuola di San Marco, Wikimedia Commons | 2017 photo Scuola di San Marco, Wikimedia Commons | Glyptoteket in 2012, Ole Haupt, Wikimedia Commons | Statens Museum for Kunst in 2016, Jiří Komárek, Wikimedia Commons

Dahlerup was the Danish king of architectural historicism, and here he modeled his design on the Scuola Grande di San Marco in Venice, which was then the Italian city’s hospital. He was also working on the Statens Museum for Kunst, the national art museum, at roughly the same time, and you can absolutely spot similarities between the two.

Dahlerup’s plans for Glyptoteket included a lavish dome from the beginning, but it was initially abandoned for cost reasons, which also scuppered plans to face the sides with granite and limestone rather than brick.

Cupola sketch and floorplan, Jens Vilhelm Dahlerup's Life and Work | 1903 article on the dome being built in Social-Demokraten, Mediestream, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1904, Frederik Riise, the Museum of Copenhagen | 2017, Erik Nicolaisen Høy, Københavns Stadsarkiv via the Museum of Copenhagen

The New Carlsberg Glyptotek opened in May 1897 with an exhibition of international art, before Jacobsen’s collection moved over from his estate in Valby.

Dahlerup’s building and original site plan anticipated future expansion. With Glyptoteket an immediate hit upon opening, gears swiftly began turning on an addition. In particular, Carl Jacobsen really, really wanted to make the dome happen. Constructed between 1903 and 1906, architect Hack Kampmann ended up designing the addition, but Dahlerup came back to complete Jacobsen’s dome—in ironwork and glass this time, creating Glyptoteket’s delightful winter garden. The switch in architects gives Glyptoteket kind of a reverse mullet effect—Dahlerup’s festive Venetian party in front with Kampmann’s foreboding business in the back.

1897 article on the opening of Glyptoteket, Kjøbenhavns Amt Avis | 1897 photo, Mariboes Samling, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1906 grand opening article in Berlingske, Mediestream, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | ~1906 photo, Fritz Theodor Benzen, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1906 photo, Fritz Theodor Benzen, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1909 photo, Ernst Nyrop Larsen, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1914 site plan, Københavns Stadsarkivs via the Museum of Copenhagen | 1924 postmarked postcard, Wikimedia Commons

While it may have been a less visible thoroughfare in the 1890s–when Vestre Boulevard was only a few decades removed from serving as a moat protecting Copenhagen’s western walls—today H.C. Andersens Boulevard is an eight-lane proto-highway slicing past Glyptoteket and through the heart of Copenhagen.

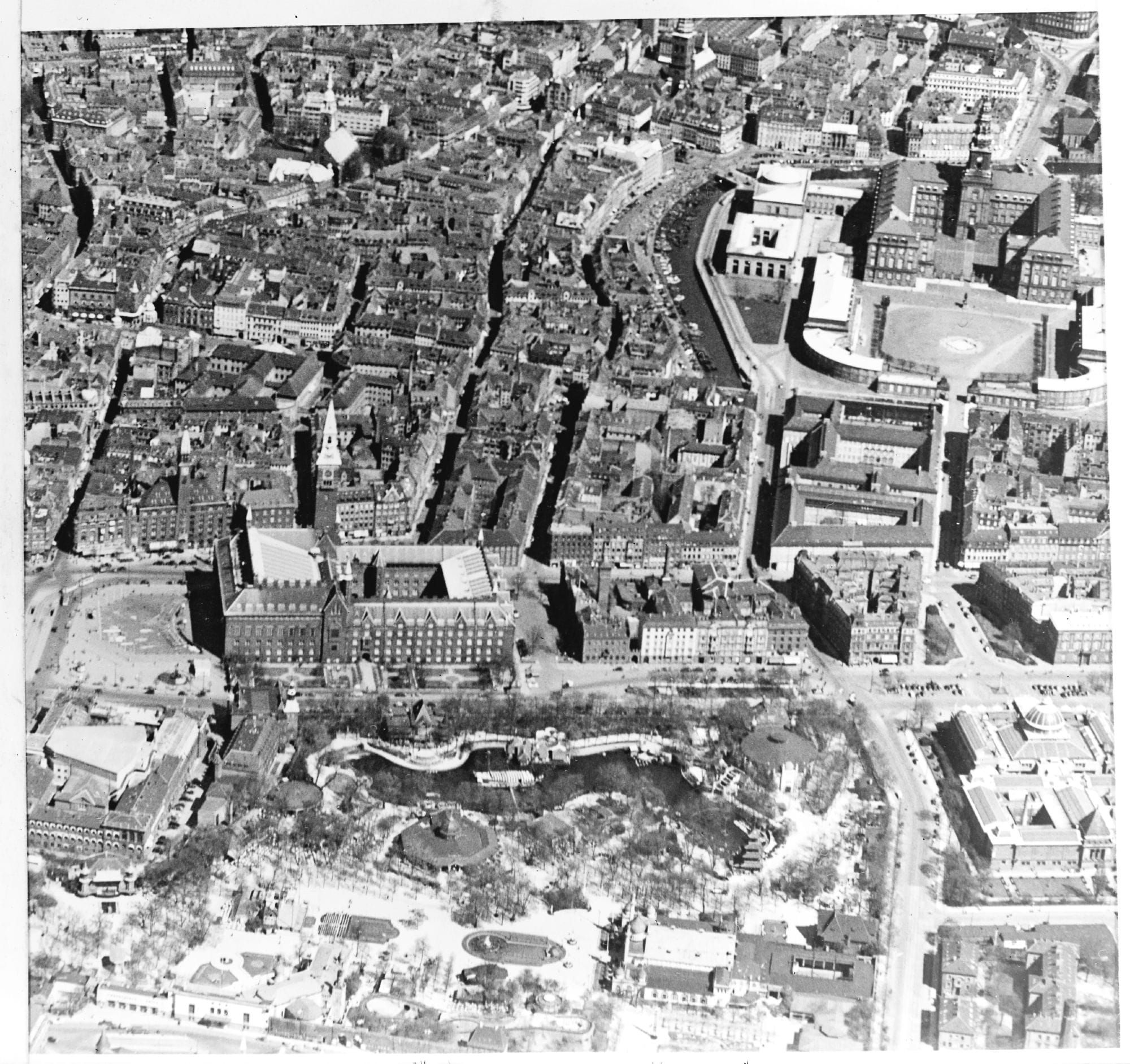

It’s also a good reminder that even places like Denmark fucked up their cities in the 1950s and 1960s. The government expanded H.C. Andersens Boulevard in 1954-1955 and now it’s the most highly trafficked normal street in the entire country.

Undated, Paul Fischer, the Museum of Copenhagen | Late 1920s-early 1930s aerial, Danmark Set Fra Luften, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Fritz Theodor Benzen, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1954, widening of H.C. Andersens Boulevard, Mogens Falk-Sørensen, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1960s aerial, Danmark Set Fra Luften, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1990s aerial, Danmark Set Fra Luften, Det Kgl. Bibliotek

…and yet, even with the extra car lanes, at rush hour more than 2.5x as many cyclists use it as cars.

The block of H.C. Andersens Boulevard in front of Glyptoteket—a grassy median, trees, and a sculptural column dedicated to Dante—is the only stretch of the street that hints at how it looked before the 1950s widening. Featuring ultra-wide sidewalks, lined with sculpture, and thick with shade trees, it was healthier, quieter, and more sustainable than its current traffic-choked, polluted state.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Glyptotekets Arkitektur (2023)

- Carl Jacobsen's letters about Glyptoteket, New Carlsberg Foundation Archive

- The conservation listing from the Kulturstyrelsen

- Jens Vilhelm Dahlerup's Life and Work

- In Arkitekten: Månedshæfte in 1906

Some more articles from the 1880s, 1890s, and 1900s about the political maneuvering to get the government to chip in, the building inaugurations in 1897 and 1906, and some architectural criticism from 1897.

There were briefly two Glyptoteket's–the one at Jacobsen's villa in Valby and this one. This one opened with an international art exhibition in 1897, and Jacobsen's collection was only moved in afterwards (Denmark was big on the swastika around the turn of the century, long before the Nazis ruined it).

1897 ad for the inaugural exhibition, Mediestream, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1898 ad for the two Glyptoteks, Mediestream, Det Kgl. Bibliotek

1954, Mogens Falk-Sørensen, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1955, Mogens Falk-Sørensen, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1960, Mogens Falk-Sørensen, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1966, Wikimedia Commons

Member discussion: