It only took a cataclysmic earthquake, a catastrophic fire, and a sensational murder on the other side of the country for a woman to get the commission for San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel. Julia Morgan, the first woman licensed as an architect in California, turned the charred shell of the Reid Brothers’ original Fairmont into a functional hotel after the nearly-complete building burned during the 1906 earthquake–but only after the first architect tapped for the rebuild, Stanford White, was shot dead during a musical theater performance at Madison Square Garden in New York.

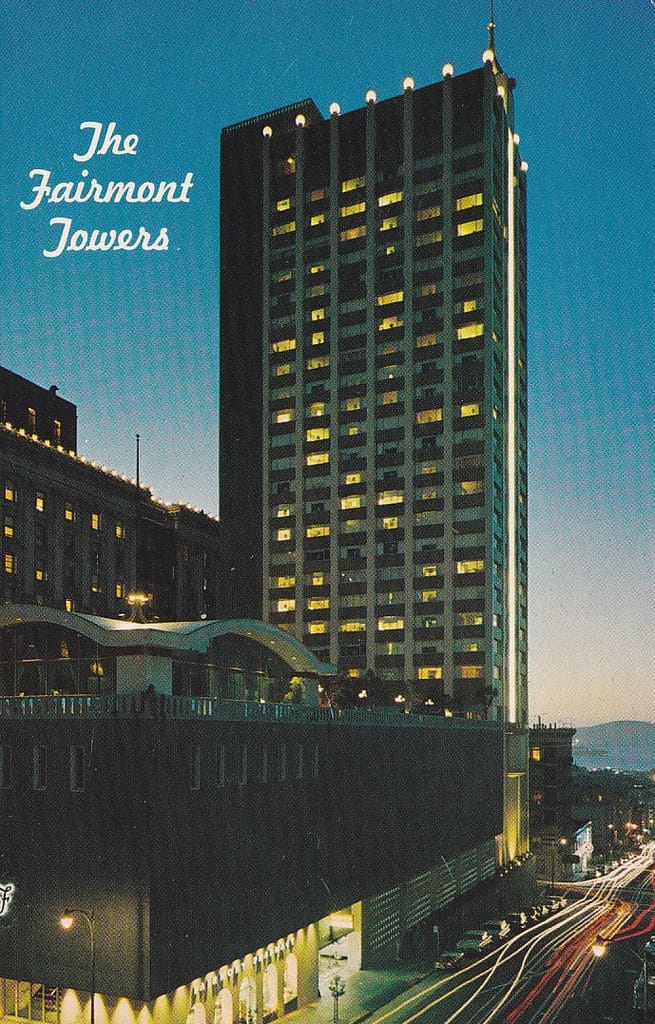

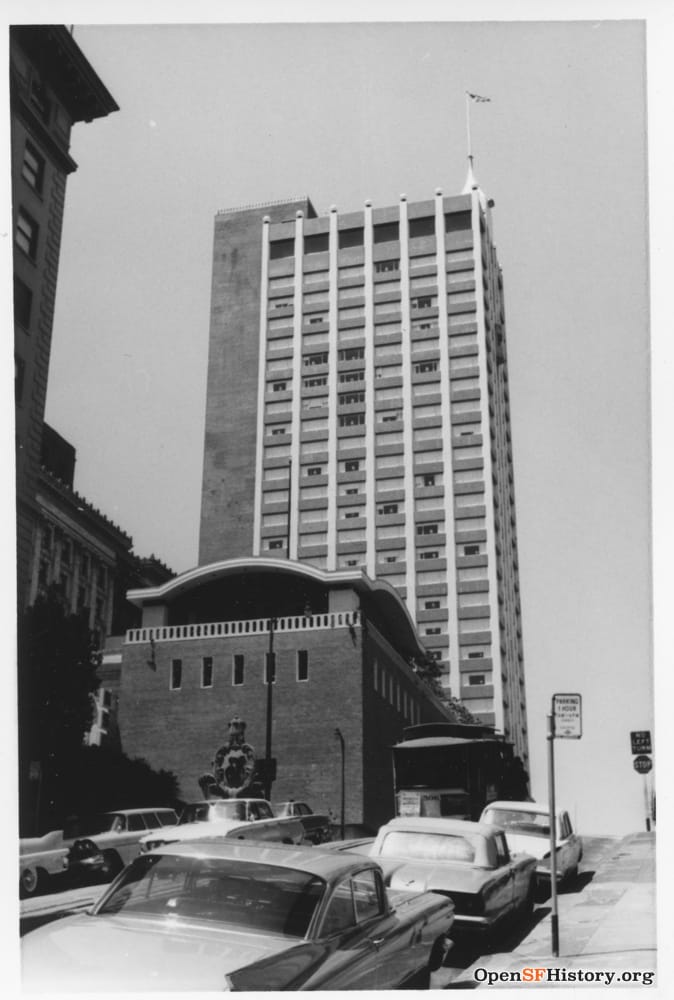

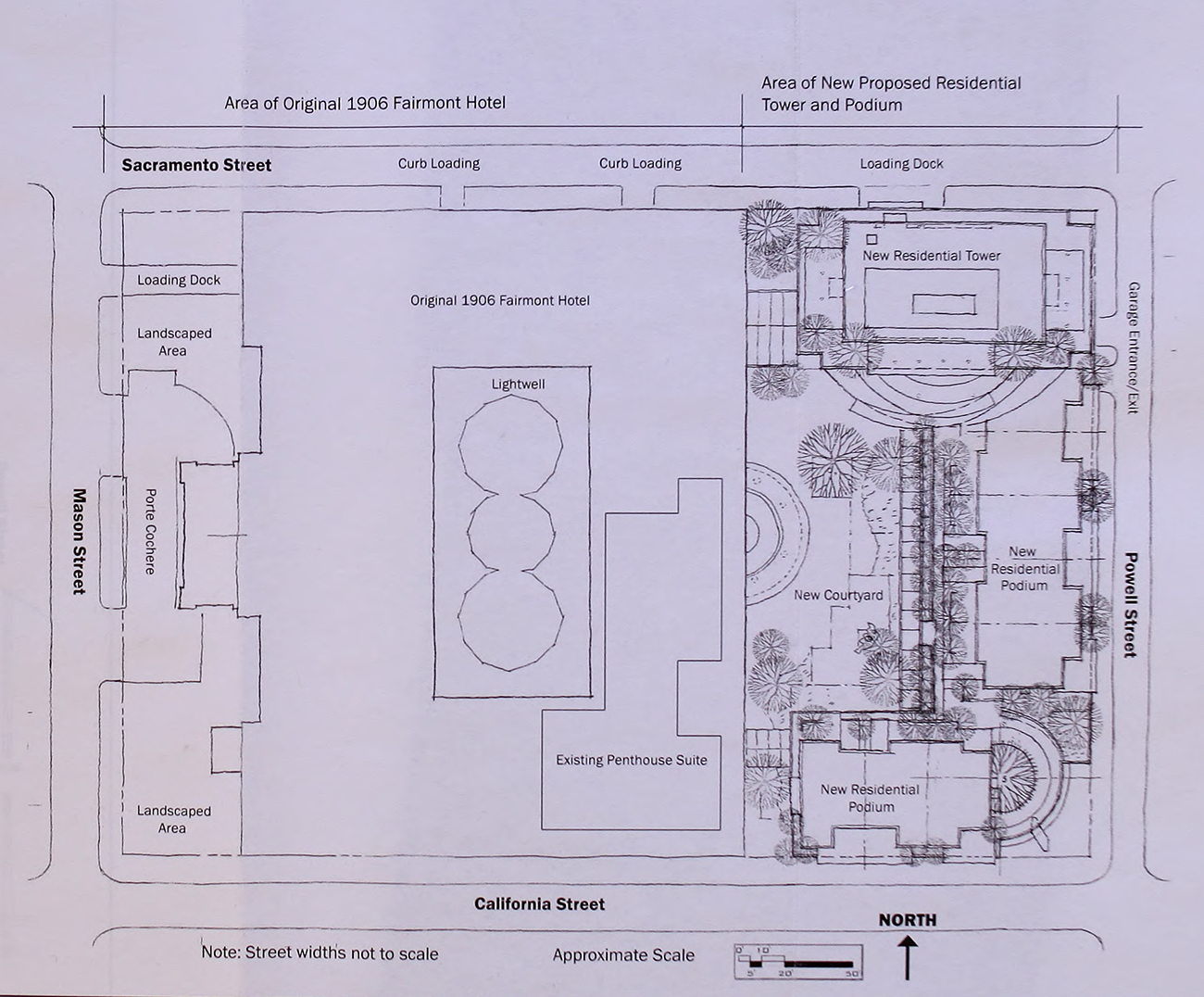

A clumsy addition designed by Mario Gaidano added event space to this corner, a Lawrence Halprin-designed rooftop garden, and a 29-story hotel tower (with a neat illuminated glass elevator). San Francisco’s utterly broken planning processes killed an early 2010s plan to demolish the addition and replace it with a similarly-sized condo tower. This might be one of the few times the city’s sclerotic building policies worked out alright–it seems crazy to me to demolish a hotel tower and waste all that embodied carbon to build an…identically-sized condo tower. Just figure out a way to adaptively reuse the hotel, and build those condos literally anywhere else in the city–give me six five-story buildings in Outer Sunset, Richmond, Noe Valley, etc. instead (...really, give me thousands of them, all over).

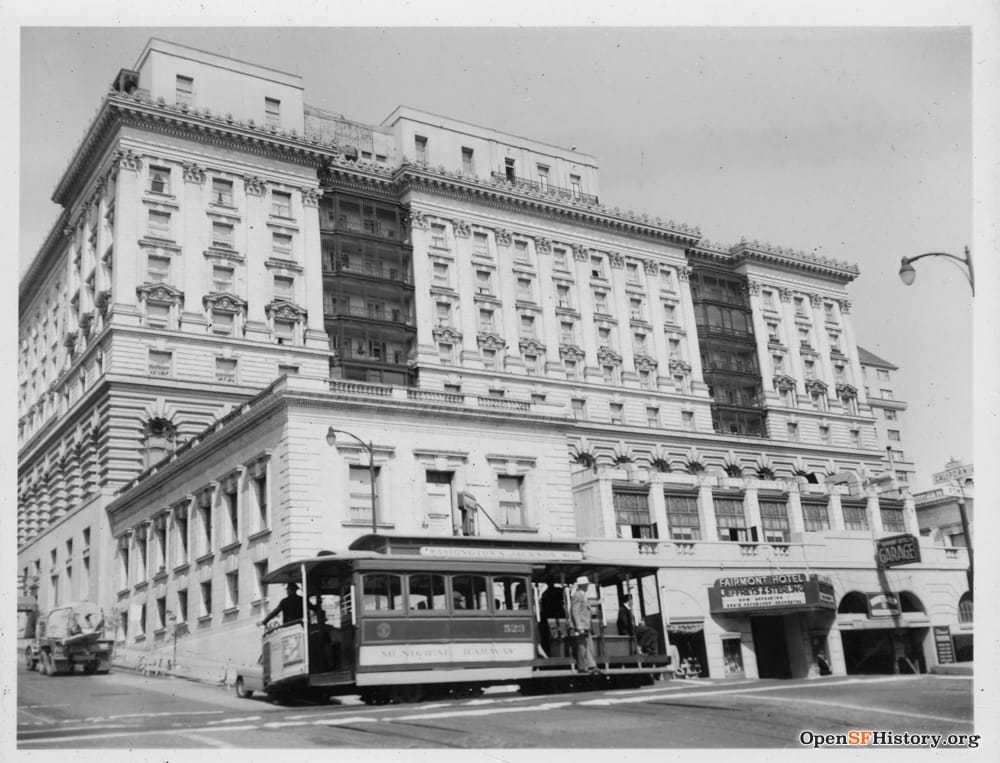

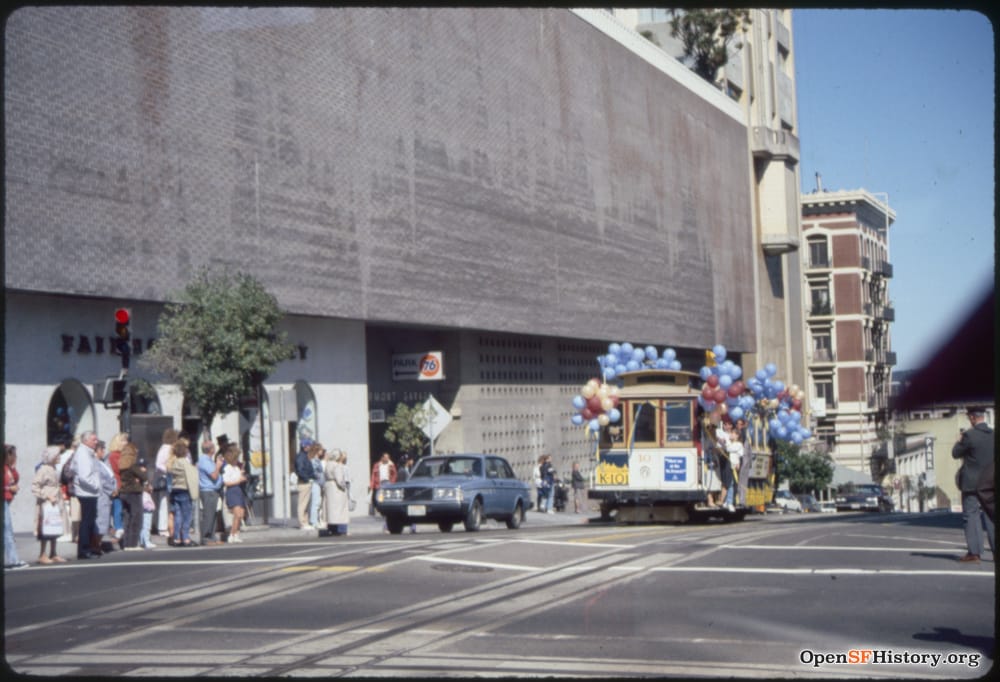

So what’s changed? There’s the incredibly obvious (the conference center plopped onto the corner of California and Powell), the subtle (a 1927 addition added an extra floor and a penthouse on top of the original hotel), and the minute (street trees!). Taken as a whole, though, it basically looks like exactly what it is: a pompous Beaux Arts hotel with a clunky-but-harmless modernist appendage sprouting out of it–neither are really to my taste, tbh.

Heiresses Theresa Fair Oelrichs and Virginia Fair Vanderbilt, the developers of the Fairmont, named the hotel for their dad, James G. Fair, an Irish immigrant turned ‘Silver King’ after striking it rich at the Comstock Lode in Nevada. However, the Fair daughters were not the ones who hired Julia Morgan to work on their hotel–this wasn’t a tale of women supporting women. The Fair sisters hired the Reid brothers to design the hotel. Influential in San Francisco around the turn of the century, Reid & Reid did theaters, department stores, classical revival mansions, the San Francisco Call office building, and–maybe most notable today–the Hotel del Coronado in San Diego.

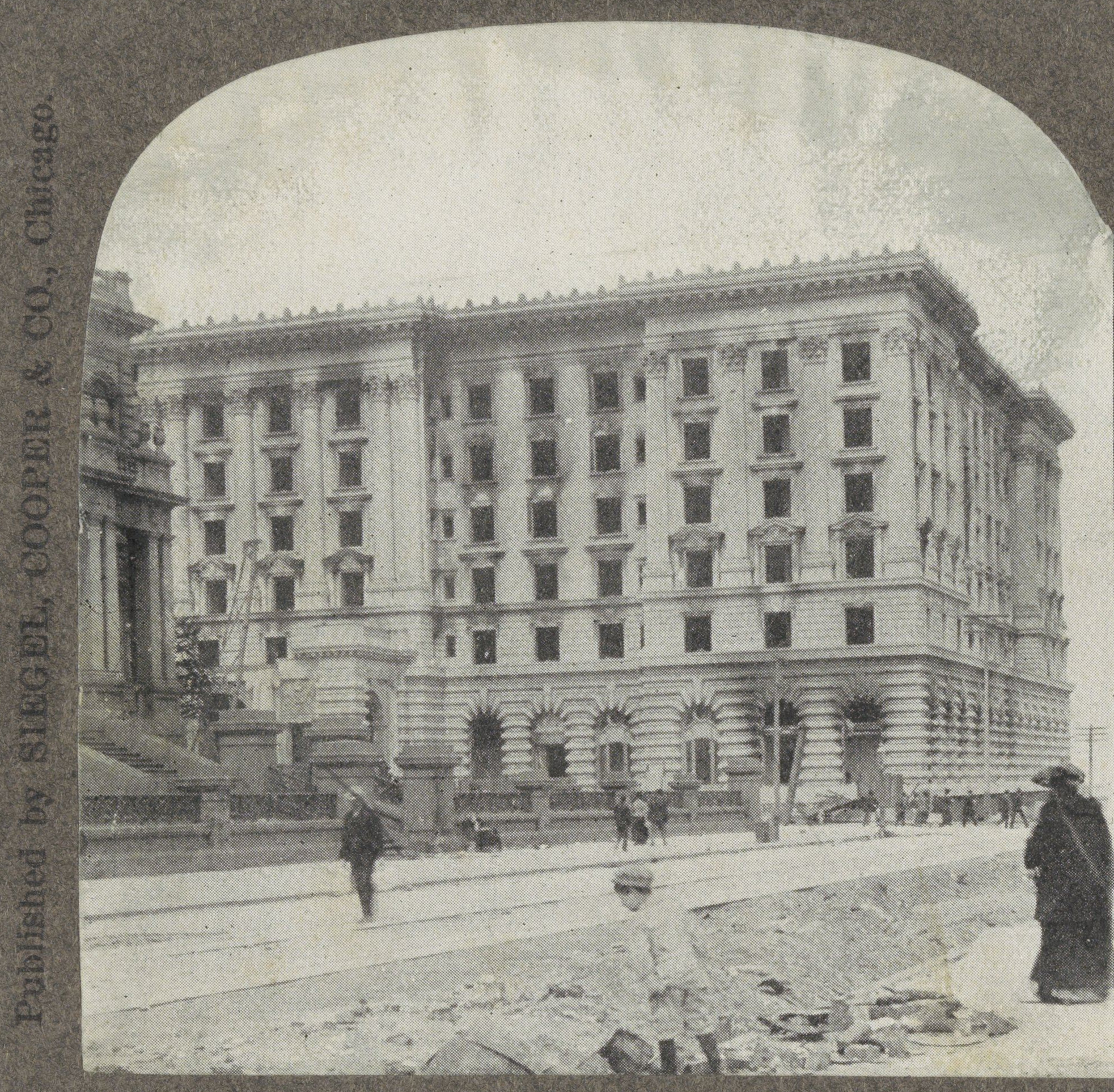

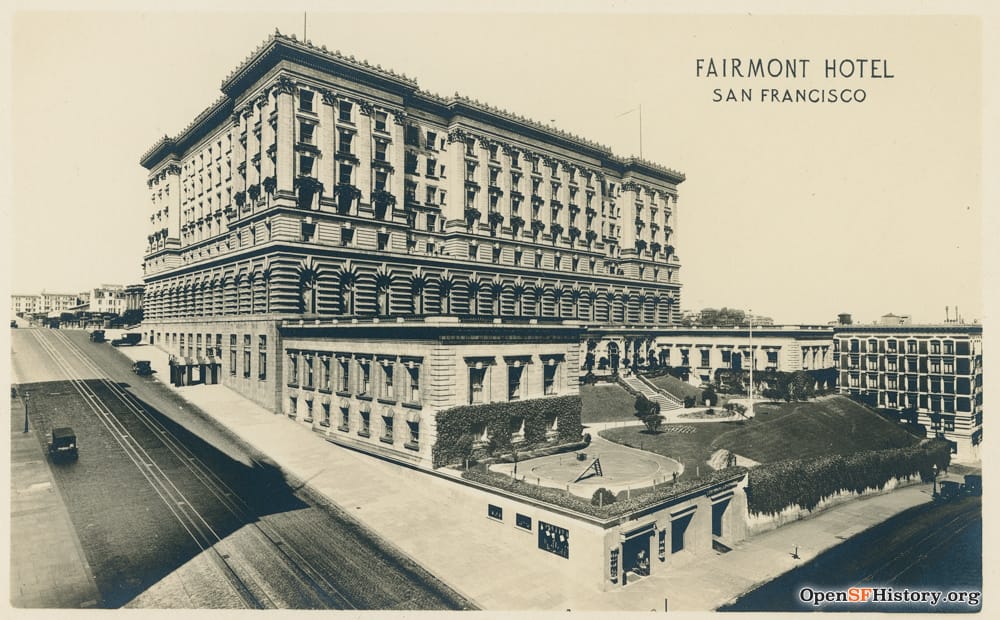

The Reids designed the Fairmont in a monumental Beaux Arts style, an opulent hilltop hotel that aspired to be San Francisco’s finest. With the building nearly complete, the Fair sisters cashed out and sold the hotel to Herbert and Harland Law on April 6th, 1906.

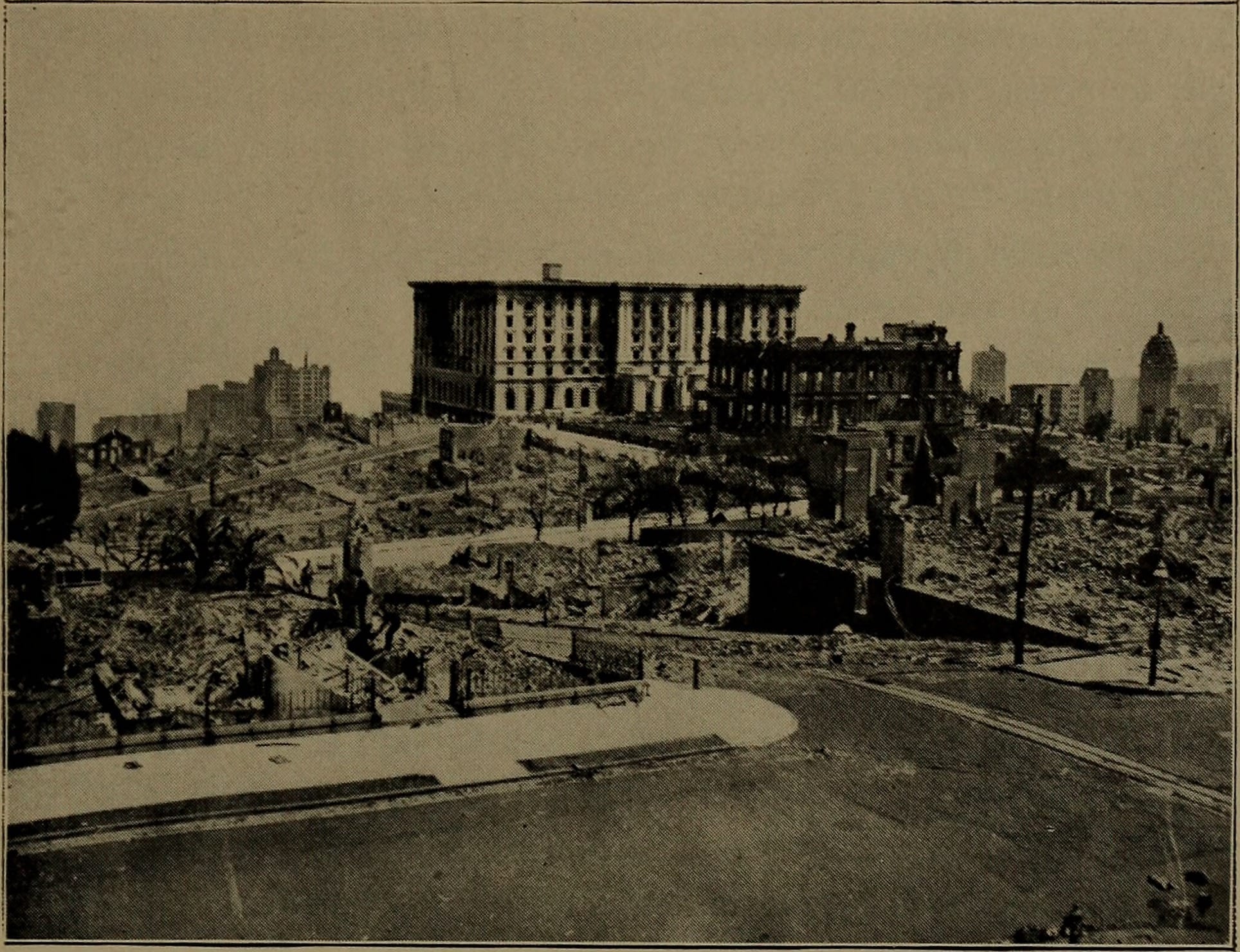

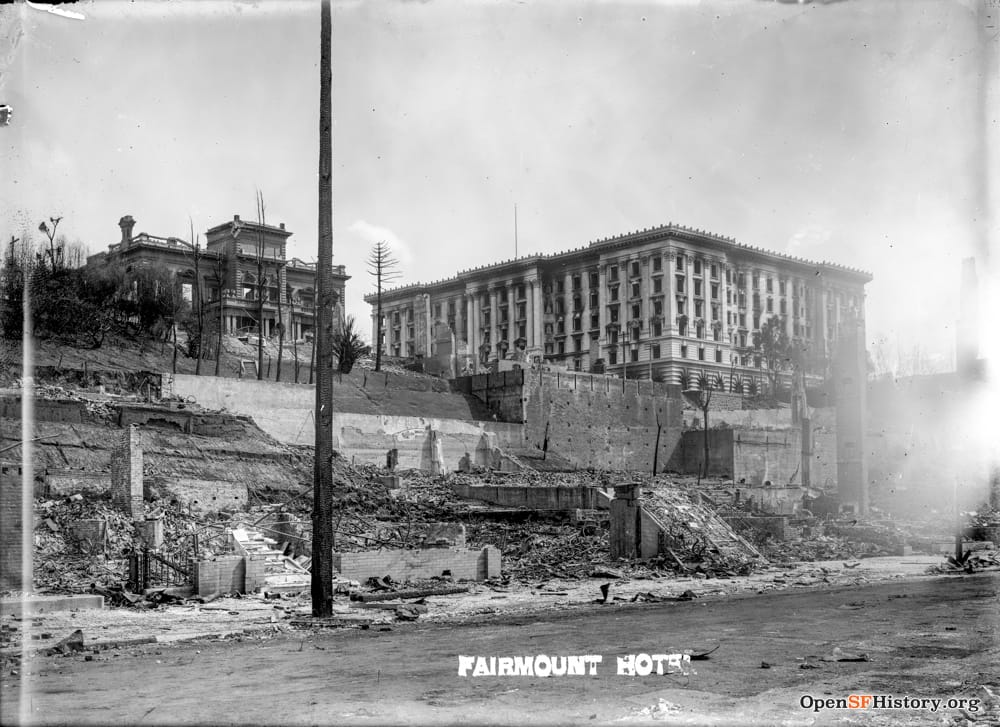

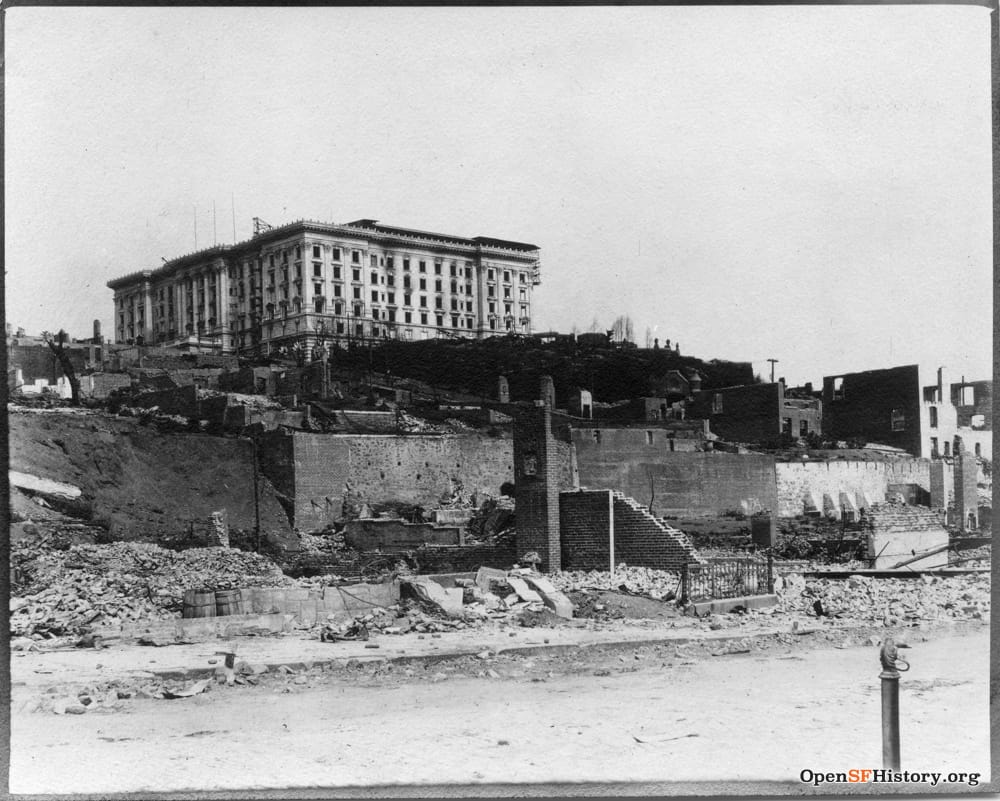

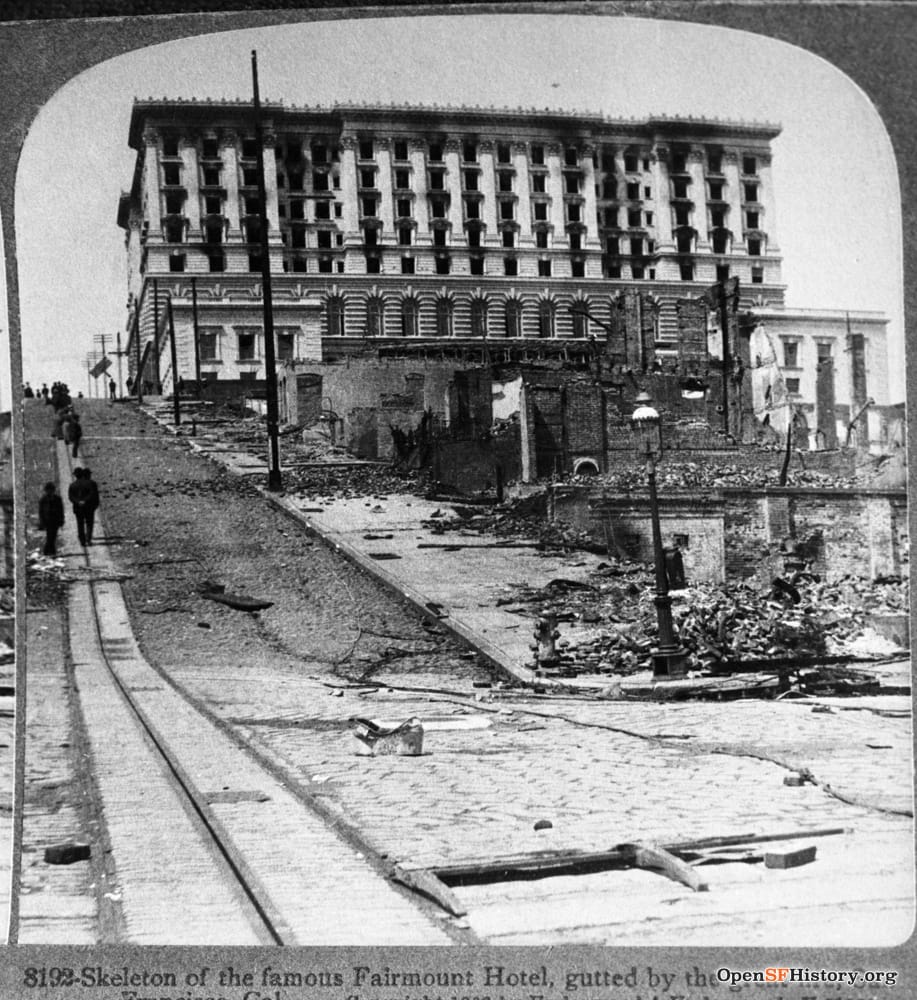

1906, after the earthquake looking east on California, Wikimedia Commons | 1906, after the earthquake looking east, Wikimedia Commons | 1906, Fairmont in background, H.D. Chadwick, Wikimedia Commons | 1906 with a mailbox, OpenSFHistory / wnp27.0072 | 1906 with the two survivors on Nob Hill, OpenSFHistory / wnp15.1032 | 1906 with ruins, H.C. White, OpenSFHistory / wnp24.0092a | 1906, OpenSFHistory / wnp27.0209 | 1906 looking west, Marilyn Blaisdell Collection, OpenSFHistory / wnp70.10097 |

…twelve days later, on April 18th, a 7.9 magnitude earthquake leveled San Francisco, and the ensuing fires destroyed just about anything that was left. The fires gutted the almost-finished Fairmont and damaged its shell, but it was one of two buildings on Nob Hill to (mostly) survive.

To rebuild the hotel, the Laws commissioned Stanford White, namesake partner in New York’s prestigious firm of McKim, Mead & White and the architect of grand Gilded Age mansions on the East Coast. White was also a sexual predator, even by the standards of the powerful men of the time–he used his influence, money, and connections in the arts to groom young girls. In one of the most dramatic murders in American history, only two weeks after White was hired to work on the Fairmont, the husband of one of White’s victims shot and killed him during a performance at Madison Square Garden’s rooftop theater (a venue that White had himself designed). There were no good guys here–White’s killer, Harry Kendall Thaw, sounds like a spoiled, violent loon whose family money bought him impunity and power as well.

Skeleton of the 'famous Fairmont', 1906, Underwood & Underwood, Marilyn Blaisdell Collection, OpenSFHistory / wnp37.01063 | 1906, R.J. Waters & Co., OpenSFHistory / wnp13.046 | 1908, OpenSFHistory / wnp15.1705 | 1915, Pillsbury Picture Co., Zelinsky Collection, OpenSFHistory / wnp59.00122

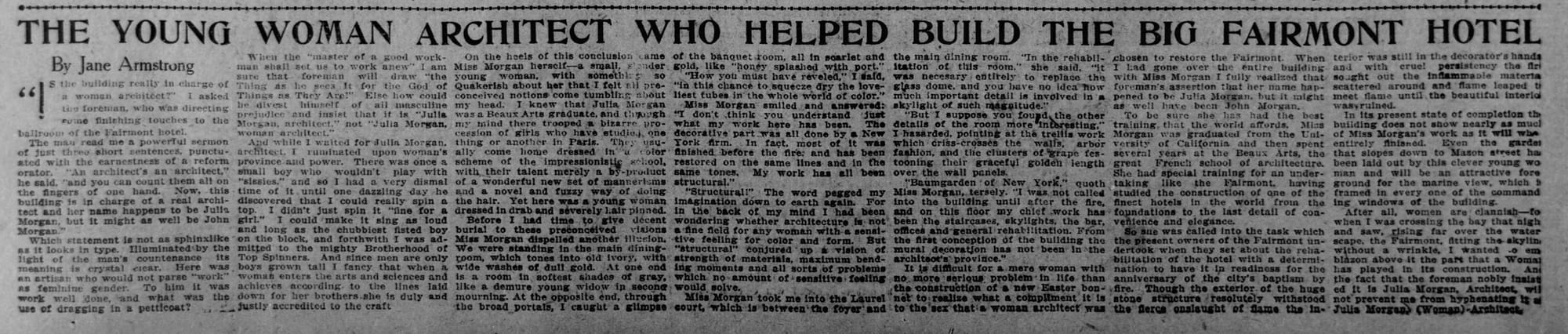

In less than three months the Fairmont had been bought, hit by an earthquake, gutted by fire, and had its handpicked architect murdered–this deal was clearly cursed. Only after all that did the new owners turn to Julia Morgan, the first woman licensed as an architect in California, who told them the damaged shell of the hotel could be salvaged. El Campanil, a reinforced-concrete bell tower that Morgan built at Mills College, survived the earthquake, proving Morgan’s engineering chops and helping her nab the Fairmont rebuild. Subverting lazy gender stereotypes, Julia Morgan was an expert engineer and a pioneering user of reinforced concrete.

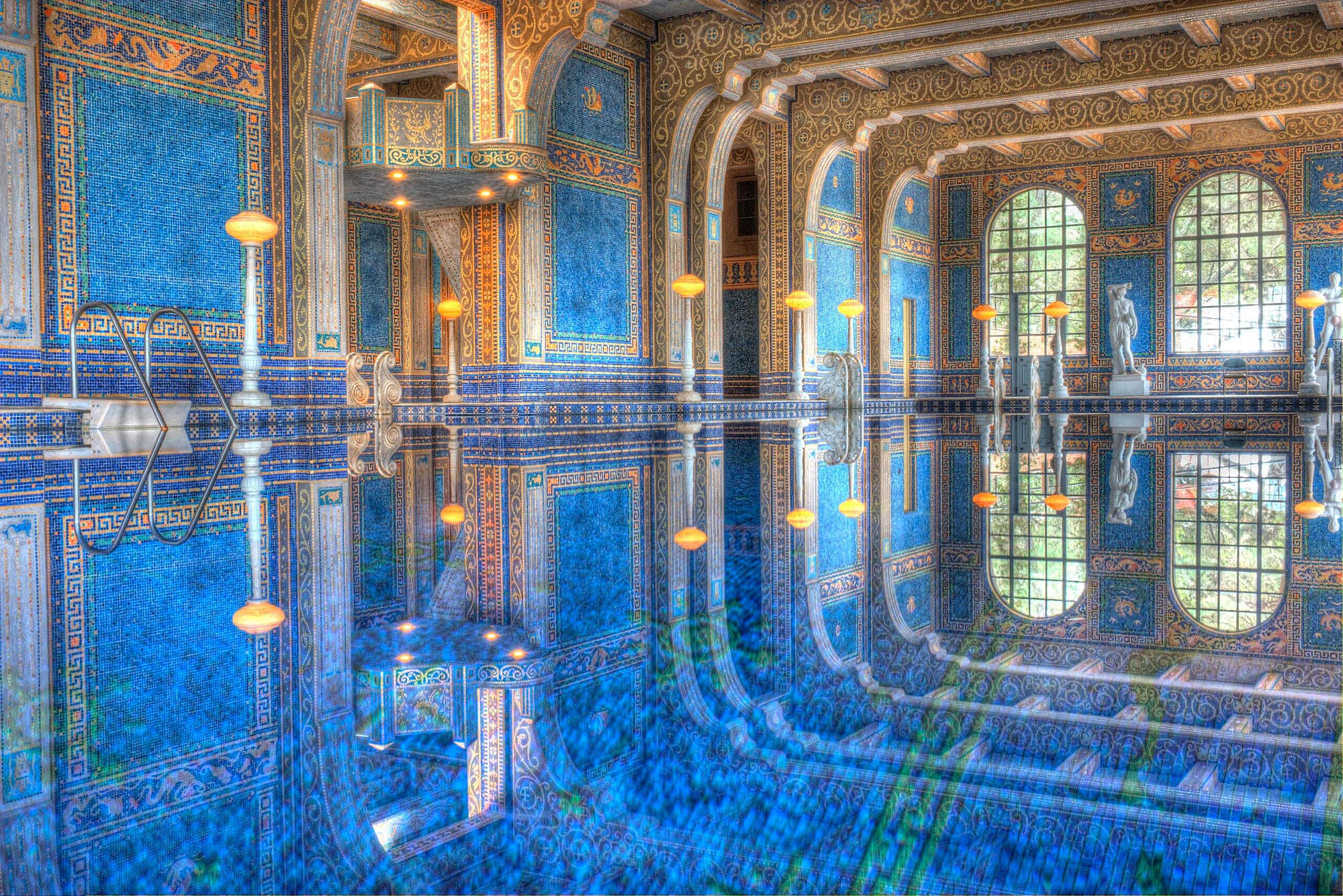

Coming only two years after she earned her license, Morgan’s structural and interior work on Fairmont helped launch her career. She would go on to become one of the most productive and influential architects in California history. Her firm designing more than 700 buildings over her long career, including–most famously–Hearst Castle.

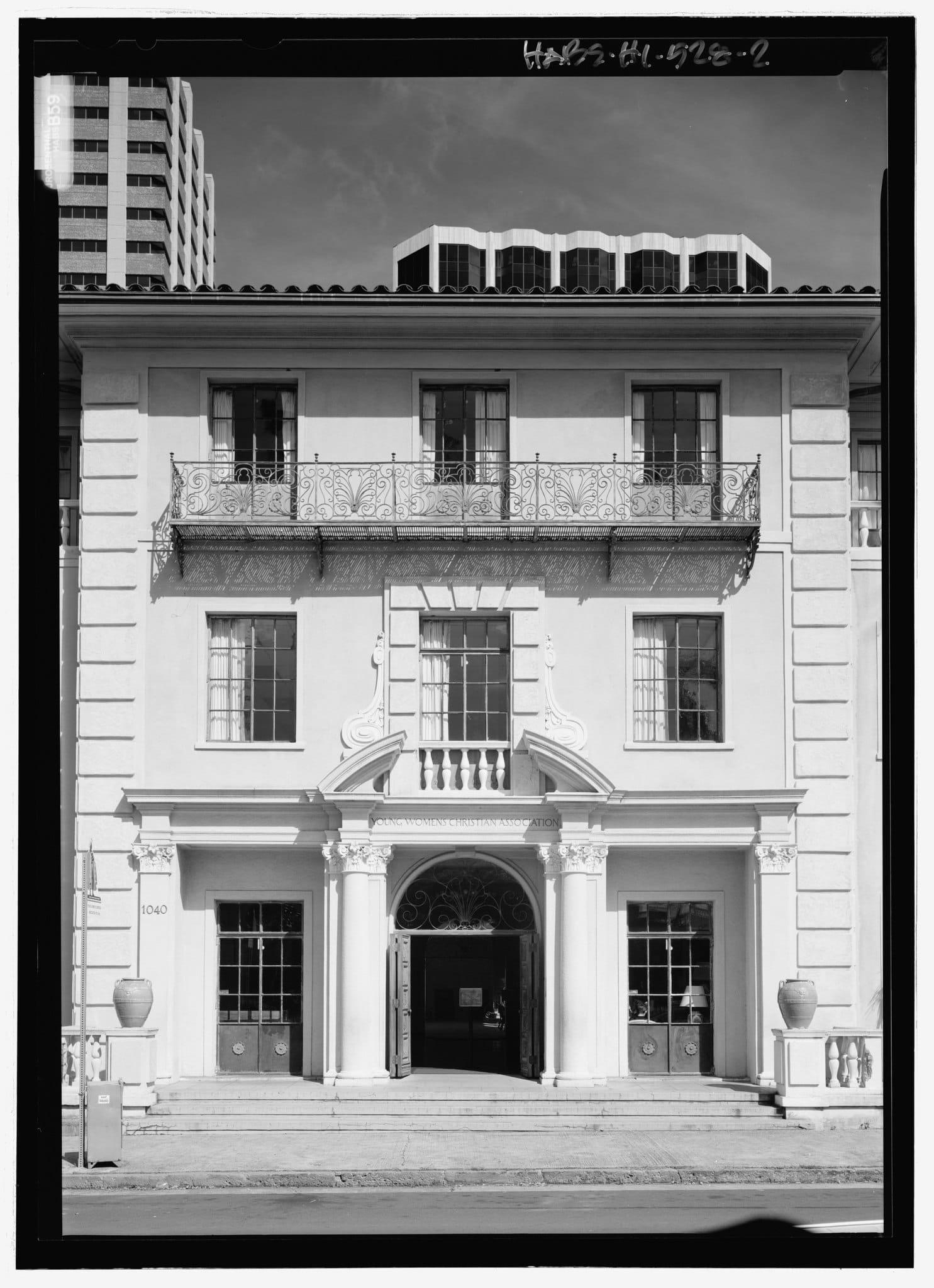

Julia Morgan in 1918, Cal Poly Library | the Julia Morgan-designed YWCA of Honolulu, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons | Hearst Castle Roman Pool, designed by Julia Morgan, Wikimedia Commons | Heart Castle Casa Grande, Wikimedia Commons

The rebuilt Fairmont Hotel finally opened in 1907, kicking off a long reign as one of the most lavish hotels in the city–the Fairmont has historically been the hotel of presidents in San Francisco. When it opened, it also served as a residential hotel–half the rooms were reserved for permanent guests who wanted a downtown pied-à-terre. A 1927 addition added an extra floor on top as well as a penthouse. The UN Charter was mostly drafted in that penthouse, as it served as Secretary of State Edward Stettinius’ apartment and office during the United Nations Conference on International Organization in 1945 (the conference that founded the UN).

1925, Marilyn Blaisdell Collection, OpenSFHistory / wnp70.1222 | 1935, Zan Stark, Marilyn Blaisdell Collection, OpenSFHistory / wnp70.1224

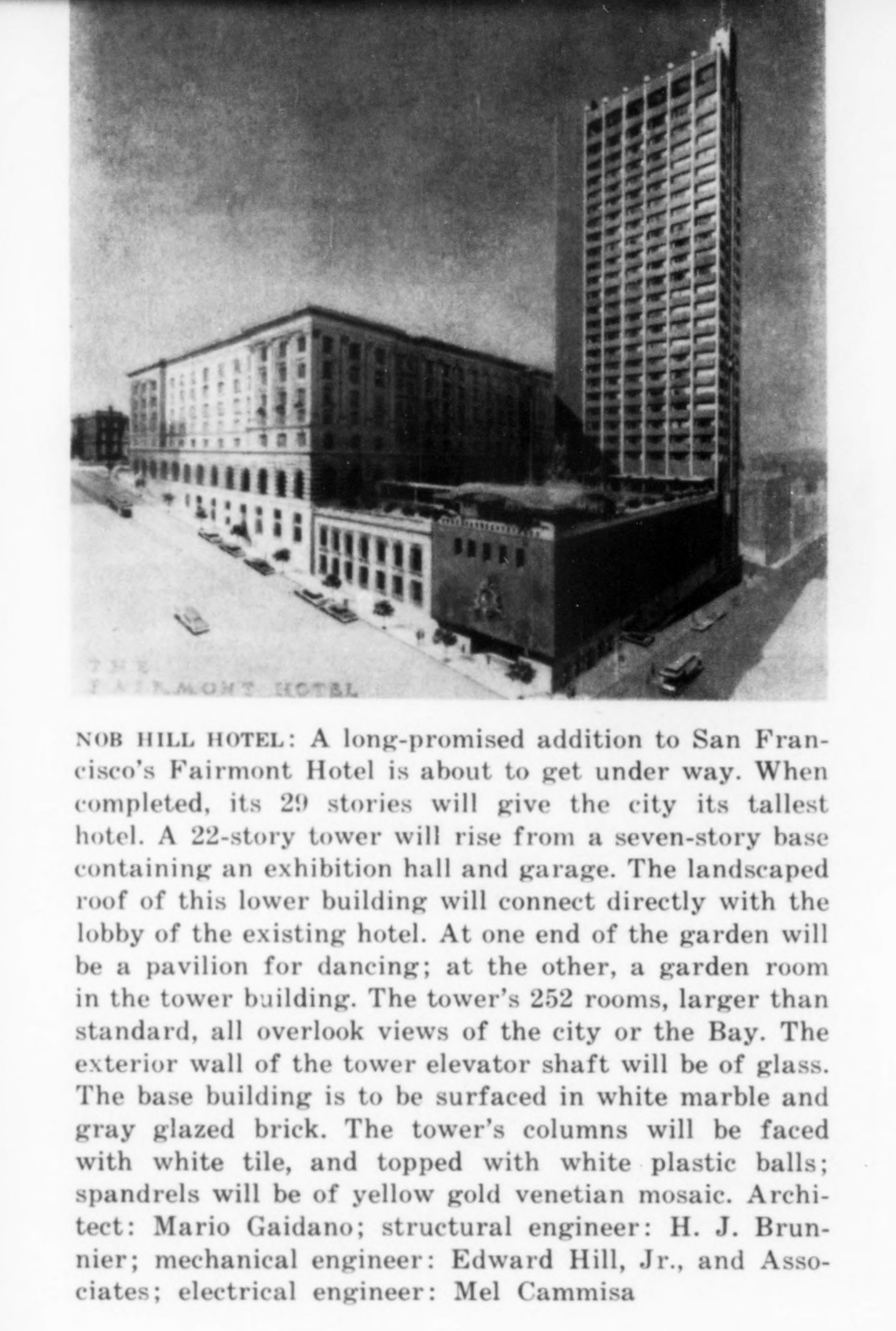

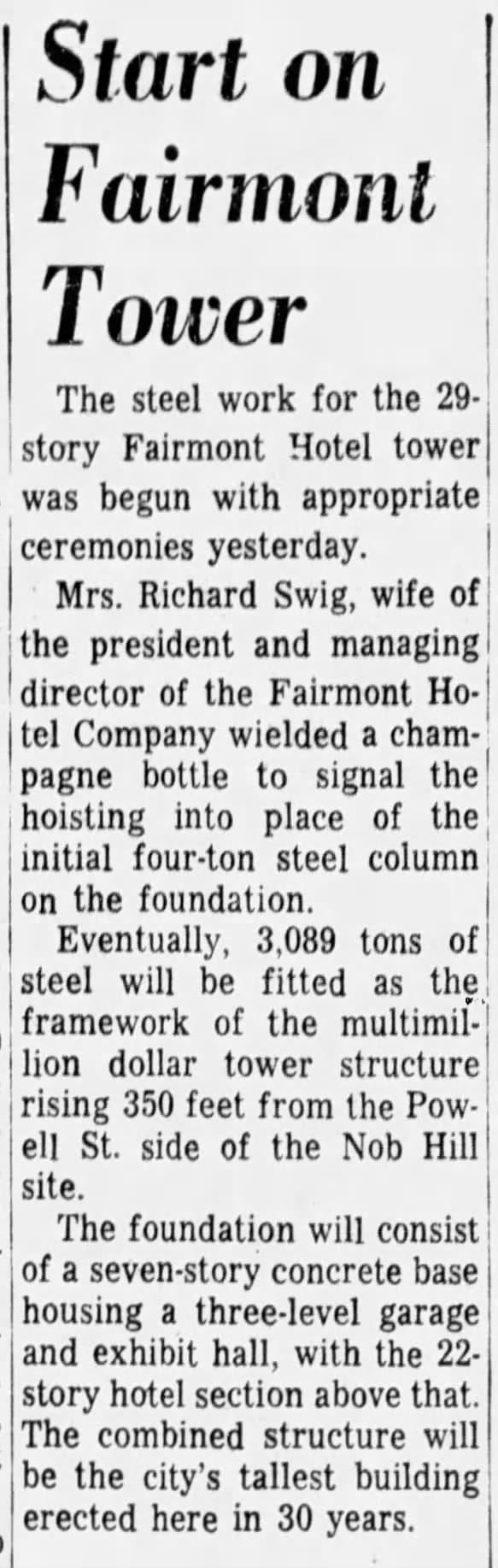

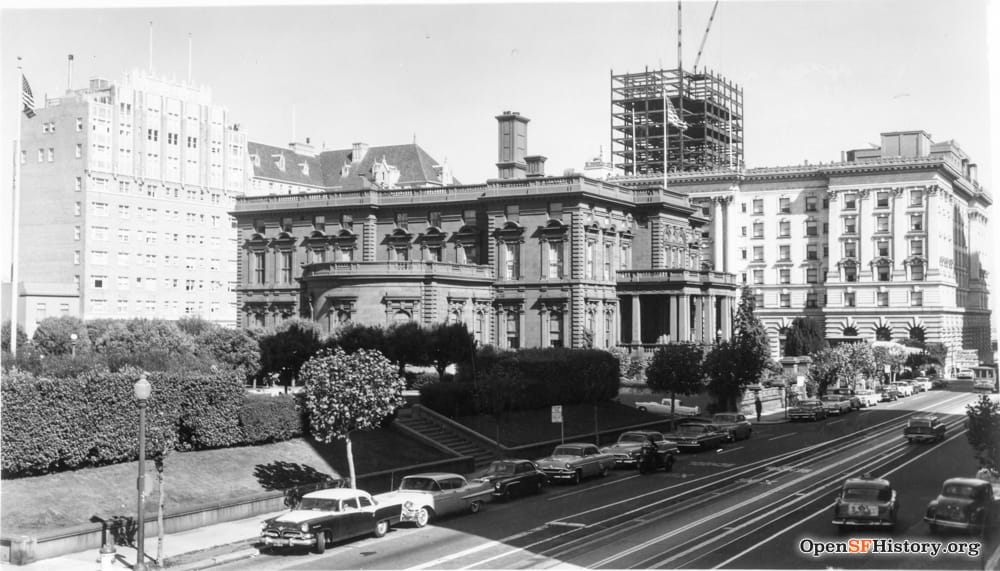

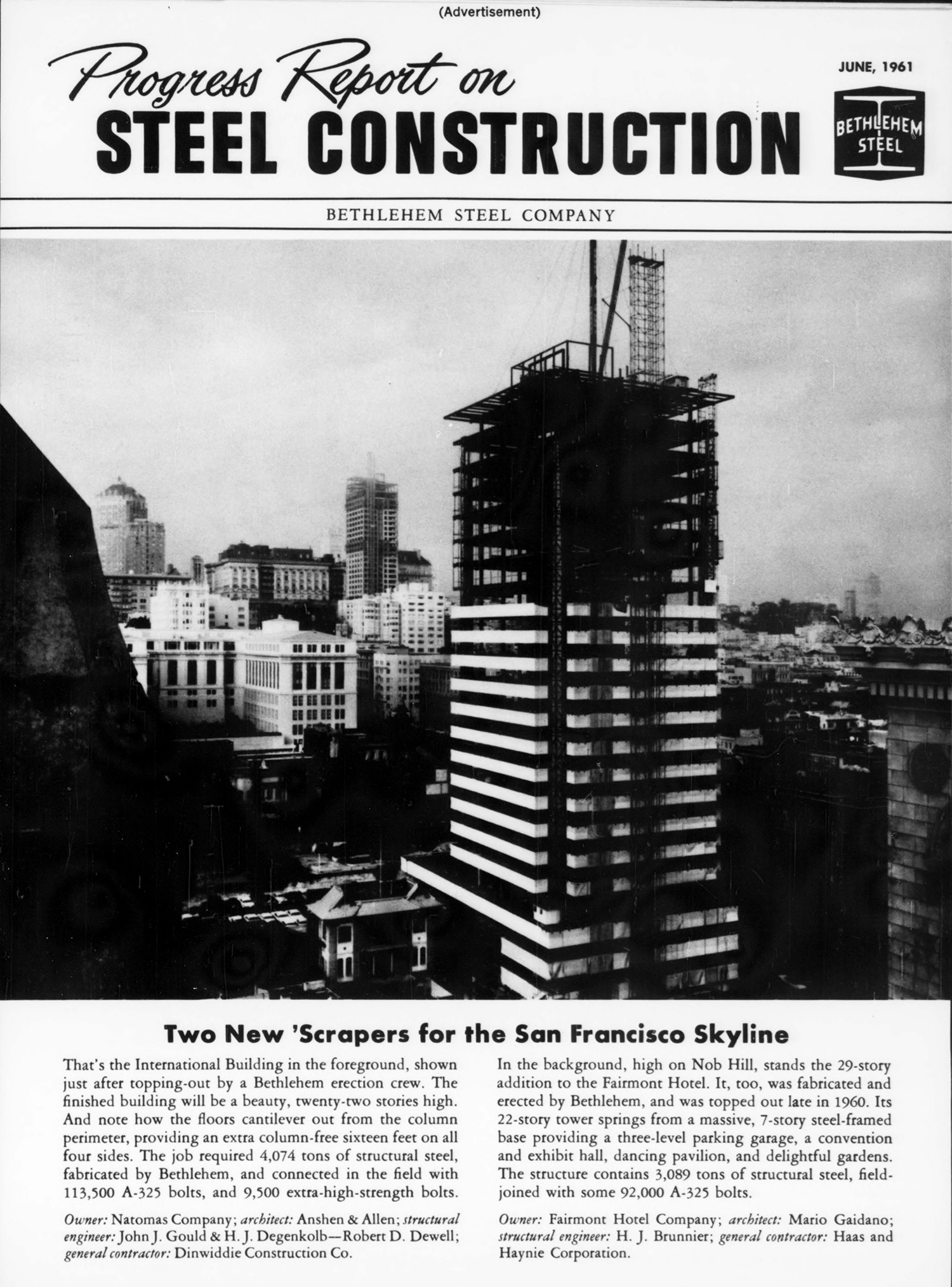

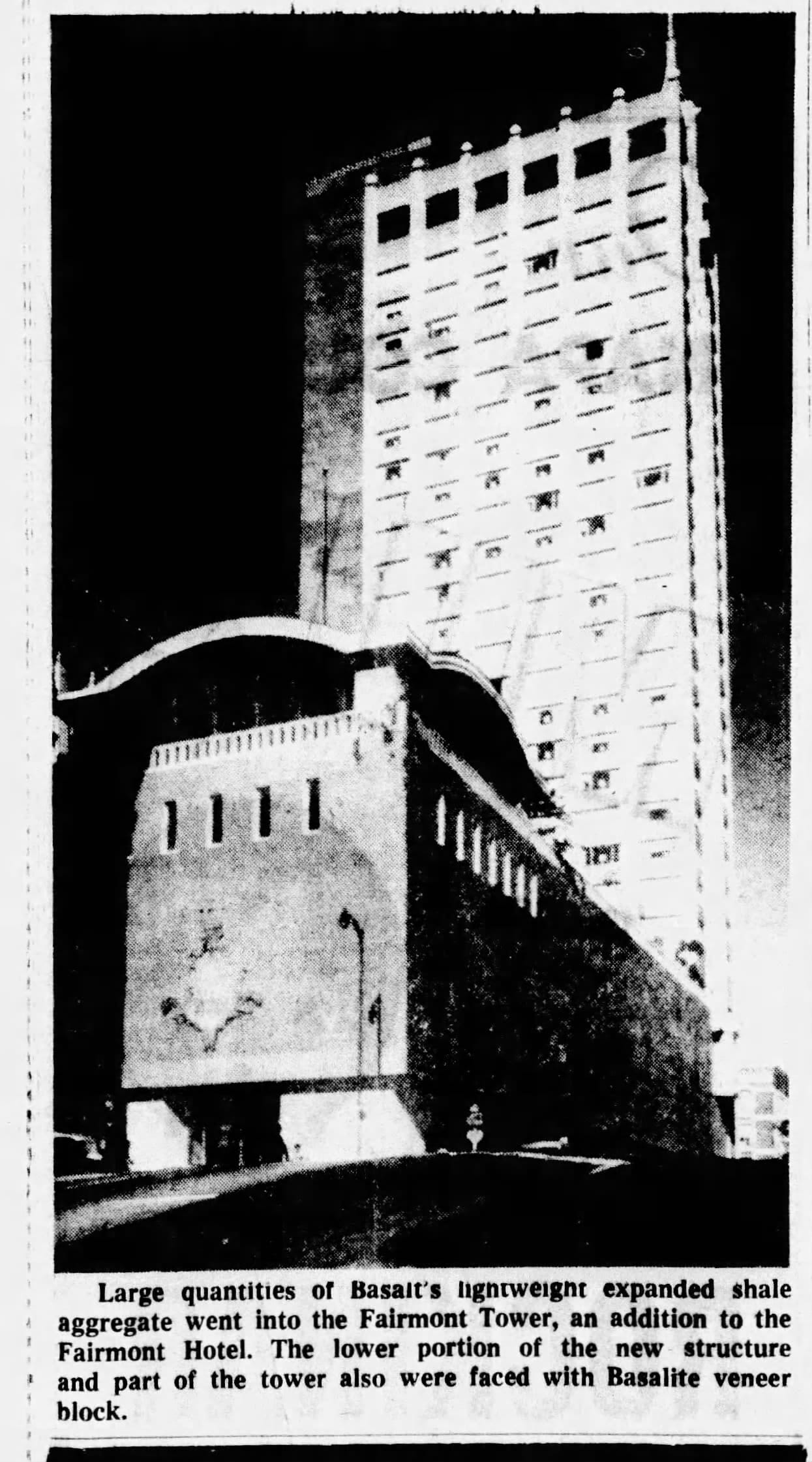

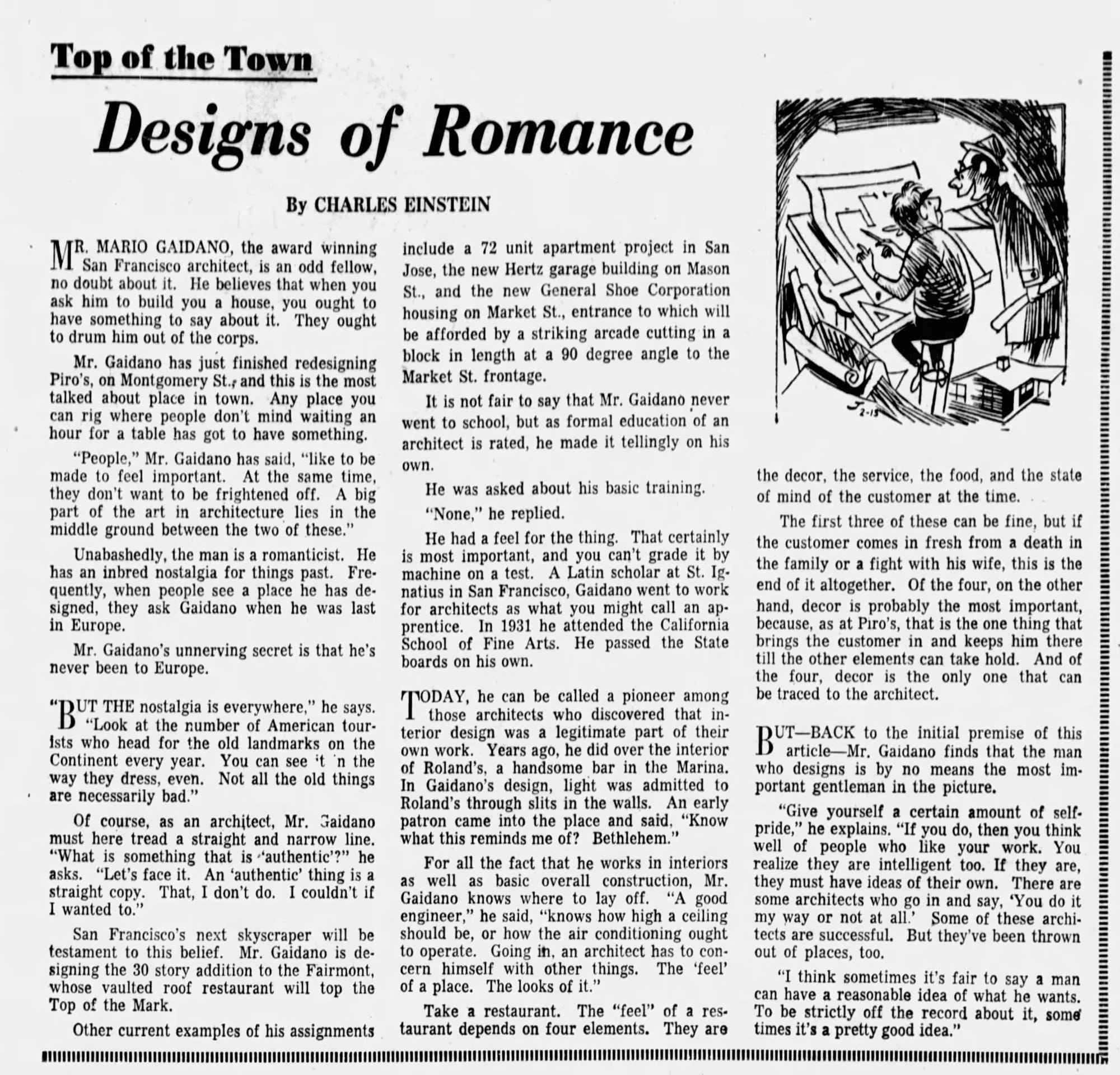

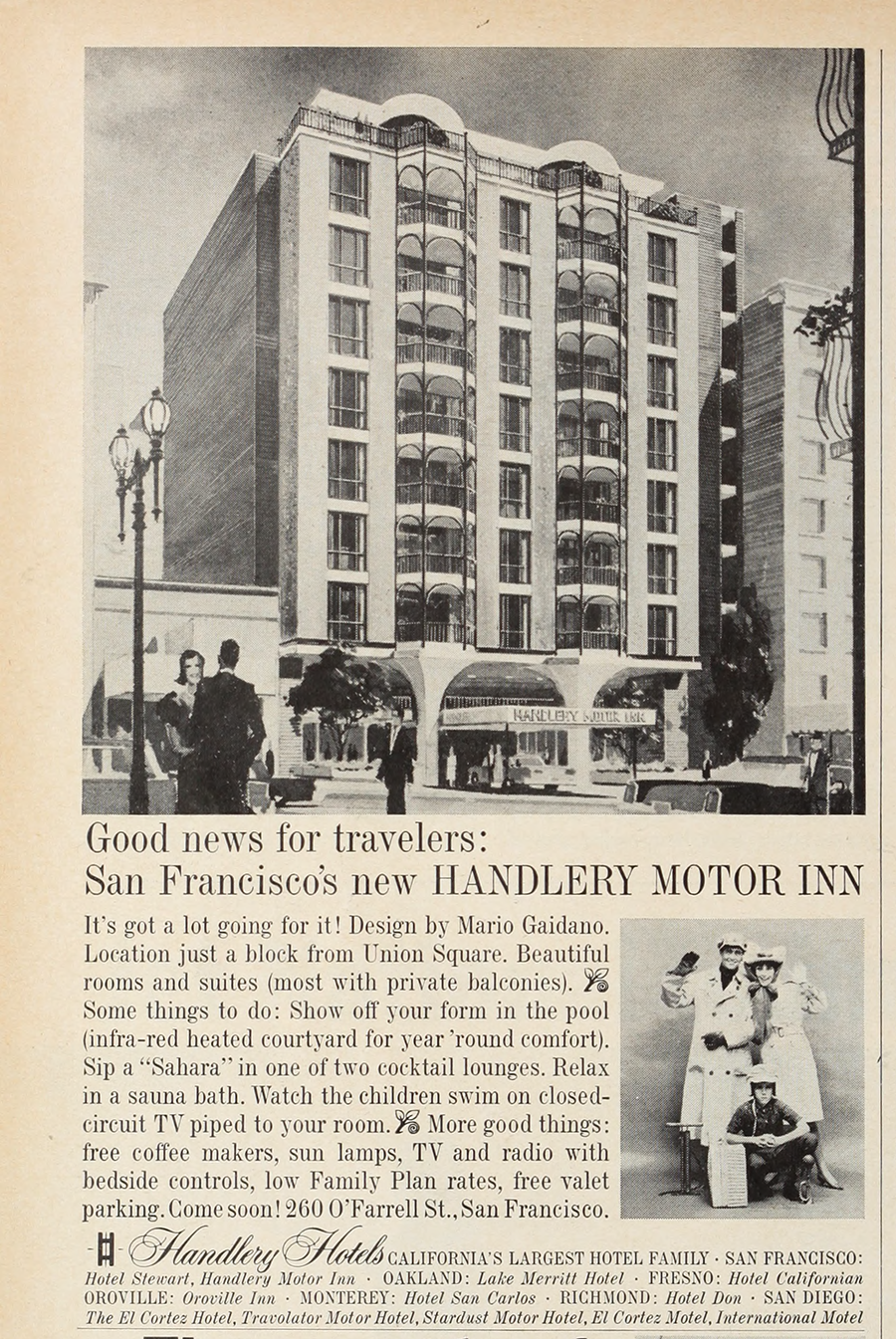

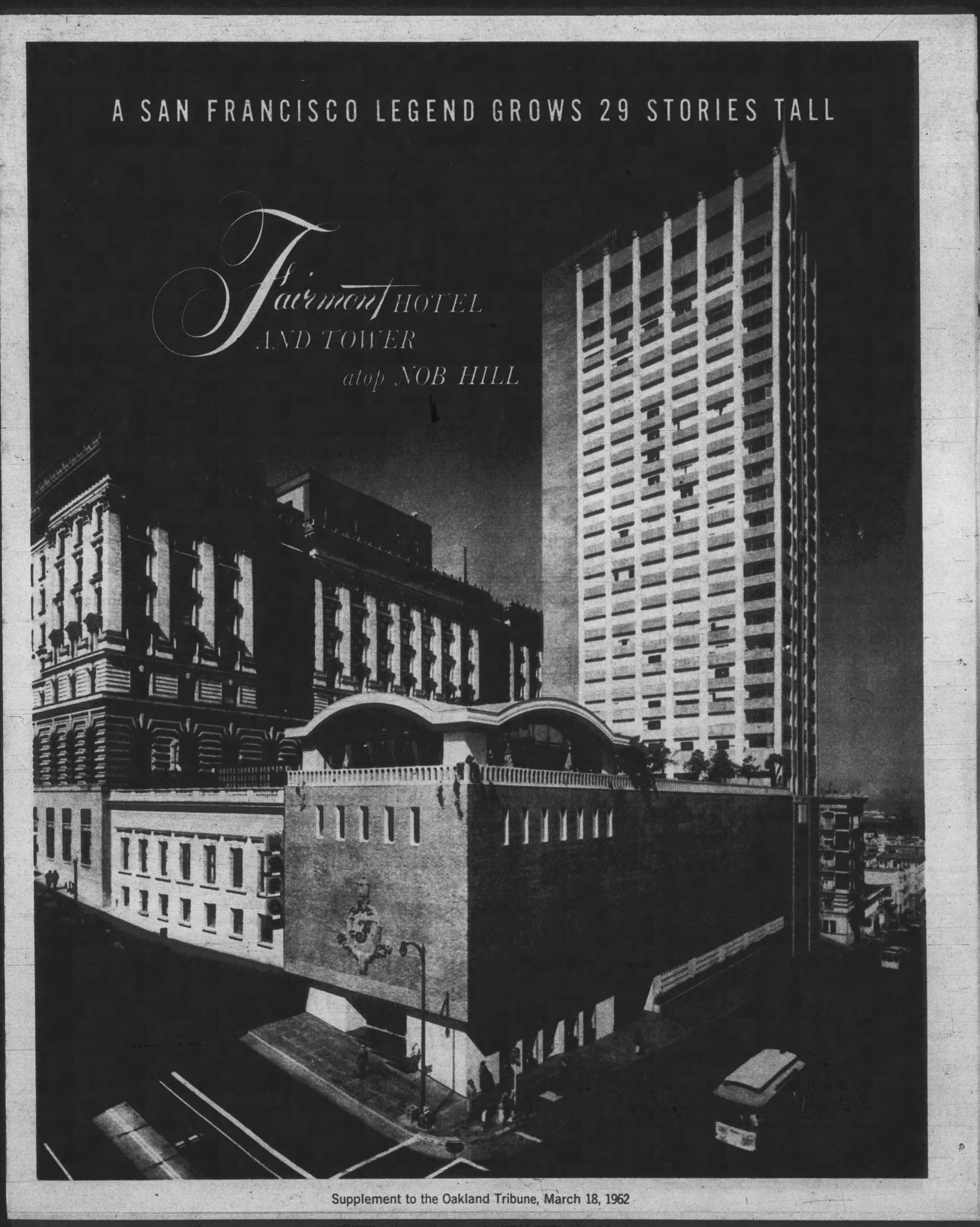

The Swig family bought the Fairmont in 1945. Part of the widespread decline in residential hotels, they quickly stopped offering permanent rooms, but the Swigs’ big swing came in 1959, when they hired architect Mario Gaidano to design a 29-story tower and conference center addition. Specializing in hospitality design, Gaidano’s firm did a bunch of hotels and restaurants in the Bay Area in the 1950s and 1960s, including the Handlery Hotel Union Square Annex, the House of Prime Rib, Alioto’s, etc. Completed in 1961, the Fairmont Tower was intentionally built just a bit taller than its rival across the street, the Mark Hopkins Hotel and its Top of the Mark bar.

1959 article on the new tower in the S.F. Examiner | 'Nob Hill Hotel', in Architectural Record, 1960, the Internet Archive | Two articles on the start of construction in January 1960 | tower construction photo, 1960, OpenSFHistory / wnp27.5165 | under construction in a Bethlehem Steel ad, 1961 in Civil Engineering, the Internet Archive | under construction in the background in a Bethlehem Steel ad, 1961, in Engineering News-Record, the Internet Archive | topping out in 1961 | in an aggregate ad

Reviews at the time were negative, with architecture critic Allan Temko saying, “It will irreparably mar the scale and mood of the massive granite pile”, and another critic calling it “regrettable”. In the 2010s, the city’s Historic Preservation Commission described it as “completely inappropriate," and argued that any proposal involving demolition should be judged as if it was an empty site (meaning the modernist addition is worse than nothing).

The addition is…uninspired. It doesn’t help that the two best parts of it are either no longer operating or hidden from the street. Hidden from the street is a nifty rooftop garden designed by renowned landscape architecture firm Lawrence Halprin & Associates, laid out in space that Gaidano’s addition created by filling out the block.

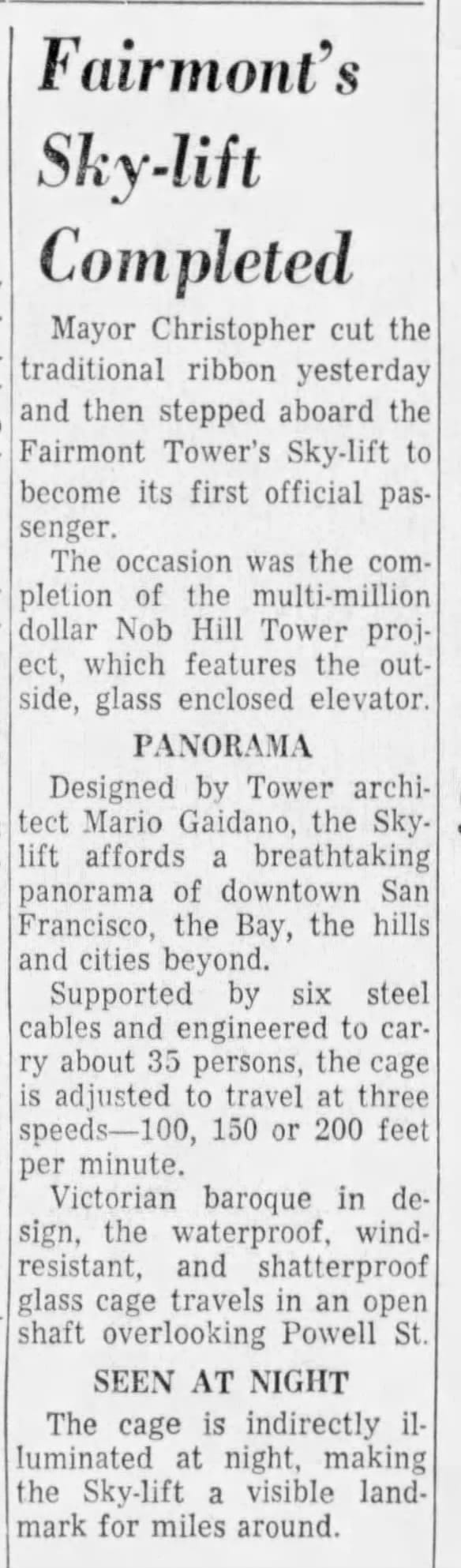

No longer operating is Gaidano’s most dramatic flourish–an illuminated glass elevator that ran up the outside of the tower, a shining symbol of the Fairmont that culminated in the top floor Crown Room Cocktail Lounge. Unfortunately, the hotel took the elevator out of service in 2002, and the Crown Room is now used mostly for private events.

'the Column of Light', plans for the illuminated elevator in the SF Examiner in 1959 | "Fairmont's Sky-lift Completed" in 1961 | undated postcard | 1962, OpenSFHistory / wnp27.3431 | 1963 from Mark Hopkins Hotel, OpenSFHistory / wnp28.1734 | 1962 with the elevator illuminated, OpenSFHistory / wnp25.6499 | 1969 with the Golden Gate Bridge in the background, OpenSFHistory / wnp25.3004

Rooftop garden, 1962, OpenSFHistory / wnp27.3427 | 2011, Frank Fujimoto, Flickr

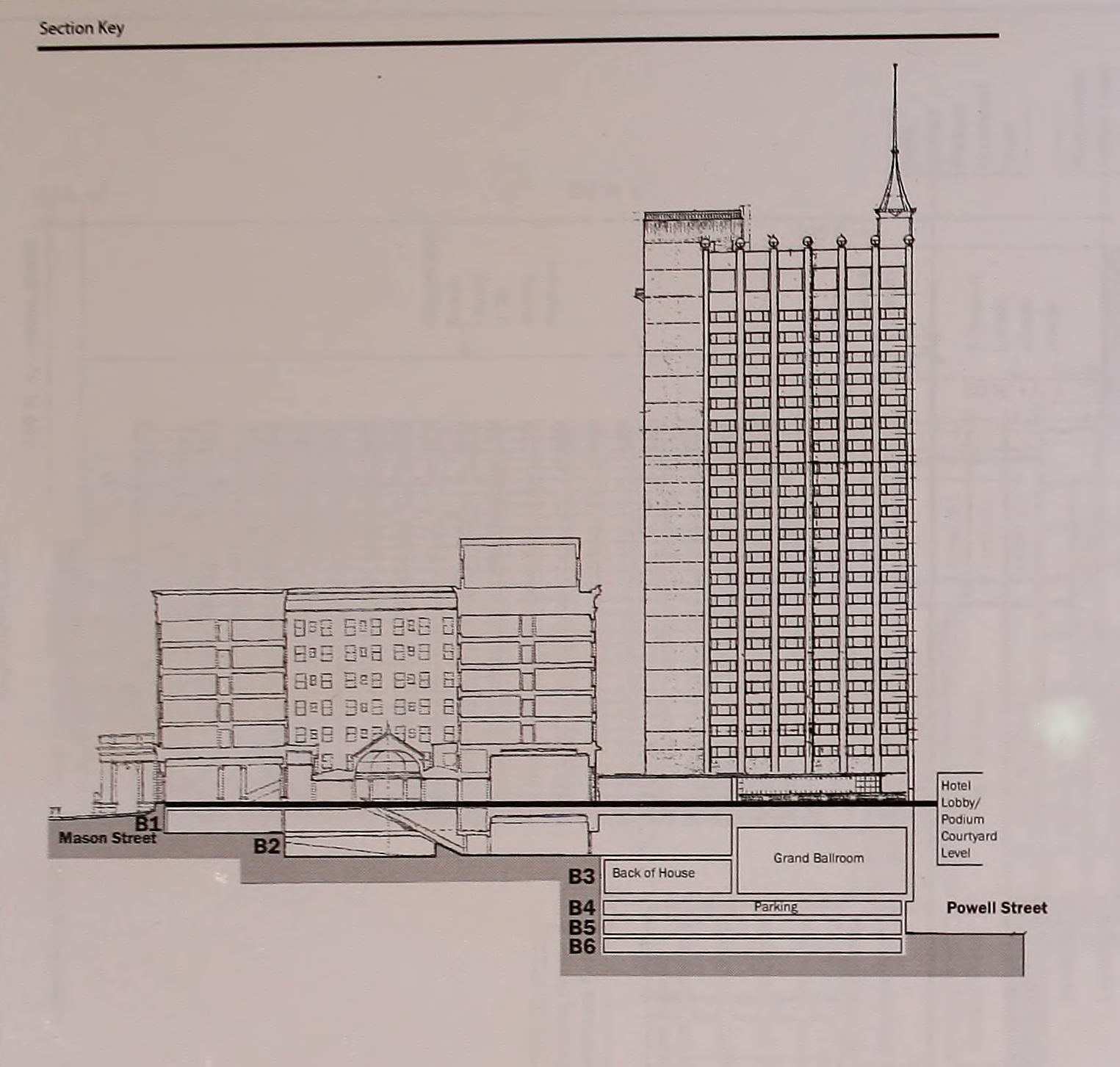

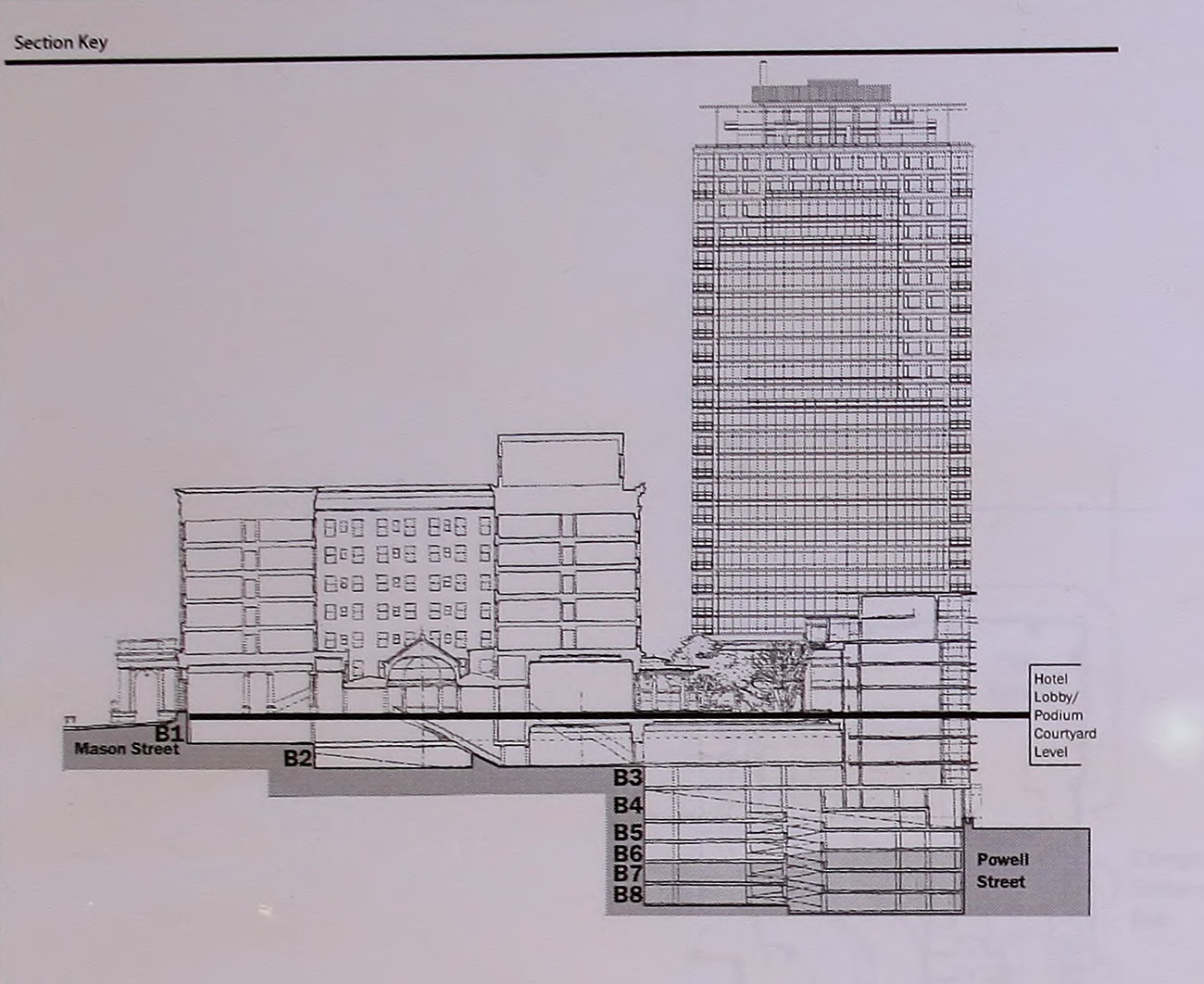

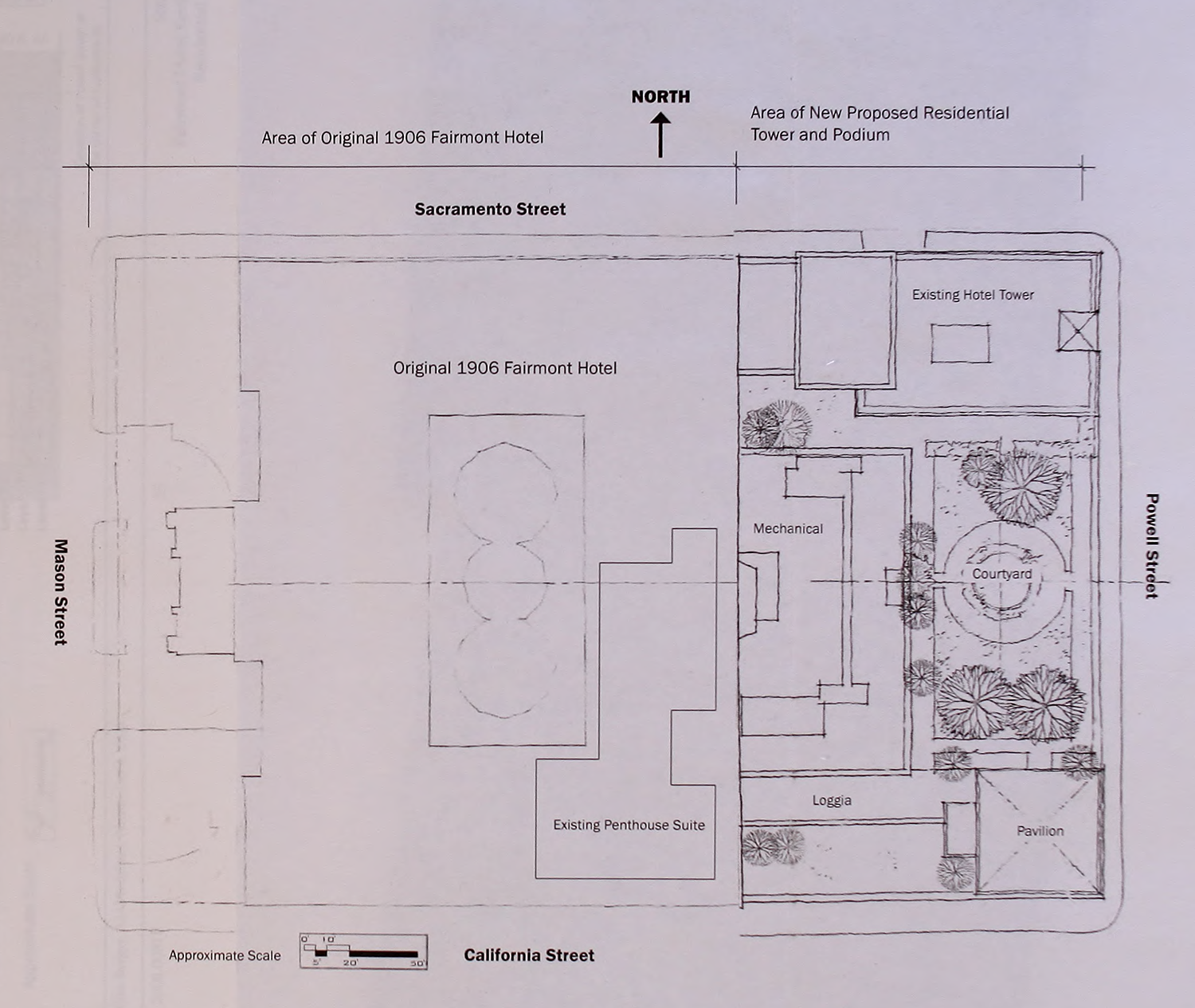

With the tower aging and the original Fairmont Building in need of a refresh, in the mid-2000s the Fairmont owners pitched a plan to demolish the 1961 addition and replace it with condos. The hotel tower would be replaced with a condo tower at the exact same height, and the event center would be replaced with a midrise condo building, with the proceeds from the condo sales financing the renovation of the century-old Fairmont original.

The owners tapped architect Miles Berger design it and, after completing an incredibly detailed Environmental Impact Report, the project went to the San Francisco Planning Commission for a vote in 2010. Not without controversy–there were concerns about the loss of unionized hotel jobs and the project launched amidst an environment opposing condo conversions of hotels, spurred by the perception that such conversions were cash grabs that didn’t address the underlying housing issues (which be true, but those issues also haven’t improved at all in the subsequent 20 years).

Maybe the loudest protests came from fans of the Fairmont’s Tonga Room, an old-school tiki-themed bar that faced demolition under the condo plan. Noticeably absent were any pleas on behalf of the Gaidano buildings themselves–although again, more than anything, demolishing it for a tower of the same size seems like a ridiculous waste of the carbon emissions spent to build the 1961 tower.

2010 and 2011 on the plans to demolish the tower and addition to replace them with condos | Elevation studies and site plans from the 2009 Environmental Impact Report, the Internet Archive

The Planning Commission vote deadlocked 3-3, which constituted a rejection, and the plan died. The owners, investment group Maritz & Wolff, had argued that the hotel wasn’t profitable and the condo tower plan was the only way to pay for a makeover of the original hotel. However, after the condo plan failed, in 2012 Maritz & Wolff sold their ownership stake for a hefty profit, and the new owners spent $21m on a renovation in 2014 (...and only three years after acquiring their stake, those owners cashed out for more than double their initial investment–not profitable my ass).

The Fairmont on Nob Hill is still one of the city’s most luxurious hotels and it remains the hotel of choice for US presidents–Biden and Harris actually just stayed here in November for the APEC summit. The hotel was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2002 (although it’s not a San Francisco landmark). With the demolition plans abandoned, both aspects of the Fairmont–slightly 0ver-the-top Beaux Arts and clunky 60s modernism–look like they will stick around for the foreseeable future, which seems about right. An honest reflection of 120 years of the hotel business, if not a thrilling one.

2015, Wikimedia Commons | 2015, Thomas Hawk, Flickr

Production Files

Further reading:

- The NRHP registration form

- The Environmental Impact Report submitted to the San Francisco Planning Commission in 2009 in connection with the demolition plans and also addressed by the San Francisco Historic Preservation Commission in 2009.

- In the always-excellent Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- Julia Morgan: a bunch of people way smarter than me have written about her.

- Alexandra Lange wrote up a nice belated obituary as part of the New York Times 'Overlooked' series.

- There's a good 99% Invisible episode about her

- Book-length biographies: Julia Morgan, Architect by Sara Boutelle, Julia Morgan: Architect of Beauty by Mark Wilson, Victoria Kastner’s Julia Morgan: An Intimate Biography of the Trailblazing Architect

- Some great photos in this strong Saving Places article about her

- John King for SFGate in 2010, "Fairmont makeover a chance for S.F. to shine"

- In the Nob Hill Gazette, 'Tales from the Fairmont'

Mario Gaidano isn't especially well-known today, but he was one of the most prolific architects of restaurants and hotels in the Bay Area in the 1950s and 1960s (many of which have since been remodeled or demolished...which is entirely understandable, gotta keep a restaurant design fresh). At Fior D'Italia, which he designed, they apparently even named a roast beef dish after him.

Articles about Mario Gaidano and projects he was working on from the late 1950s into the 1960s

1961 in an air conditioning ad, Heating, Piping and Air Conditioning, the Internet Archive | in a 1961 Bethlehem Steel ad, Civil Engineering, the Internet Archive | Two pages from a multi-page supplement in the Oakland Tribune in 1962

1945, OpenSFHistory / wnp14.4654 | 1947, Emiliano Echeverria/Randolph Brandt Collection, OpenSFHistory / wnp32.0229 | 1955, OpenSFHistory / wnp27.1616 | 1957, OpenSFHistory / wnp25.4592 | 1963, OpenSFHistory / wnp25.3565 | 1989, Emiliano Echeverria Collection, OpenSFHistory / wnp32.2890 | 1989, 100th anniversary of the Powell Line cable car, Emiliano Echeverria Collection, OpenSFHistory / wnp32.2898

Member discussion: