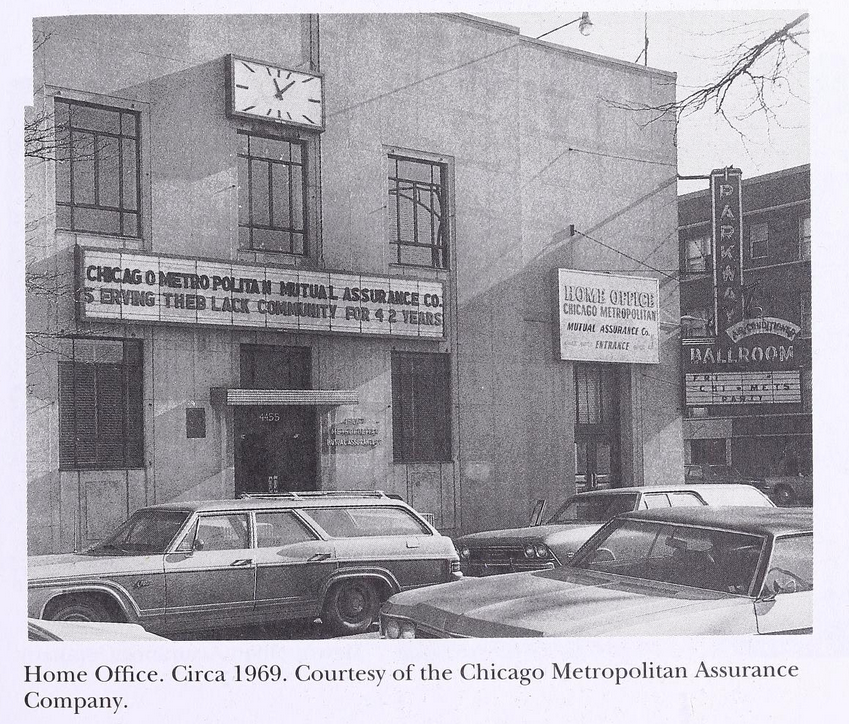

At a time when insurers like Prudential were pioneering new frontiers in racism–providing inferior coverage for the same price or flat-out refusing to accept Black policyholders–the rise of Black insurers like the Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company embodied “making a way out of no way”. Having made their way, CMMAC opened their new Bronzeville headquarters here in 1940, with a unique asset for the community on the second floor–the Parkway Ballroom. The Parkway Ballroom was one of the premier places for Black Chicagoans to dance, date, and demonstrate, holding everything from wedding receptions and business banquets to Operation Breadbasket meetings led by Jesse Jackson.

The cruel irony for Black financial institutions like the Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company was that racial integration was a one-way street–suddenly competing for African American customers against corporate giants, but completely shunned by white customers, their business declined. The Parkway Ballroom closed in 1974, and in 1991 Atlanta Life Insurance Company acquired a struggling CMMAC. In a positive revival, though, Chef Cliff Rome reopened the Parkway Ballroom in 2002 and it remains a vibrant event venue in Bronzeville. Fittingly, in 2021 the Bronzeville Historical Society also moved in.

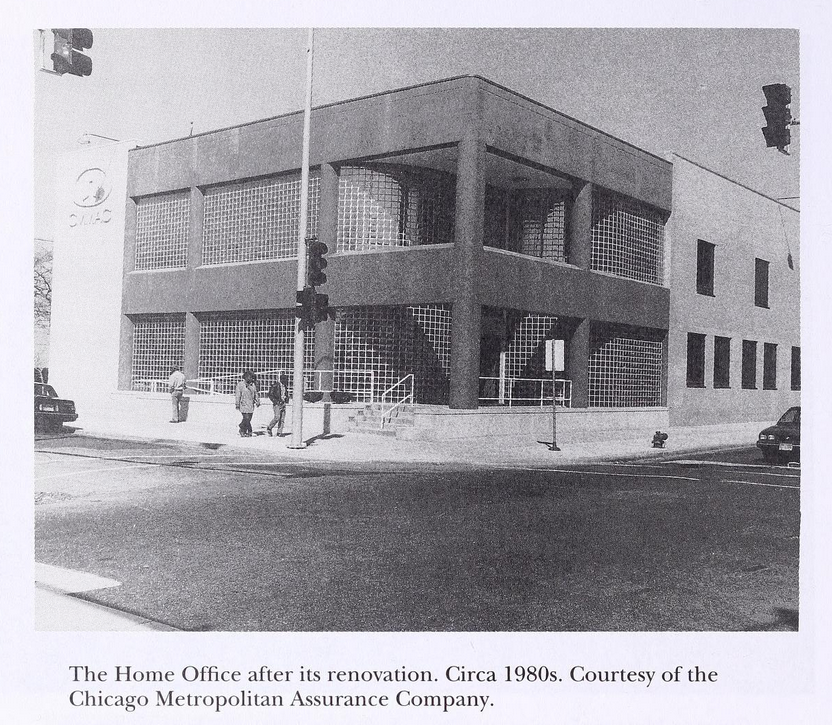

So, what’s changed? Well, it’s the same bones under that facade, but other than that this building is unrecognizable after a 1984-1985 renovation gave the building its present postmodern appearance.

...and you know what, I think I prefer it this way. This is a neat, relatively uncommon example of 1980s architectural exuberance on the South Side and it means that we’ve had two wildly different, effortlessly cool iterations of the Parkway Ballroom.

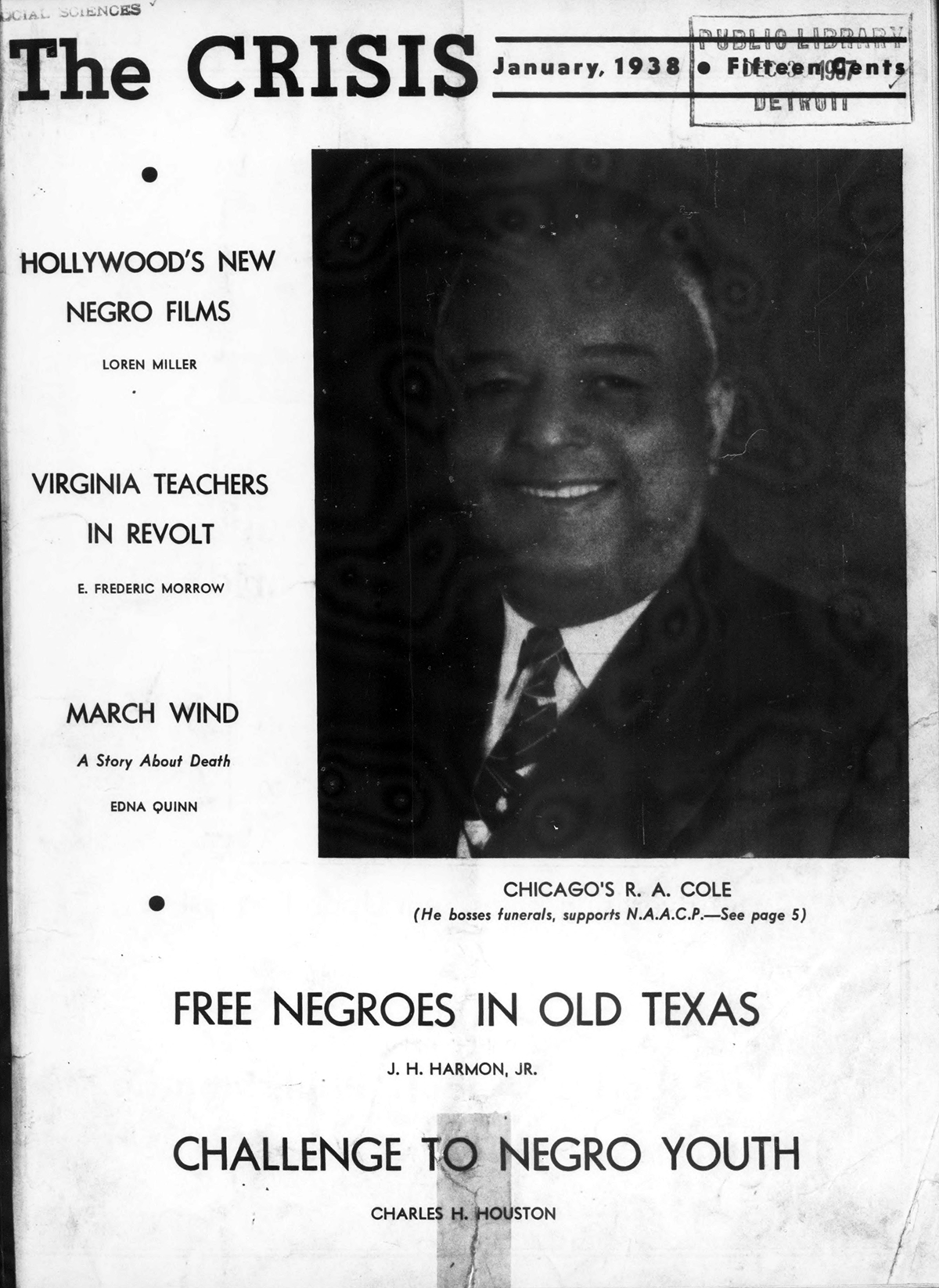

Founded in the 1920s as a burial insurance company for Chicago’s Black working class, under the leadership of Robert Alexander Cole the Metropolitan Funeral System Association evolved into the Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company, one of the pillars of Chicago’s Black business community.

In The National Underwriter Life Insurance Edition, 1935, the Internet Archive | Businesses on Chicago's South Side, 1938, Chicago Public Library | Robert A. Cole on the cover of The Crisis, 1938, the Internet Archive | 1940 in the official program for the American Negro Expo, the Internet Archive

Daniel McKee Jackson, underworld kingpin and undertaker (quite a combo), founded the Metropolitan Funeral System Association in 1925. Busy with his gambling empire, in 1927 Jackson handed control to Robert Alexander Cole. Born in Tennessee, Cole arrived in Chicago as part of the Great Migration. He remembered his own–burials insured by the company could be performed within a 1,000 mile radius (migrants to Chicago often wished to be buried back home). Like every crisis in US history, the Great Depression disproportionately devastated Black business, but Cole subsidized the company with his gambling winnings to keep it afloat.

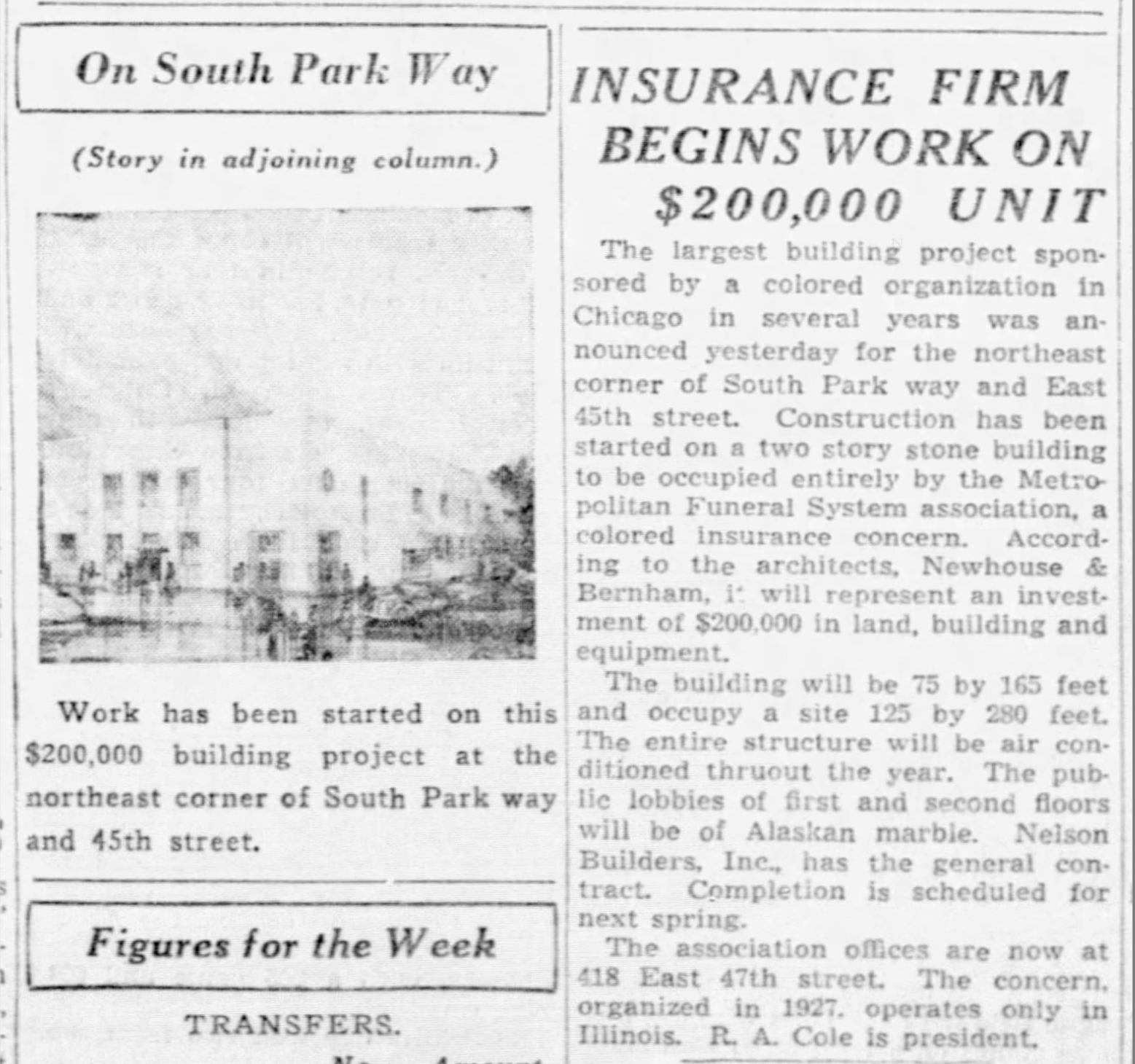

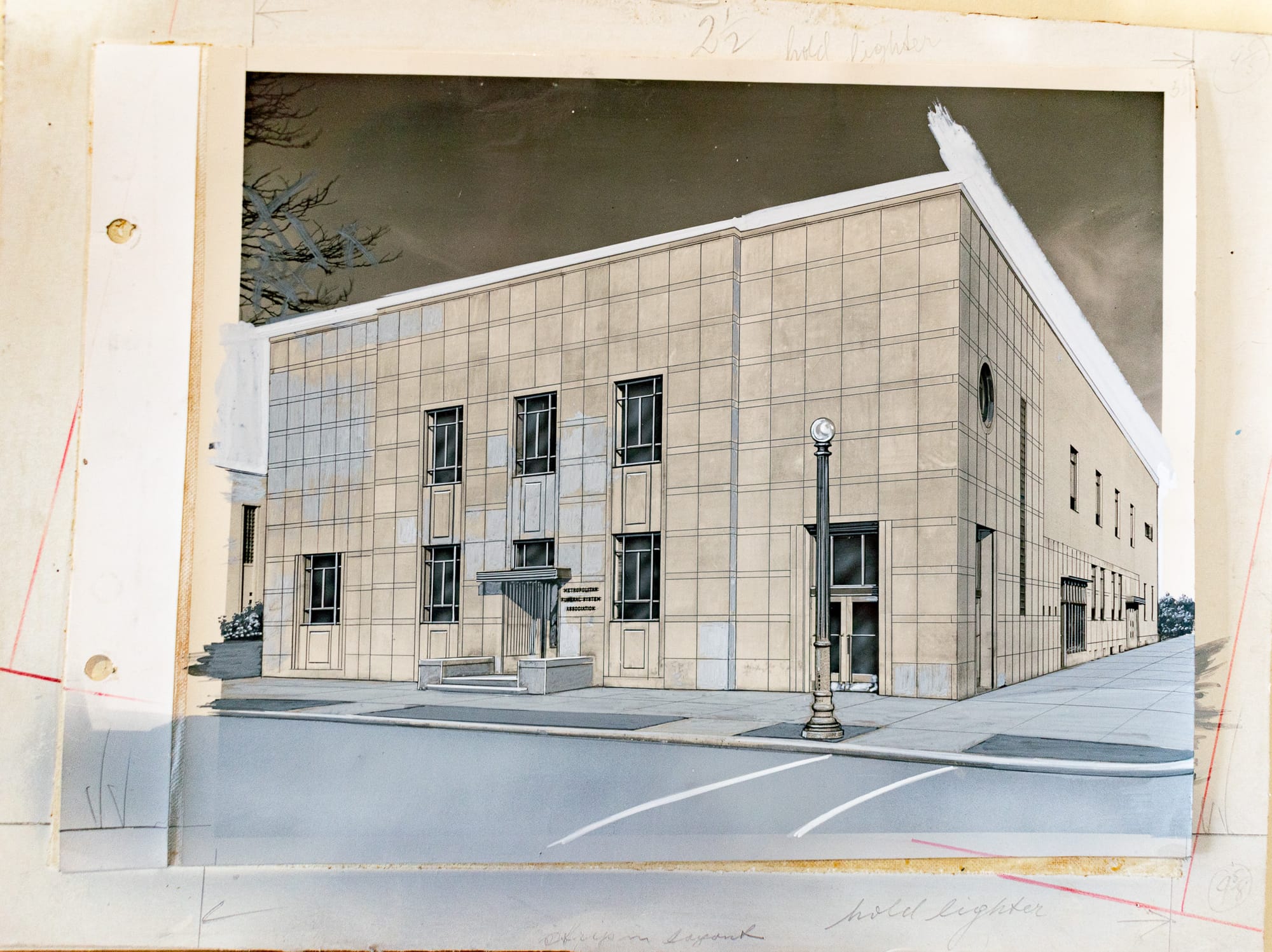

1939 Chicago Defender and Chicago Tribune articles on the building breaking ground | 1940 rendering of the building in the Chicago Defender

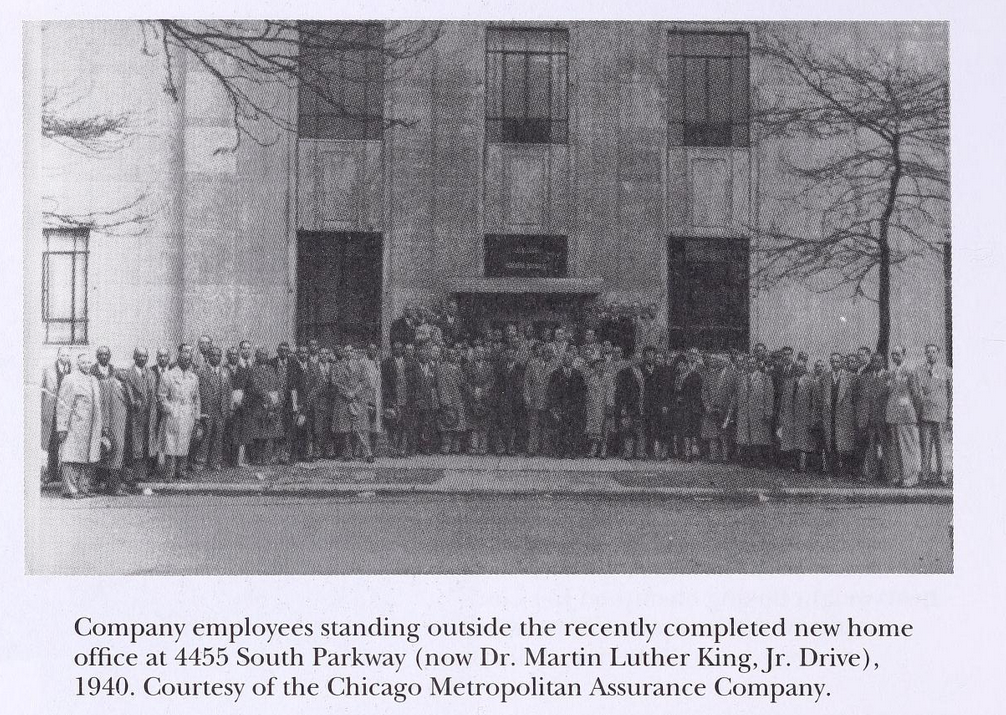

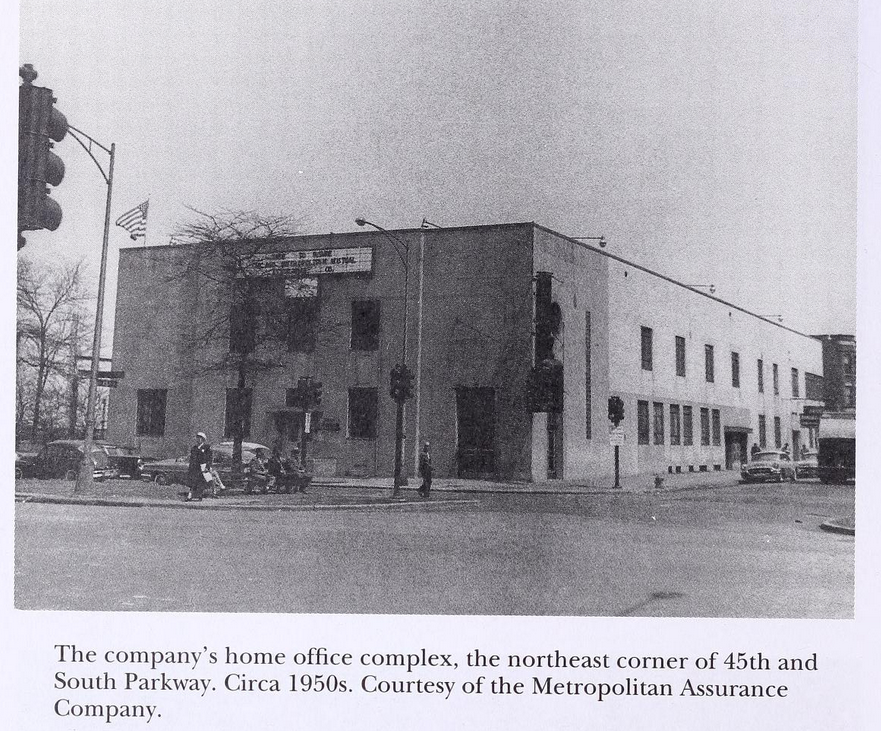

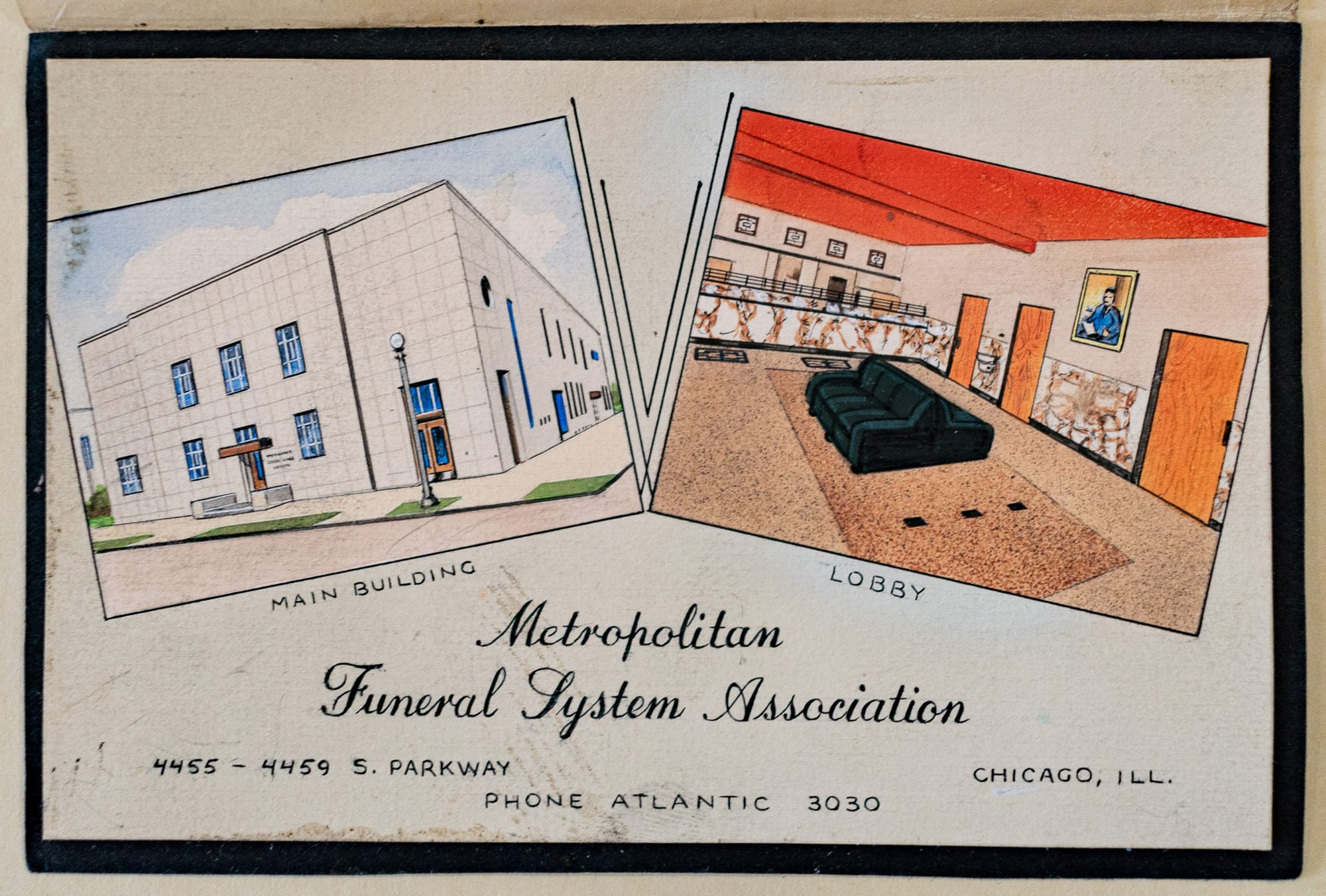

Metropolitan rebounded strongly, and the company hired Newhouse & Bernham to design a new headquarters on the corner of 45th & South Parkway (now MLK Drive). Henry Newhouse was long dead and the firm had probably peaked in the 1910s, but they were very active on the South Side. The architecture firm delivered an austere Art Moderne rectangle with insurance offices on the first floor and the Parkway Ballroom–sort of operated as a loss-leading community asset by the insurance company–above. The Parkway Ballroom was part of Robert A. Cole's broader desire to independently provide for the Black community–the other ballrooms and banquet halls in the area at the time were either in disrepair or owned by white people. Cole and Metropolitan also owned radio programming, the Bronzeman magazine, and the Chicago American Giants in the Negro Leagues.

A 1949 addition to the back of the building added more office space as well as the Parkway Dining Room, a high-class restaurant.

1940 photo | 1949 article about the renovation to the back, the National Underwriter, the Internet Archive | 1950s photo | 1951 photo, the Chicago Defender

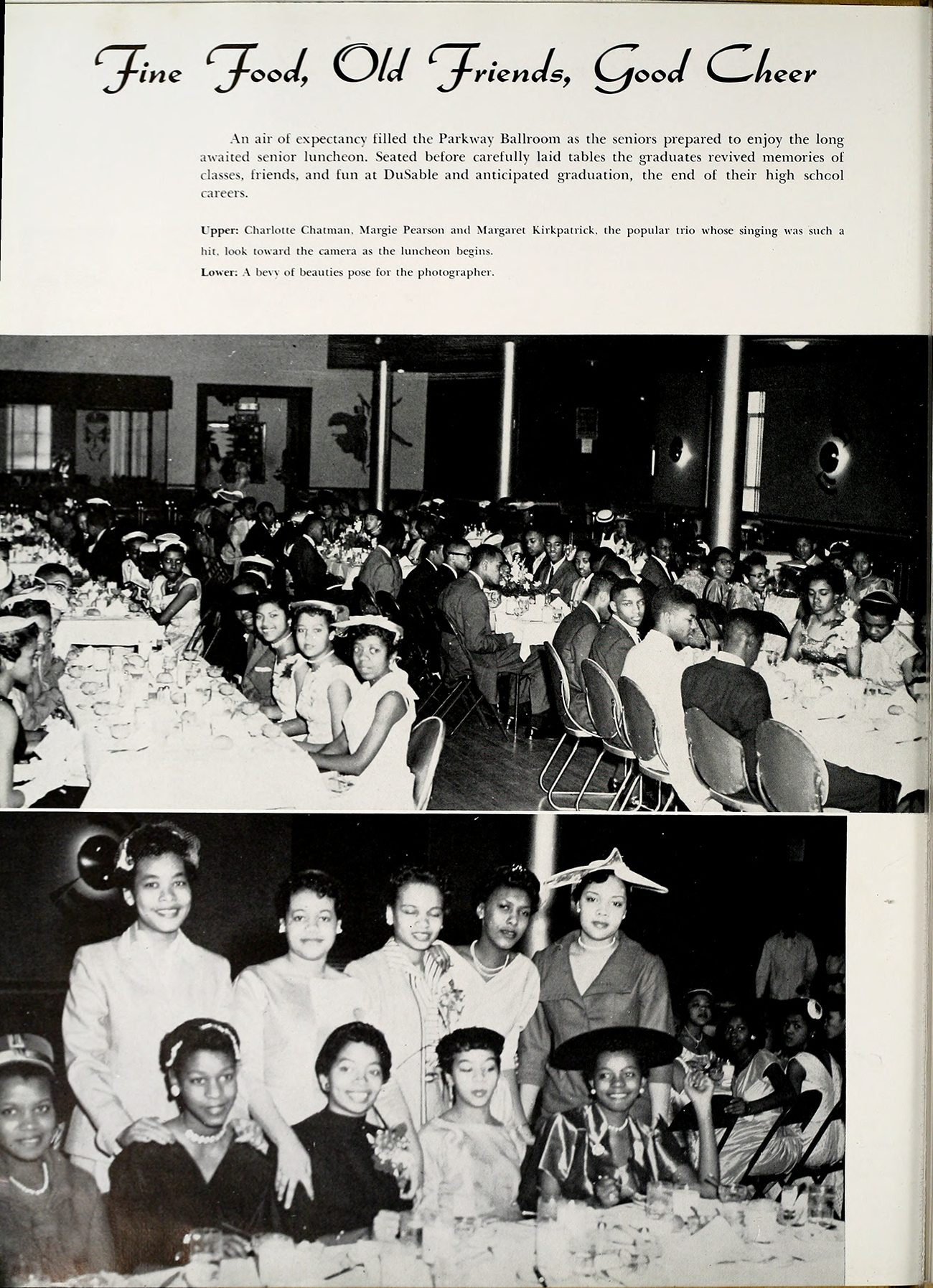

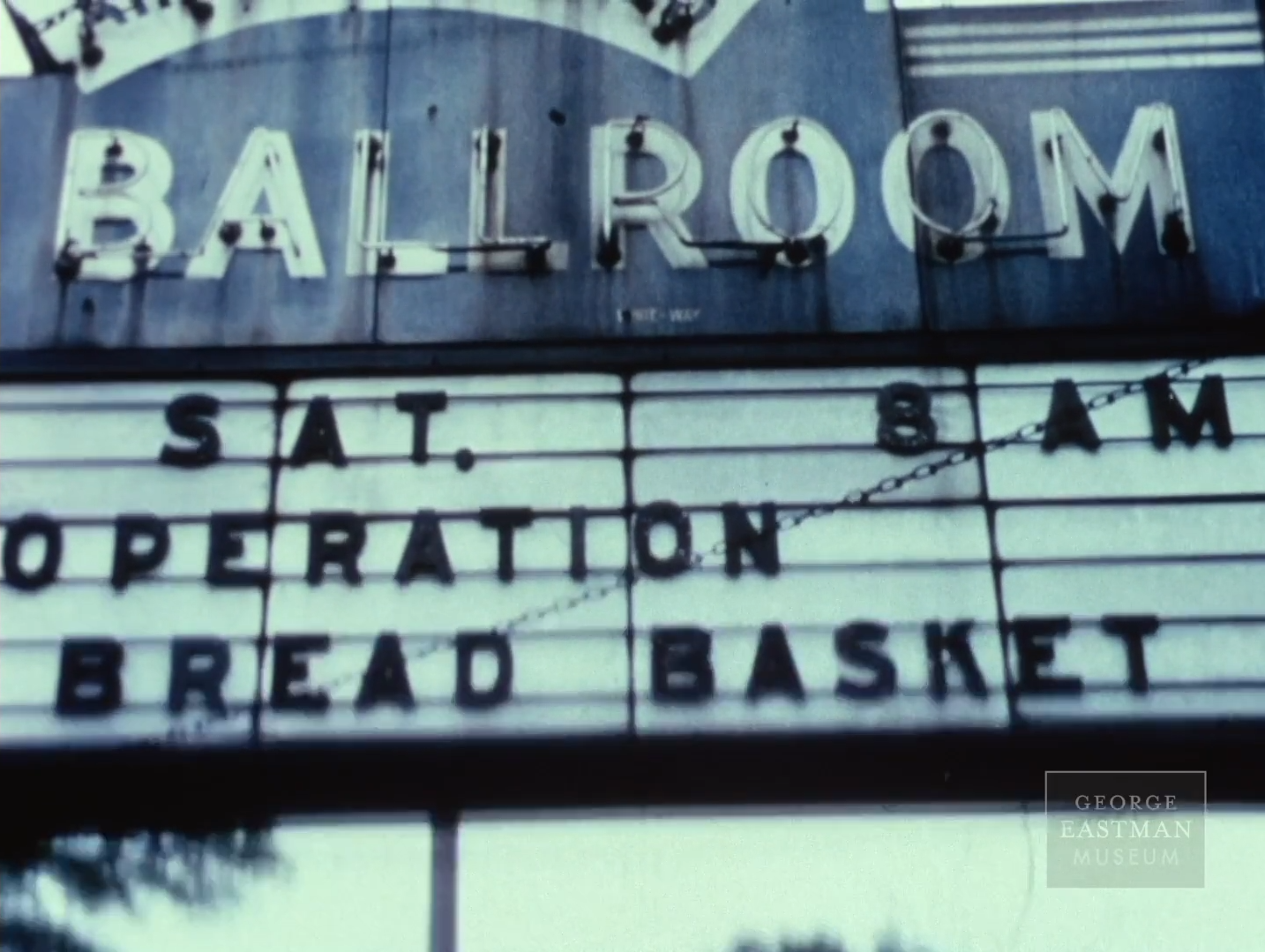

Duke Ellington, Sammy Davis Jr, Count Basie, and Ella Fitzgerald are among the musicians who played the Parkway at its peak, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr and Langston Hughes attended banquets here. It wasn’t only a playground for the famous–Parkway Ballroom was the setting where thousands of Chicagoans celebrated key life events–but it’s fun to see where those two lines crossed. In my favorite example of that intersection, legendary singer Mavis Staples had her (first) wedding reception here in 1964. In the late 1960s, the Parkway Ballroom was a key organizing site for Operation Breadbasket, the activist effort led by Rev. Jesse Jackson to boycott businesses who didn’t hire Black workers or who offered subpar service to Black customers.

DuSable High School Senior Luncheon, 1956, the Internet Archive | Mavis Staples to wed, 1964, the Chicago Defender | Sammy Davis Jr. performs, 1957, the Chicago Defender | Langston Hughes to speak at Parkway Ballroom, 1957, the Chicago Defender | stills from Operation Breadbasket, 1969, the George Eastman Museum |

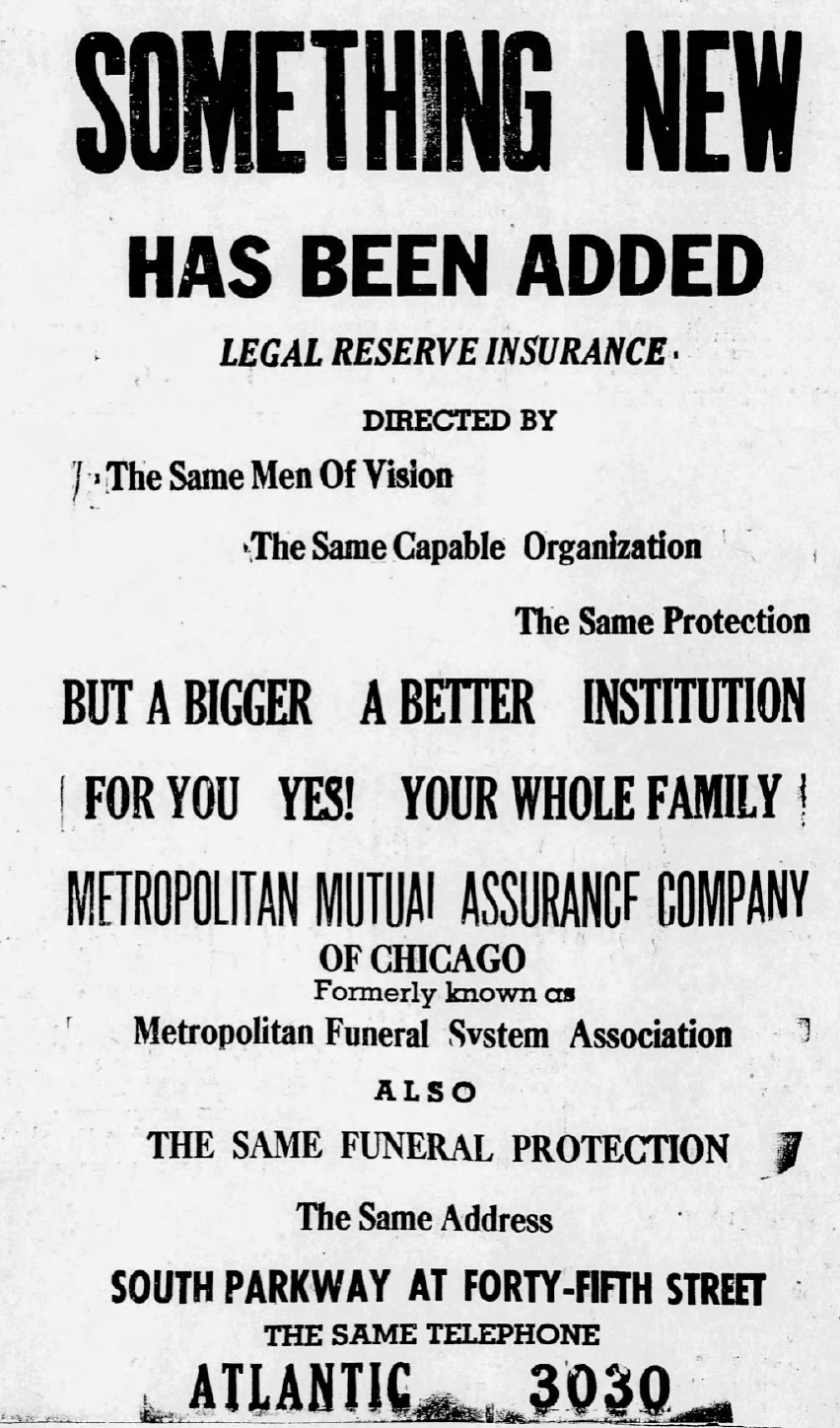

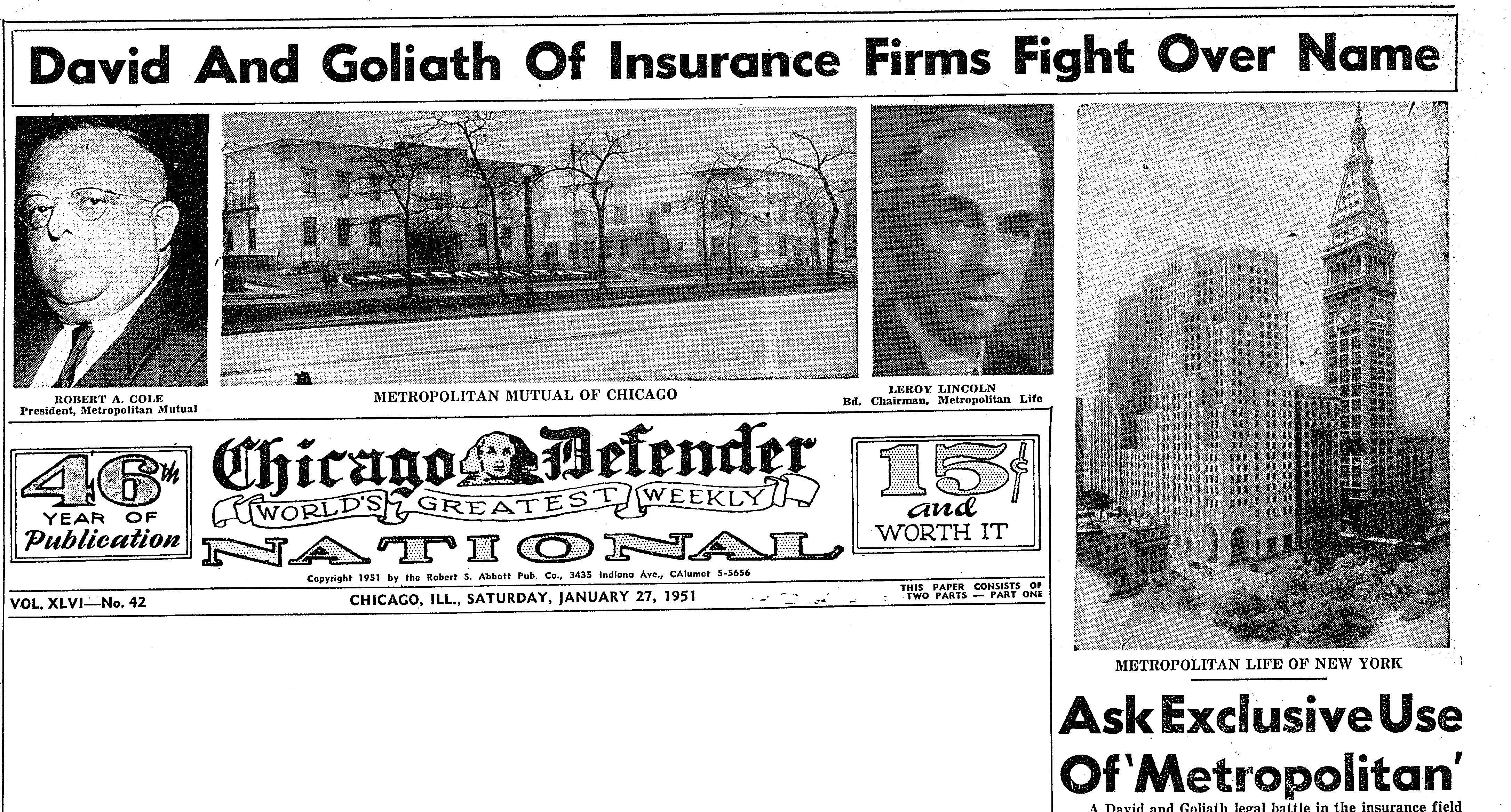

The Metropolitan Funeral System Association had expanded into life insurance in 1946, renaming itself Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company. This caught Metropolitan Life’s attention. In a David vs. Goliath court case in 1951, MetLife sued Metropolitan Mutual for trademark infringement. The legal realities aside, this was bullshit–MetLife refused to hire Black agents and Metropolitan Mutual catered exclusively to the Black market. MetLife won an empty victory, with Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company forced to change their name to Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance.

1946 ad about insurance expansion | 1951 headline on the lawsuit by MetLife, the Chicago Defender | 1969 photo

In the 1940s, some Black insurers outperformed their white peers, and the real trouble for CMMAC came when the white corporate world began to recognize the buying power of Black America. Suddenly, there was competition for Metropolitan Mutual’s core market. As overt discrimination decreased in the 1950s and 1960s, Black customers increasingly patronized downtown companies and major corporate insurers, and those corporations began to hire Black agents as well. The Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company's efforts to hire white agents and compete for white customers was doomed to fail–for Black businesses, racial integration was a one-way street. Labor strife sparked by differential treatment between Chicago-based agents and those employed elsewhere also hurt CMMAC’s competitive position.

Intense population density had helped foster Bronzeville’s (and thus CMMAC’s and the Parkway Ballroom’s) vitality–but this density was the twisted result of Chicago’s extreme segregation. Through legal maneuvering like racially-restrictive covenants and violent repression like the white housing riots in Deering and Englewood, white Chicago successfully kept Black Chicagoans segregated into the overcrowded confines of the Black Belt–more than 100,000 people lived in Bronzeville in 1950. As these barriers weakened (a bit) and changed shape (mostly) in the 1950s, new neighborhoods opened up and Bronzeville depopulated (urban renewal and ‘slum clearance’ also played a key role). By 1974 Bronzeville’s population had fallen to less than 60,000, the Parkway Ballroom had closed, and the Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company was in a gradual decline.

1974 articles about the closing of the Parkway Balloom in the Chicago Defender and Chicago Tribune | 1984 ad, "A New Look in 1985", the Chicago Defender | 1980s photo

After considering a move to 79th and Cottage Grove, in the 1980s CMMAC chose to renovate their old HQ instead. Despite decades of gradual decline, the company was still the 6th largest Black-owned insurer in the US when the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, another historically Black insurer, acquired it in 1991.

But this is a positive story of revitalization and rebirth. In 2002, the building was bought by clout-heavy Chicago developer and landlord Elzie Higginbottom, and the Parkway Ballroom reopened under chef Clifford Rome. Returning to its former role as a place of celebration, today the Parkway once again fundraisers, corporate events, and weddings–and, since 2021, the Bronzeville Historical Society.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Racial Desegregation and Black Chicago Business: The Case Studies of the Supreme Liberty Life Insurance Company and the Chicago Metropolitan Assurance Company by Robert Weems Jr.

- Black business in the Black metropolis : the Chicago Metropolitan Assurance Company, 1925-1985 by Robert Weems Jr.

- "Robert A. Cole and the Metropolitan Funeral System Association: A Profile of a Civic-Minded African-American Businessman" by Robert Weems Jr.

- "The Myth Of The Actuary: Life Insurance And Frederick L. Hoffman's Race Traits And Tendencies Of The American Negro" by Megan J. Wolf

- This incredible documentary about Operation Breadbasket, partially filmed inside the Parkway Ballroom

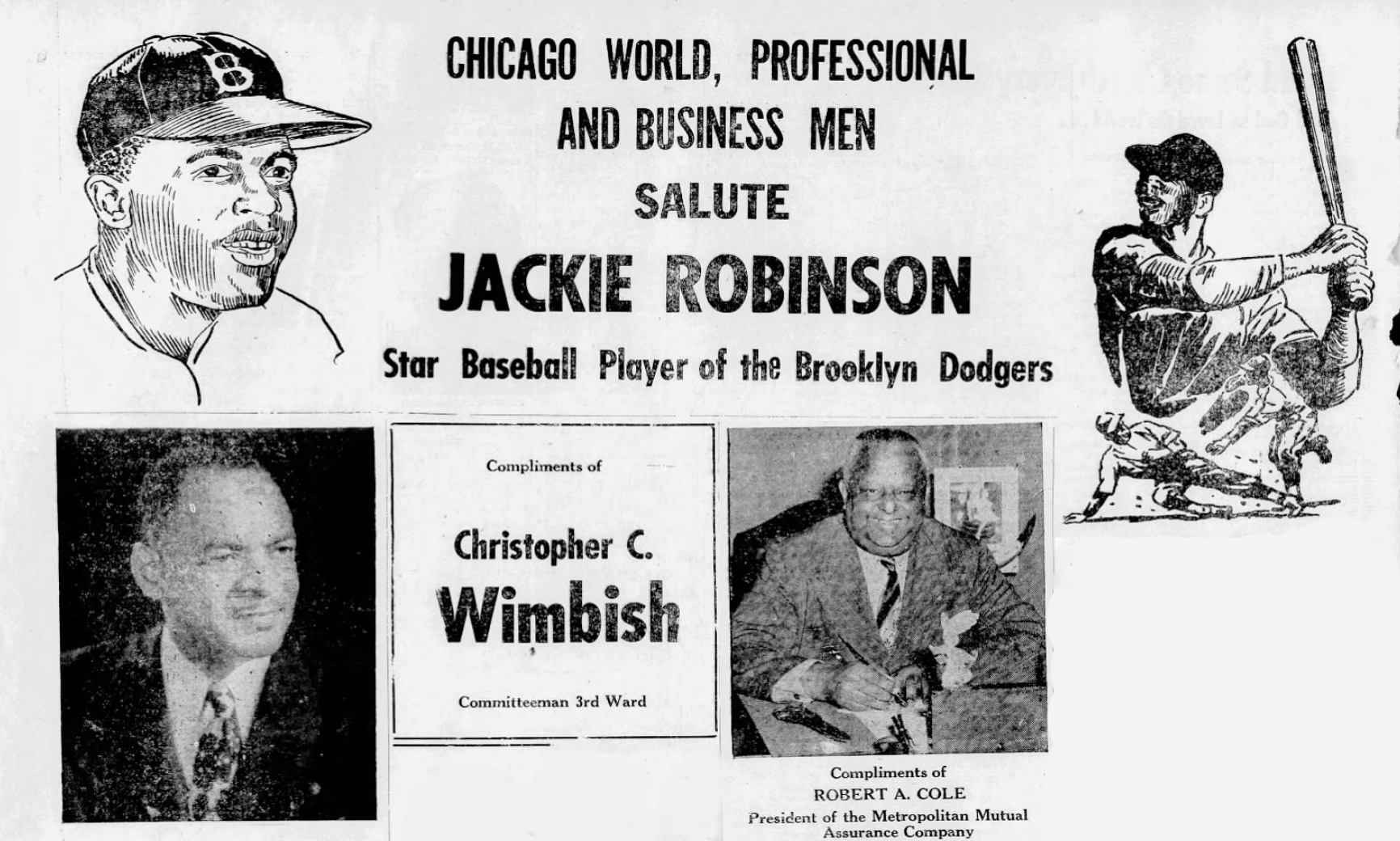

Some great 1940s and 1950s ads for MFSA/CMMAC.

1942 ad celebrating Rosh Hashanah in the Sentinel, Illinois Digital Archives | 1947 ad celebrating Jackie Robinson, the Chicago Defender | 1952, 1954, 1956 ads in Ebony, the Internet Archive

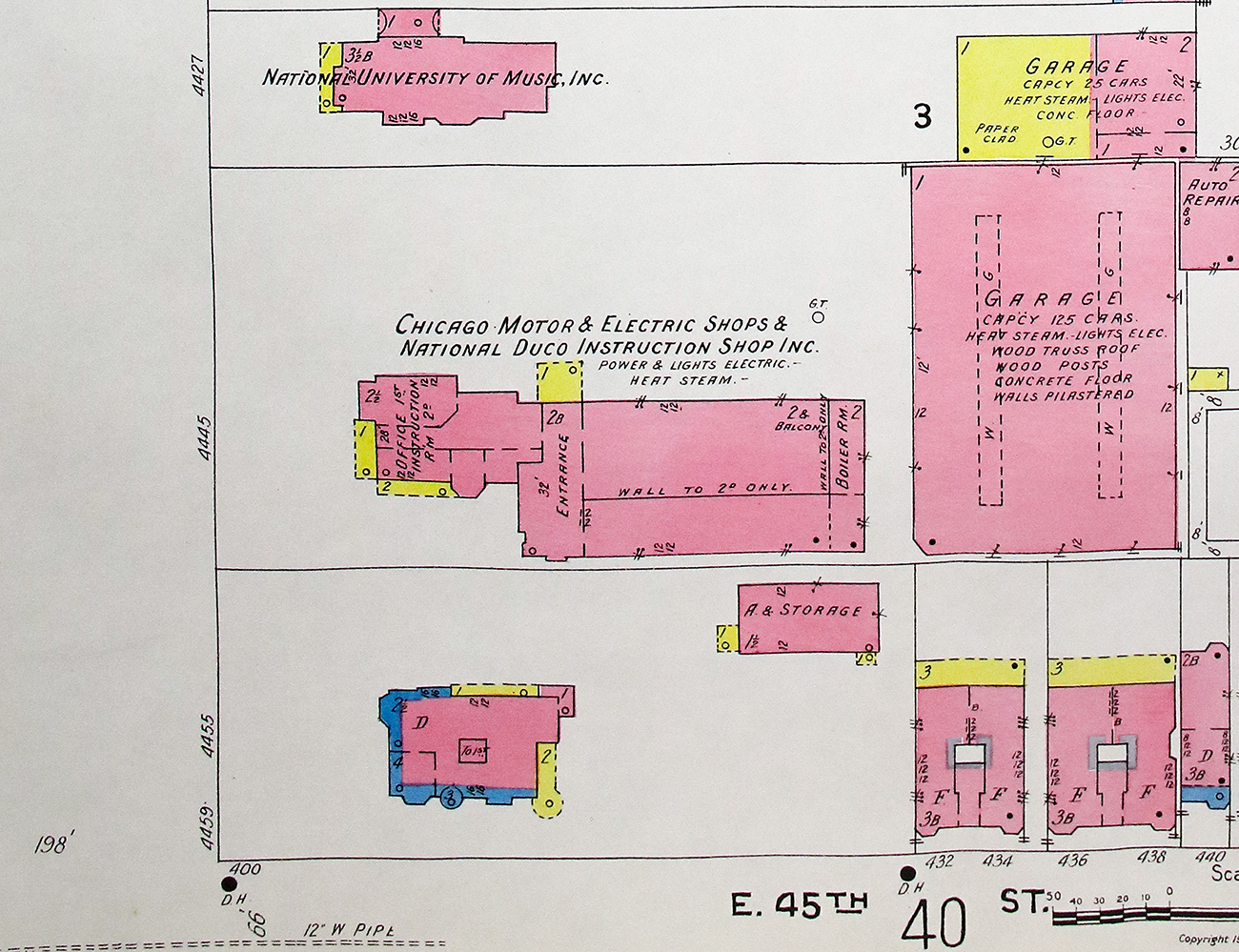

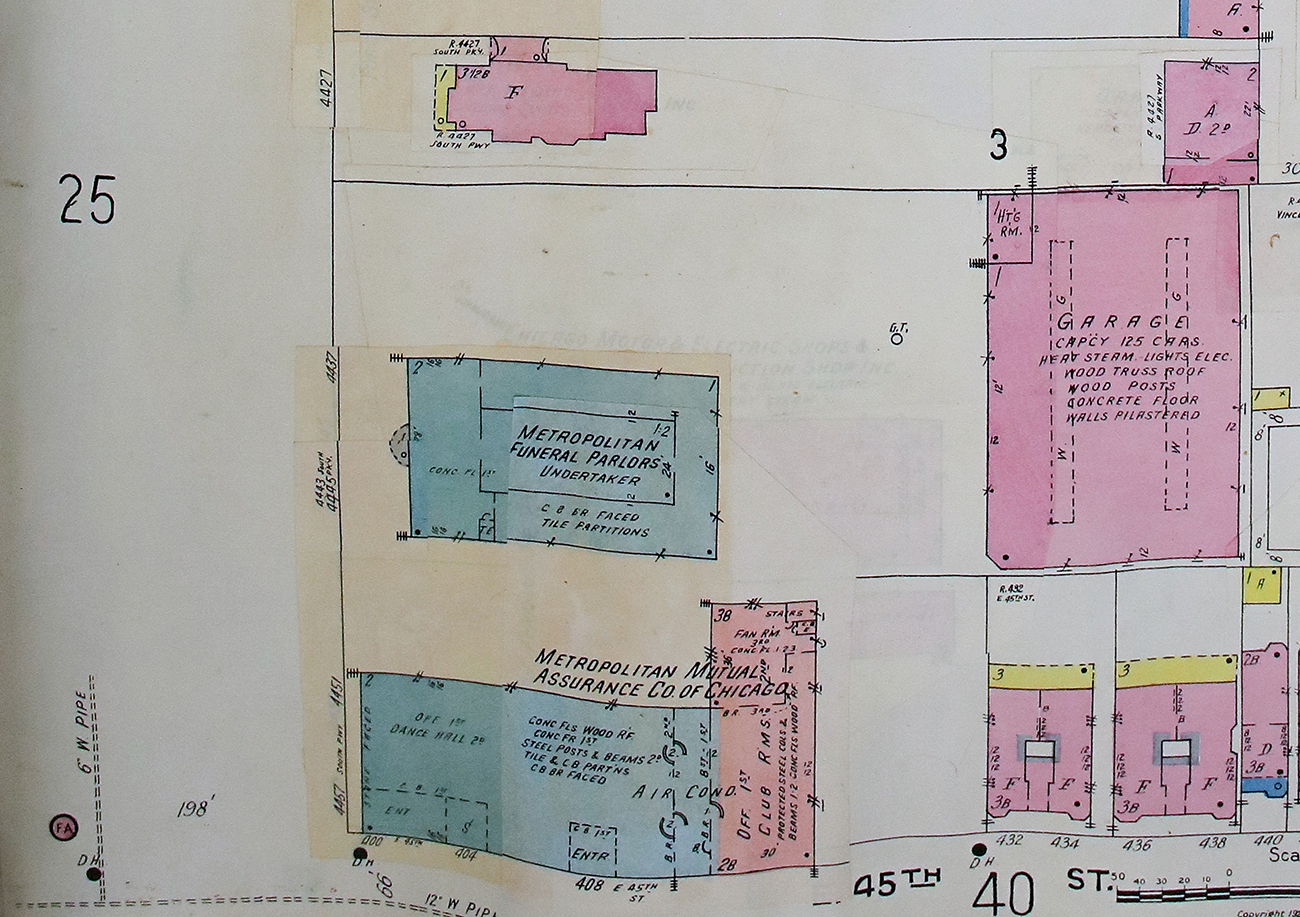

1925 Sanborn Map | 1950 Sanborn Map

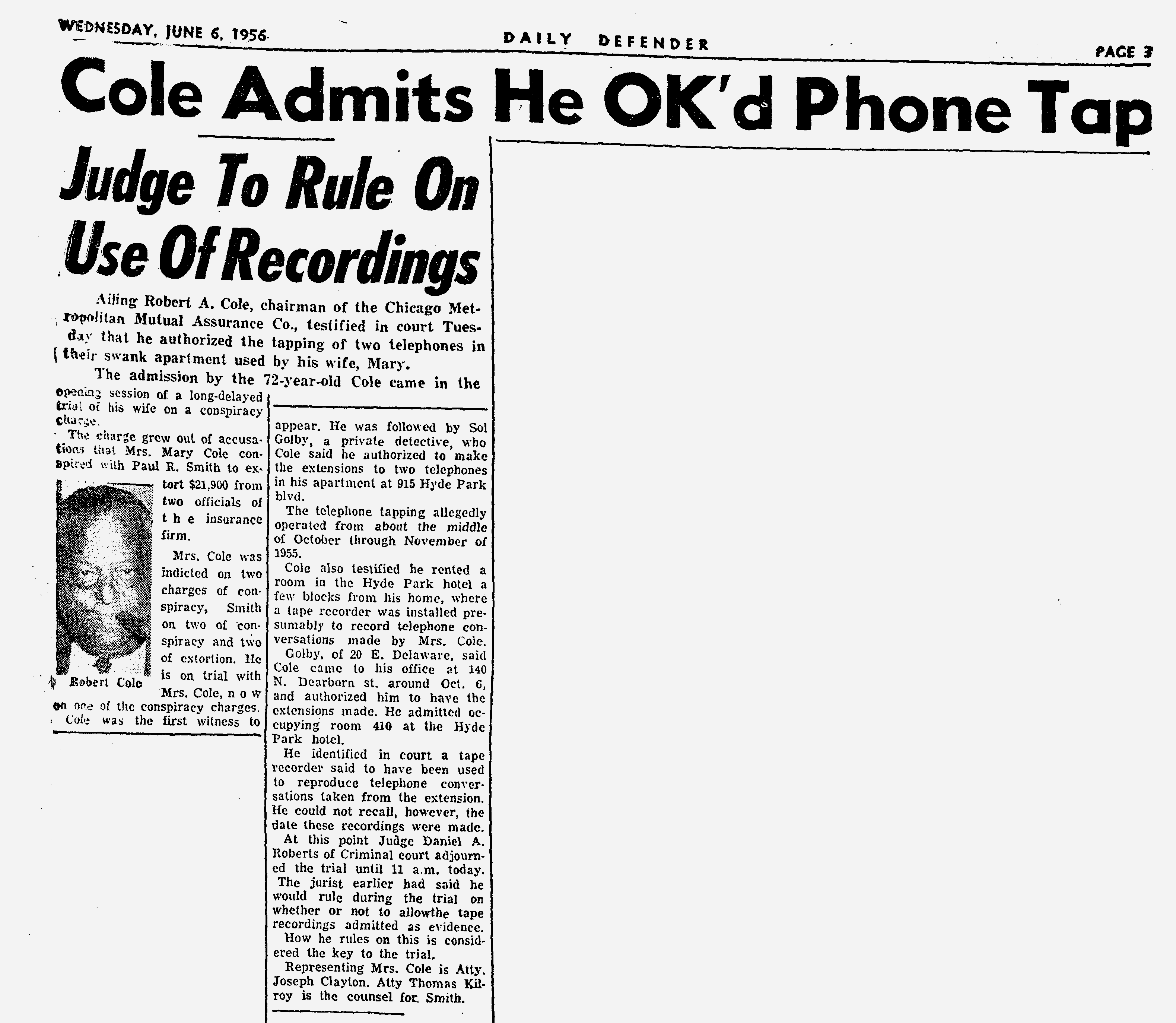

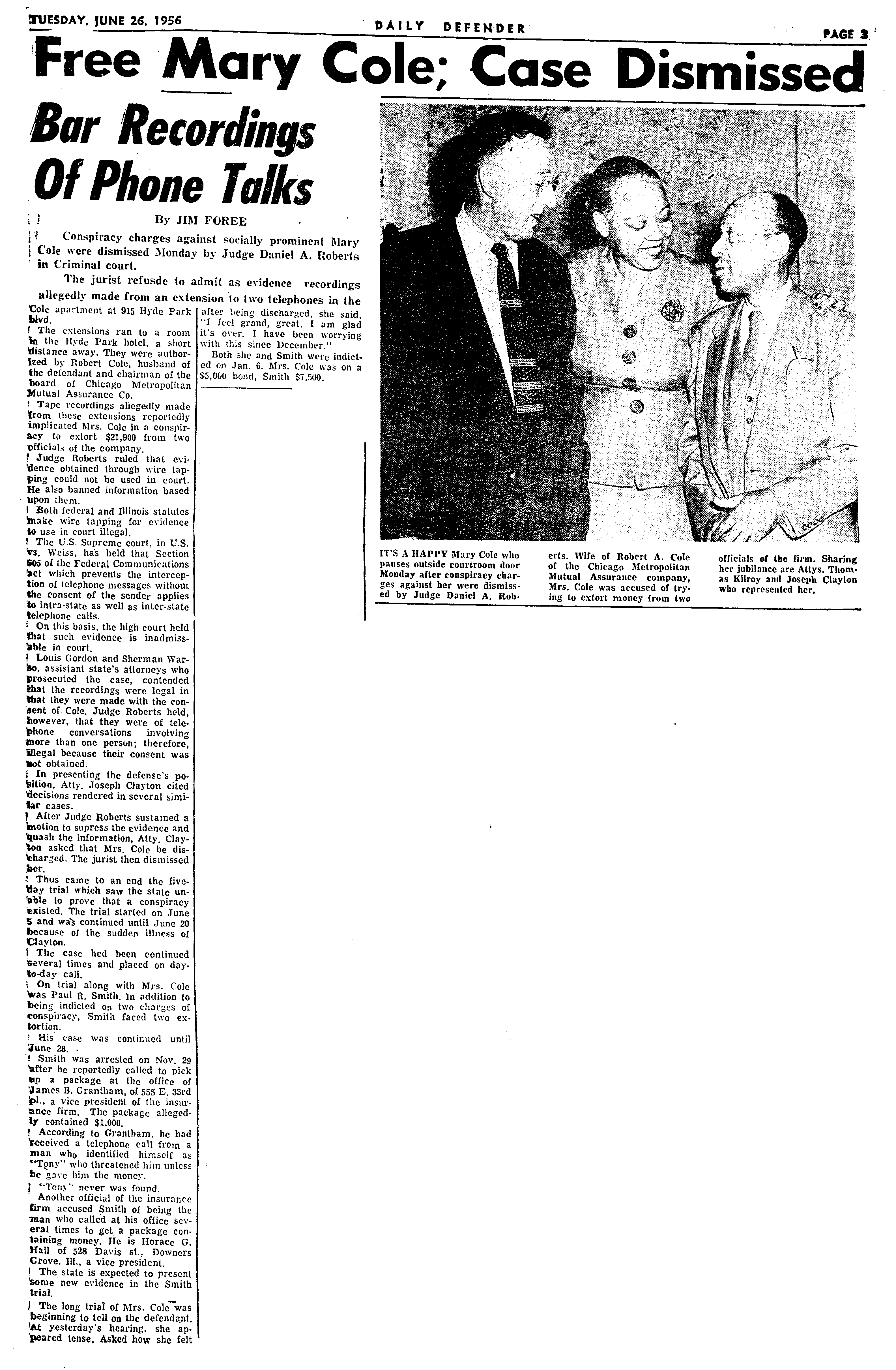

There was this whole sordid affair where CMMAC President Robert Cole's much-younger wife was charged with extortion, fraud and threatening the lives of two other employees, but I'm not especially interested in digging into it. The case was dropped in 1956, and Robert Cole died of a heart attack a month later.

Chicago Defender articles on the Mary Cole case

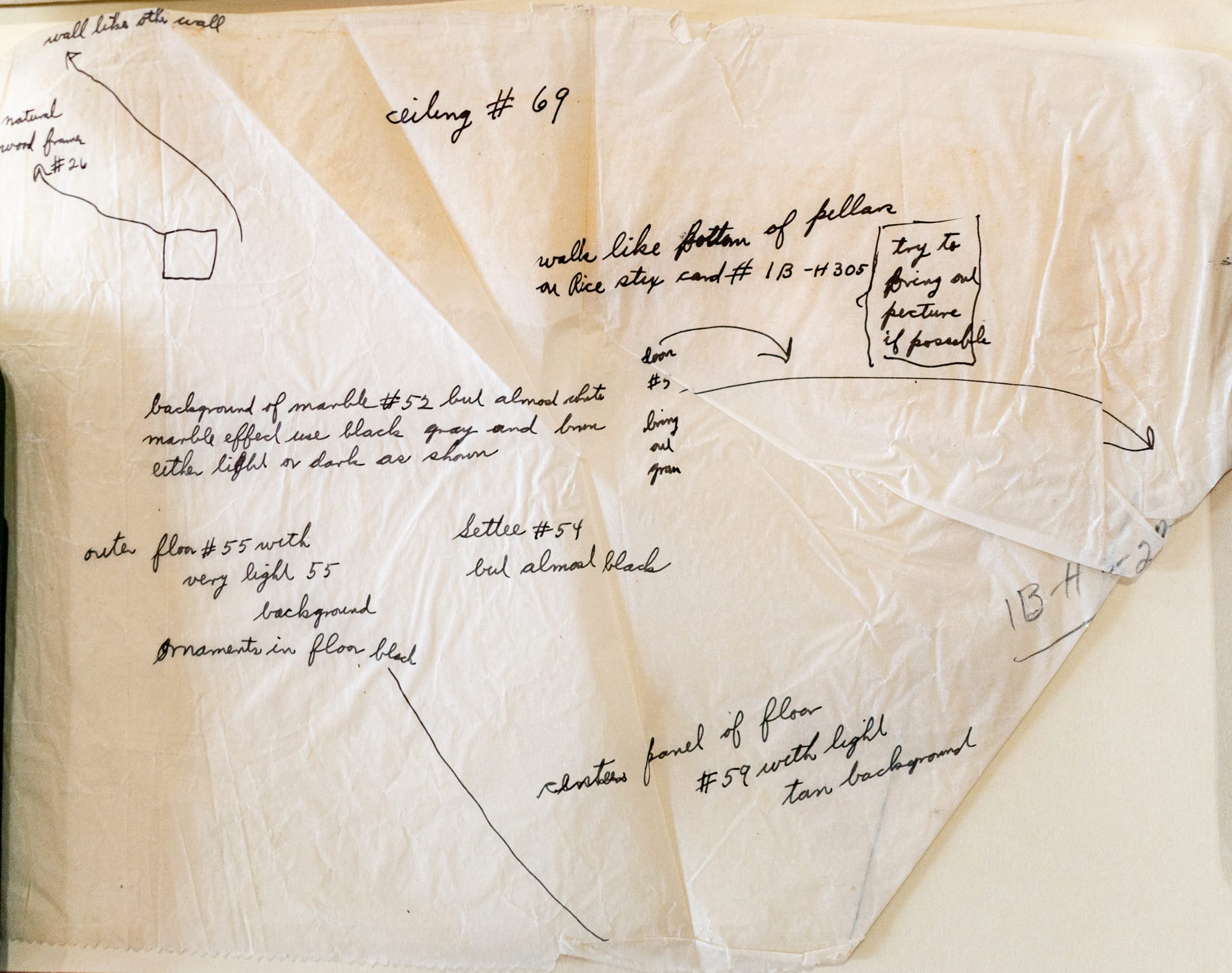

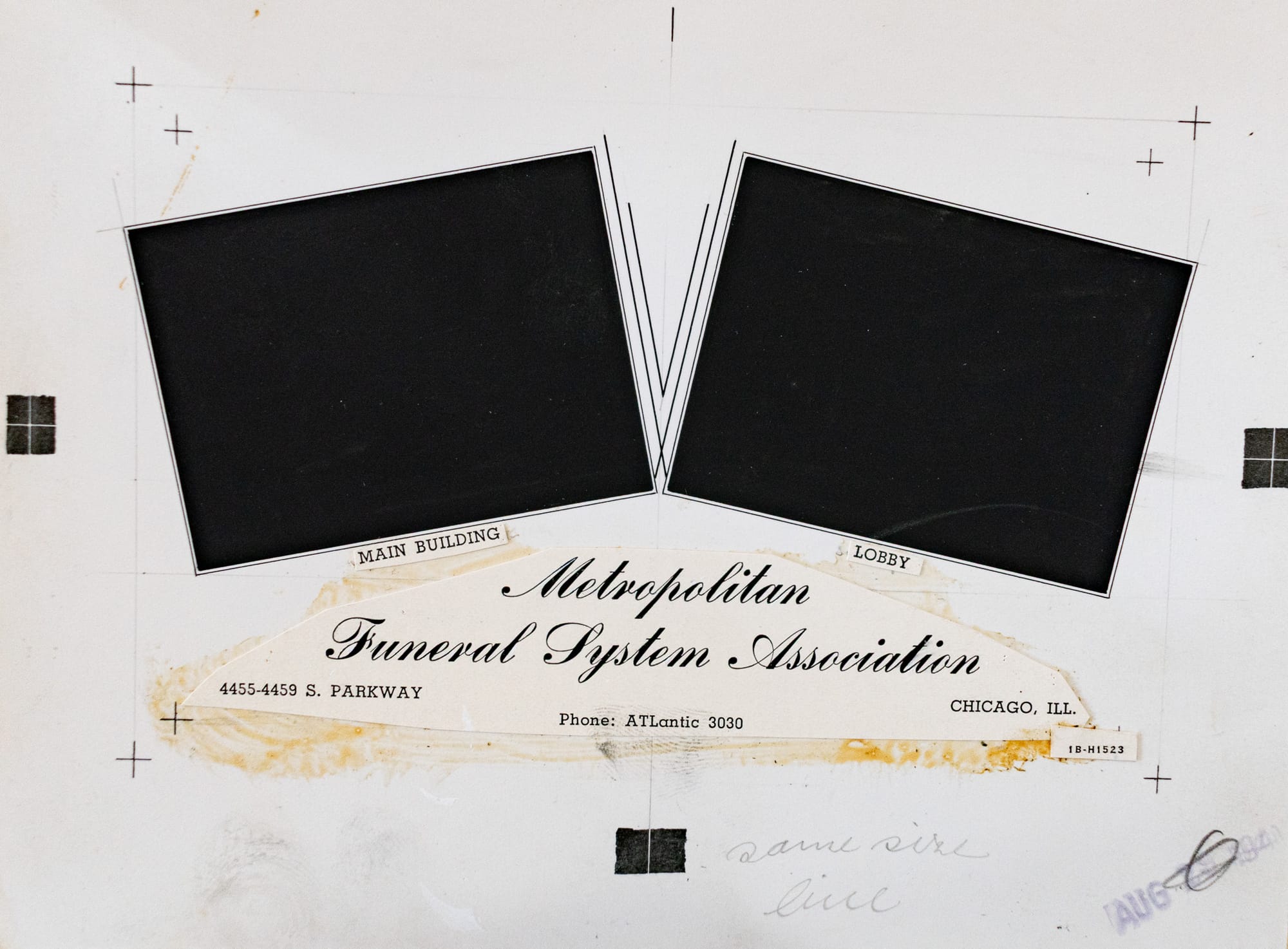

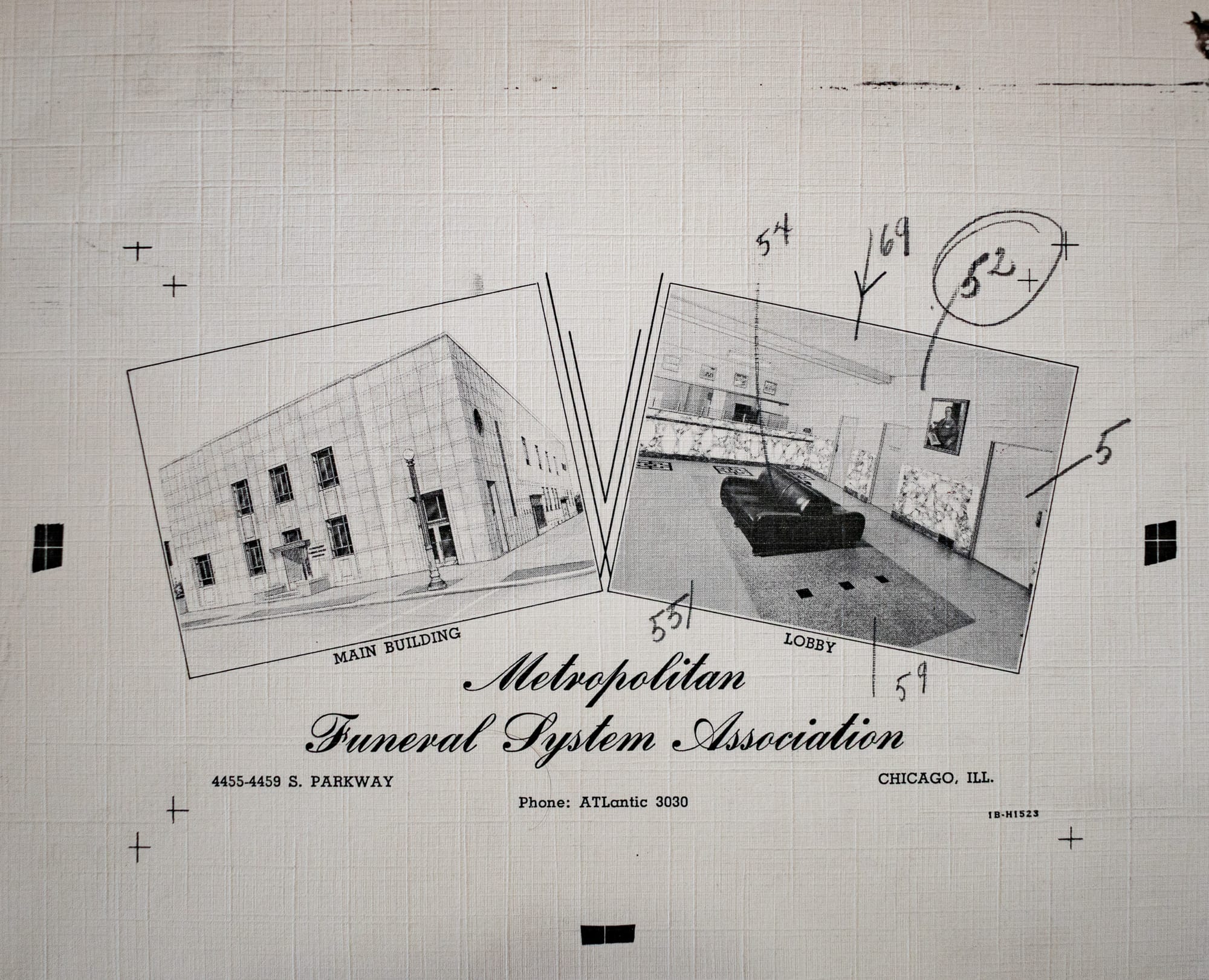

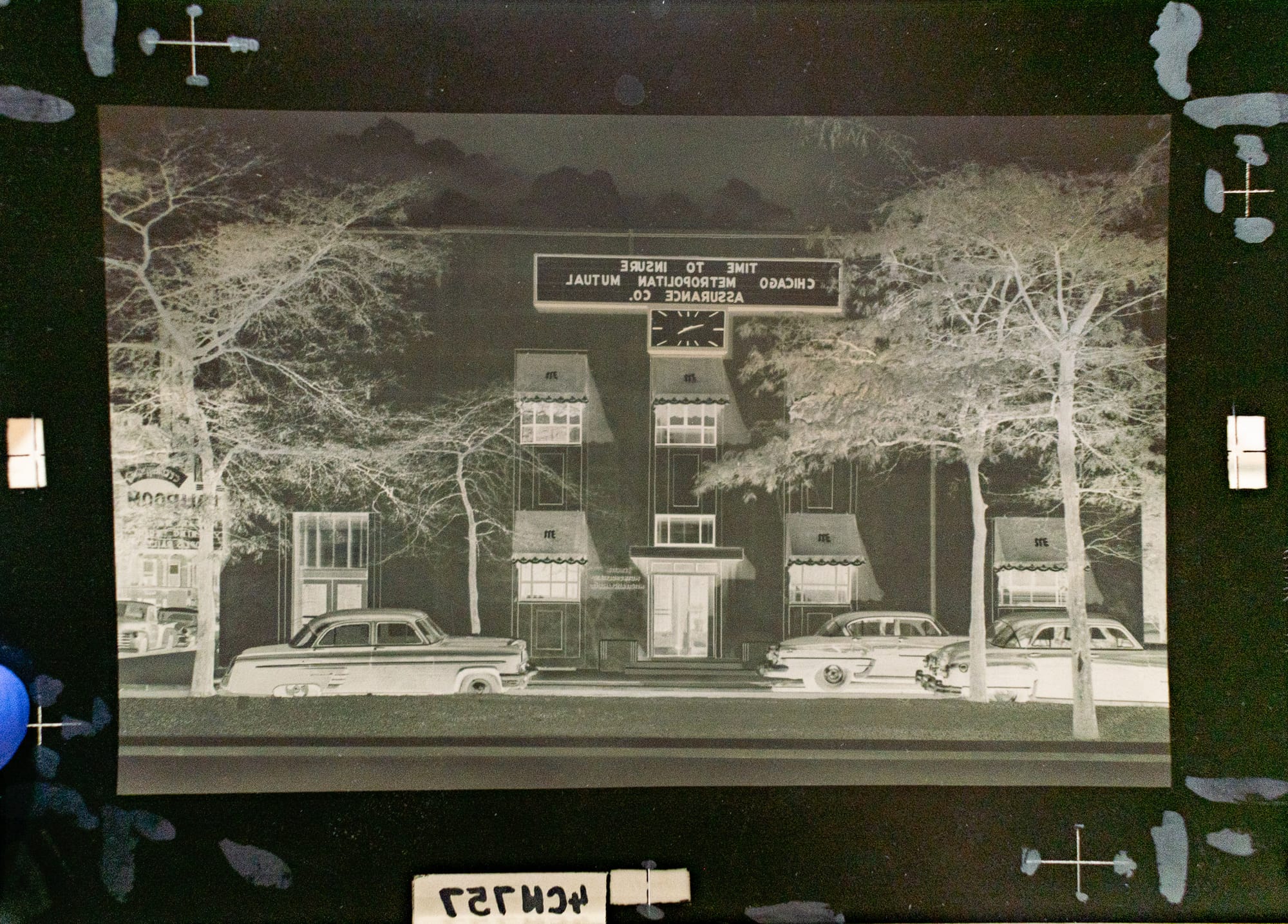

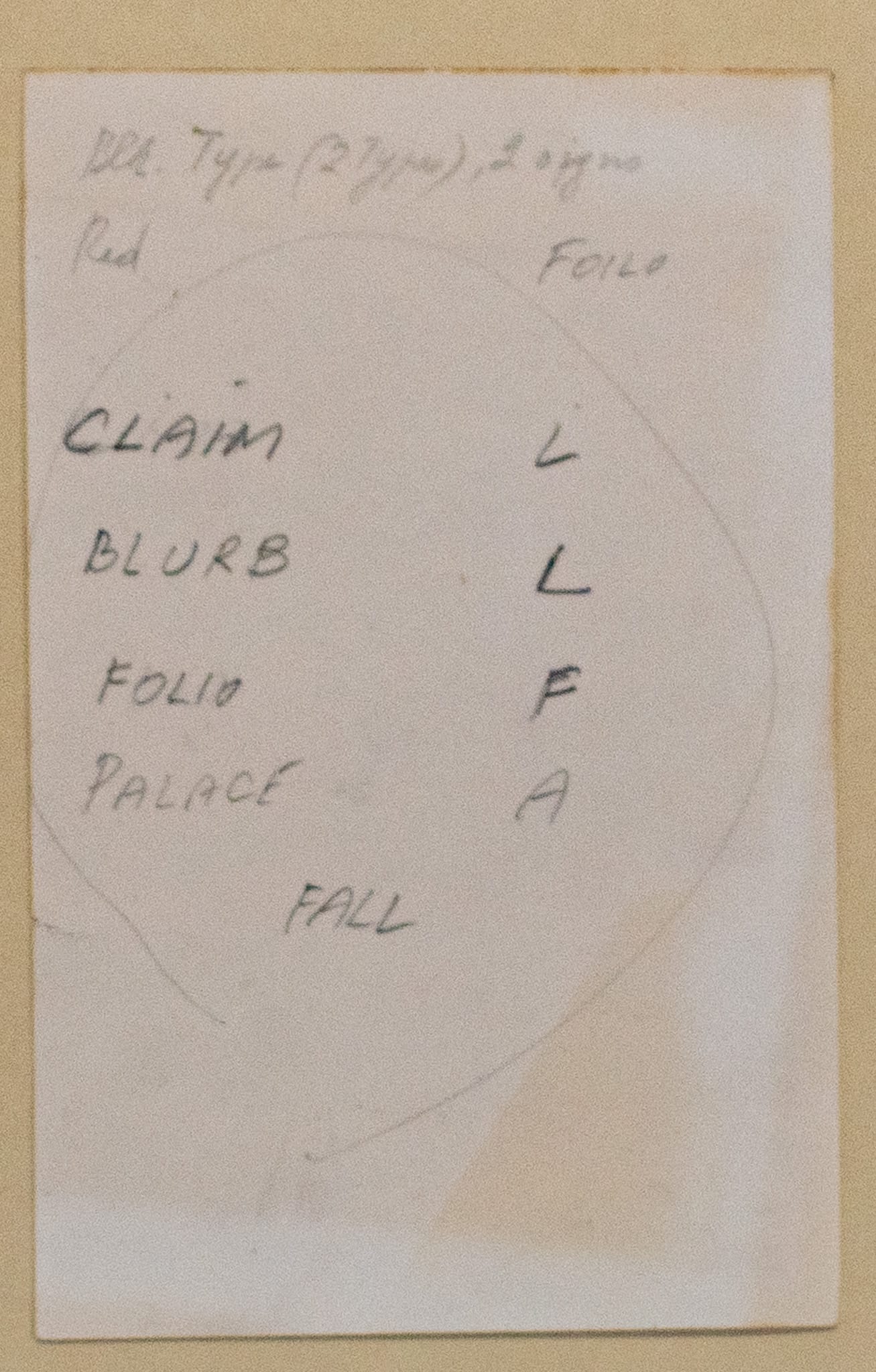

Some good stuff in the production file in the Curt Teich Postcard Archive at the Newberry Library: the retouched photo of one of the two panels, the tissue overlay with coloring and retouching instructions, and the customer design sketch.

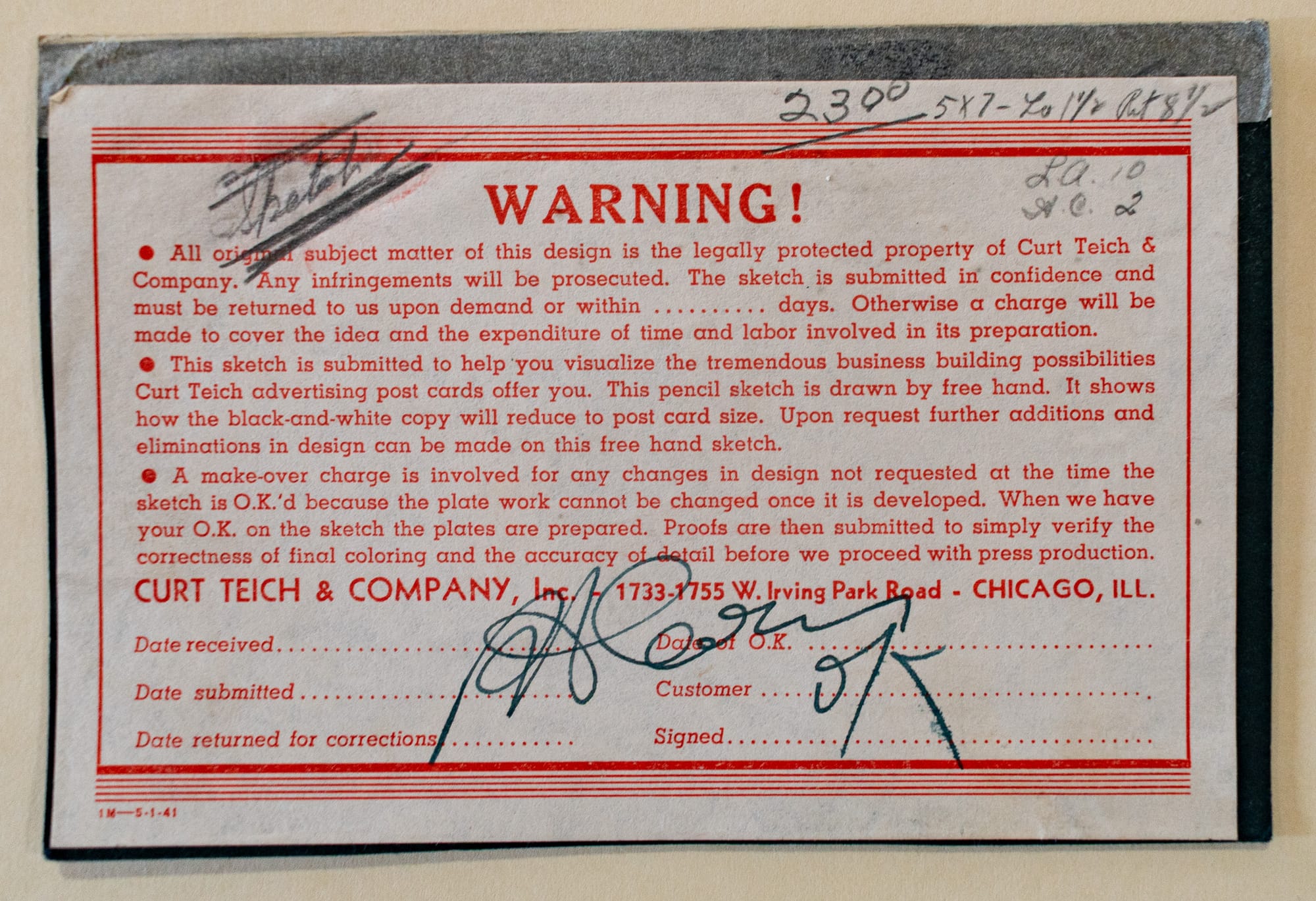

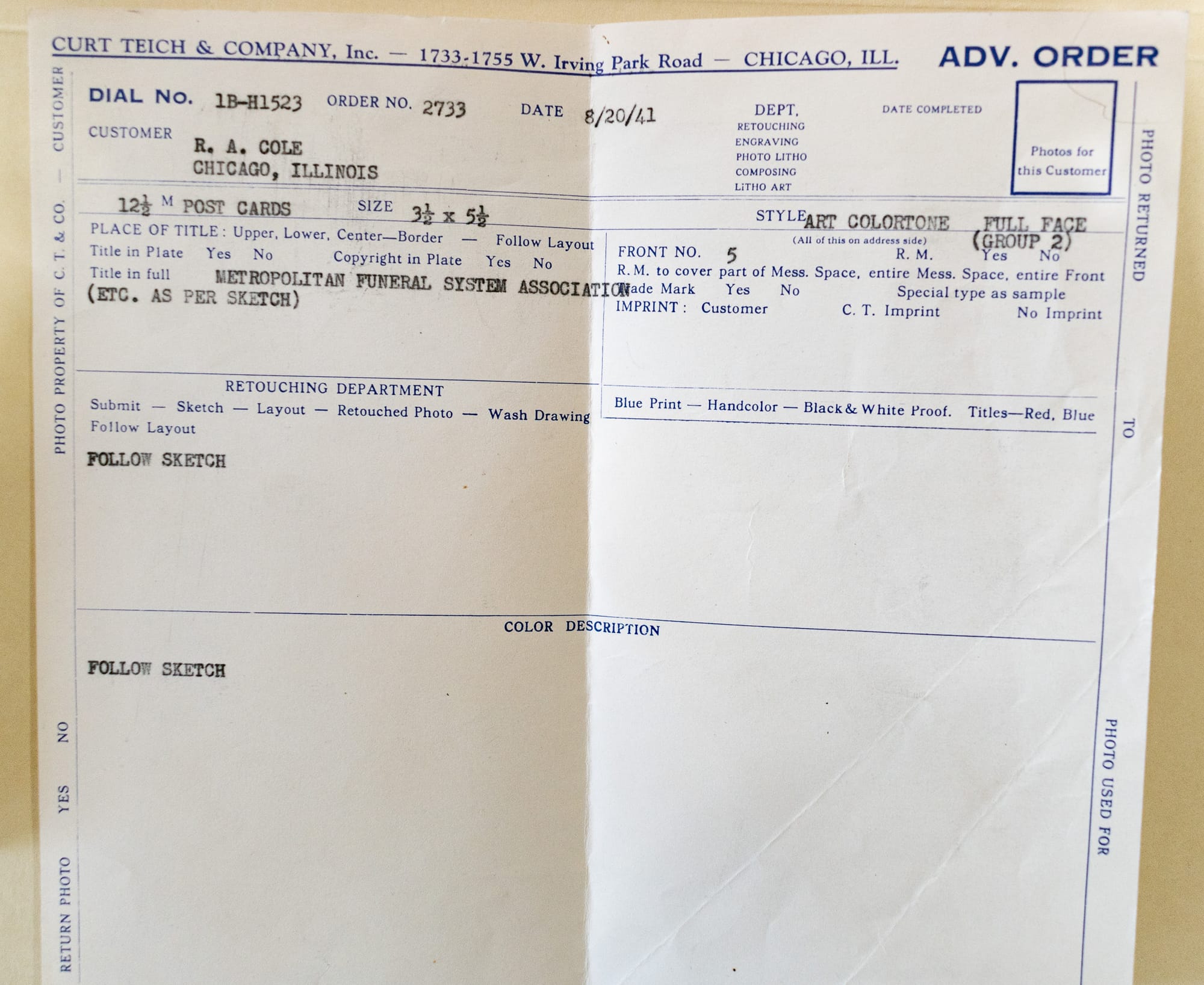

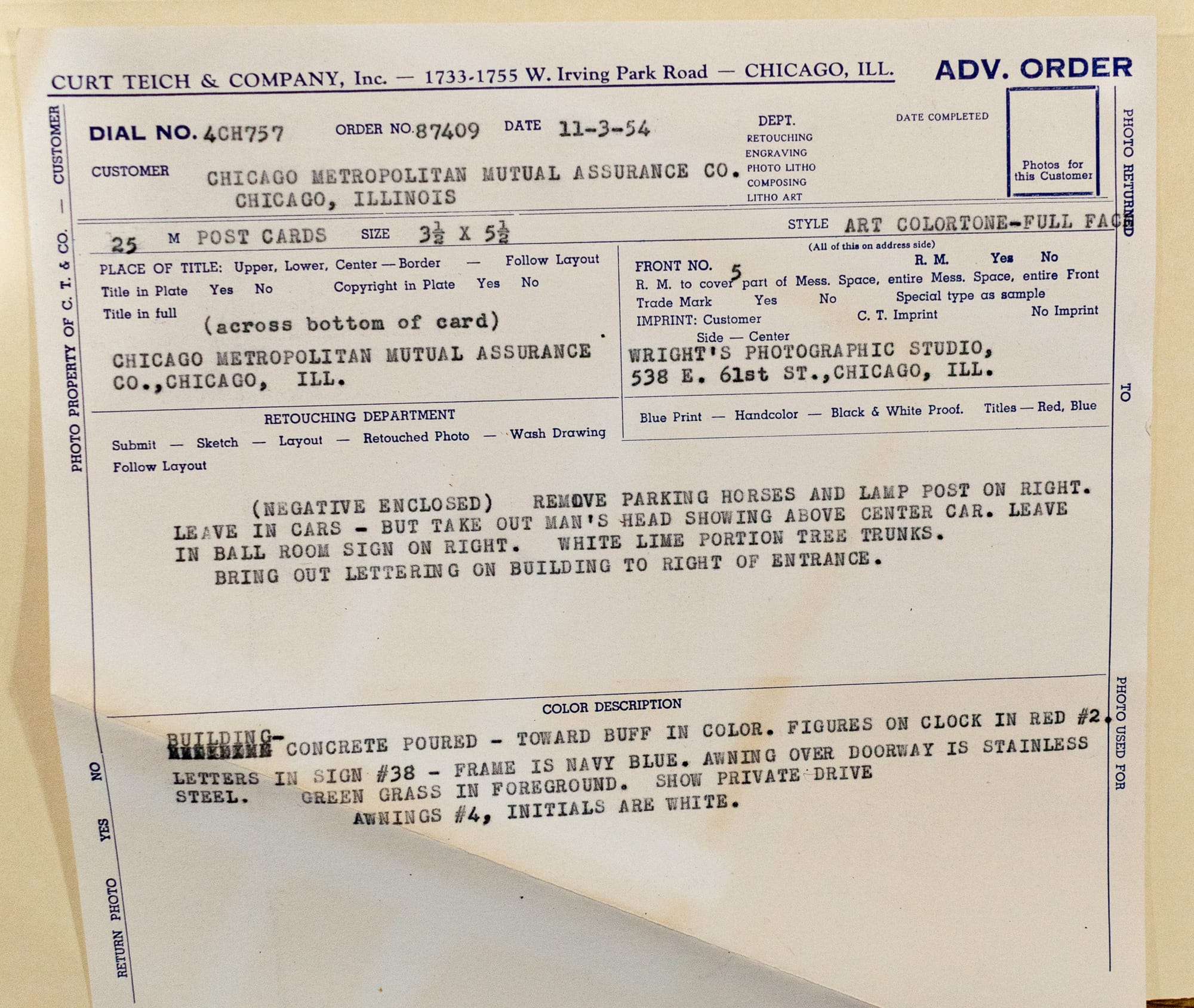

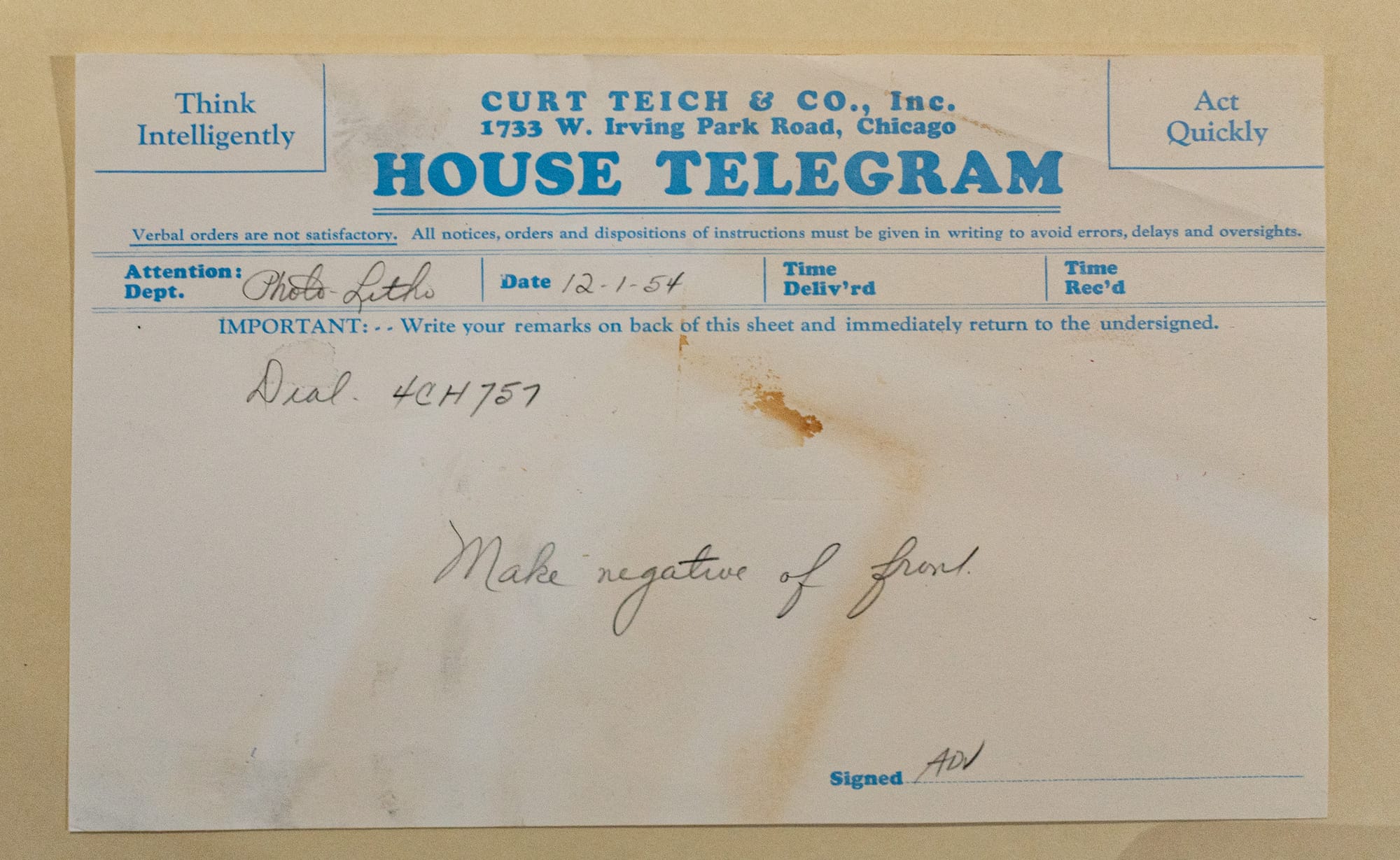

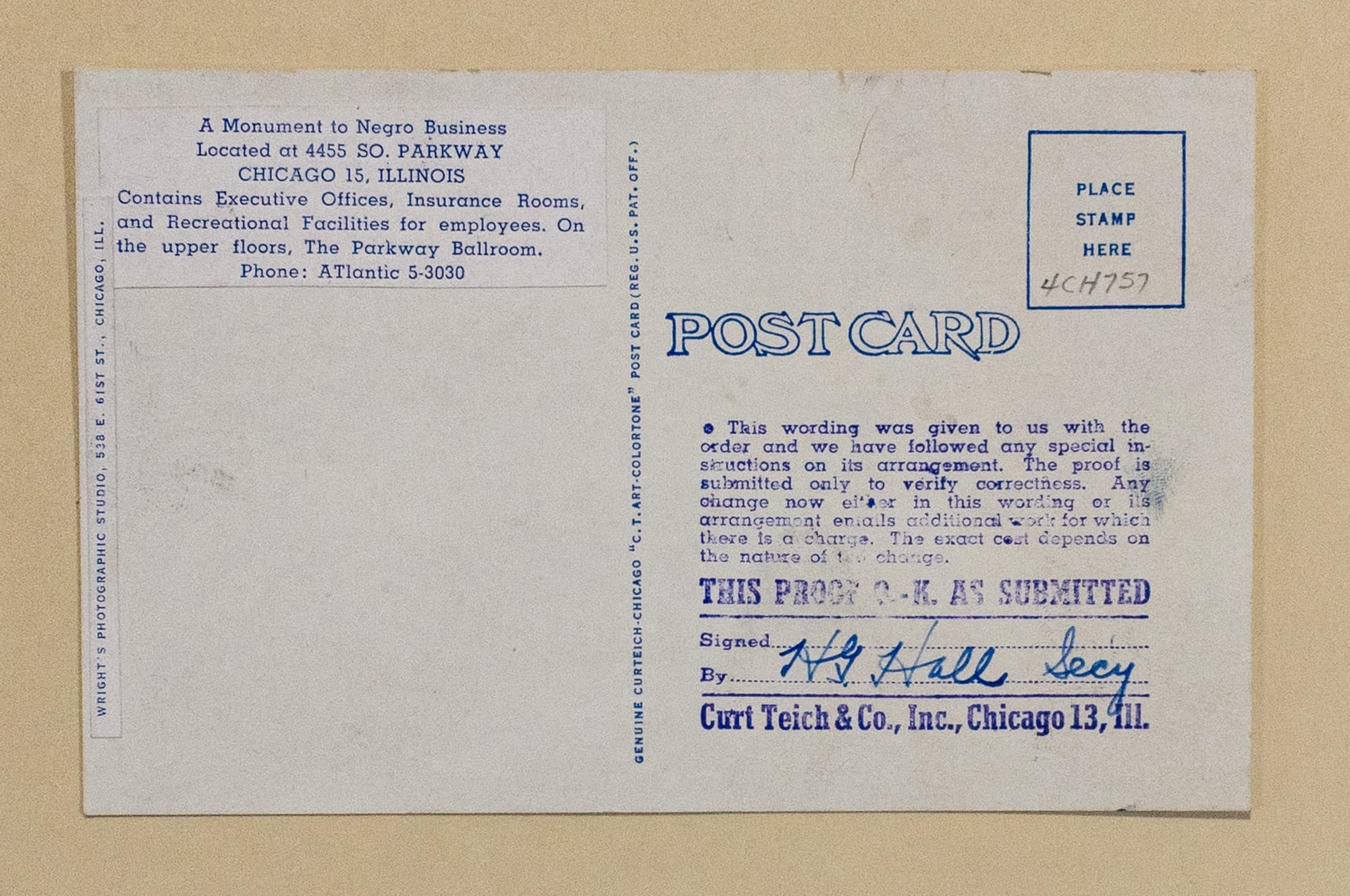

Plus the order information, some mockups, and proofs—notice that Robert A. Cole is the customer, and he even signed the proof of the verso.

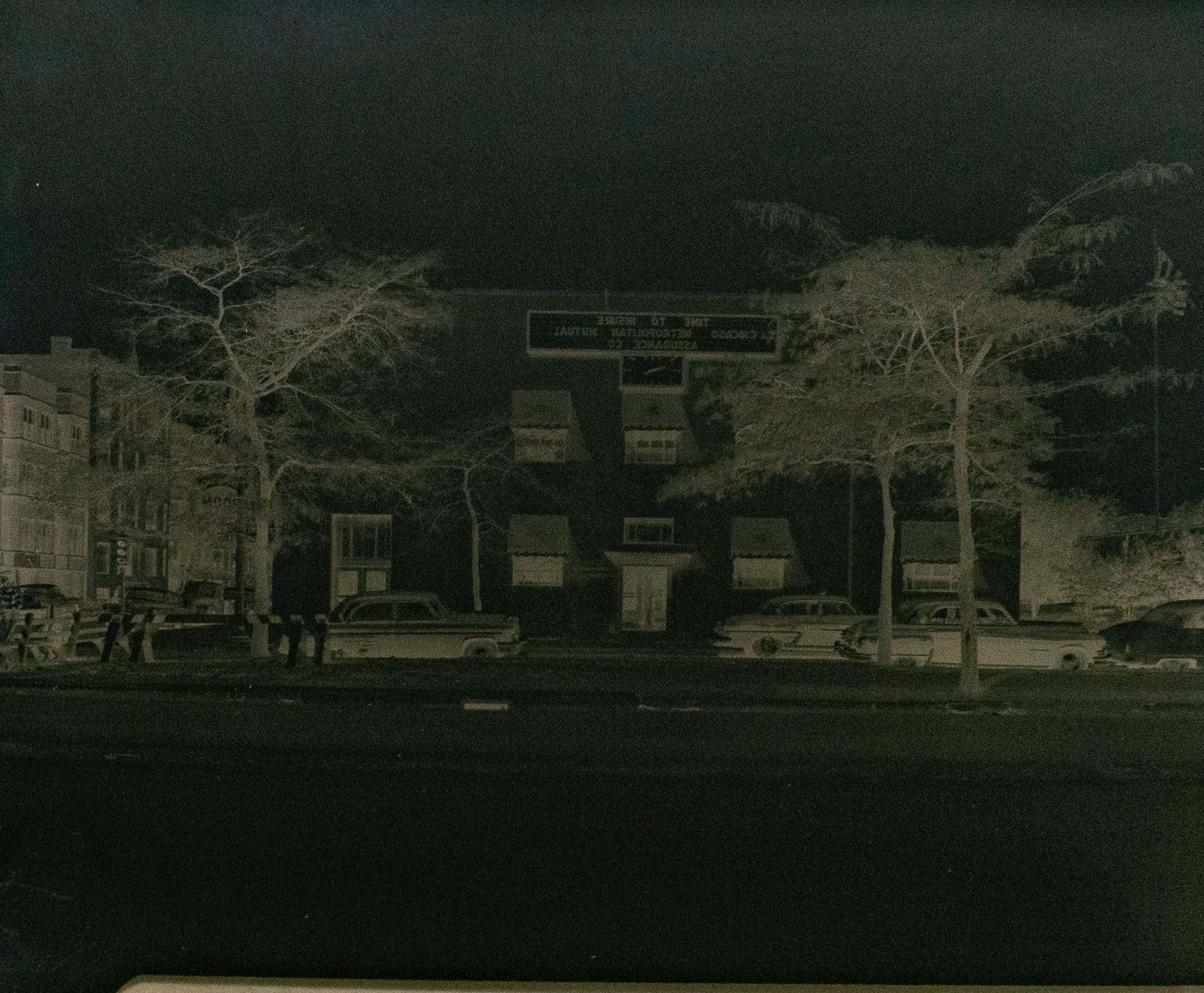

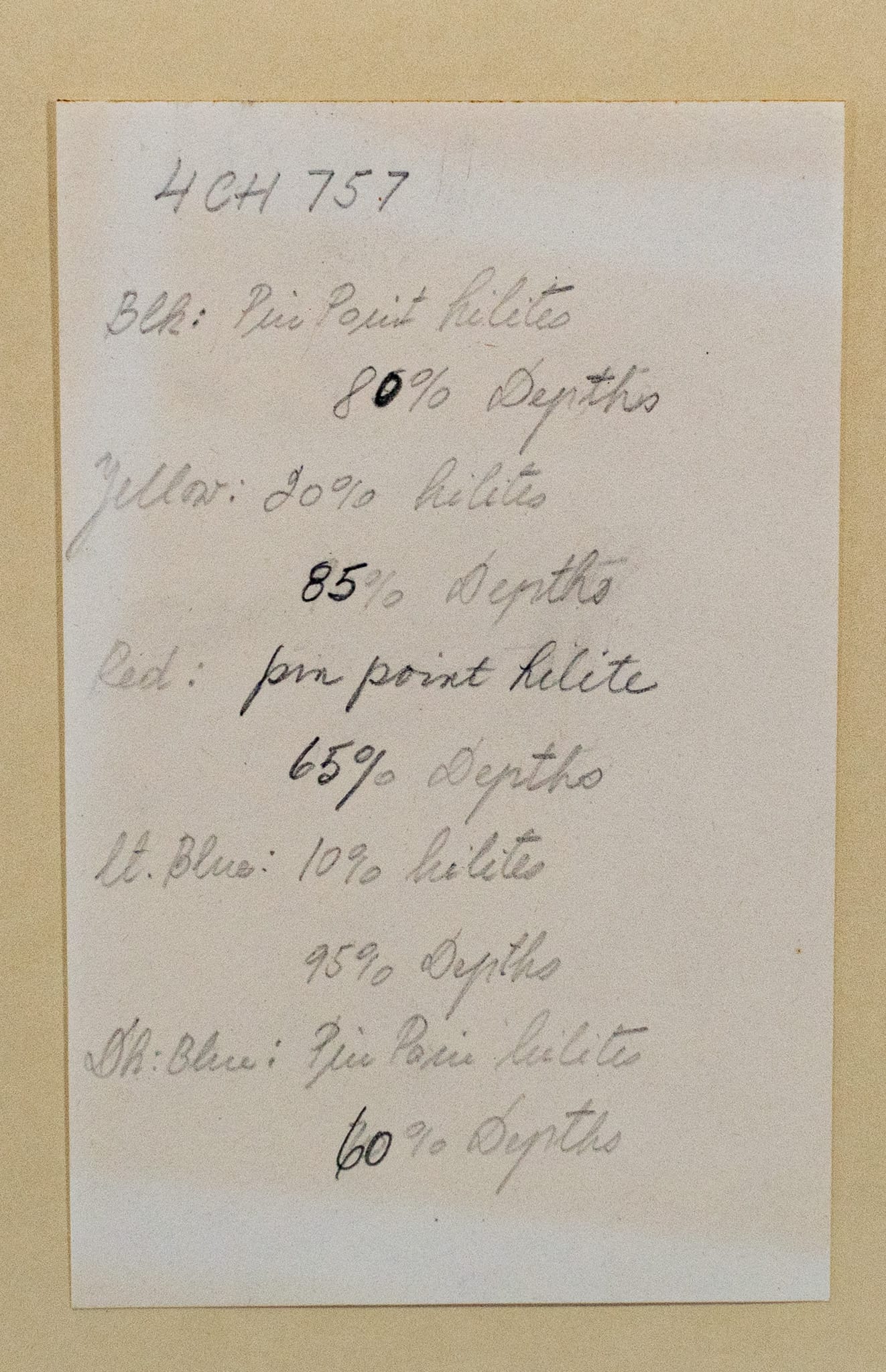

There was also some interesting stuff for the 1954 postcard in the production file at the Newberry, including the full negative, a cropped negative, and a retouched photo. Plus a ton of coloring instructions.

Member discussion: