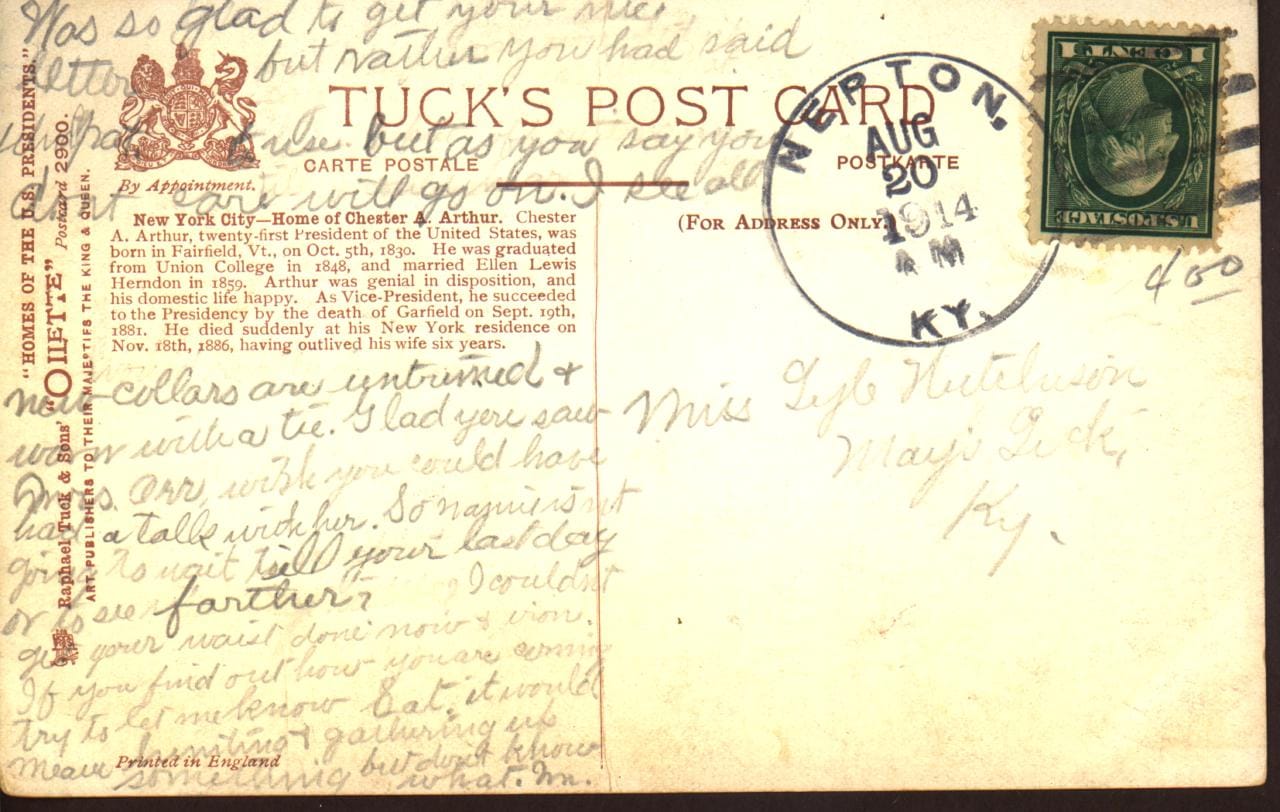

An inauguration, a dead president, and now a beloved international ingredient emporium with a specialty in South Asian & Middle Eastern spices–this is the New York I love.

And those are just the headlines: newspaperman William Randolph Hearst once owned the building and in the 1950s Jack Kerouac haunted the place–his friend, beat writer John Clellon Holmes, lived here. Though it's been here since 1944, even Kalustyan’s story has some twists and turns–opened by Armenians when this was the heart of Little Armenia, the store expanded to Indian spices as a cluster of South Asian restaurants turned this neighborhood into Curry Hill.

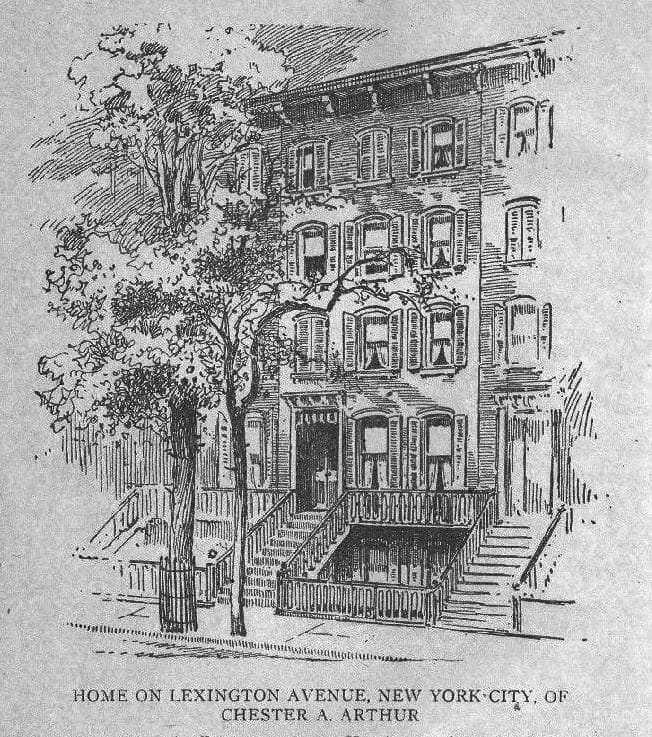

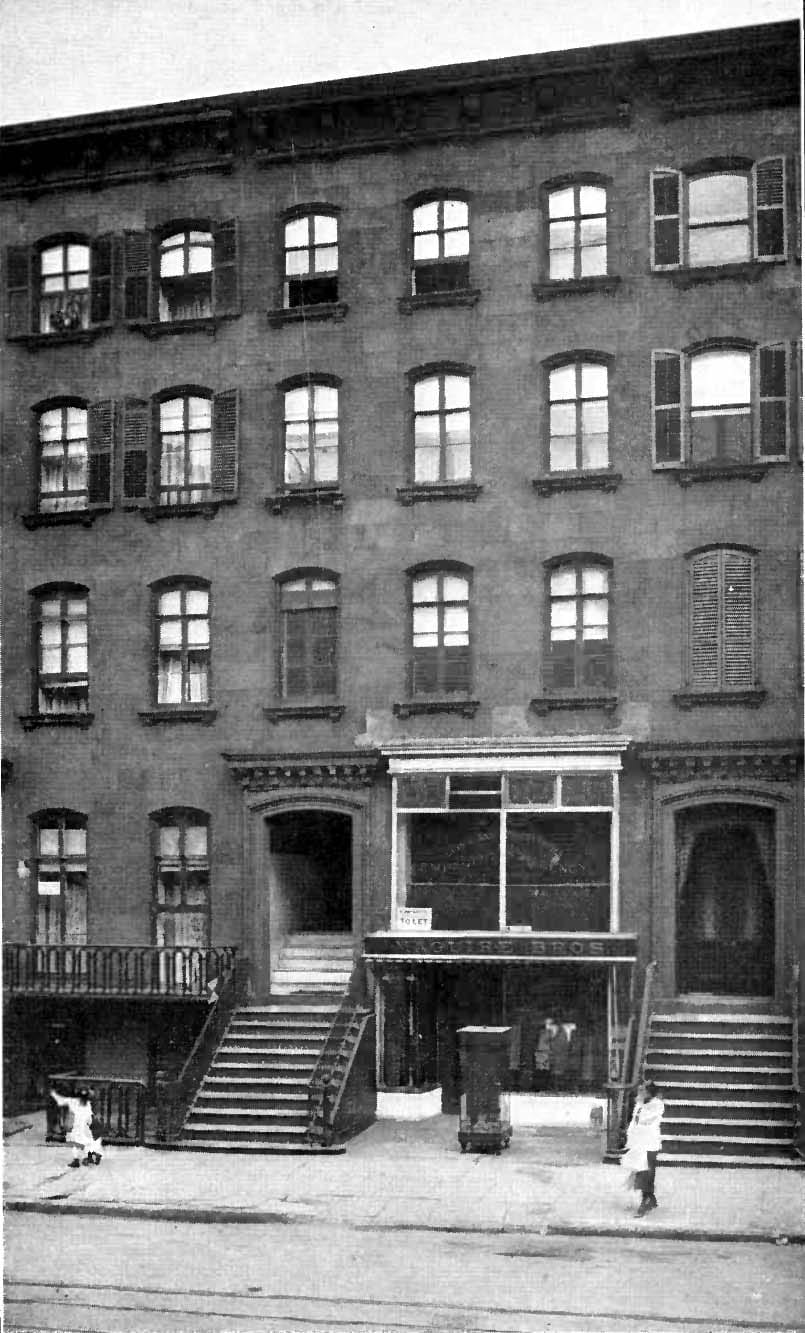

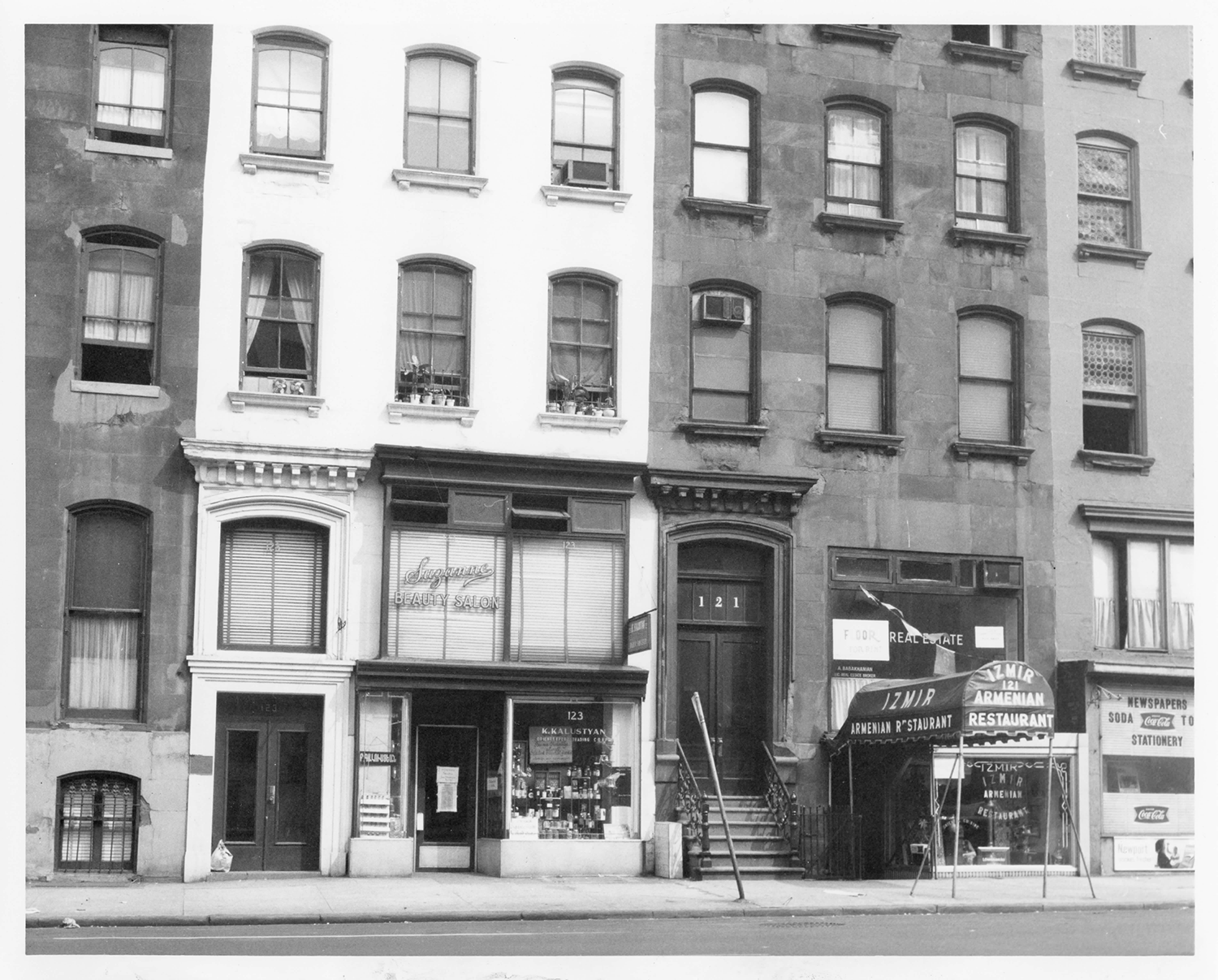

So, what's changed? Completed in 1855 as one of nine similarly-designed brownstones, surviving 170 years meant a whole lot of change. The most superficially striking change is that 123 Lexington is now faced with brick (I guess that's an upgrade–in the 1960s it was painted white). More meaningfully, under William Randolph Hearst's ownership, the first floor was turned into a garage and later a commercial space, now occupied by Kalustyan. Since the direct neighbors were basically identical, you can still see what it originally looked like (although they're somewhat altered as well). Surprisingly–since they're often the first thing to go–the cornice remains the same.

One of the unlikeliest presidents in US history, Chester A. Arthur, moved into this Lexington Ave brownstone in 1863-1864. At the time, he worked as a lawyer and a lobbyist, trading on the connections he had made as Quartermaster General of the New York State Militia during the early years of the Civil War. In the 1870s Arthur, a dandy and a key cog in Roscoe Conkling's vaunted New York patronage machine, parlayed those connections into the landing the most lucrative post in the federal government–Collector of the Port of New York.

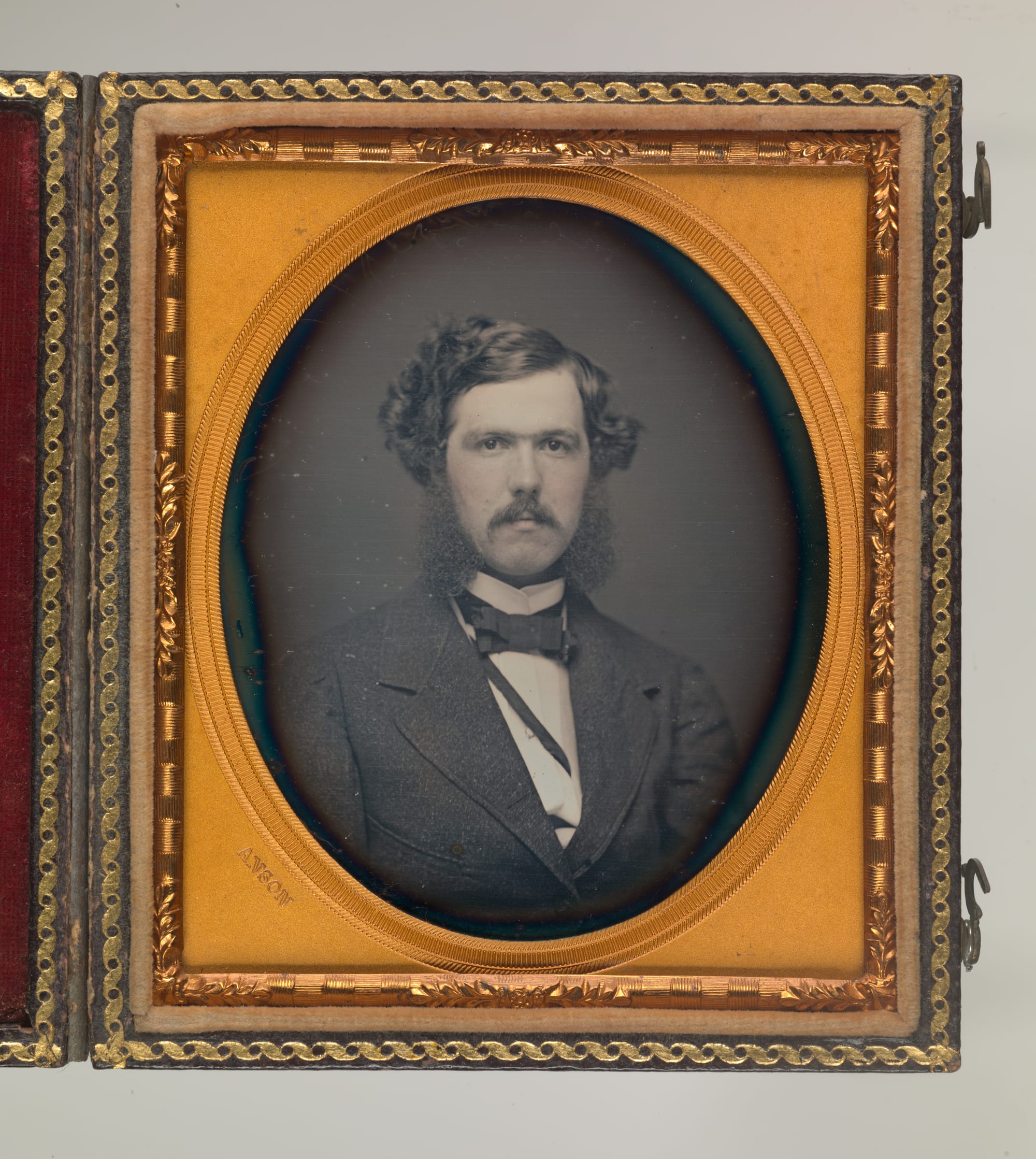

1800s sketch of 123 Lexington, Wikimedia Commons | 1858 daguerrotype of Chester A. Arthur, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

With the spoils system still powerful, that meant Arthur controlled thousands of jobs on behalf of Conkling's "Stalwart" wing of the Republican Party–the rowhouse at 123 Lexington became a sort of Stalwart HQ, regularly visited by Conkling and his peers. The Port Collector job financed a lavish lifestyle for Arthur and his family here until corruption scandals gave President Rutherford B. Hayes–a Republican from a competing faction, the Half-Breeds–an opening to fire Arthur in 1878.

You'd think that would have ended his political career, but Chester A. Arthur soon fell ass backwards into the Vice Presidency.

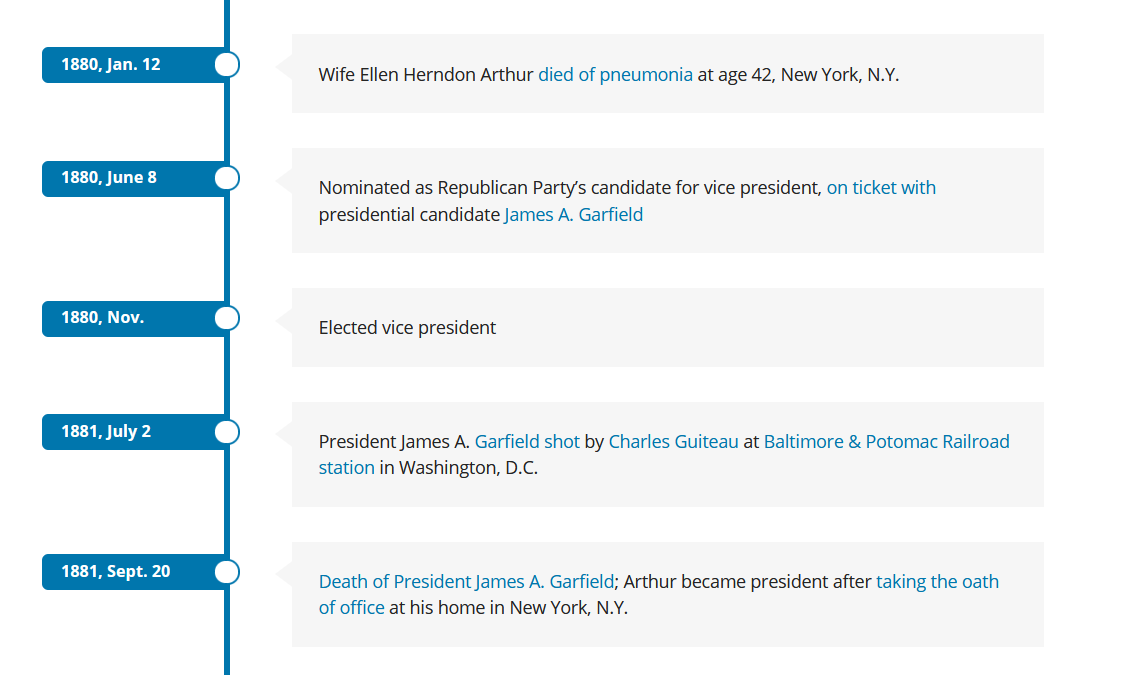

January, 1880 kicked off one of the craziest two years anyone has ever had. First, in January, Arthur's wife died–a sad start for a mildly dishonored machine politician. In June of that year Half-Breed James Garfield won the Republican nomination for president, and to bridge the rift with the Stalwart faction he offered Arthur, still carrying a whiff of disgrace, the VP role. Conkling instructed his stooge to refuse–confident Garfield was going to lose the election–but Arthur suddenly grew a spine and, unexpectedly, accepted. In November 1880, Garfield and Arthur, unexpectedly, won. On March 4th, 1881, Chet Arthur–as his friends called him–was sworn in as Vice President of the United States of America. In a bizarre collision between the spoils system and mental illness, on July 2nd that year crazed job seeker Charles Guiteau shot President Garfield.

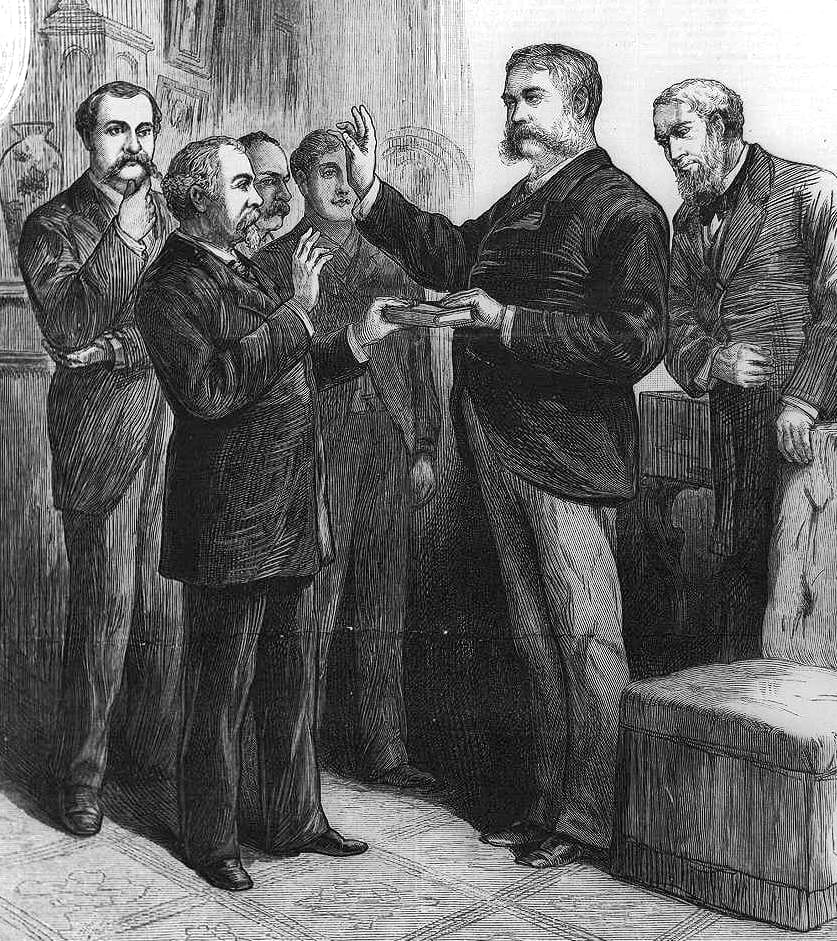

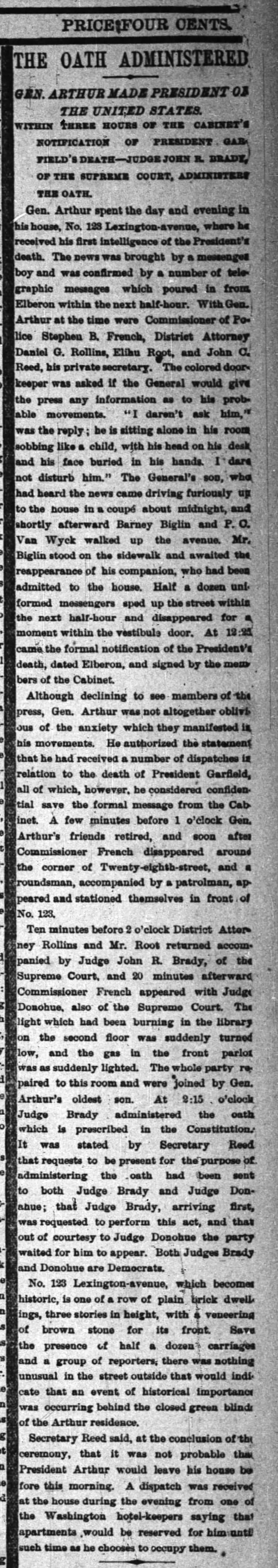

Already an unlikely VP, Arthur didn’t want to be seen as too eager to become president while Garfield still lived, so he loitered awkwardly at his home here for weeks as President Garfield slowly died. After two months of deeply questionable medical care, Garfield died on September 20th, 1881, and Arthur was hastily inaugurated here. Yup–this spice shop is the only extant building in New York where a president was inaugurated (the Federal Hall where George Washington was inaugurated was torn down and replaced with a different Federal Hall).

Sketch of Arthur's inauguration at 123 Lexington Ave, Wikimedia Commons | 1881 New York Times article about the administration of the oath | 1882 article about Arthur moving to the White House and out of 123 Lexington Ave.

From a tainted has-been of the party machine to a widowed president in less than two years, succeeding the second-shortest presidency in US history–the 21st president of the United States, Chester A. Arthur. Or, as his friends and enemies called him, “Chet Arthur president of the United States! Good God!” and “His Accidency".

Arthur was a mediocre, forgettable president, but he did one admirable thing–it took a corrupt creature of the spoils system to kill it, which Arthur did when he signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act in 1883, which required federal government jobs be awarded on merit.

An accidental president and a bit of a weird cipher, Arthur burned most of his papers in this building after his term ended. Suffering from Bright's Disease, two years after leaving the White House Chester A. Arthur passed away in his bedroom on the second floor here in 1886.

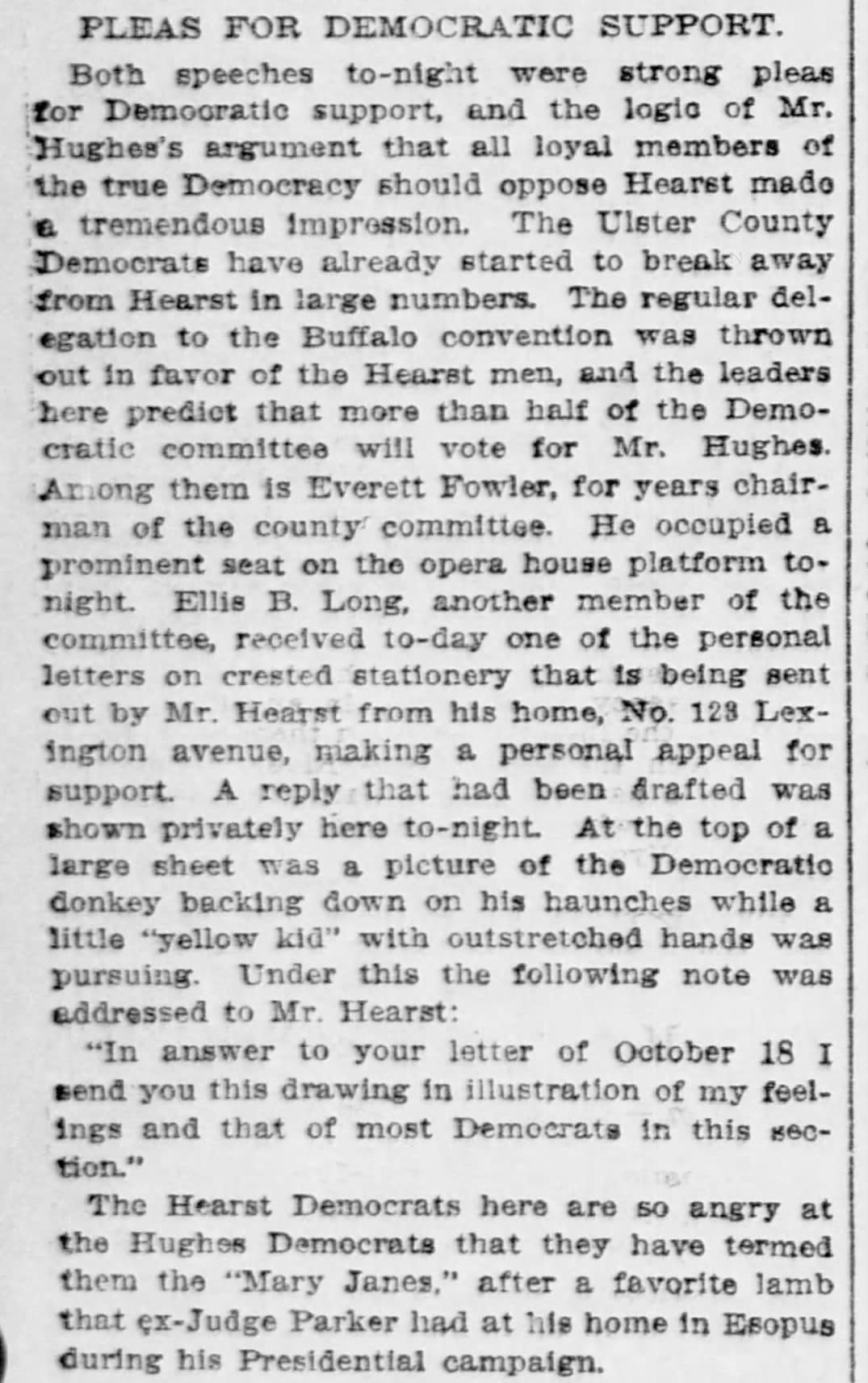

You would think an inauguration and a president's death would be enough narrative for one building, but it's New York. In 1902, newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst bought the former president's home. There's a split on whether or not he ever lived here: multiple biographies and contemporary newspaper articles suggest he did, but the New York Buildings Department and the Landmarks Preservation Commission describe suggestions that Hearst lived here as "disproven" (they do not dispute that he owned the building, however). Hearst also owned the building two doors south, 119 Lexington Ave., which is where some of the confusion stems from.

1902 articles about Hearst buying Arthur's old house | Nostalgic 1904 article that uses Hearst's changes to Arthur's home as an example of how "New York sweeps about its well-known landmarks" | Building permit notice, 1902 | Articles about Hearst's plans to turn the building into mixed-use commercial and apartments, 1910

Personally, my impression is that Hearst mainly used it as a guesthouse for his friends Jack Follansbee and Arthur Brisbane, as well as storage for his various collections, but that he may have lived here with his friends for a bit shortly after buying it, when he was a bachelor. He likely moved after marrying his (MUCH) younger wife Millicent (Will Hearst started to pursue her when she was 14 and he was 34). Regardless, the newspaper publisher–whose life inspired Citizen Kane–did live on this block of Lexington Avenue, in a home he called the Shanty, and he did own this building.

One person who visited the building when Hearst owned it recalls it as filled with “a wonderfully painted and gilded Egyptian mummy case standing on end under glass; there a complete suit of ancient German armor. On a pianola stood a gilded bronze statuette of Caesar crossing the Rubicon and one of Napoleon as First Consul. In a corner gleamed Fremiet's golden St. George and the Dragon and under a window a beautiful porcelain Eve with Cain and Abel, as infants, playing at her knee". Around 1910 Hearst hired eventually architect James C. Green to convert the first floor to retail with apartments above.

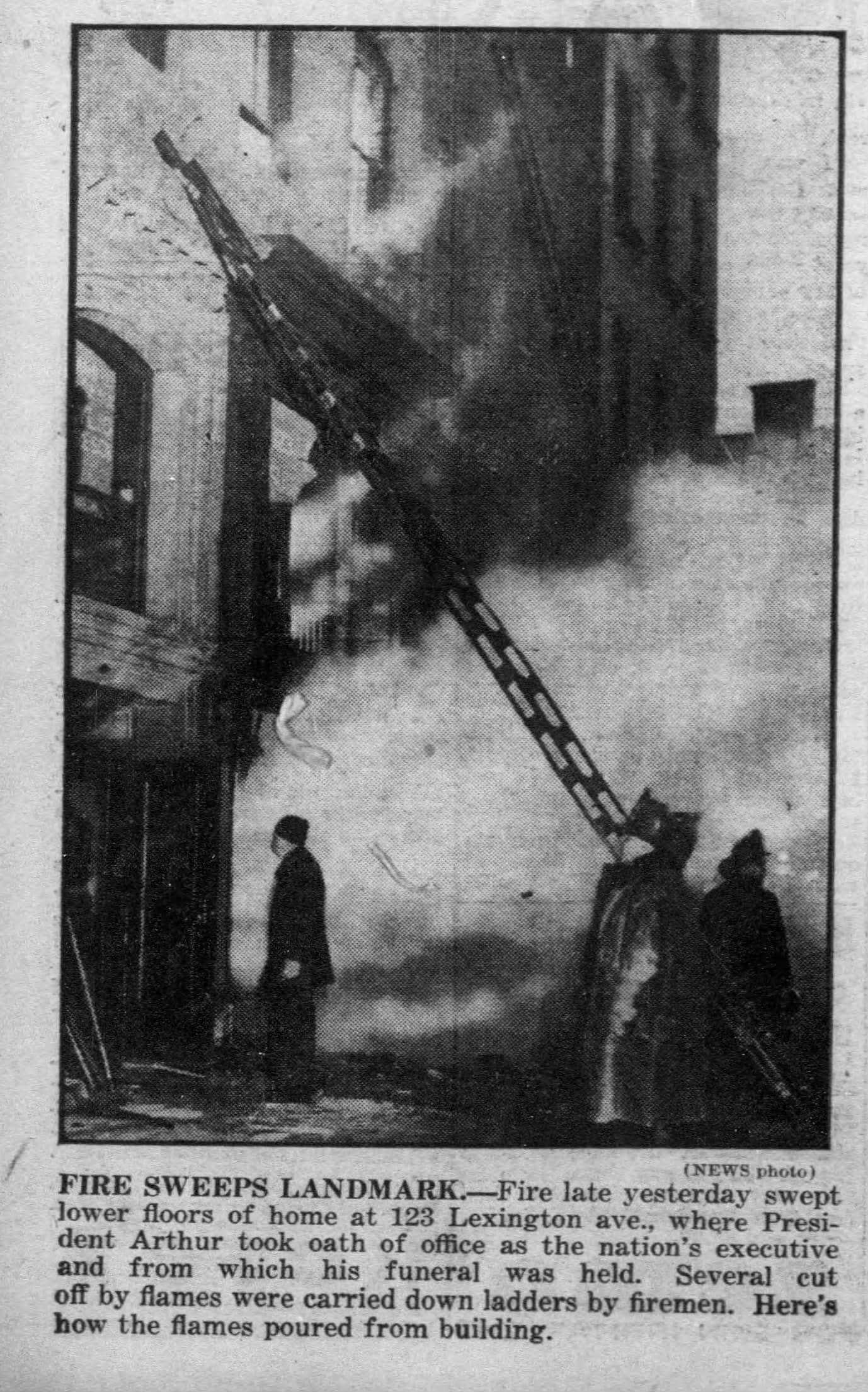

1914, Wikimedia Commons | 1925, Brown Brothers, NYPL | 1927 fire | ~1940 New York Tax Department Photograph, New York City Municipal Archives

Despite being greatly altered from Arthur’s time, the building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965. The documentation is quite funny, as the National Parks Service felt they needed to honor something related to Chester A. Arthur's life, but there were no good options for the National Park Service. Growing up the Arthurs had moved regularly, and so most of the homes connected to his childhood had been demolished or moved.

Whereas in the case of 123 Lexington, where Arthur lived for more than 20 years, by the 1960s “the house is not too well maintained, however, it is not in a deplorable condition”. However, “(the owner) is not too happy about putting any money in the preservation of the building since she feels the home is in a low graded area and may be demolished under an urban renewal project in the future". Basically, it was heavily altered but still the best of a bad bunch.

By that point Armenian immigrants had opened a store on the first floor selling Middle Eastern foods. Kalustyan's opened in 1944, when this area was a hub of the Armenian community. As the Indian presence in the neighborhood grew in the 60s and 70s, Kalustyan's expanded to Indian spices–and the store grew along with it. Today it uses the first two floors as well as part of the building next door, with apartments above.

1964 National Park Service photographs, National Register of Historic Places Collection

While 123 Lexington is a National Historic Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it is not a New York City landmark. After languishing on the Landmarks Preservation Commission docket for years, it was finally rejected in 2016, with the Commission determining it was too altered from its original state.

City landmark or not, this feels like a quintessential example of the good parts of New York. Home to a president, sure, but without a suffocating preciousness and historicism–it's still part of a living city, and so hundreds of other people have also made this building their home, including a business that's made just as much an impact on the city as Chester A. Arthur ever did.

Production Files

Further reading:

- The NRHP registration form

- The LPC research file

- Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur by Thomas C. Reeves

- The Chief: the Life of William Randolph Hearst by David Nasaw

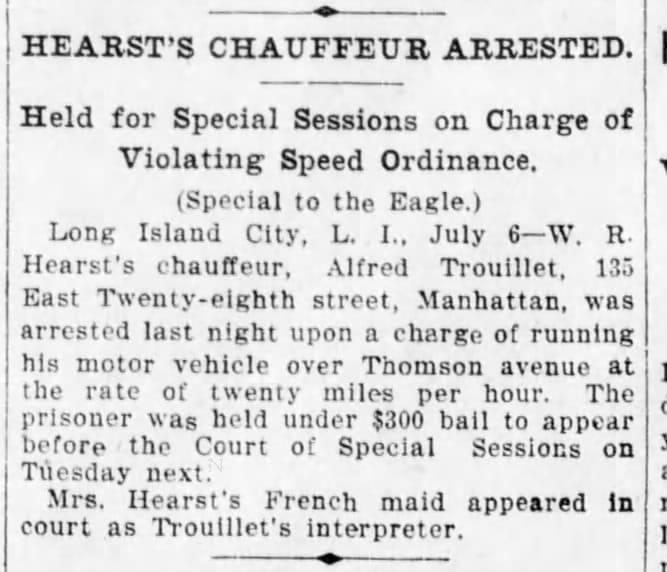

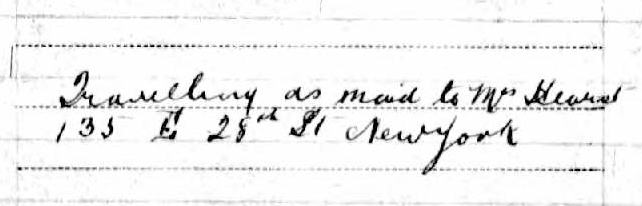

Some varying bits of evidence in contemporary sources of William Randolph Hearst's New York address from 1902-1909, including multiple political races where his address is listed at 135 E. 28th St (which is the same building as 119 Lexington Ave.), as well as a passenger manifest from 1905 where someone says there are going to work as a maid at Hearst's residence at 135 E. 28th.

Seriously, what an absurd two-year stretch here.

Member discussion: