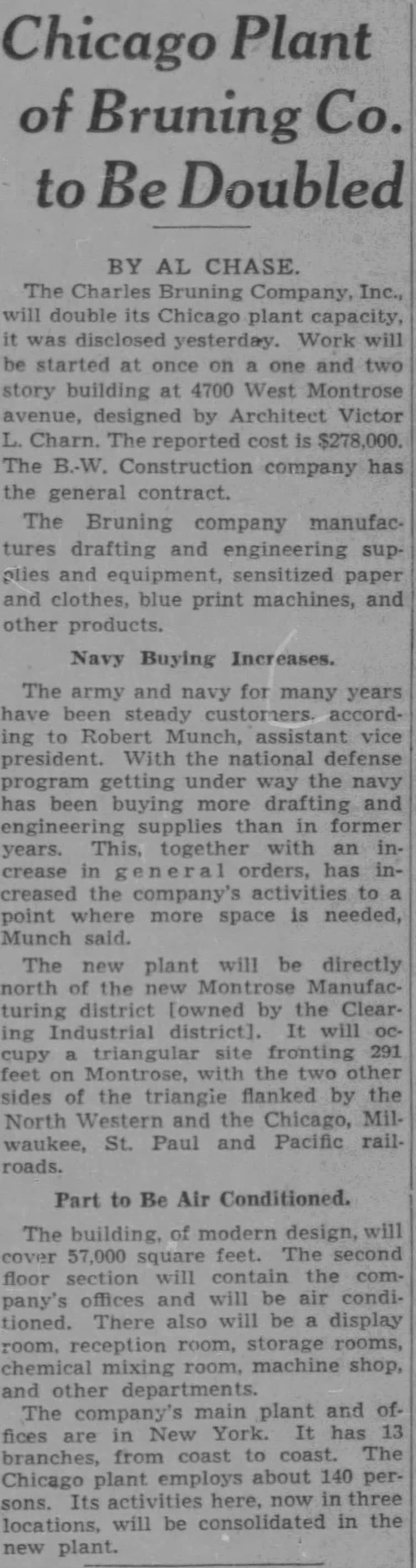

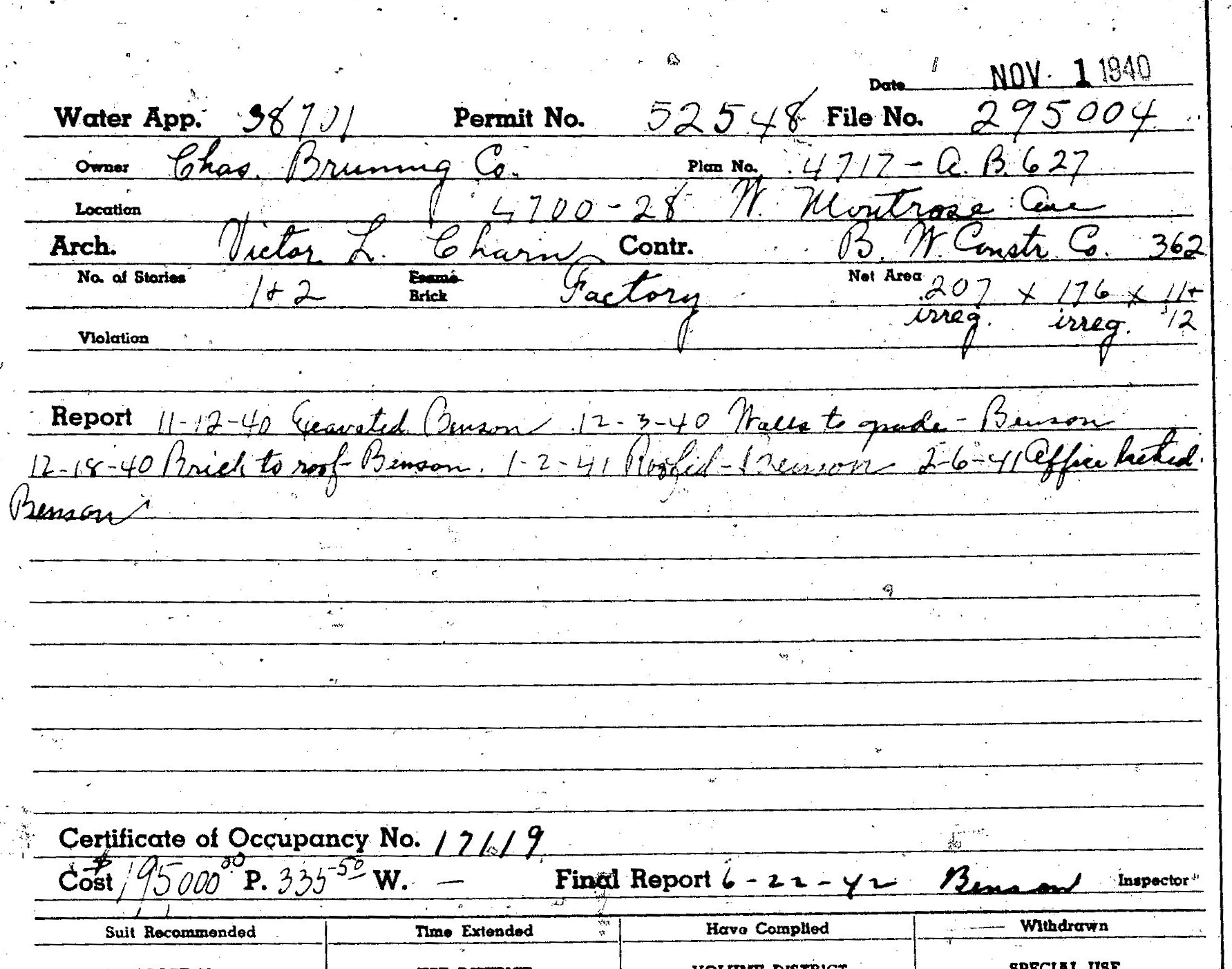

The building that blueprints built, even more literally than usual–the Charles Bruning Co. manufactured blueprint paper, drafting equipment, and associated machinery. Growing rapidly as the US came out of the Great Depression, Charles Bruning Co. commissioned architect Victor L. Charn to design a factory consolidating their production in Chicago. Nestled between two rail lines, this gorgeous Art Moderne factory opened in 1941.

So, what's changed? The CTA switched the Montrose Avenue streetcar to trolleybuses in 1948, paving over those tracks (eventually). Someone punched a loading dock next to the front entrance–that used to be the office section–and the landscaping was ripped up to accommodate deliveries and parking. That chimney may have been airbrushed out. Otherwise, though, this is still a splendid example of art moderne architecture--curvy and horizontal, with neat ribbon windows, warm brick, and lively terracotta highlights. Good shit.

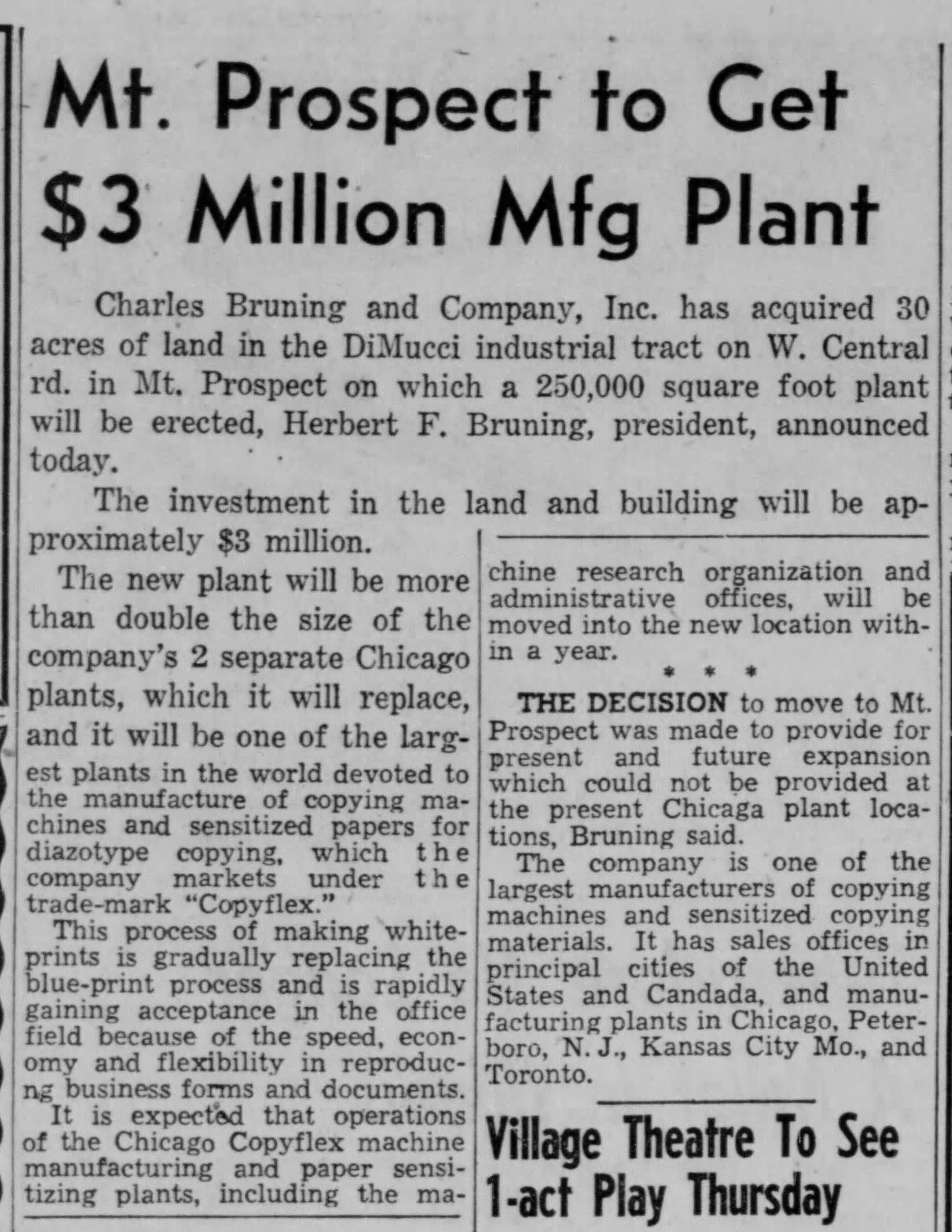

Danish immigrant Charles Bruning founded the New York Blue Print Paper Company in Manhattan in 1897. Renamed for its founder in 1927, the Charles Bruning Co.’s growth soared in the late 1920s after they brought diazotype printing to the US–the chemical process that enabled whiteprints to mostly supplant blueprints for architectural drawings. While the company made the machines and equipment for blueprints and whiteprints, most of their revenue actually came from producing the paper itself.

Three Charles Bruning Co. ads

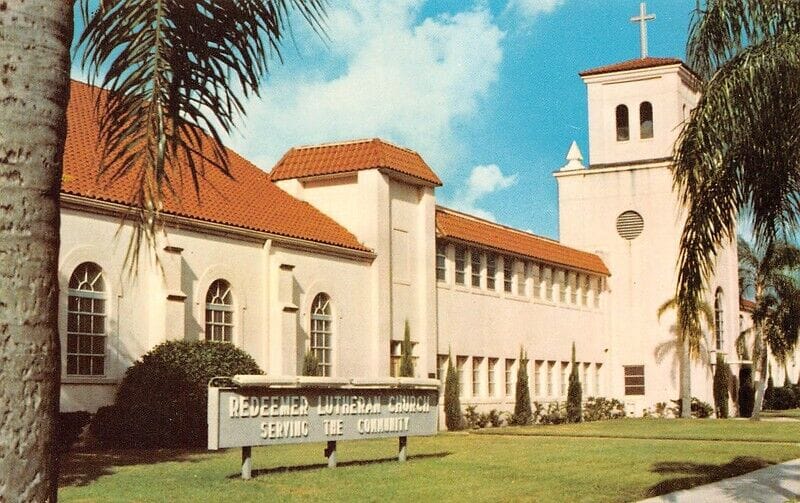

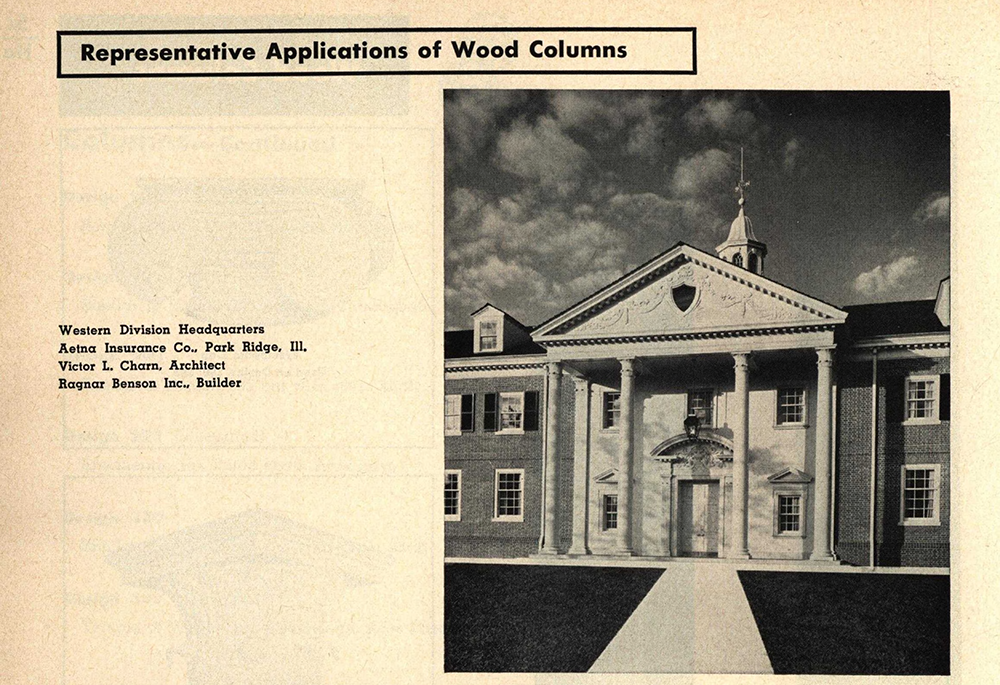

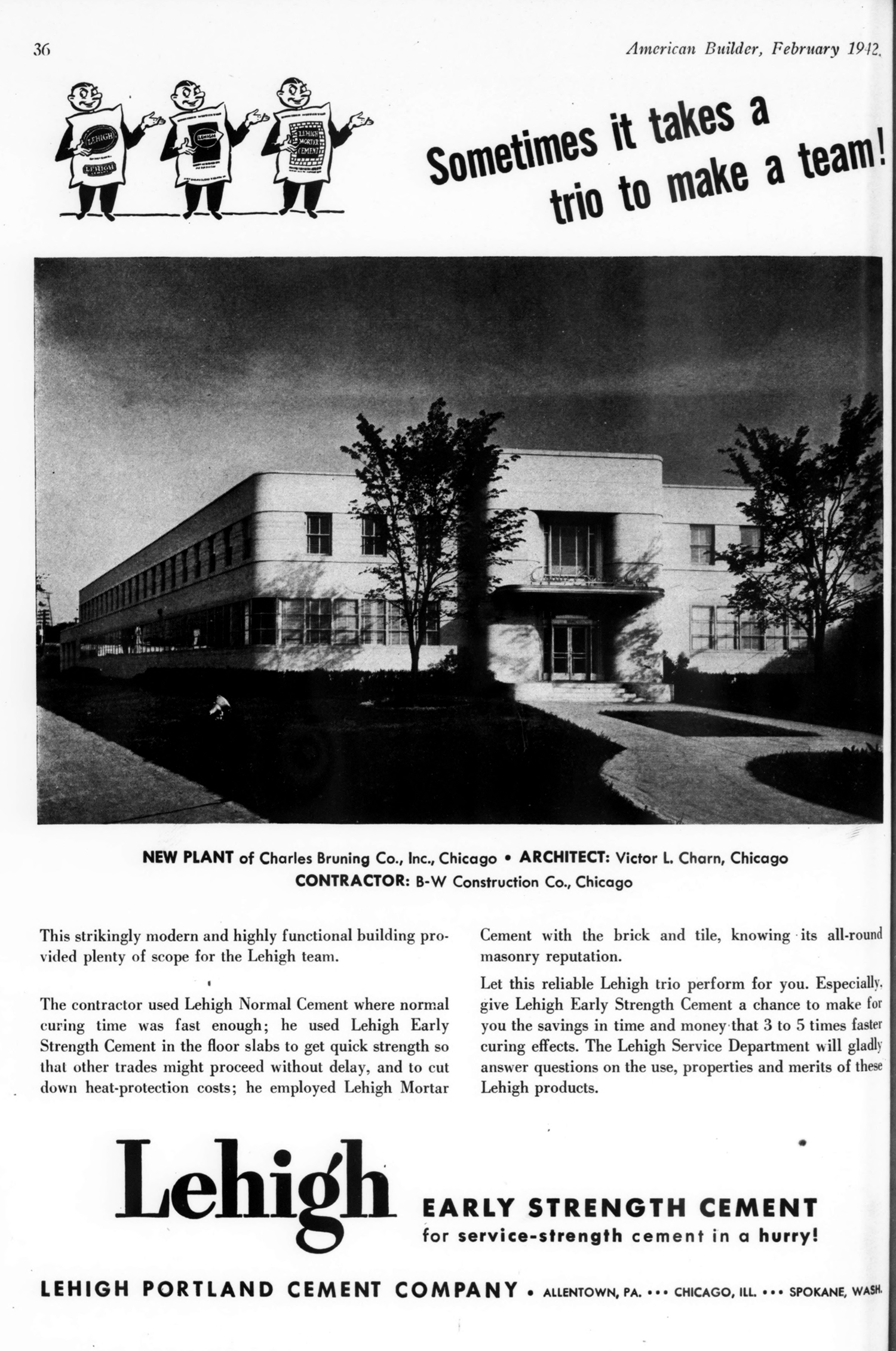

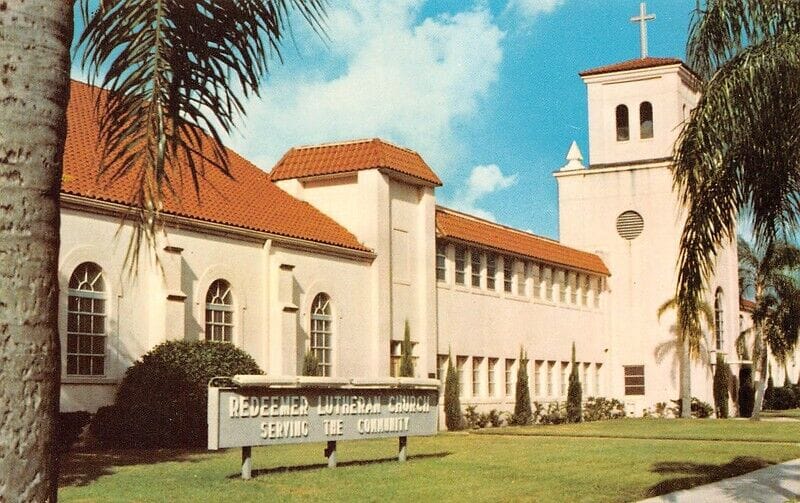

The architect here, Victor L. Charn, had a great stretch from the late 1930s to the 1950s designing slick Art Moderne industrial architecture around Chicago, including a gorgeous Motorola radio factory and a temple-like lab for Nalco. There were also some quirks and clunkers in there, including an unexpected Lutheran church in Florida and a dreadful colonial revival insurance office in Park Ridge.

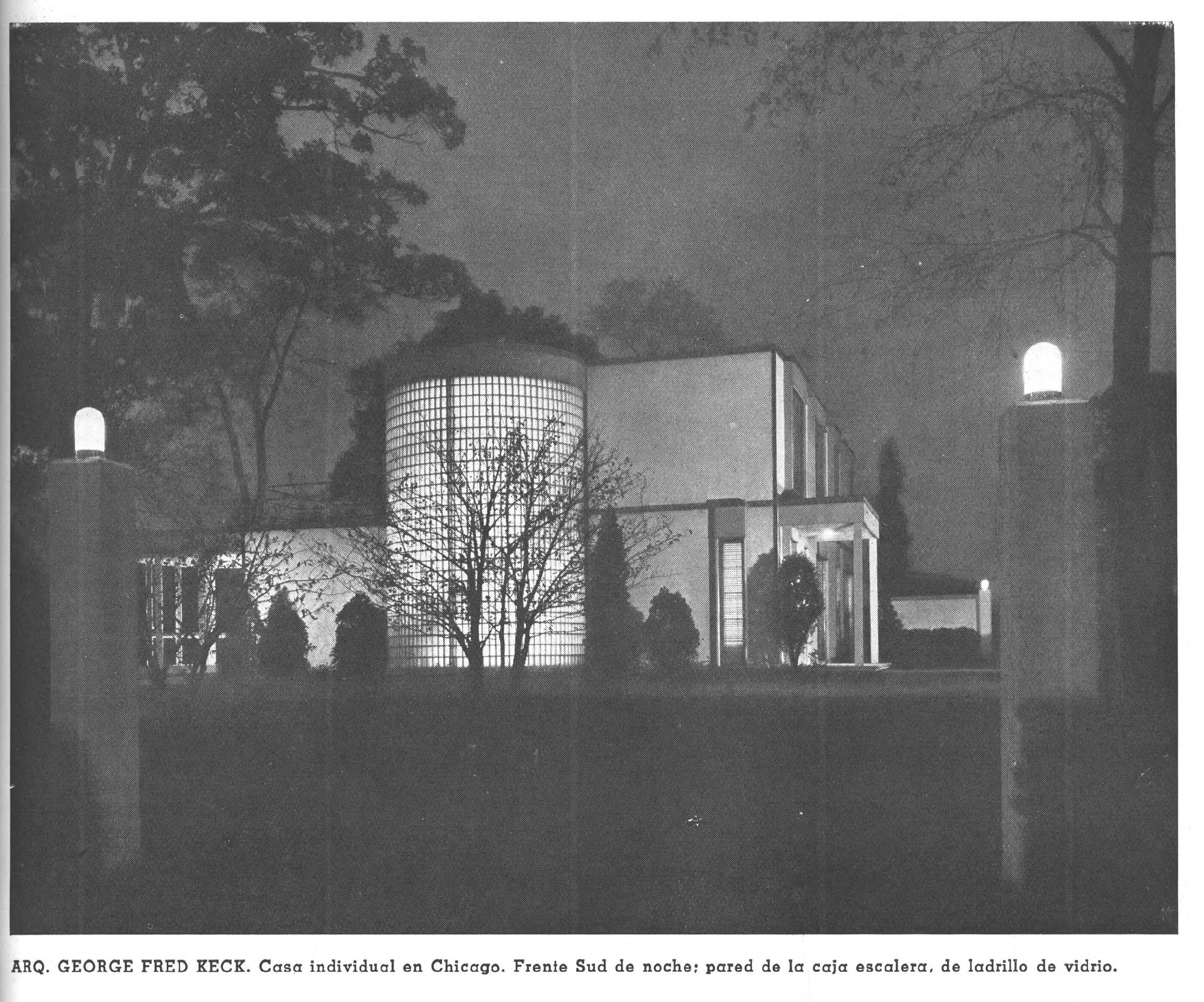

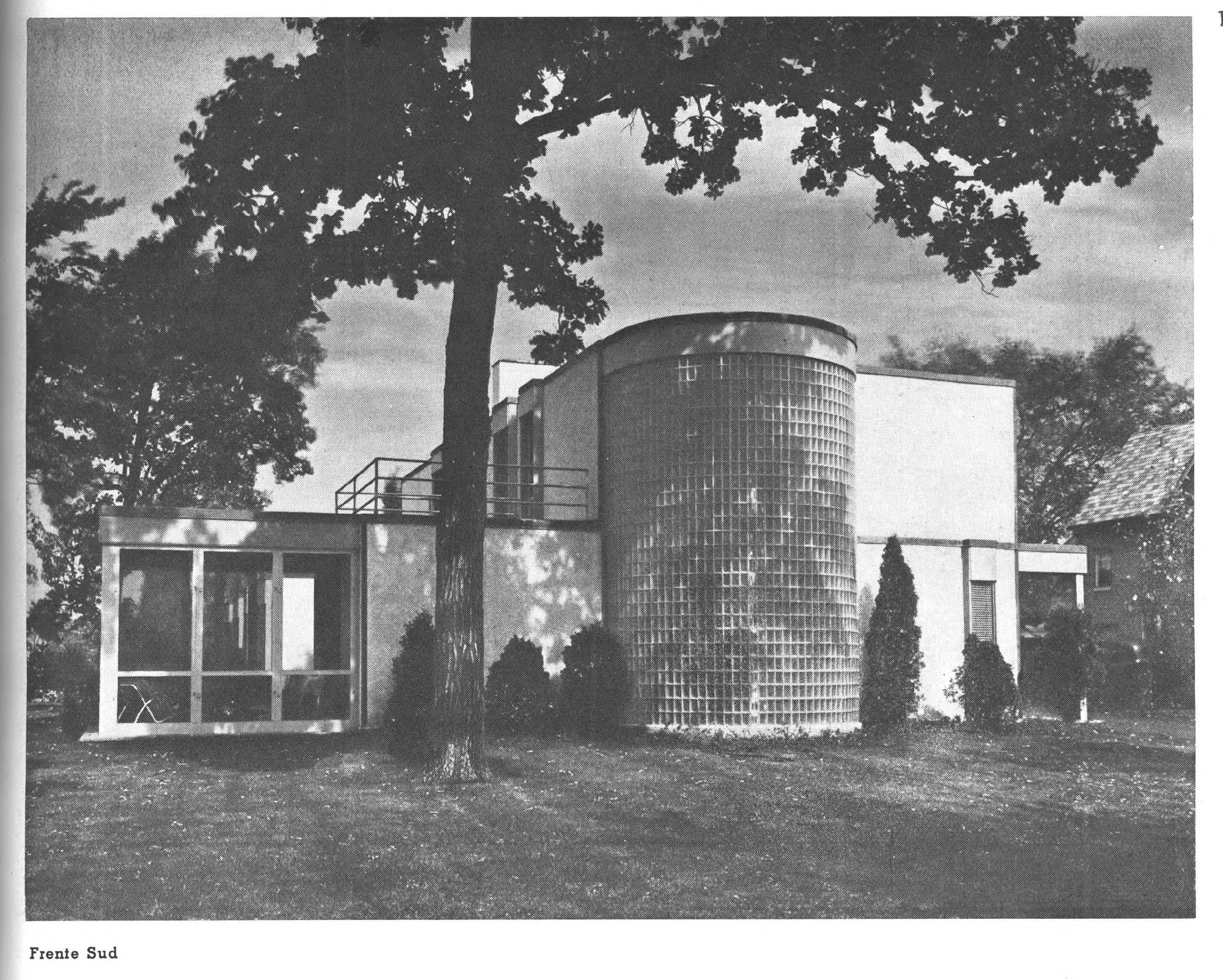

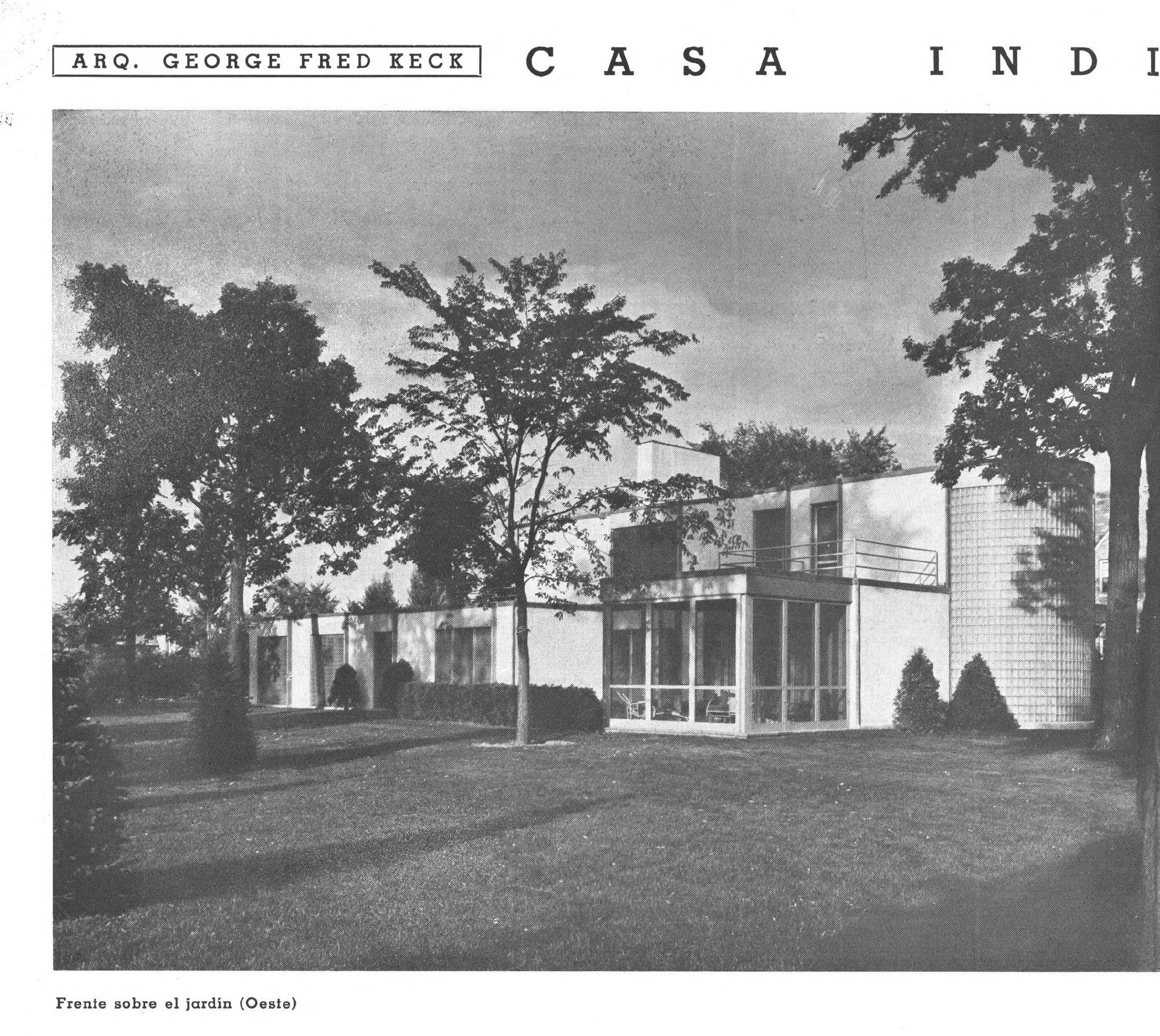

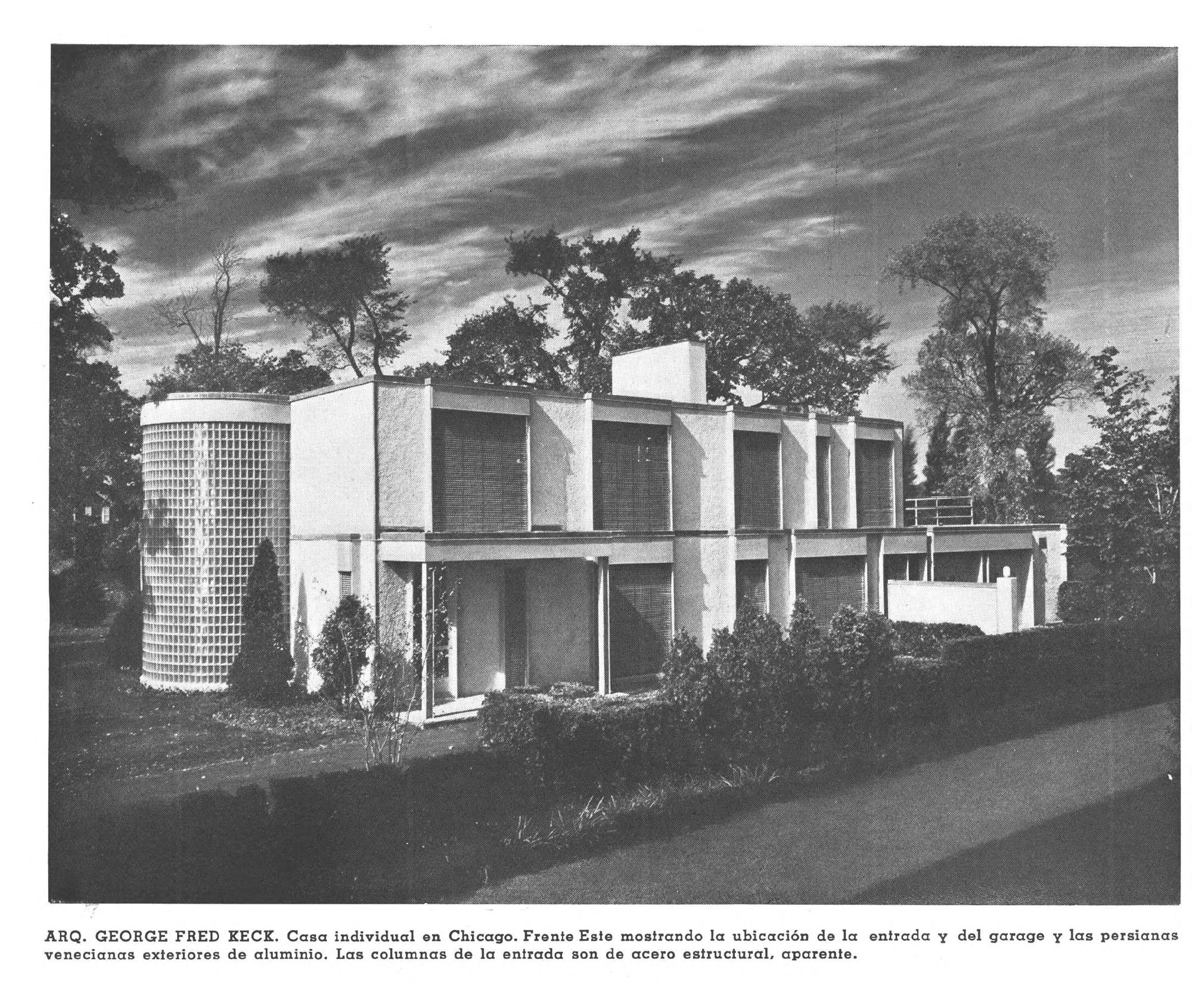

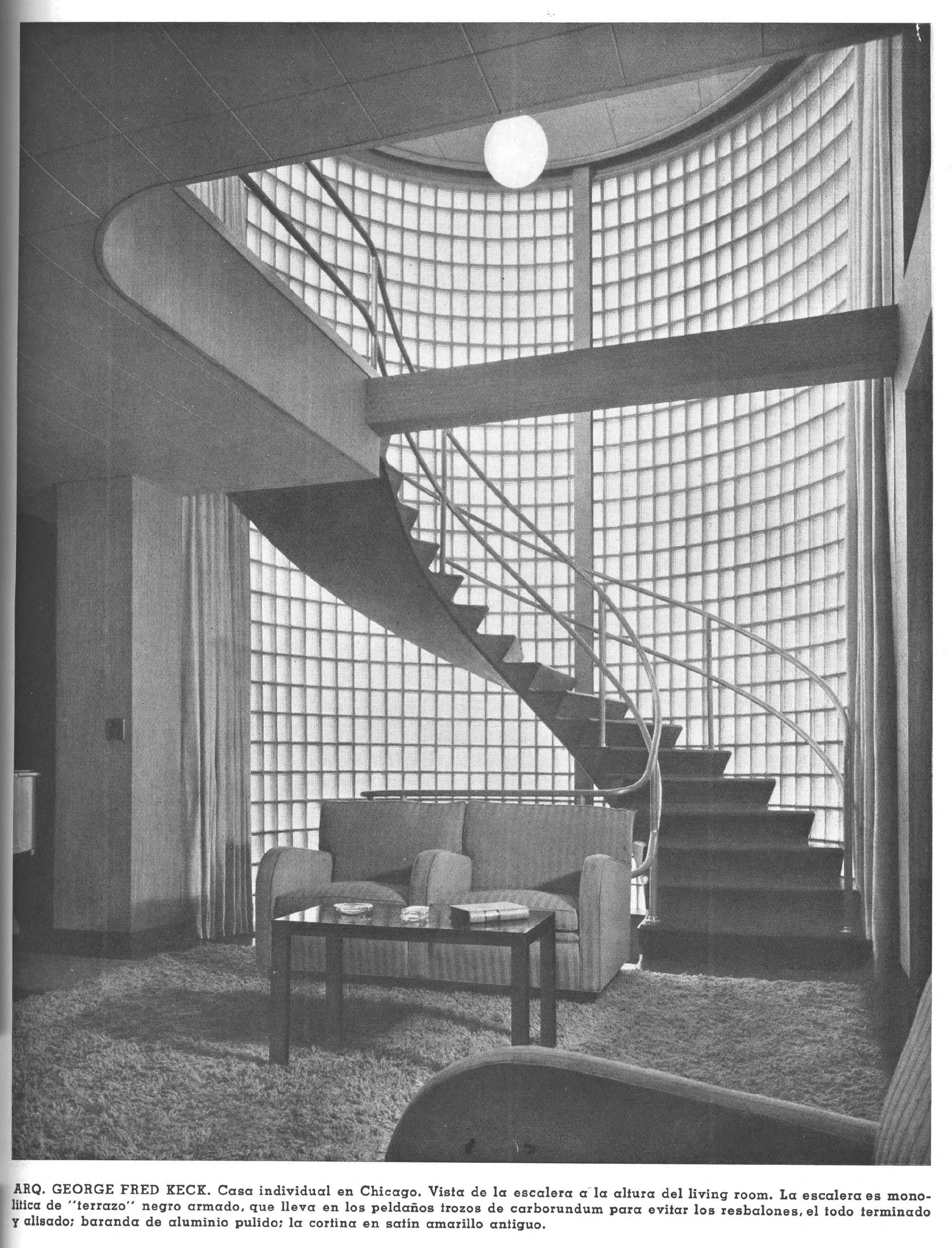

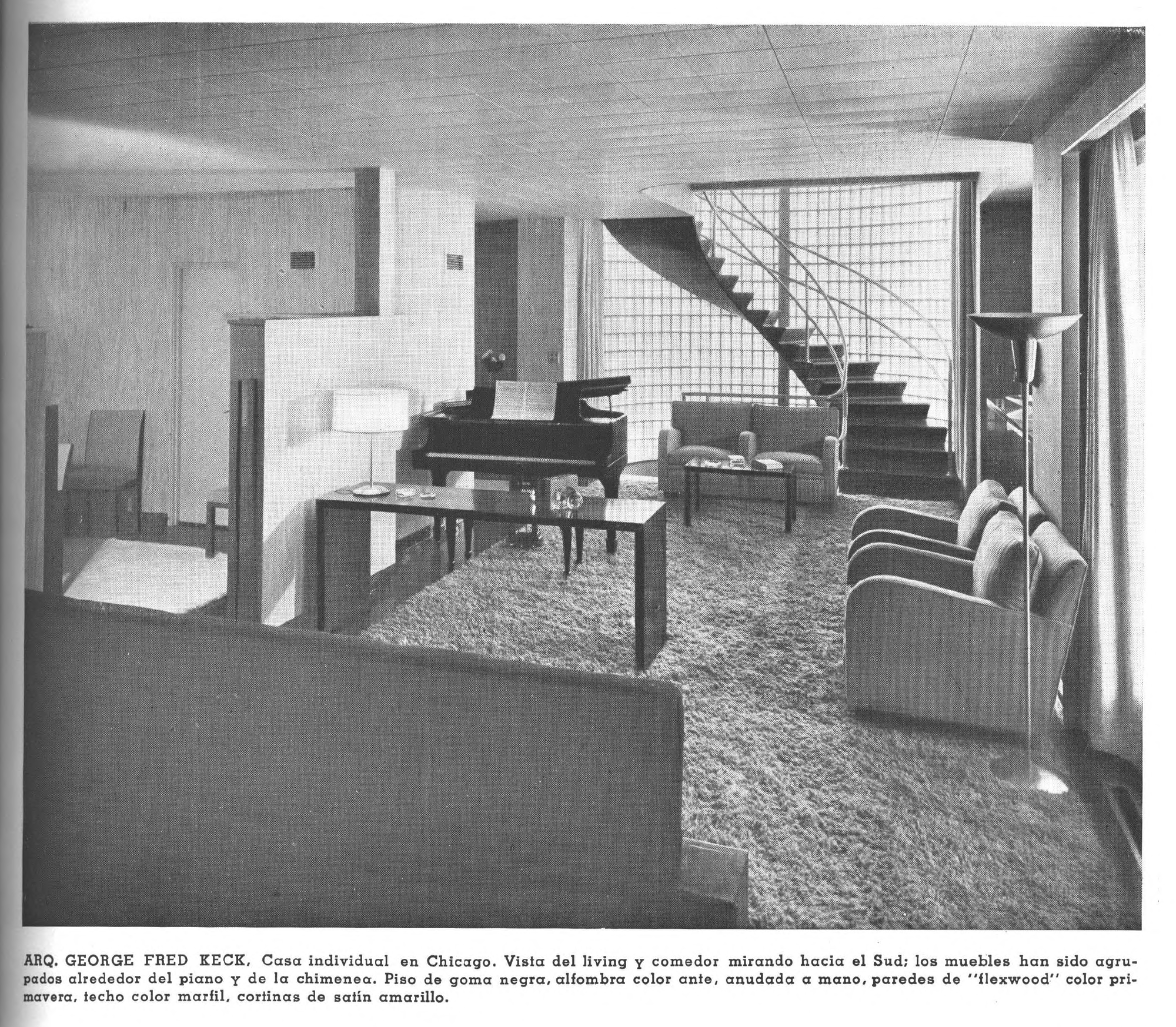

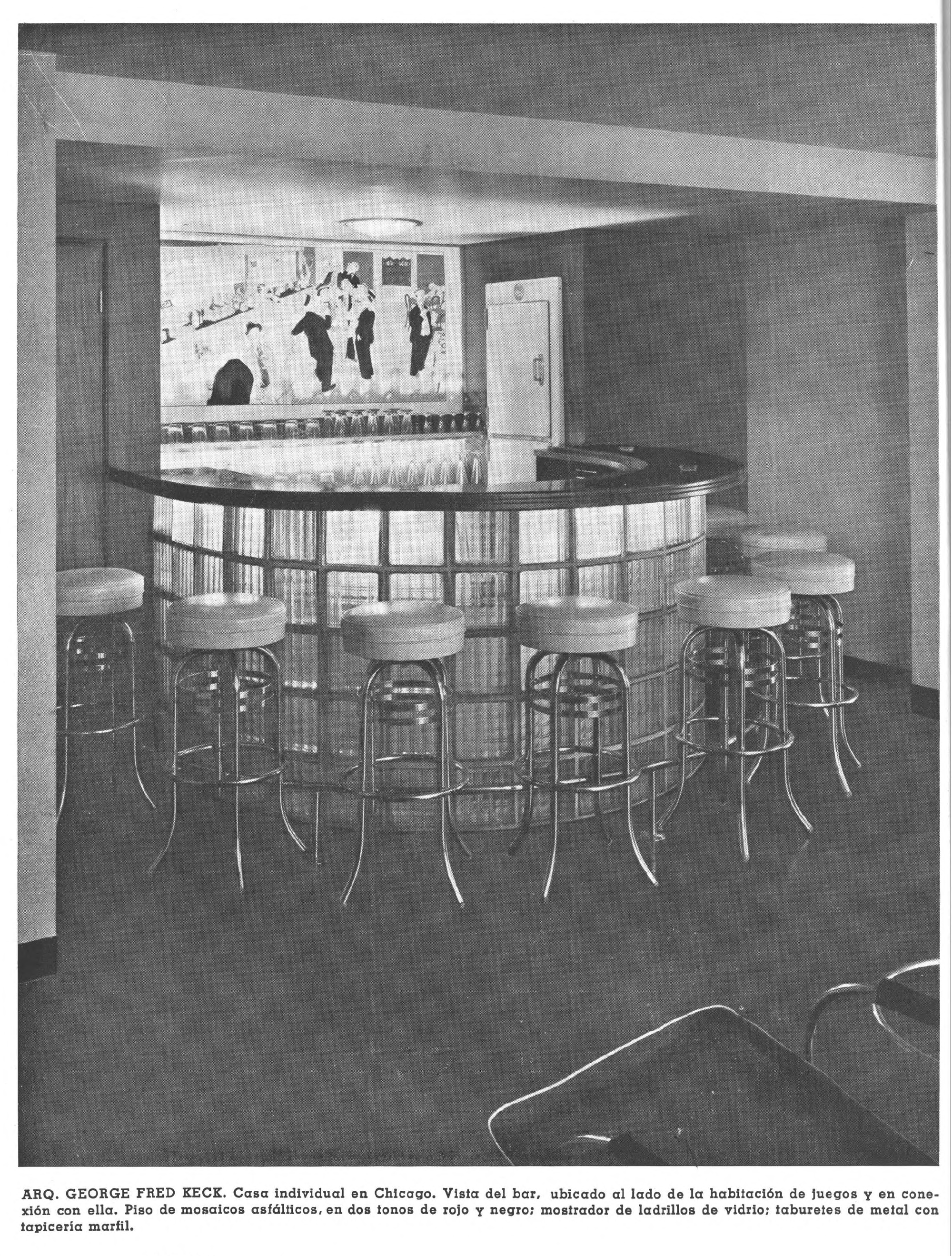

Good taste in architecture apparently ran in the Bruning family–the founder’s son and future CEO Herbert Bruning hired brilliant Chicago modernists Keck & Keck to design him a stunning home in Wilmette in 1936.

Charn-designed office and lab for National Aluminate Corp., 1936, Northwest Architectural Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries | Charn-designed Motorola radio factory in an American Terra Cotta Corp. catalog, 1940, Building Technology Heritage Library, the Internet Archive | 1938, Charn-designed Tropic-Aire factory at Kilbourn & Augusta | 1948 article on a Charn-designed warehouse for Wrigley | postcard of the Charn-designed church in St. Petersburg, Florida | the Charn-designed Aetna Insurance office in Park Ridge, 1960, in a Hartmann-Sanders catalogue, Building Technology Heritage Library, the Internet Archive | Photos of Keck and Keck's Bruning House in Wilmette, 1938, in Nuestra Arquitectura, the Internet Archive

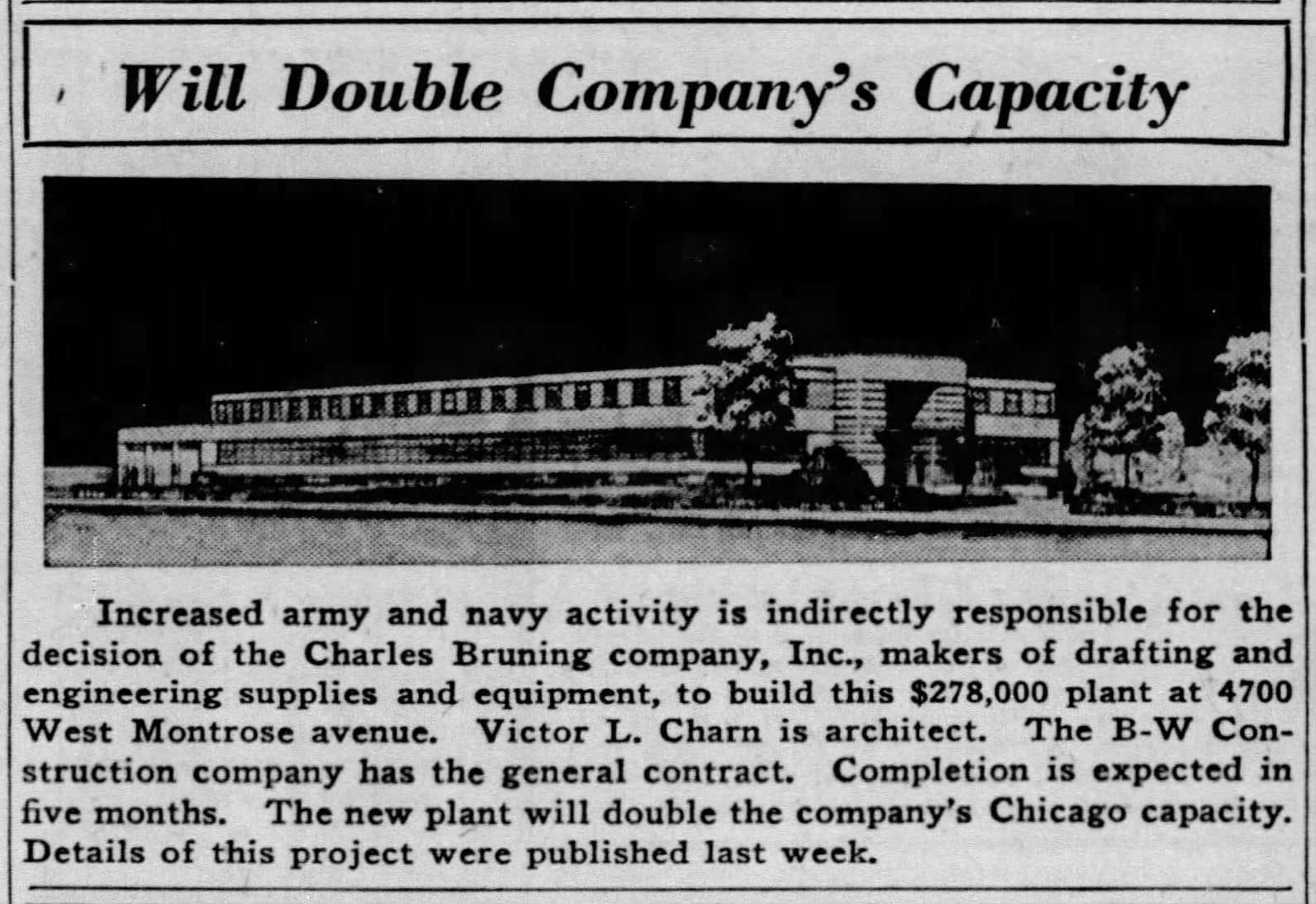

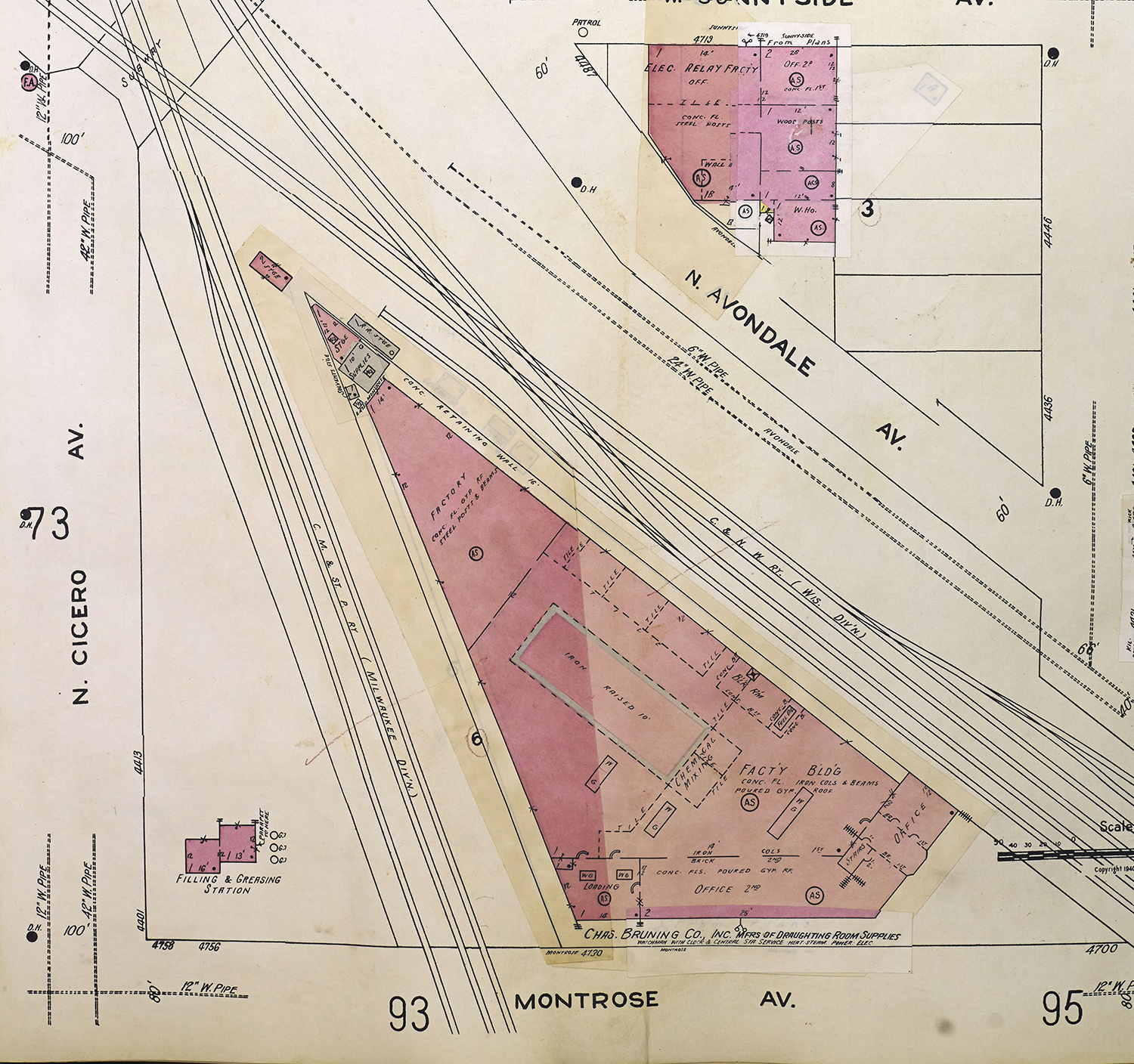

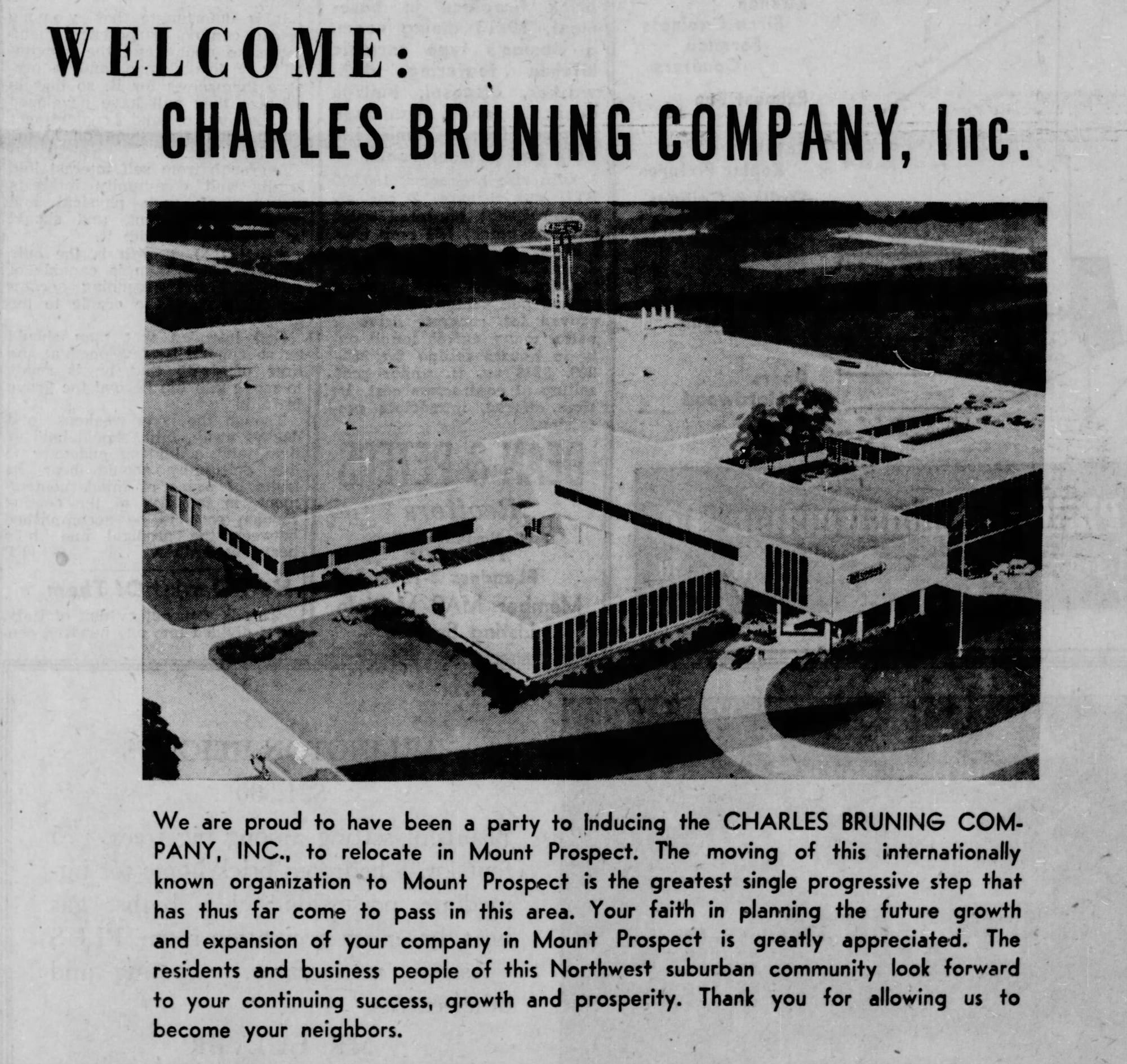

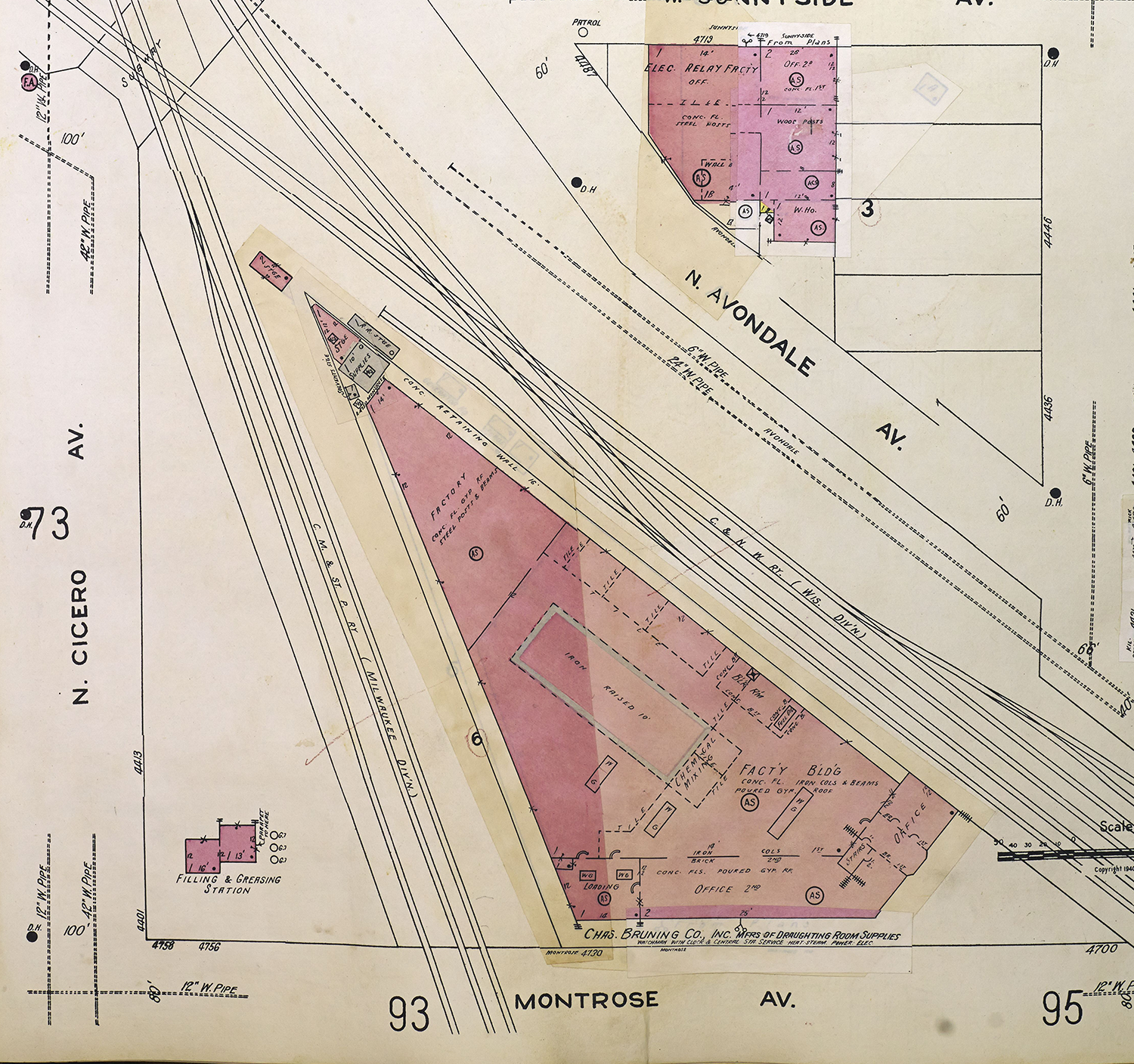

Less than a year after starting construction here in 1940–building a facility that initially doubled their production capacity–Charles Bruning Co. pulled a permit to expand the factory even more. Hemmed in by two different railroad lines, there was a hard cap on further expansion. I imagine they quickly realized that this oddly-shaped site wasn't going to be a long-term home for a growing company–and that was before the company relocated their headquarters to Chicago. Seeking more space, in 1957 the company opened a large office and manufacturing complex in the suburbs.

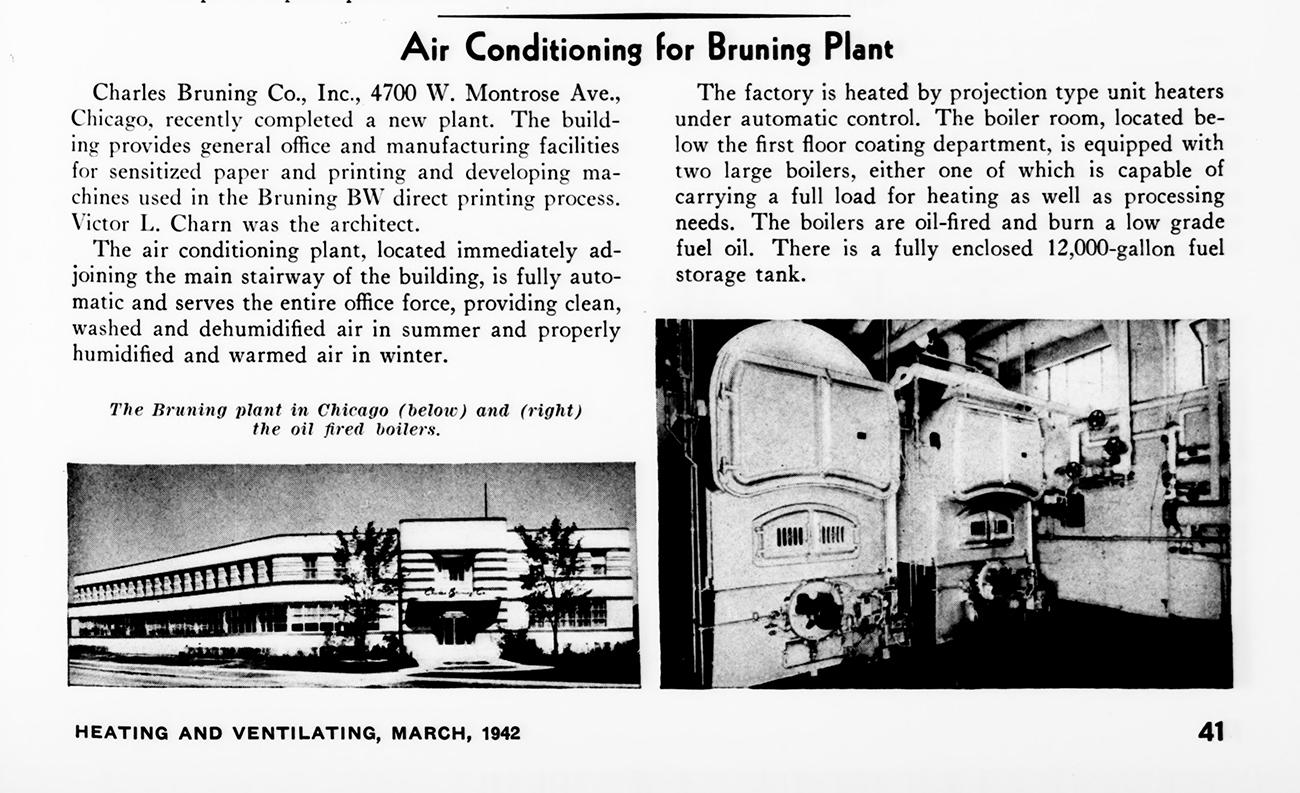

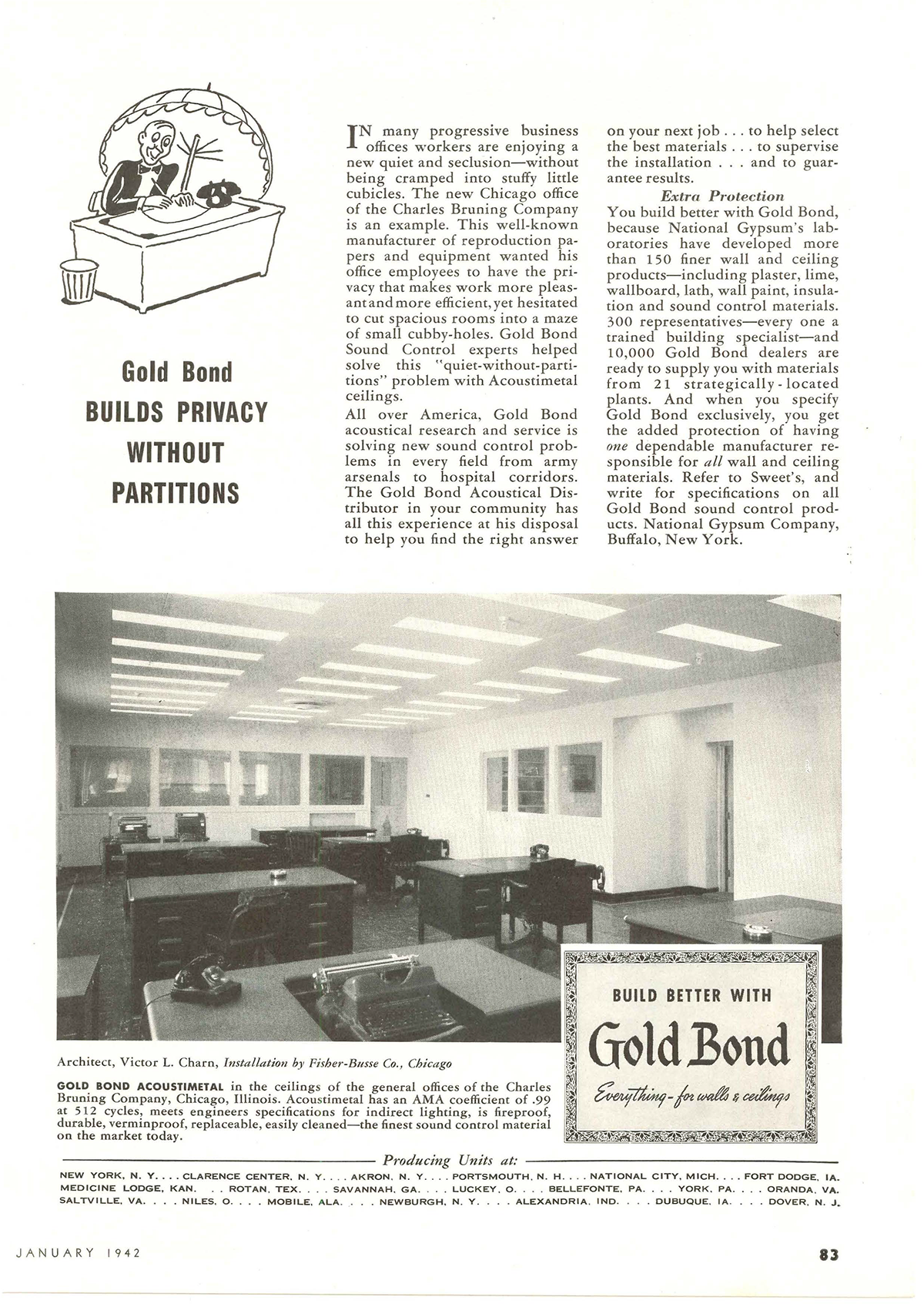

"Chicago Plant of Bruning Co. to be Doubled" and "Will Double Company's Capacity, October 1940, the Chicago Tribune | in Air Conditioning, Heating and Ventilating, 1942, the Internet Archive | in a cement ad, American Builder, 1942, the Internet Archive | Office view in a Gold Bond Acoustimetal ad, Architectural Record, 1942, USModernist |1950 Sanborn Map | 1956 articles on the new Charles Bruning Co. complex in Mt. Prospect

Charles Bruning Co. merged with the Addressograph-Multigraph Corporation in 1963, and within a year the combined entity was leveraging Bruning IP to attack Xerox patents. The company made up the Multigraphics business unit of AM International, but within 20 years AM had filed for its first Chapter 11 bankruptcy. They filed for Chapter 11 again in 1993, ultimately reorganizing the company under the Multigraphics name, before selling itself off in 1999.

Back on Montrose Avenue, International Register Co. moved into the Charles Bruning building in 1962. Renamed Intermatic, the company manufactured control timers for lamps from this building until they moved out in the 1980s. Since then, the building housed an elevator company, some kind of lab, a few sketchy looking telemarketers, a maker of soldering equipment, and a security camera company.

Maybe a little rough for wear and underutilized today, it remains a fantastic example of the verve and optimism of early industrial modernism. I hope this one sticks around for another 80+ years.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Good Forgotten Chicago post on Charles Bruning Co.

- WBEZ looks at two Victor L. Charn-designed factories in Humboldt Park

1938 aerial of the site, Illinois State Geological Survey | 1950 Sanborn Map

Over the course of his career architect Victor L. Charn had a firm of his own as well as working in-house for major Chicago construction firm Ragnar Benson. One of Chicagoland's best designers of modernist churches, Charles Stade, briefly worked for Charn's firm in the late 1940s or early 1950s–a delightful crossover of industrial and ecclesiastical modernists. I'm a big fan of Charn's work, but old factories in disinvested communities , unfortunately many of them have been demolished in recent years.

National Aluminate Corporation (Nalco) office and lab in 1936. At some point it was refaced with brick and it was demolished in the 1990s. University of Minnesota Libraries, Northwest Architectural Archives | Charn-designed floral shop with apartments above in 1940, location unknown, the American Builder, the Internet Archive | Motorola factory at Augusta & Kilbourn in Chicago in 1936, Northwest Architectural Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries | Motorola factory on Augusta & Kilbourn today, Streetview | Aetna Insurance Western Division Office, Park Ridge, IL, Streetview | Tropic-Aire plant at Augusta & Kilbourn, Streetview | Wrigley warehouse, at 1537 W. 35th Street in Chicago, demolished, Streetview | Cushing Blue Print Paper Co. at Karlov & Parker in Chicago, demolished, Streetview

In 1950, Charn got an unusual commission for a Chicago-based architect who mostly designed factories: a Lutheran church in Florida. It's still there, most recently used an office for a travel insurance company. If you want to see interior photos and read more about the church:

1950, Lutherans start to construct Charn's church | in a 1954 ad in Church Management, the Internet Archive | 1960s postcard | 2023 streetview

Charles Bruning Co. heir Herbert Bruning and his wife Vine Itschner hired Keck & Keck to design them a GORGEOUS mansion in Wilmette.

Photos of Keck and Keck's Bruning House, 1938, in Nuestra Arquitectura, the Internet Archive

Member discussion: