A staggering number of theaters once packed American cities, and Broadway was the flashy heart of Portland’s entertainment district. Headlined by the Paramount and the Broadway theaters—amongst the seven marquees visible in this 1930s postcard—today Broadway hosts…two.

After nearly a century of intertwined and diverging trajectories of vaudeville, cinema, rock, landmarking, Blazers, vandalism, demolition, rebirth, and redevelopment, the former Paramount Theater on the left is now the Portland Center for the Performing Arts’ Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, and the 24-story office building that replaced the Broadway Theater now hosts the Judy, the Northwest Children’s Theater.

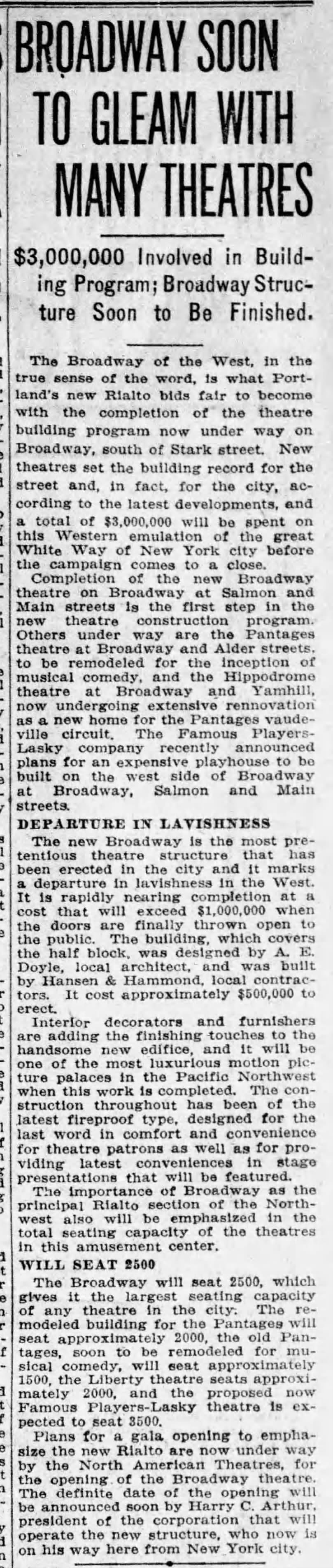

Before that, though, they were competitors that helped define Portland’s “Great White Way”. The Broadway Theatre arrived first, opening in 1926 and designed by A.E. Doyle, before the Paramount Theatre, designed by Rapp & Rapp, opened in 1928 as the Portland Publix.

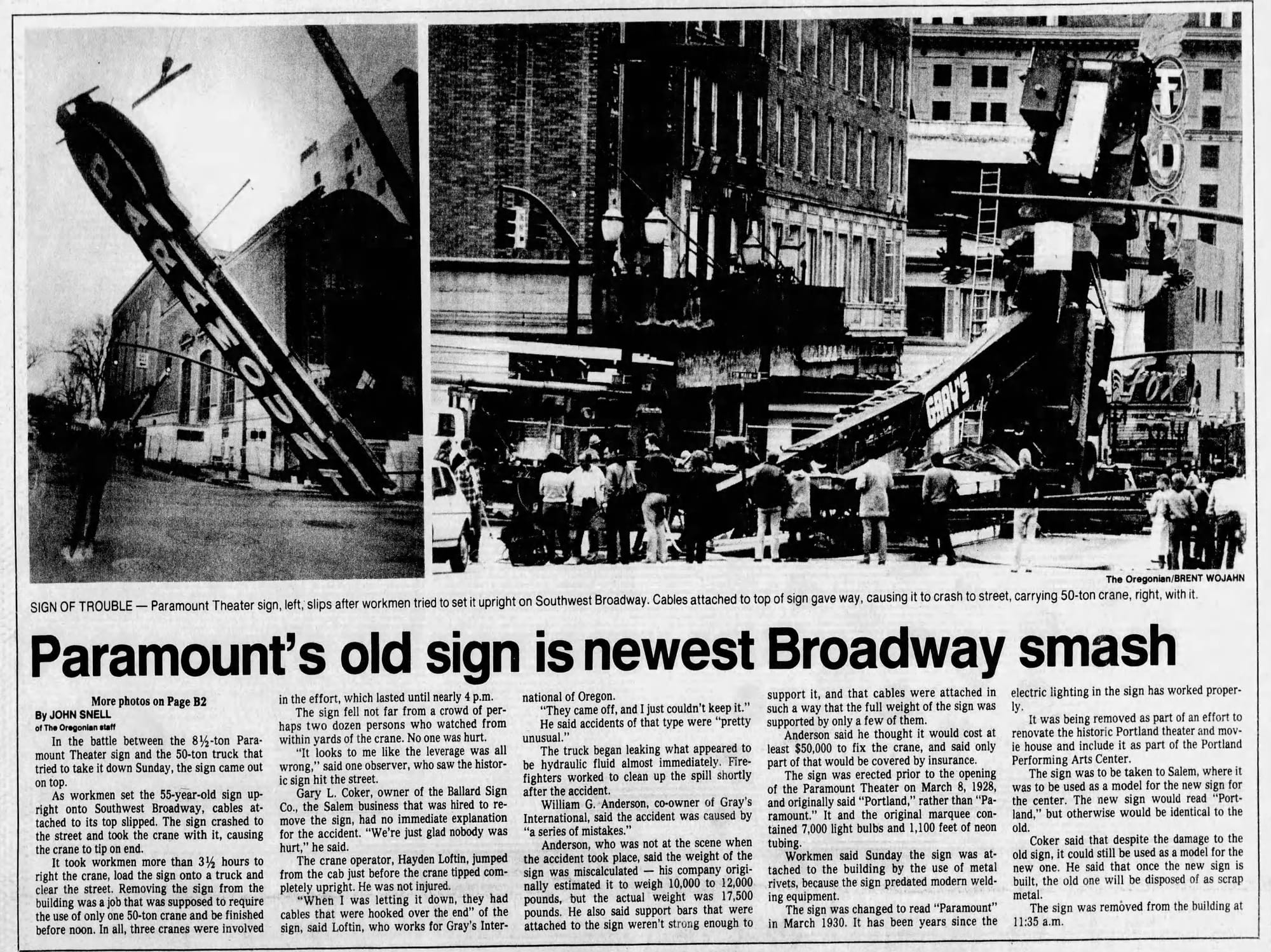

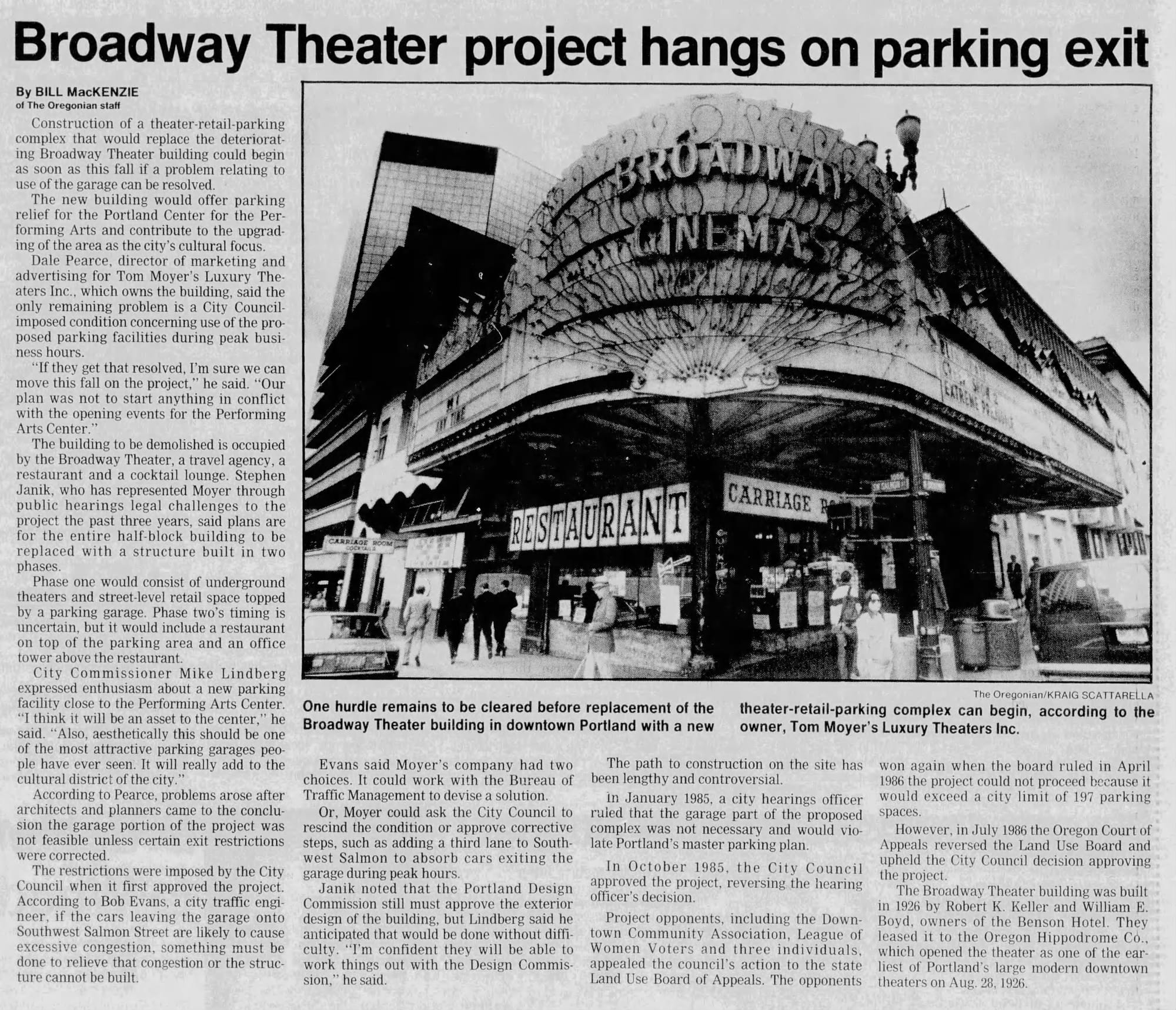

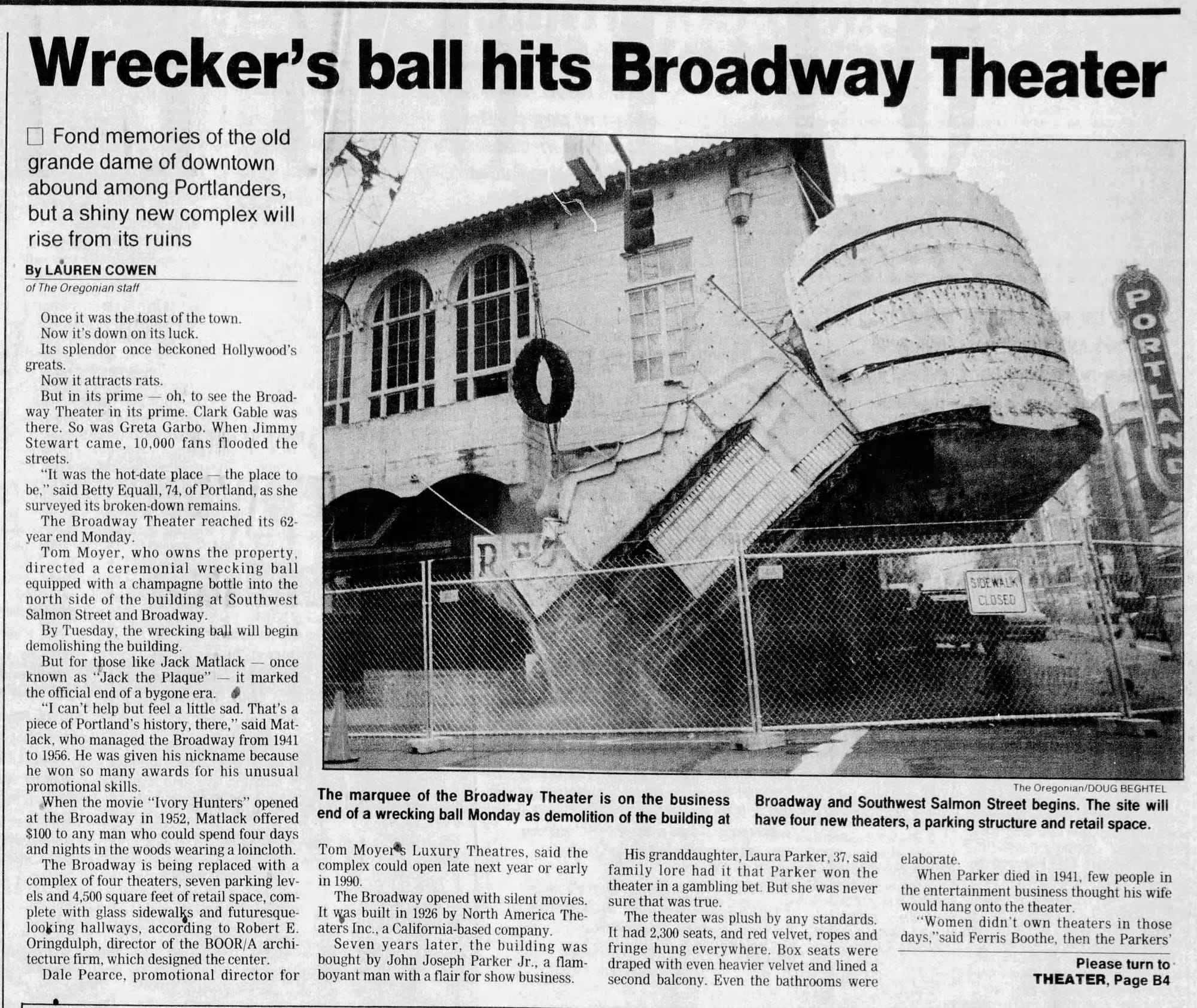

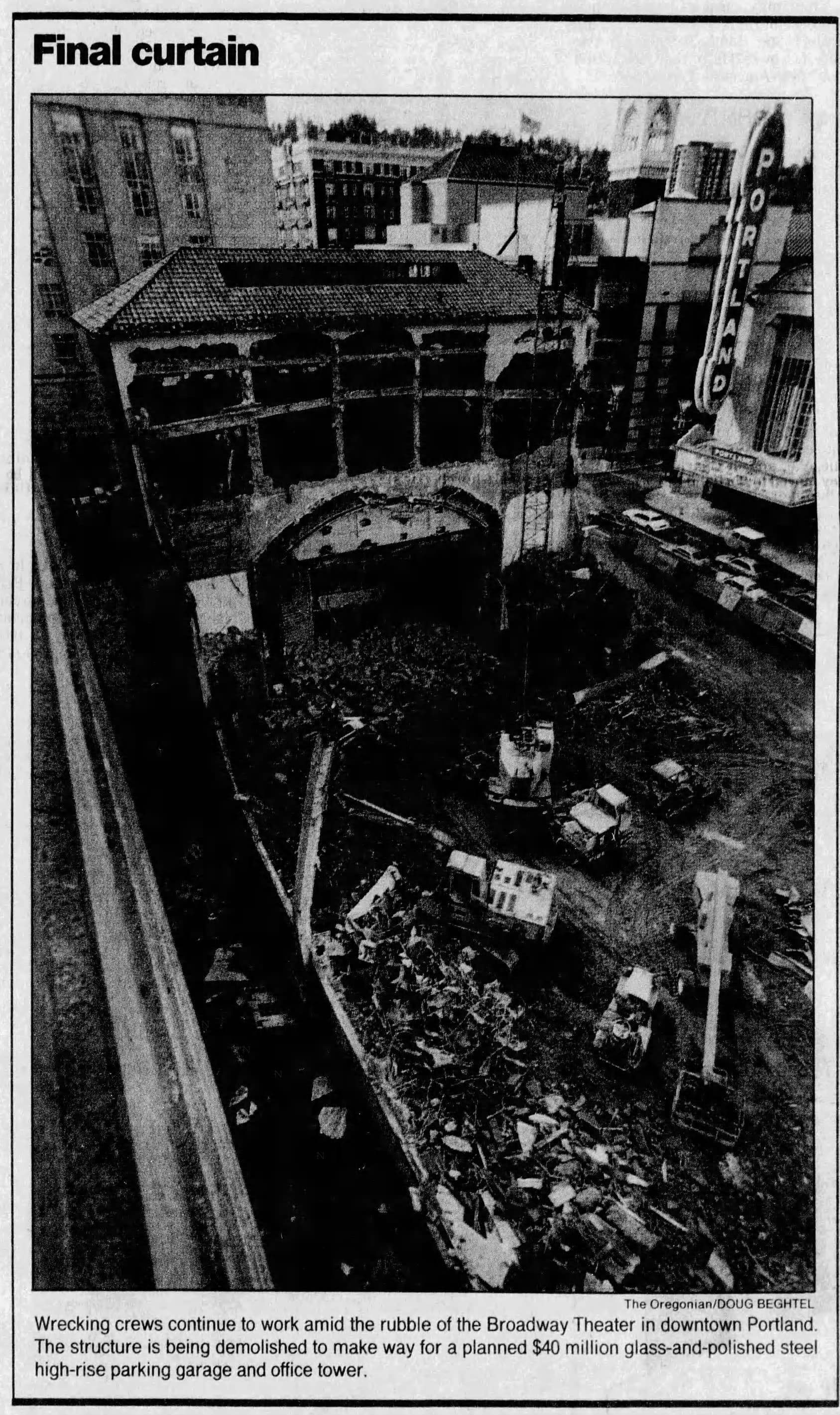

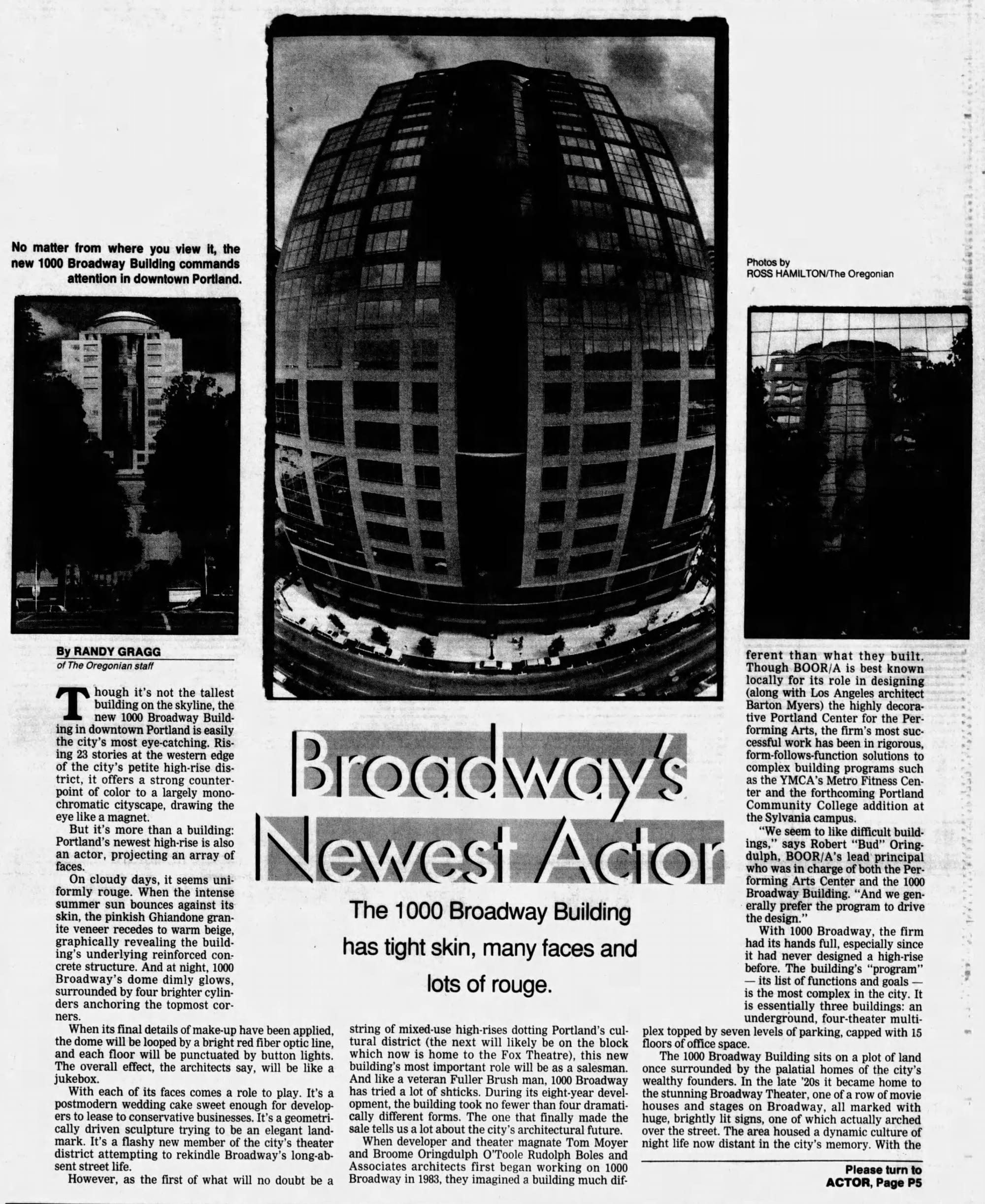

So, what’s changed? So many more street trees and a bike lane. On the left, in connection with its reopening as the Arlene Schnitzer Concert, a new “Portland” marquee evoking the Paramount was installed in 1984. Next door, the Heathman Hotel received new windows but otherwise looks the same. Formerly a two-way street, Broadway is now one-way heading southwest—the conversion of major thoroughfares to dangerously fast one-ways feels under-examined to me. The Mediterranean Revival style Broadway Theater was demolished in 1988 as Tom Moyer redeveloped it into 1000 Broadway, reminiscent of a stick of roll-on deodorant. It’s obscured by the trees, but the office building does have a recreation of a Broadway sign—not the original, but an odd vestigial placemaking nod to it.

1927 article on the groundbreaking, Exhibitors Herald, the Internet Archive | 1927 article on the groundbreaking, Oregon Daily Journal | 1928 sketch in the Von Duprin Fire Exit catalog, the Internet Archive | 1928 opening ad | in Exhibitors Herald, 1928, the Internet Archive | 1935, City of Portland Archives | New Heathman Hotel to open its doors, 1927 | Heathman Hotel opening ad, 1927 | 1948, City of Portland Archives

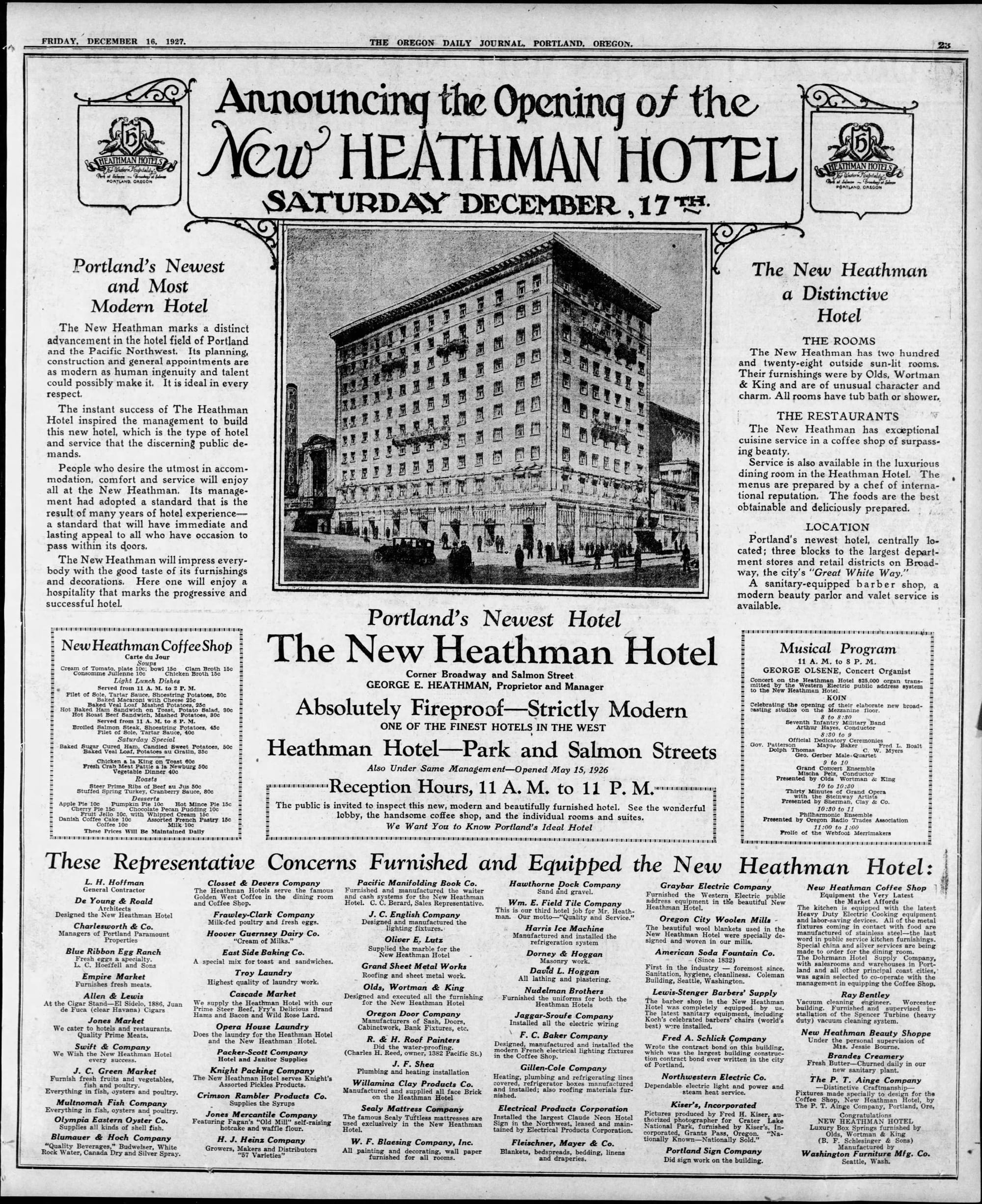

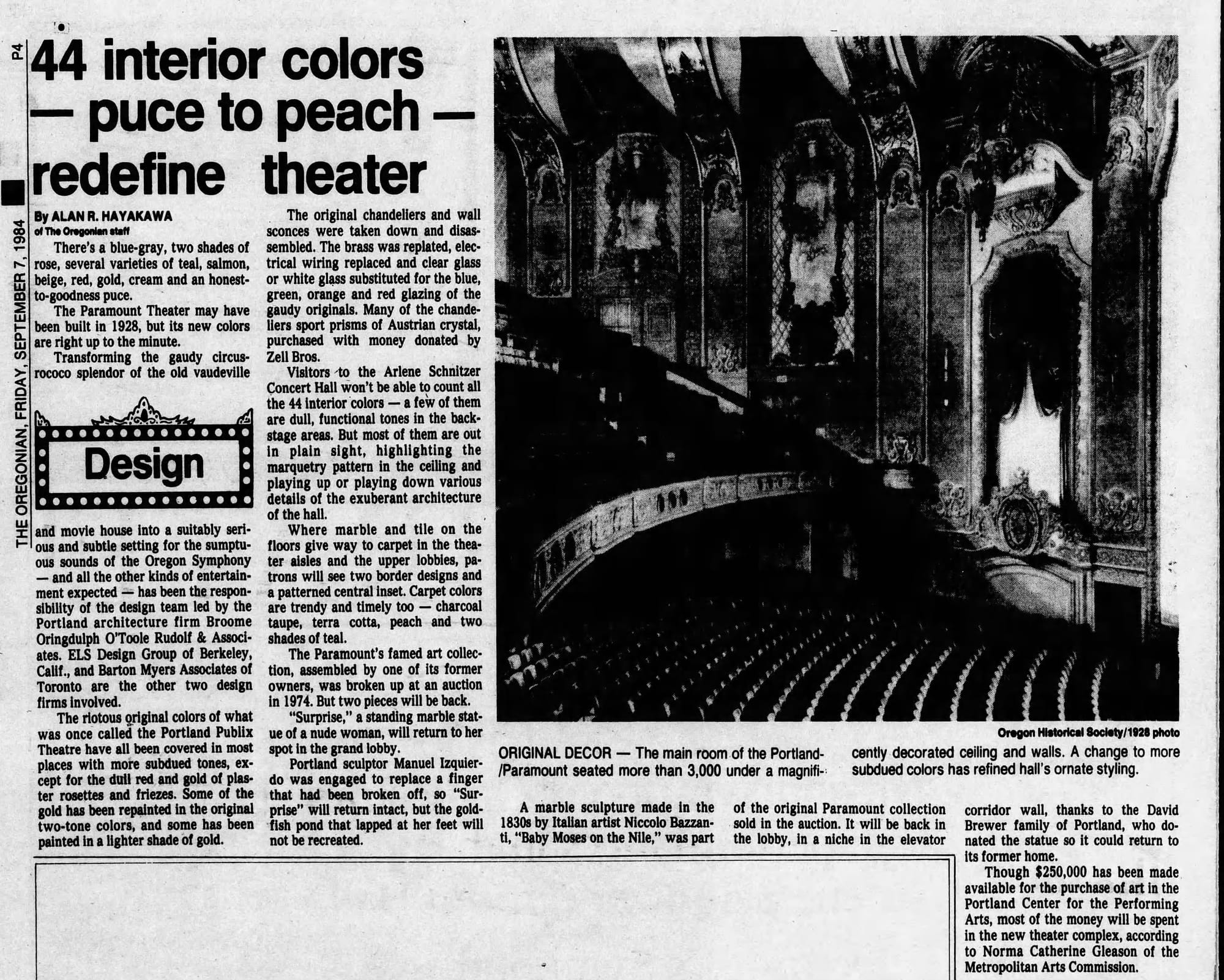

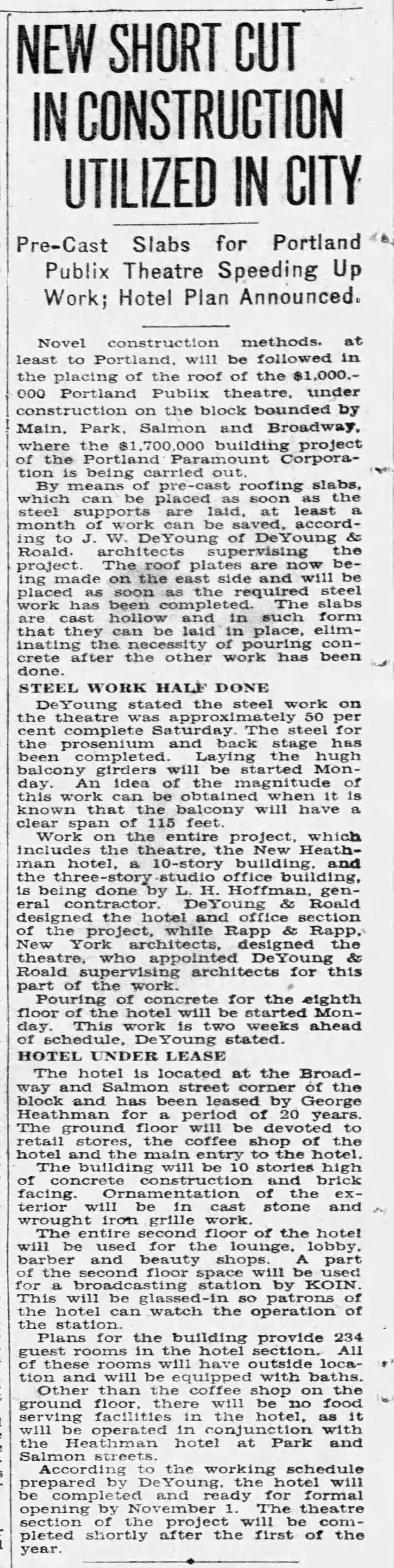

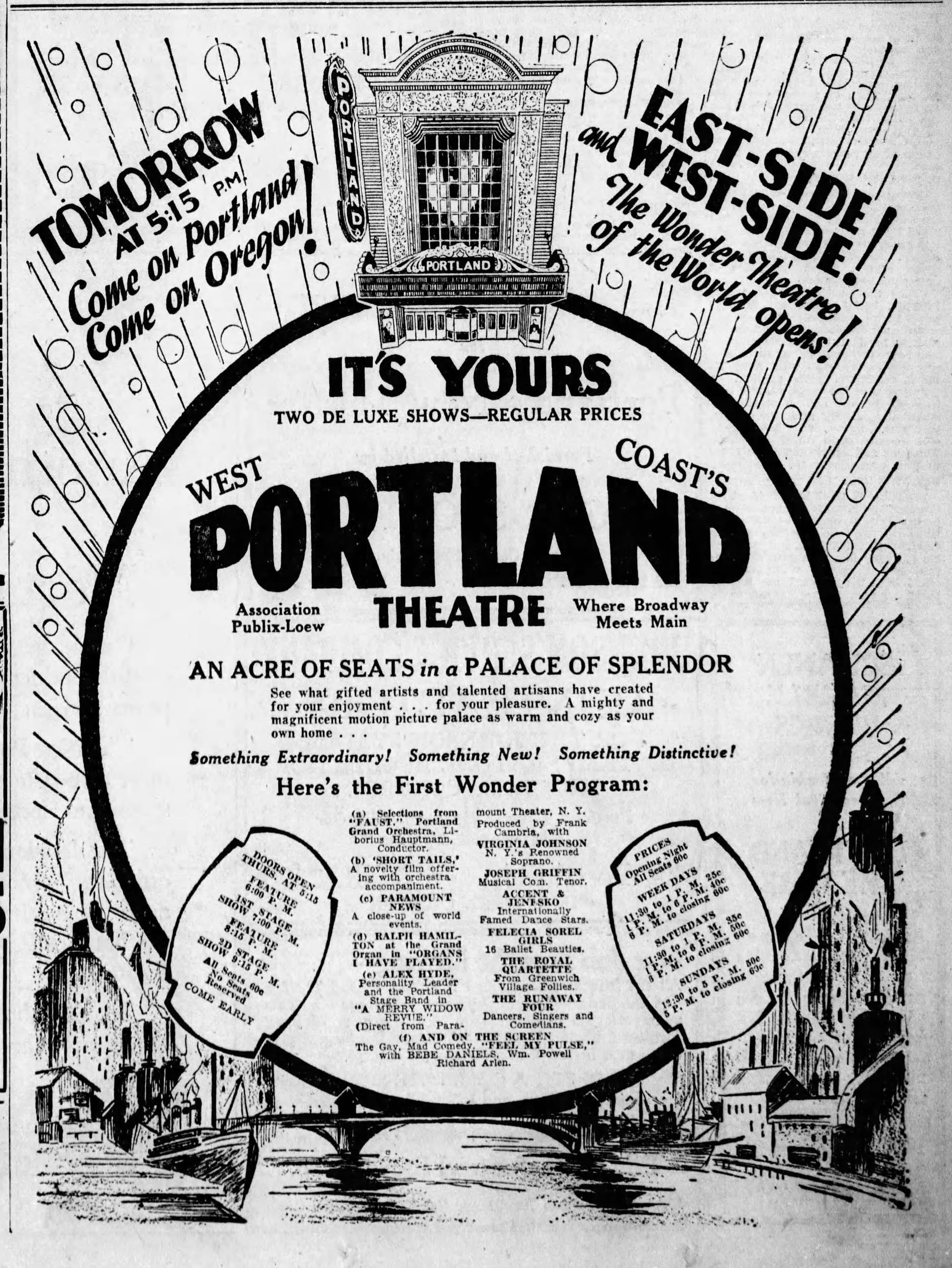

Developed in tandem with the Heathman Hotel next door, the Paramount opened in 1928 as the Publix Theatre, a massive vaudeville theater designed in the North Italian Rococo Revival style by iconic Chicago theater architects Rapp & Rapp. For Rapp & Rapp, who designed the Chicago Theater, the Uptown, and the Riviera in Chicago, this was roughly contemporaneous with their work on the Paramount Building in New York. Within a couple years the Publix was renamed the Paramount, transitioning mostly to film, and for decades it was one of the most prestigious cinemas in the Pacific Northwest.

The Paramount was inseparable from the Heathman Hotel next door—they shared investors, contractors, and Heathman Hotel architects De Young & Roald served as the supervising architects on the Paramount. In constructing the Heathman and the Paramount together in 1927 and 1928, the investors aimed to create a self-contained destination theater district—not entirely dissimilar from the way the Paramount would anchor a refreshed, publicly-funded entertainment district in the 1980s.

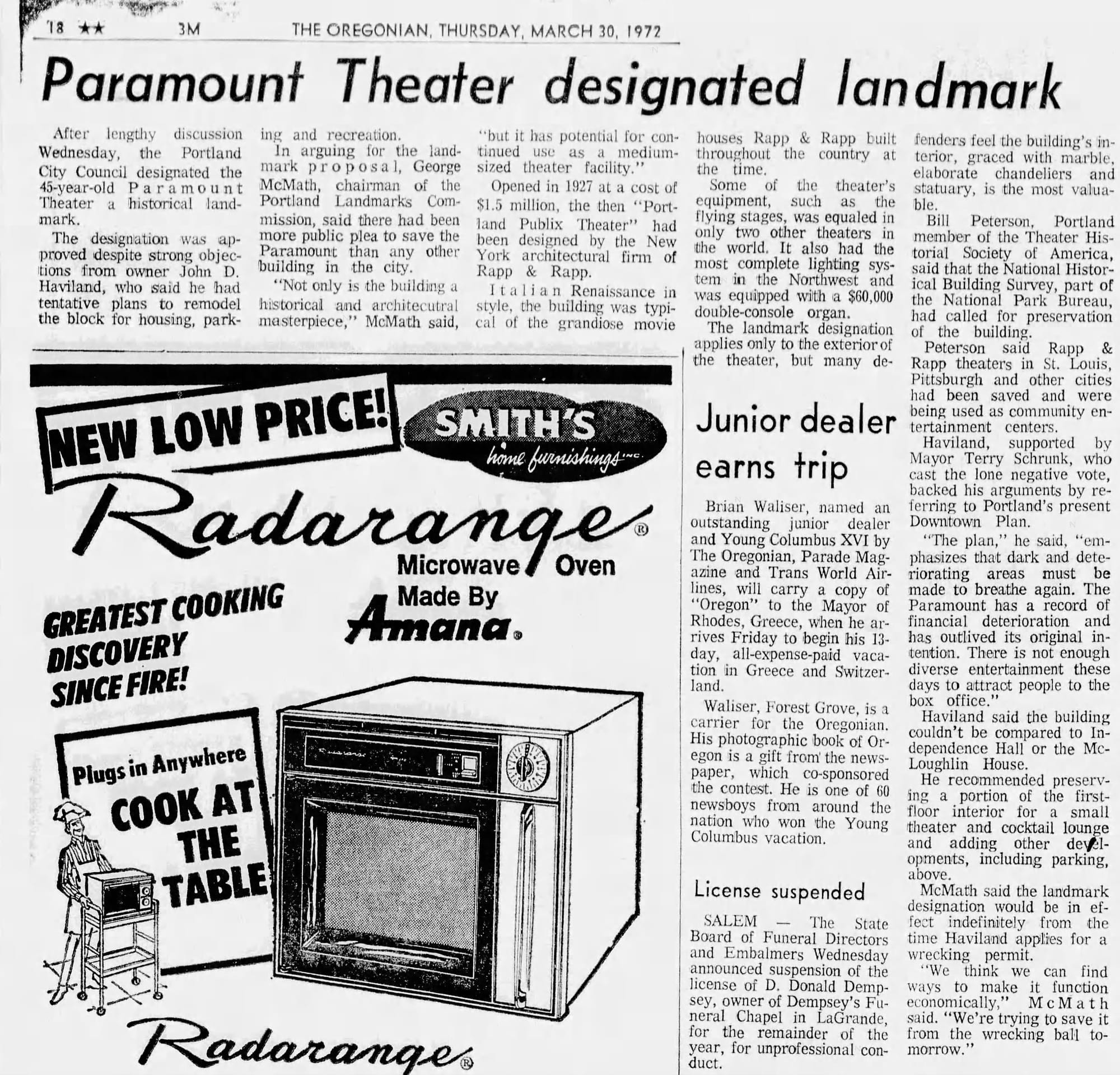

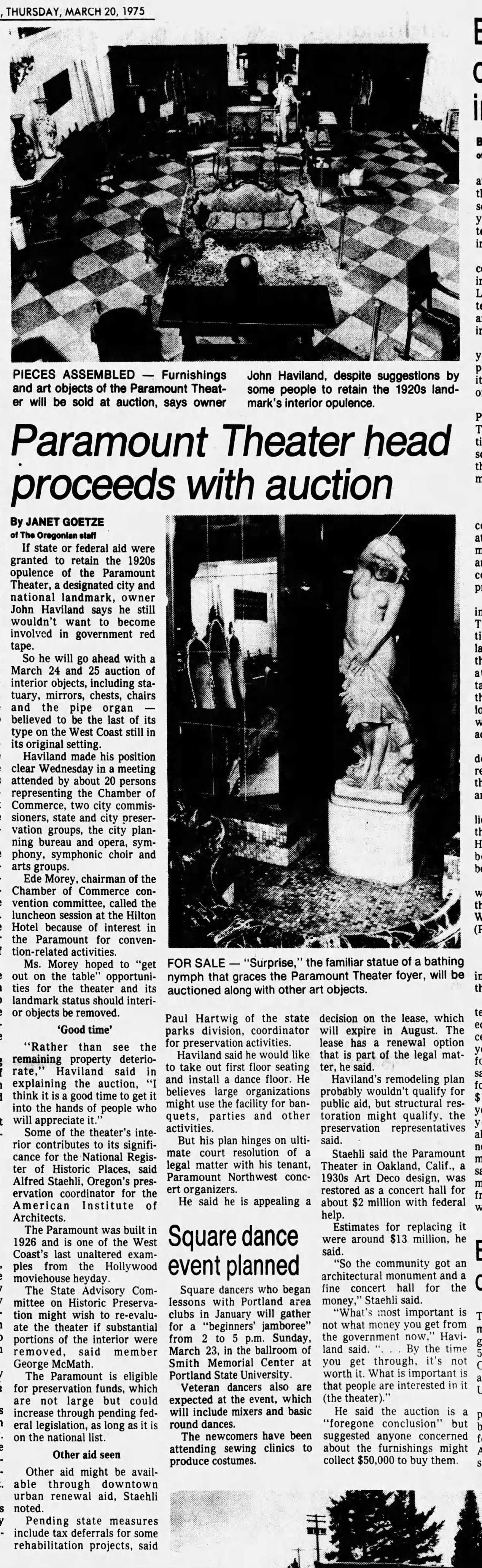

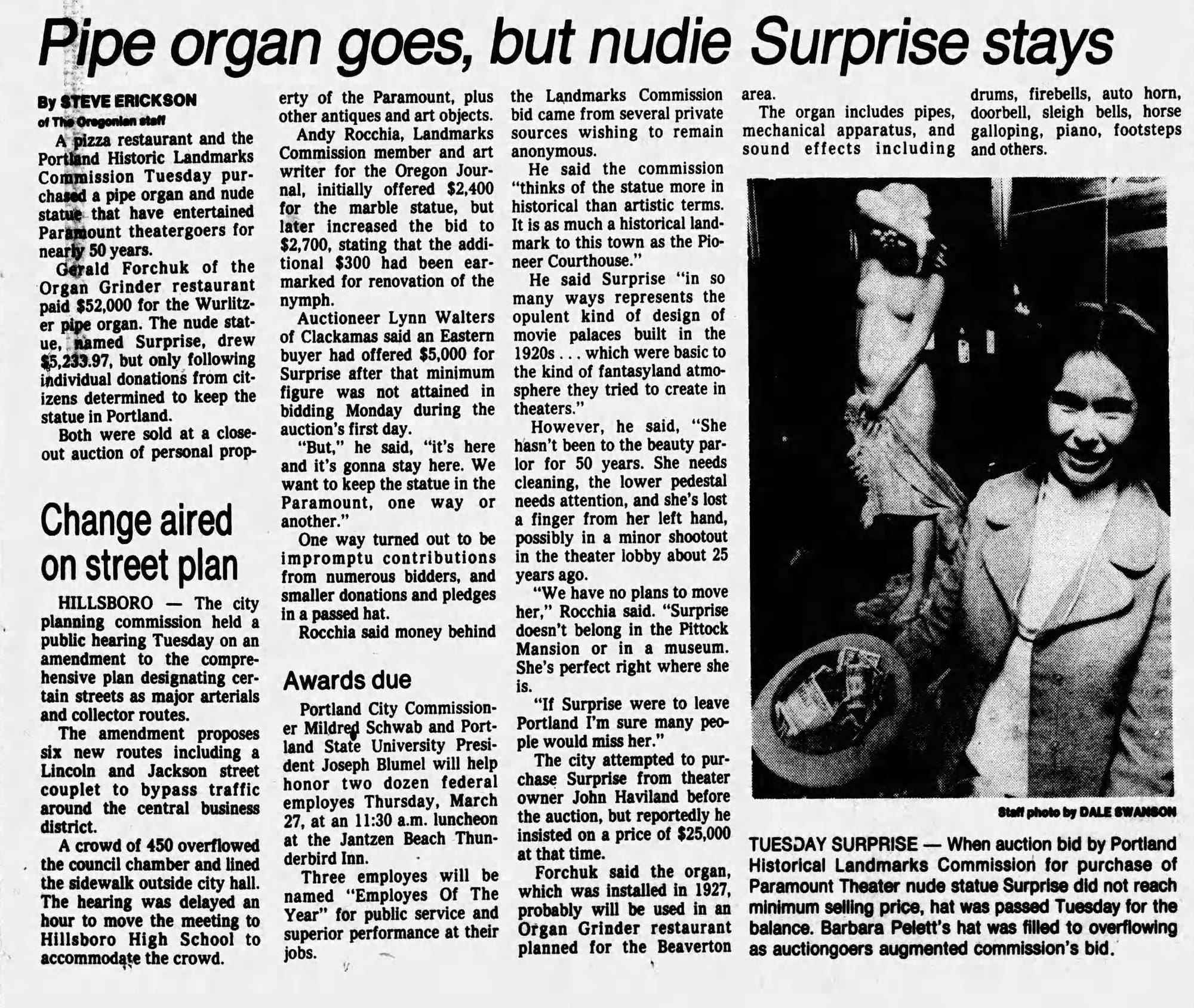

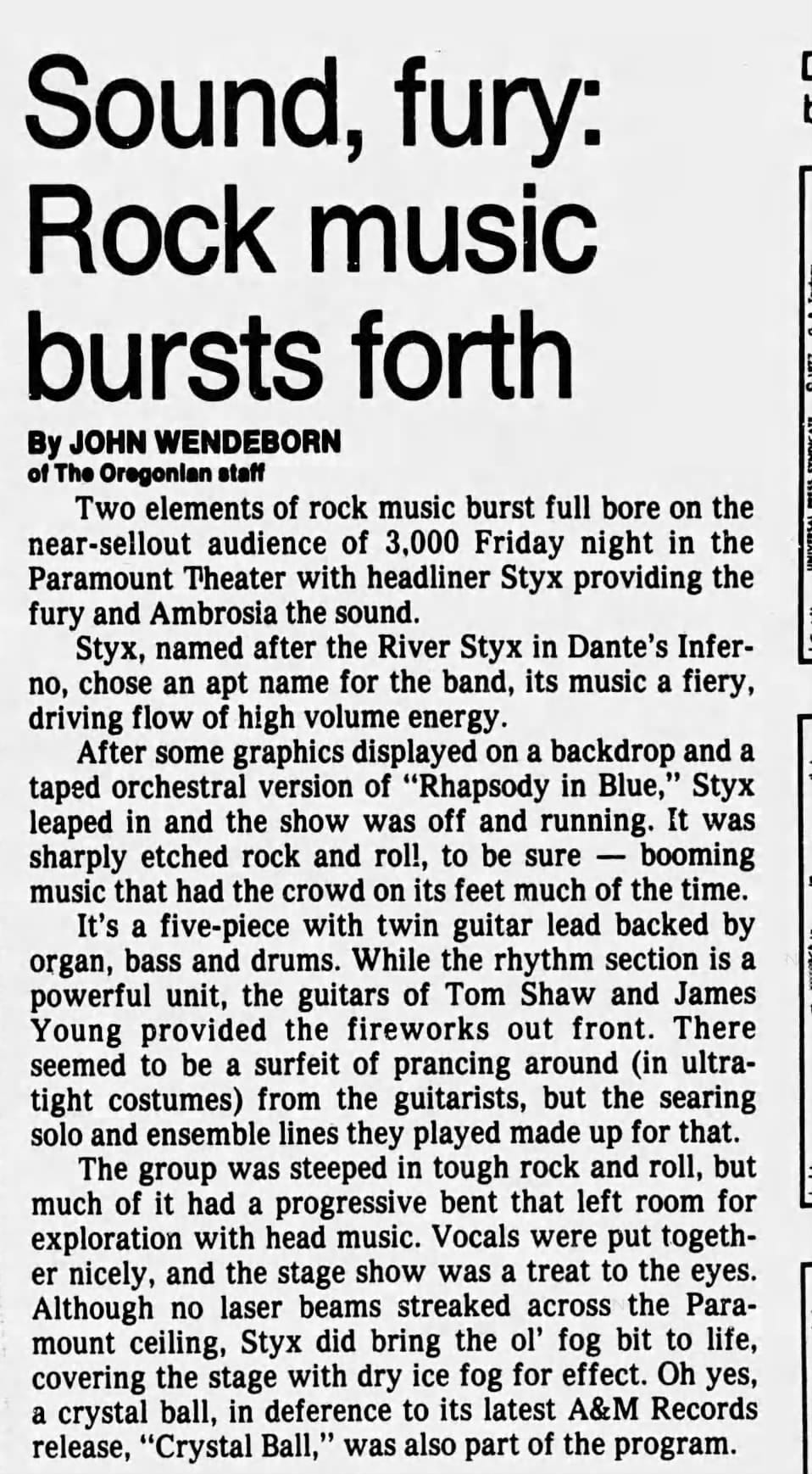

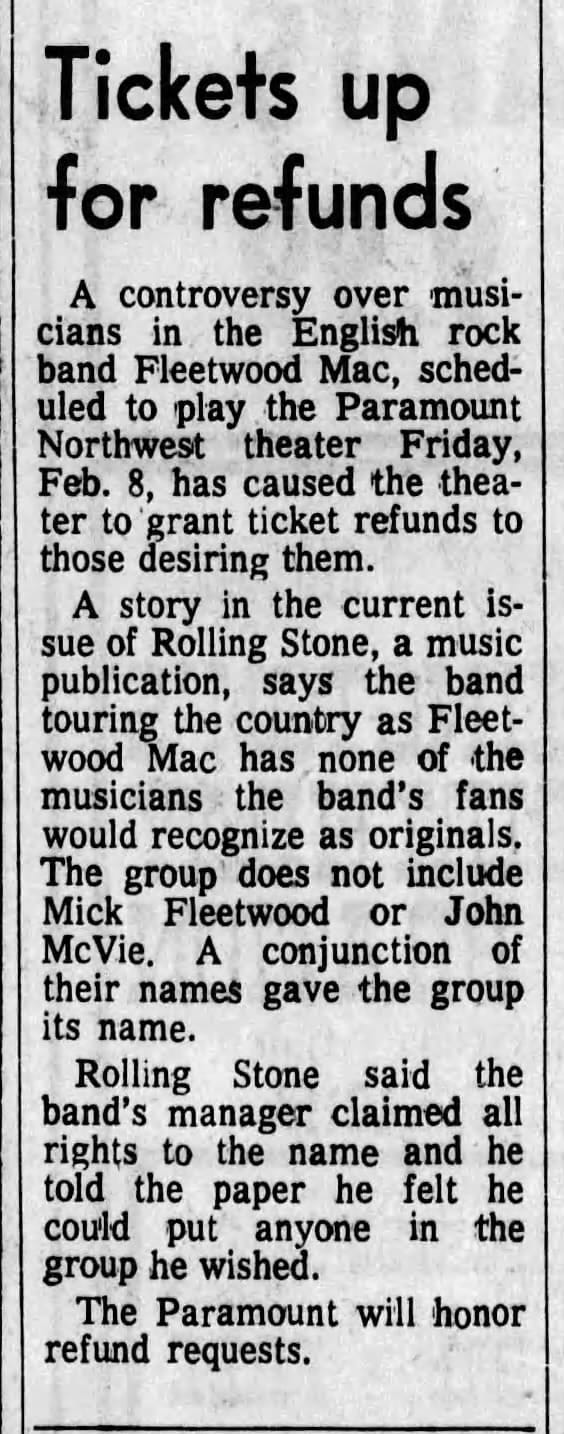

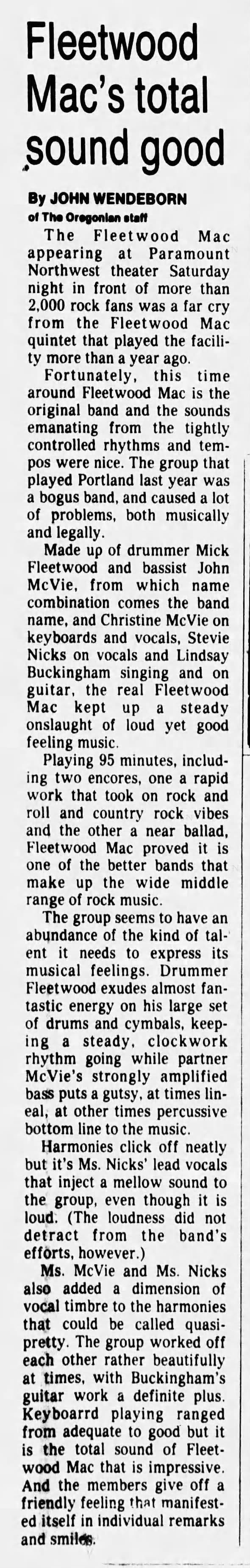

By the 1960s, though, the Paramount Theater was quite literally falling apart—a balcony and part of the facade ended up on the sidewalk in separate incidents. Purchased in 1971, new owner John Haviland wanted to demolish it for a parking lot, but the City of Portland landmarked the exterior in 1972 against his wishes…so in a fit of spite he auctioned off the contents of the interior (which, designed by Armstrong & Powers, was arguably more notable than the exterior). Crumbling and the interior stripped, the Paramount hosted regular rock concerts throughout the 1970s (including both a fake Fleetwood Mac and the real one).

1976, NRHP Nomination Form | 1972 articles on the landmark designation | 1975 articles and ad for the interior auction | 1978 and 1979 articles on fans watching Portland Trail Blazers games at the theater

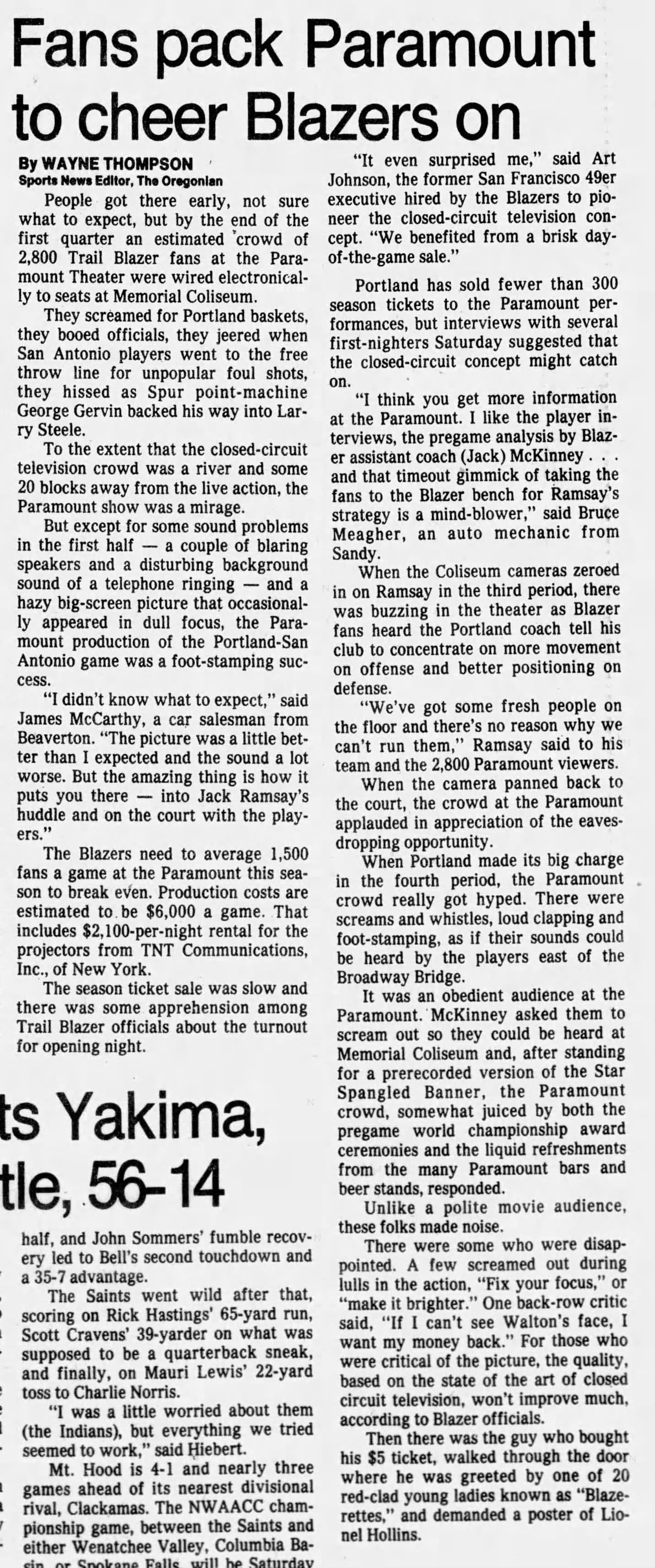

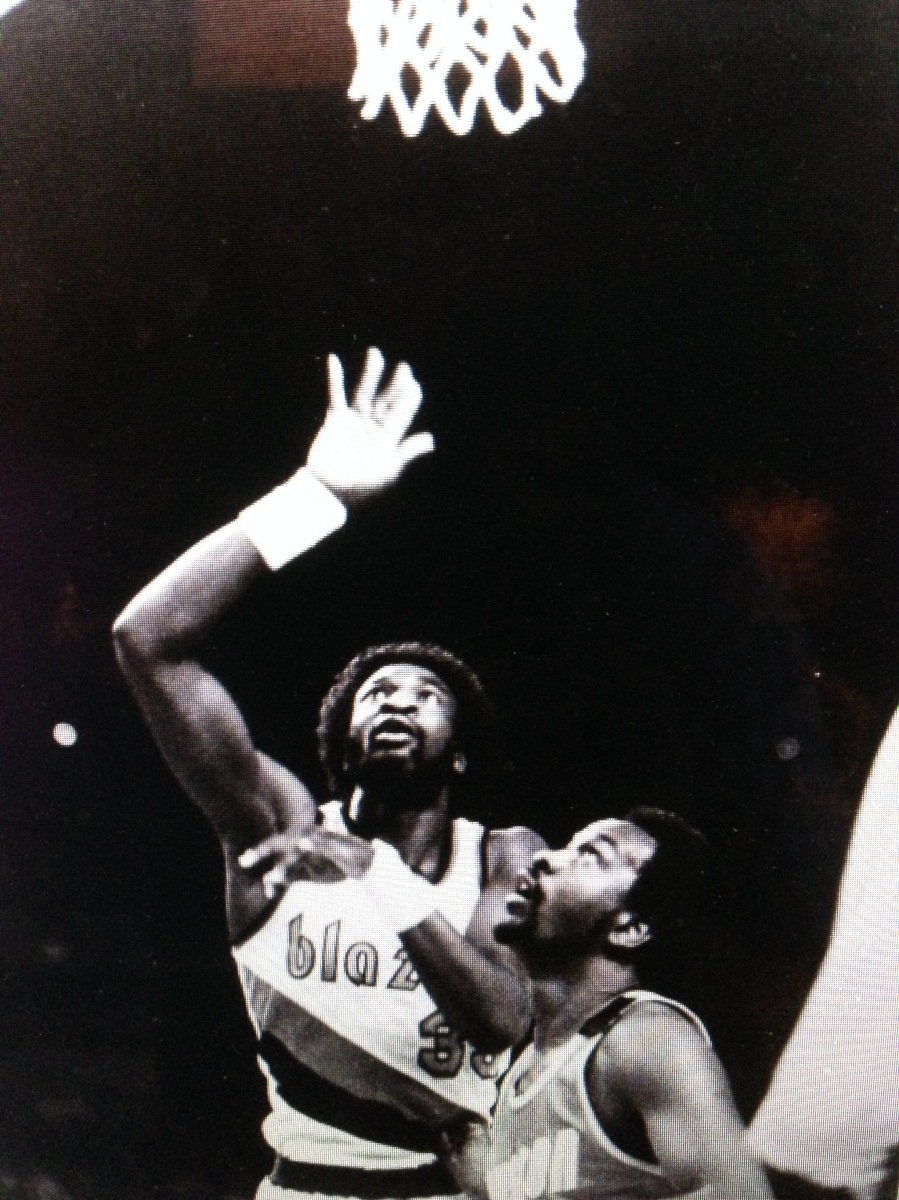

As kind of a quirky, haphazard forerunner to watch parties like the Deer District in Milwaukee, in the late 1970s the Portland Trail Blazers were such a phenomenon that—with the Portland Coliseum constantly sold out—the Paramount screened Blazers games live to overflow crowds. The year after their championship win in 1977, the theater sold more than 2,700 tickets sold per game.

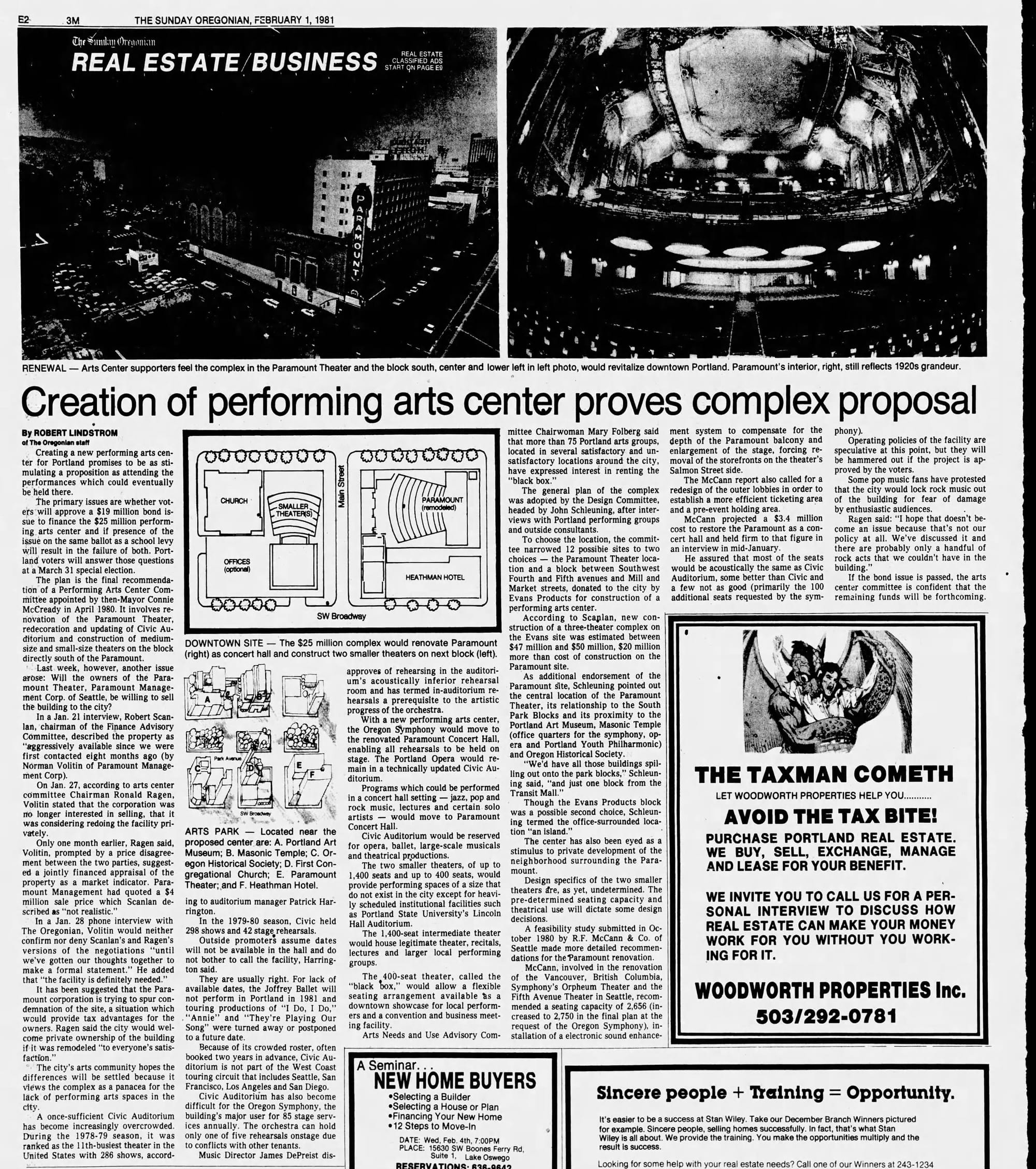

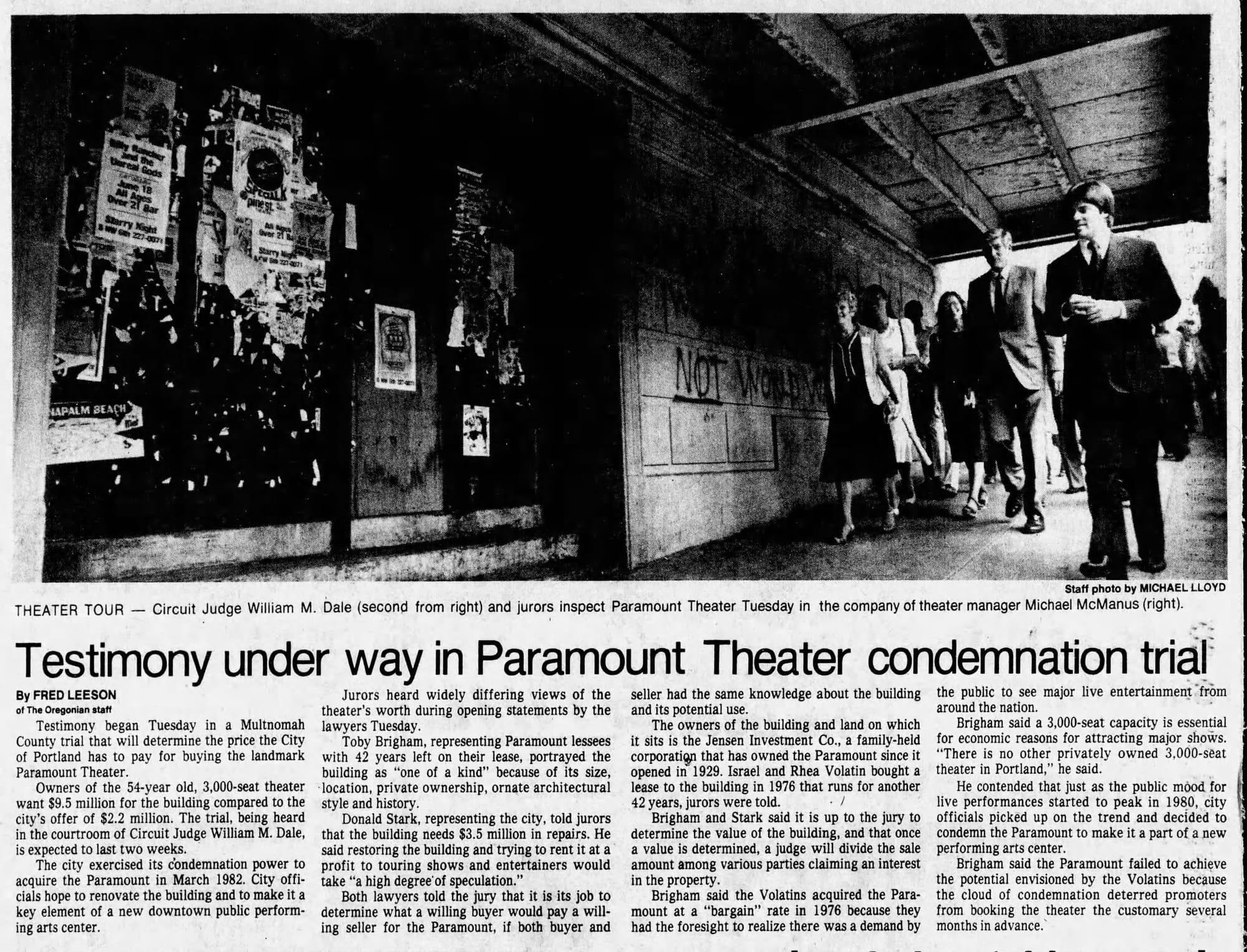

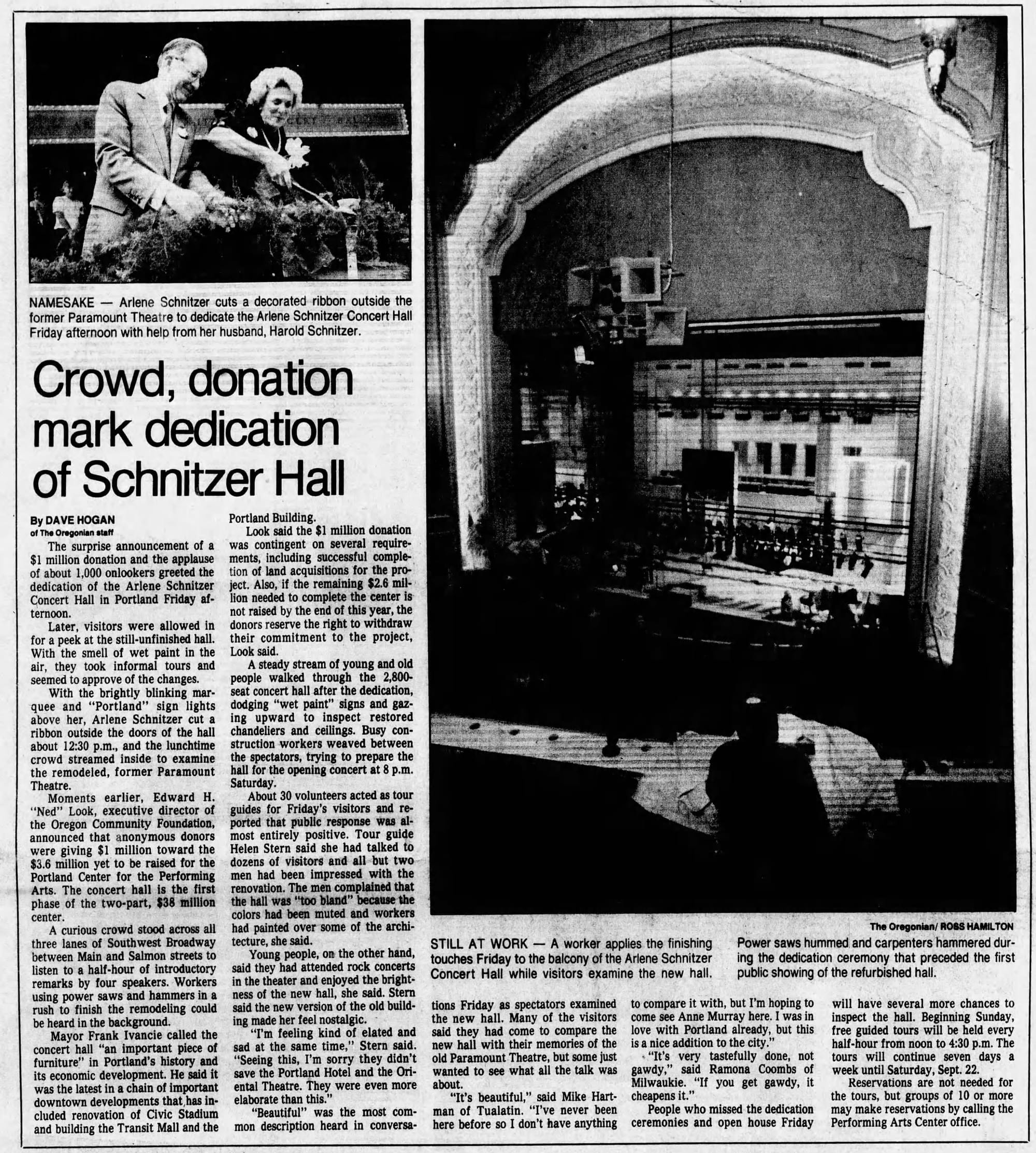

With a capacity of 3,000 seats, even in a dilapidated state the Paramount was the largest theater in Portland. The city zeroed in on its potential to be the heart of a renewed downtown performing arts center, and in 1981 Portland voters approved a $19 million bond levy to construct a four-theater performing arts complex anchored by the Paramount. After negotiations to purchase the theater broke down, the city condemned the building to force a sale and started building the Portland Center for the Performing Arts in earnest.

Early 1980s articles on the theater's conversion into the Schnitzer Concert Hall, the condemnation case, etc. | 2022 photo

Assembling an appropriately broad team for a massive rehabilitation and renovation project, Bora Architects lead the restoration, working with R. Lawrence Kirkegaard, Theatre Projects Limited, ELS Architecture, and Barton Myers. As part of the restoration and conversion, in 1984 they replaced the Paramount sign with a Portland sign that evoked a short-lived original that decorated the building when it opened as the Publix.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and now known as the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, today the 2,776 seat theater is home to the Oregon Symphony, the Portland Youth Philharmonic, the Metropolitan Youth Symphony, the White Bird Dance Company, and Portland Arts & Lectures, as well as various concerts and films.

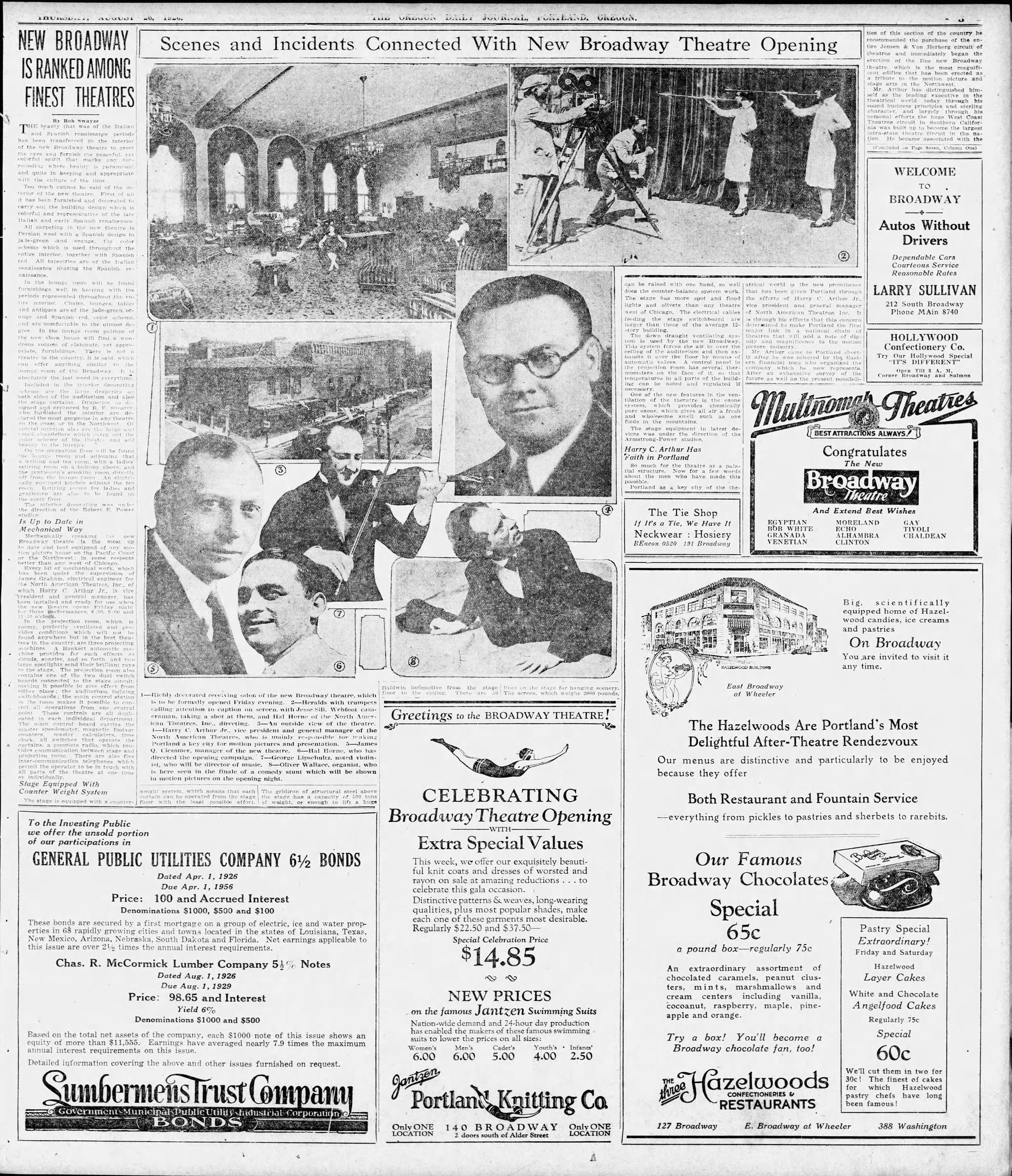

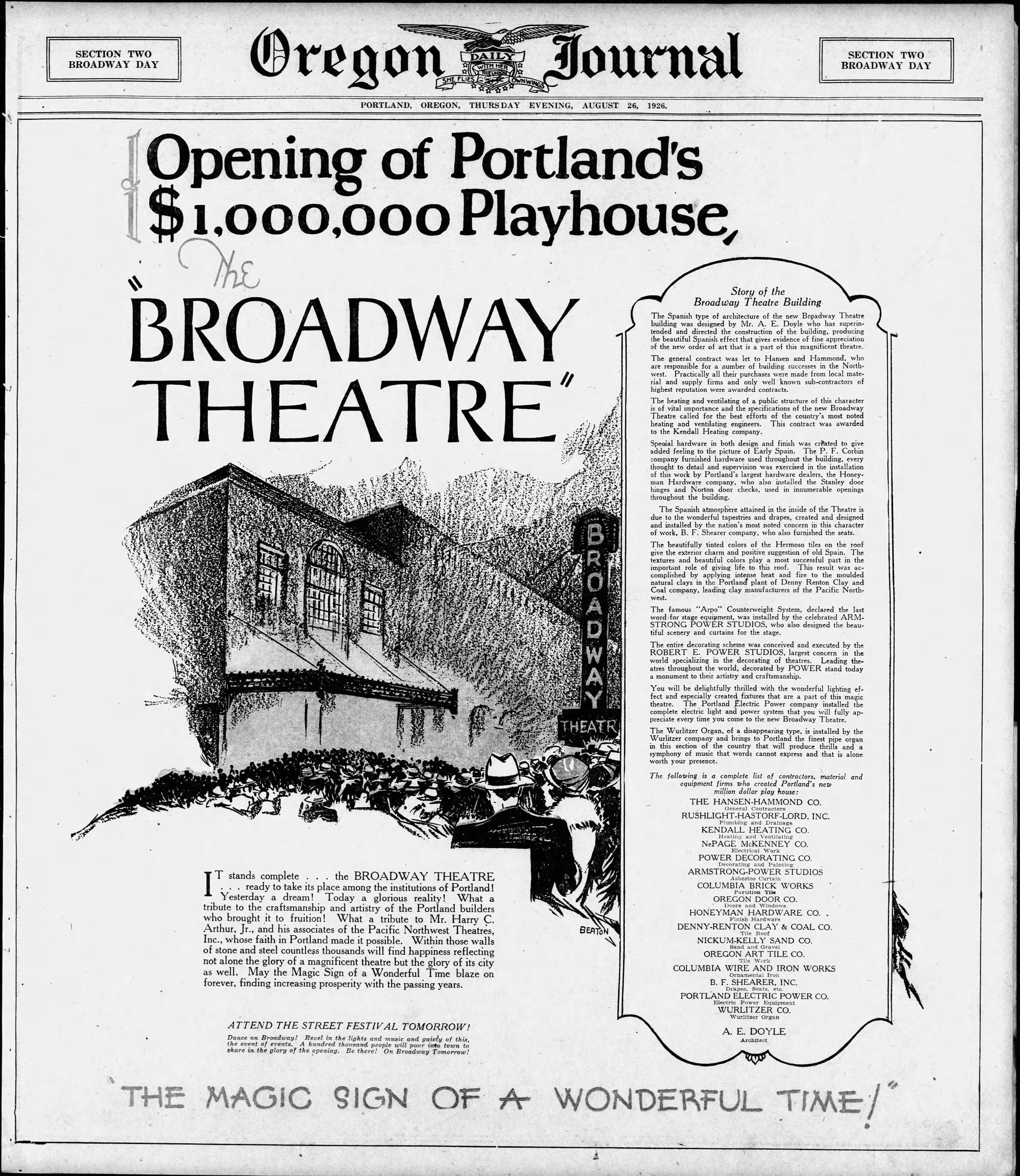

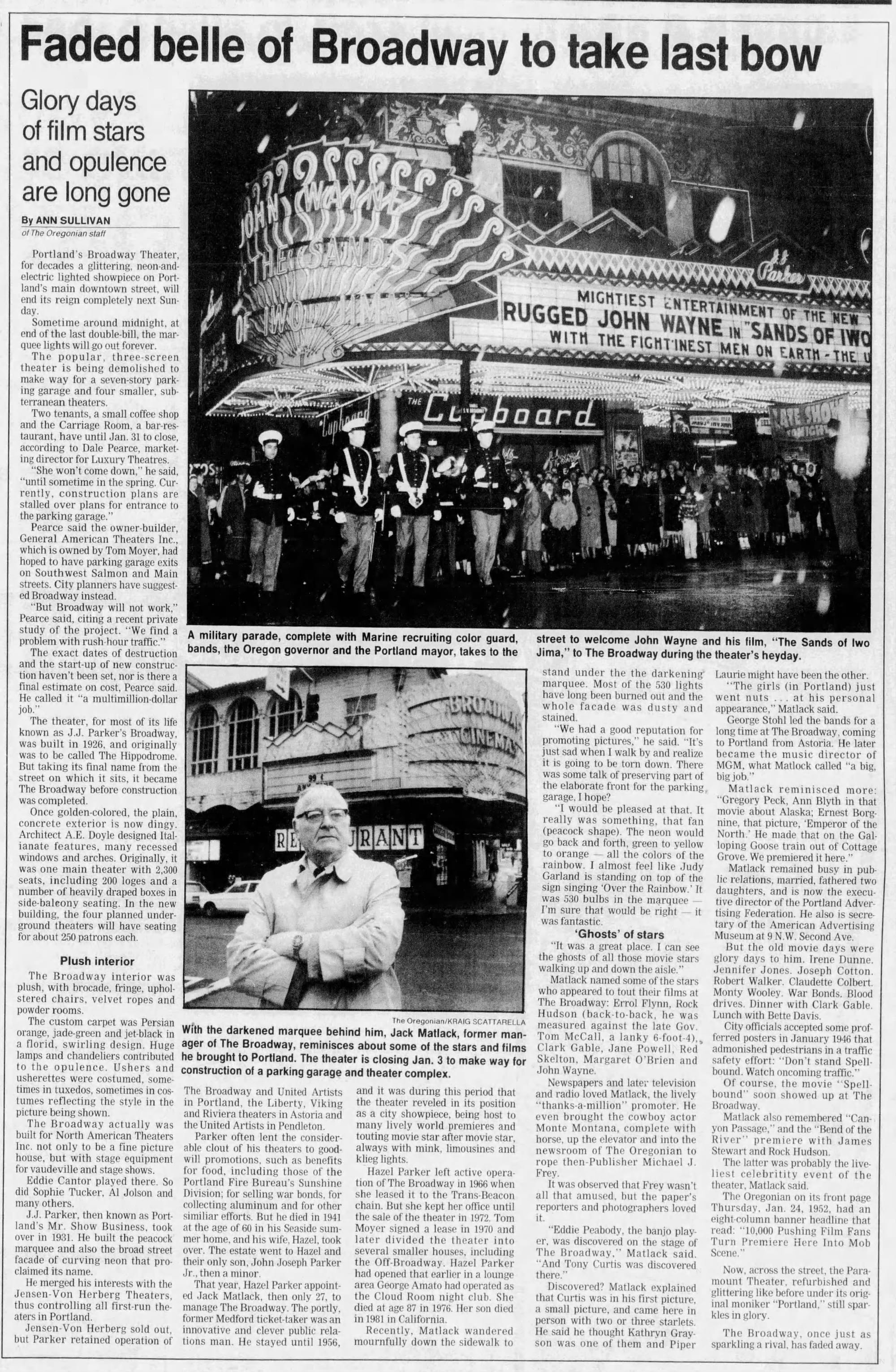

The owners of the Broadway Theatre pipped the Paramount and opened first, in 1926, but it was quickly supplanted as Portland’s largest by its neighbor. Designed by A.E. Doyle’s firm, the theater—sort of a Mediterranean Revival, “Beaux Neon” style—was a bit of an outlier relative to the rest of the prolific Portland firm’s work. Pietro Belluschi, who’d become a highly influential West Coast modernist, worked on the Broadway while he was at Doyle’s firm early in his career.

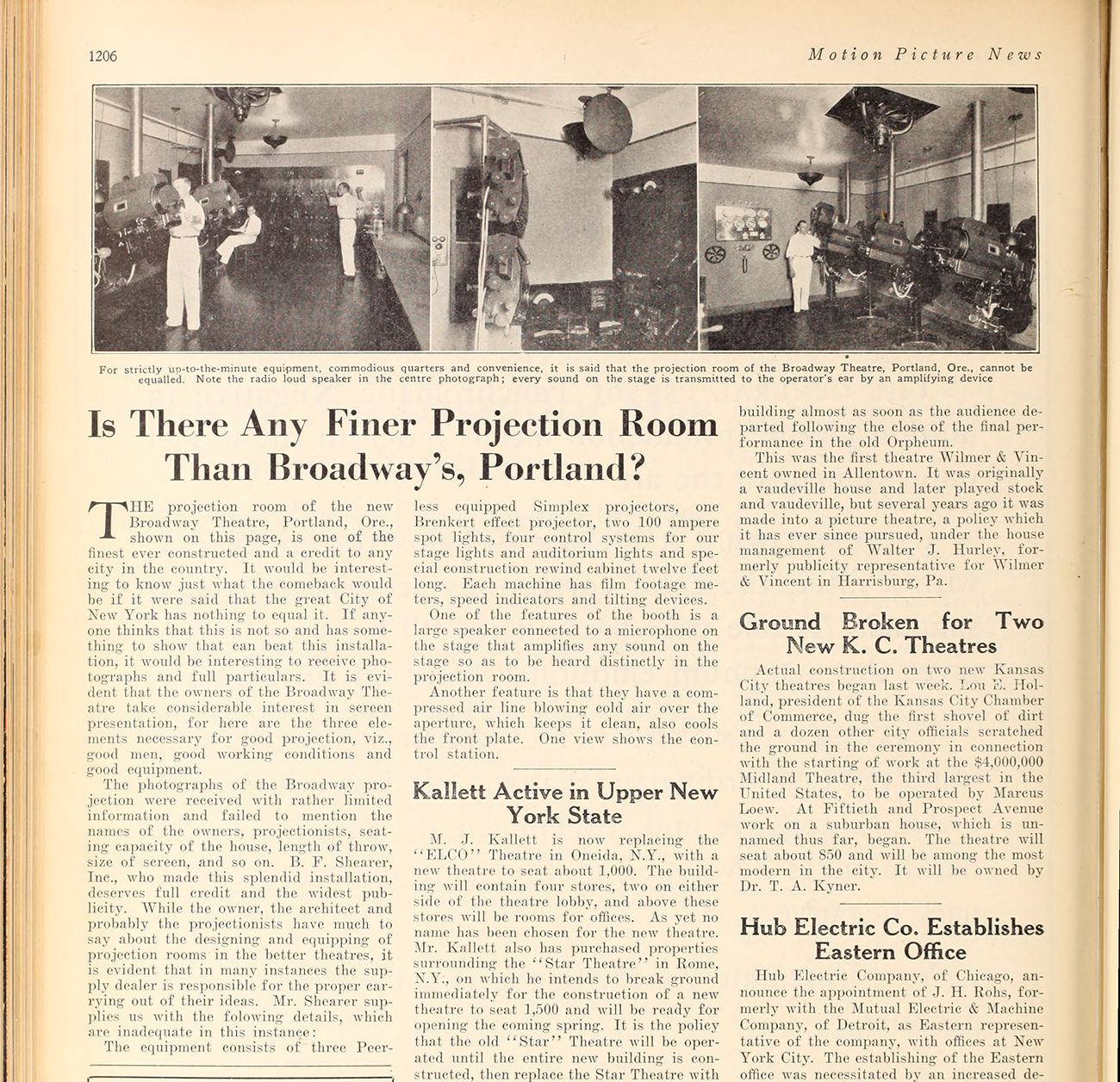

1925 and 1926 articles on plans for the Broadway Theatre and its opening | 1926 article on the Broadway projection room in the Motion Picture News, the Internet Archive | 1926 opening ad | 1950 photo, Oregon Historical Society

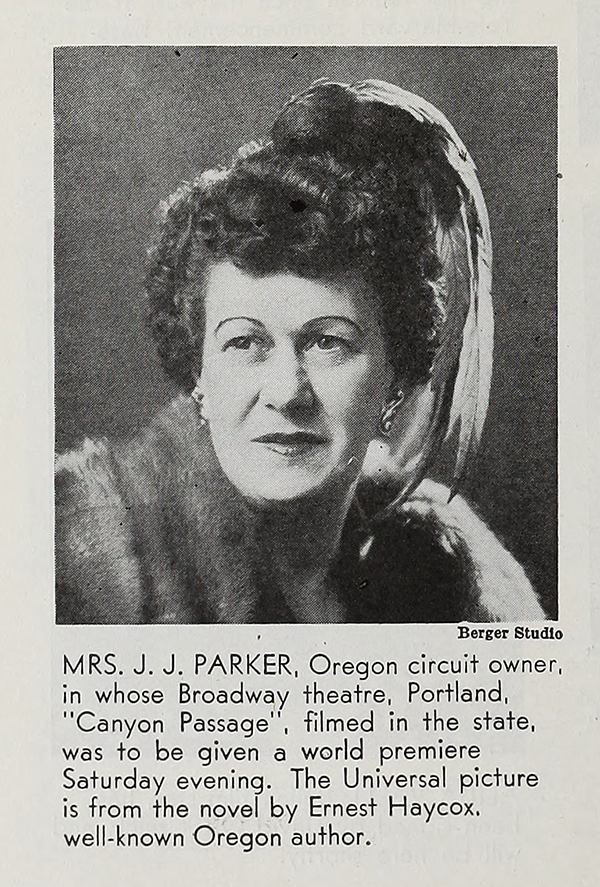

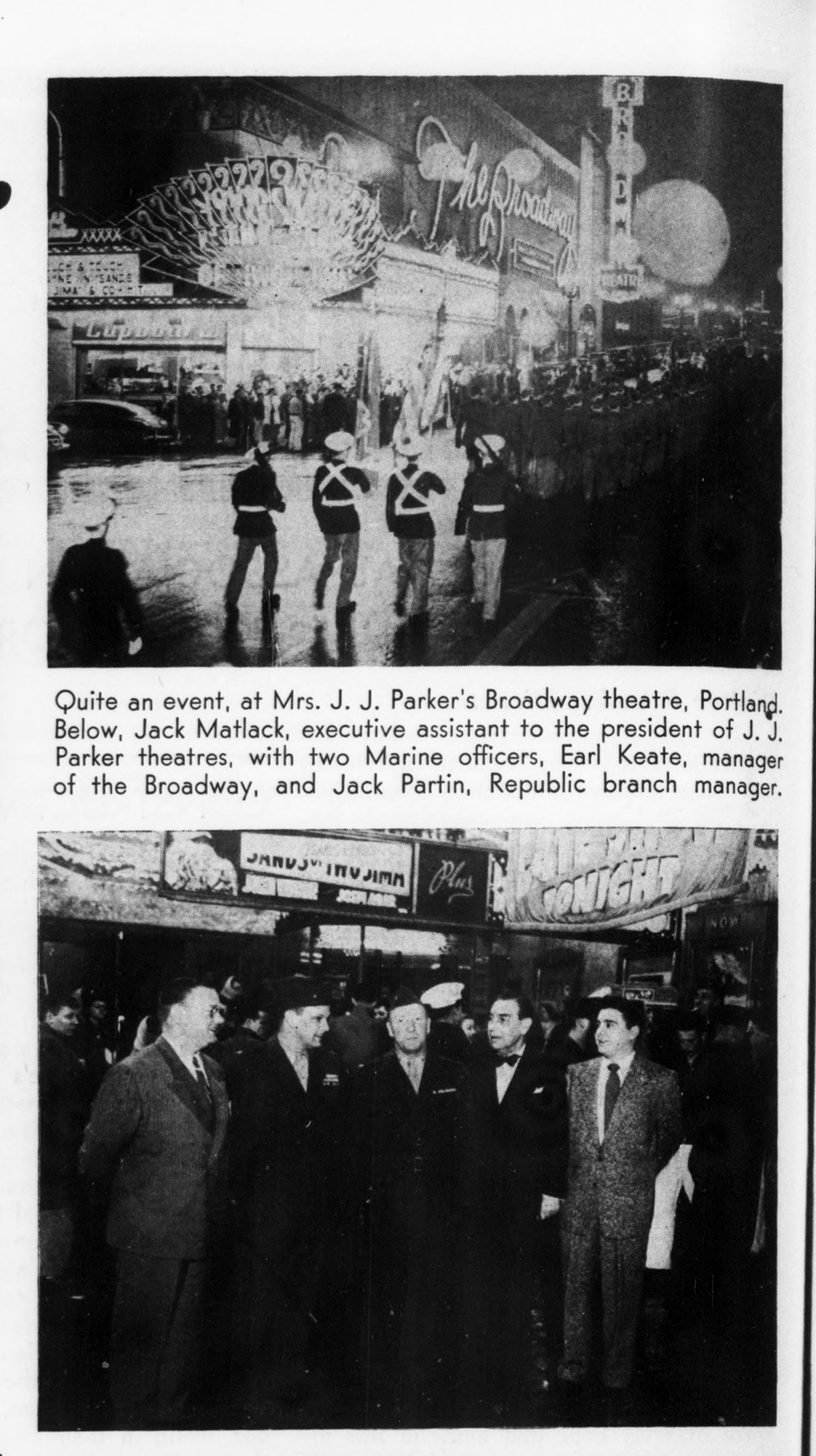

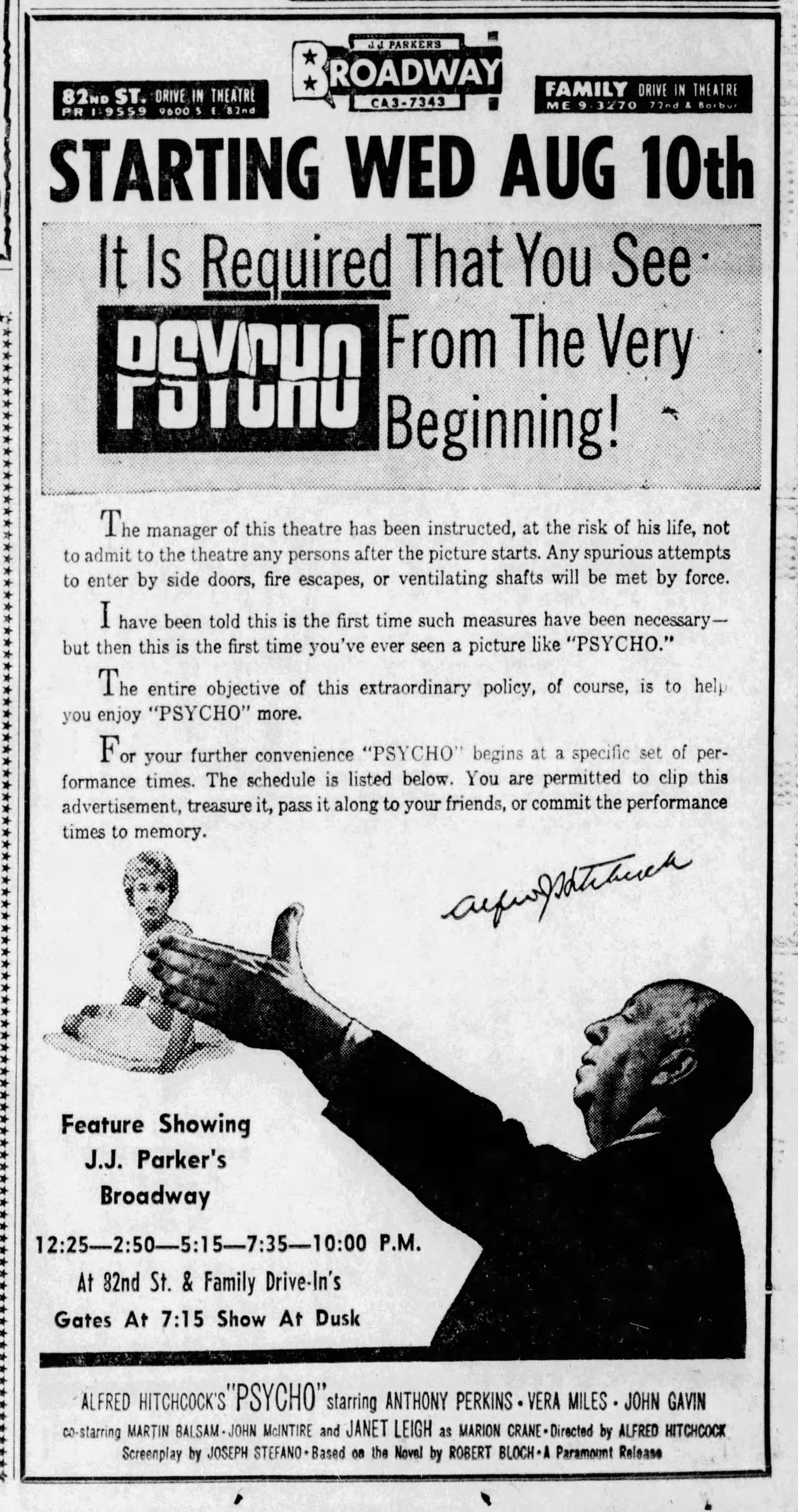

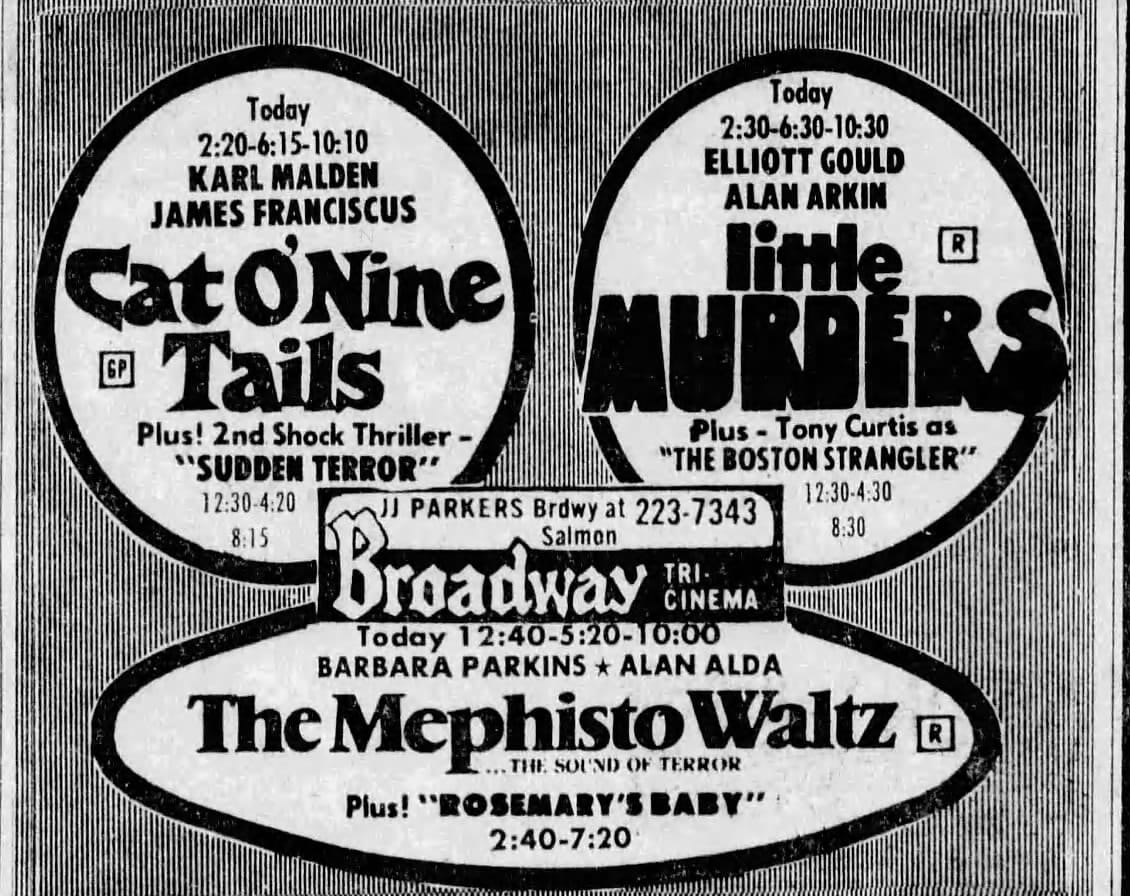

Hazel Parker might’ve been the most noteworthy thing about the Broadway: after her husband J.J. died, from the 1930s to the 1960s Hazel ran the largest independent theater chain in the Pacific Northwest—with this theater, J.J. Parker’s Broadway, the crown jewel. By the 1960s—after the death of Hazel Parker and with the increasing obsolescence of massive, one-screen cinemas—the Broadway was in decline. The theater was remodeled, converting the main auditorium into three smaller theaters and renamed the Broadway Tri-Cinemas.

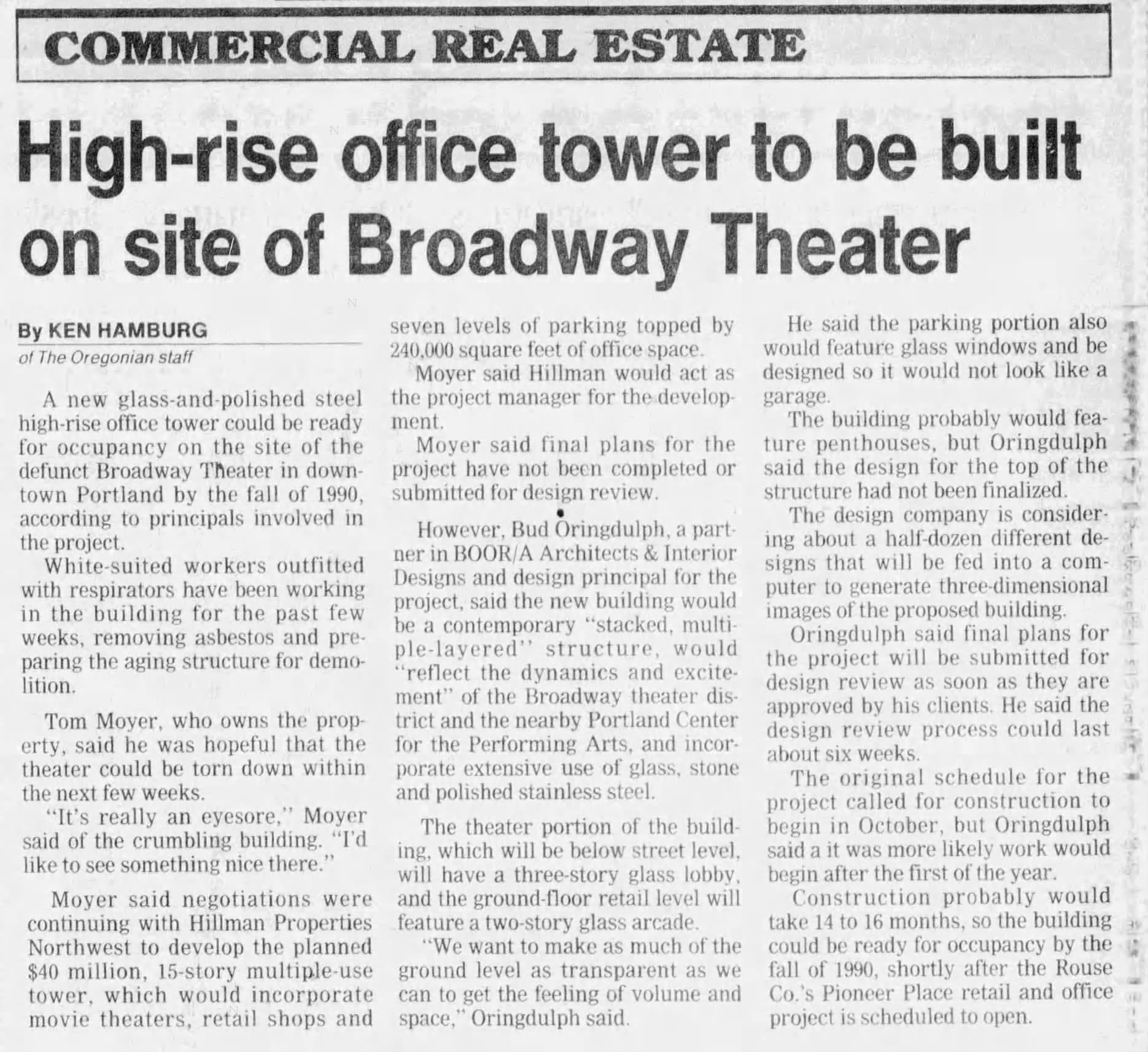

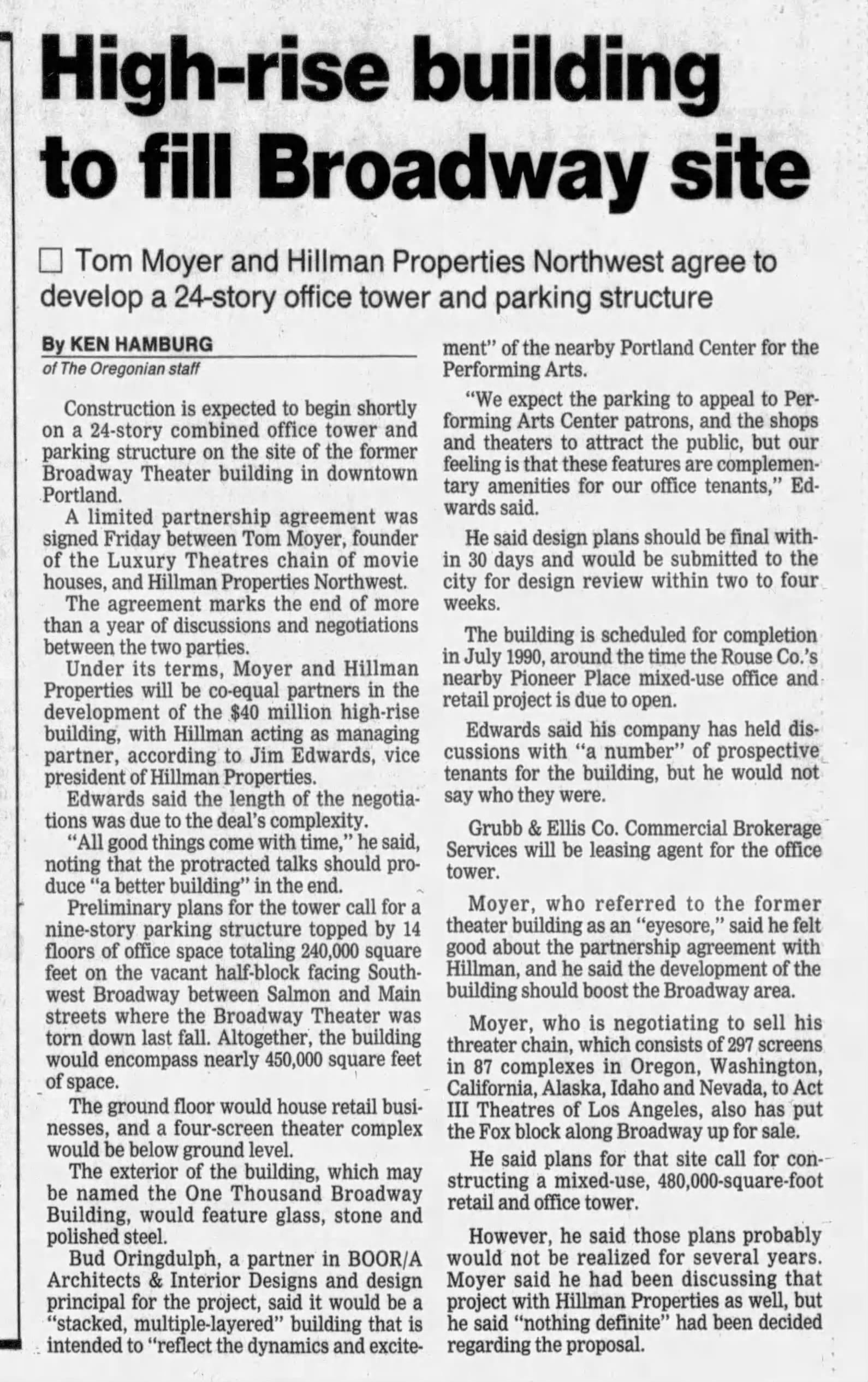

Acquired by PNW cinema tycoon Tom Moyer, whose regional chain had more than 300 screens, in the 1980s at least four serious proposals were considered for the future of the Broadway. Notably, none of them included the survival of the theater. For whatever reason, the Paramount received all the preservation attention as the marquees disappeared from the rest of Broadway.

Hazel Park in the Motion Picture Herald in 1946, the Internet Archive | 1950 article on the opening of the Sands of Iwo Jima at the Broadway in the Motion Picture Herald, the Internet Archive | 1960 ad for Psycho at the Broadway | late 1980s articles on the redevelopment plans and demolition of the Broadway

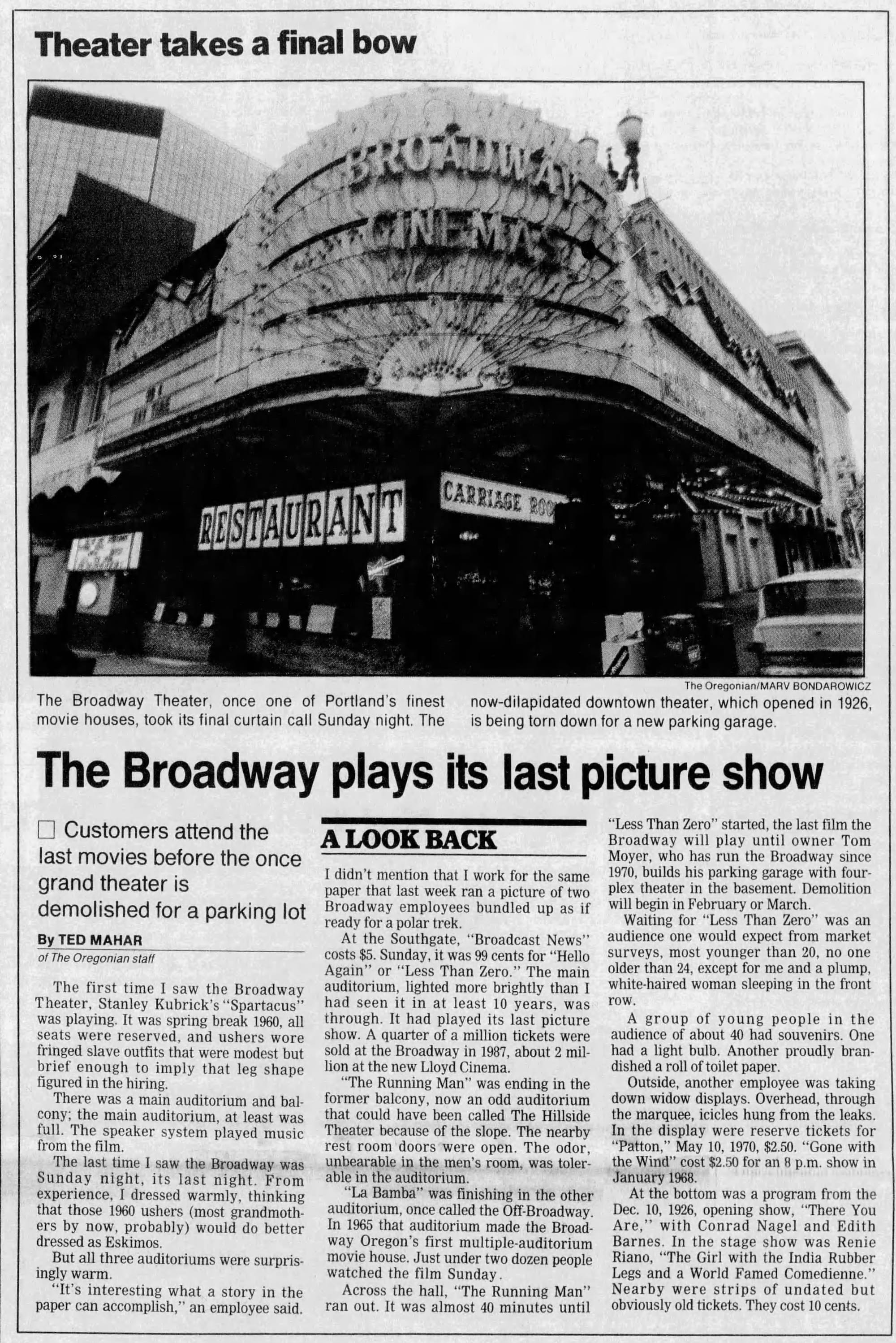

Moyer had the Broadway Theater demolished in 1988—there just wasn’t much need for a massive vaudeville theater awkwardly carved into three movie theaters, across the street from an even bigger performing arts center. Given how even our streamlined theater industry has struggled for the last few decades, I get it—a taller building is probably a more effective use of this land. No city has maintained the density of theaters they had in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s.

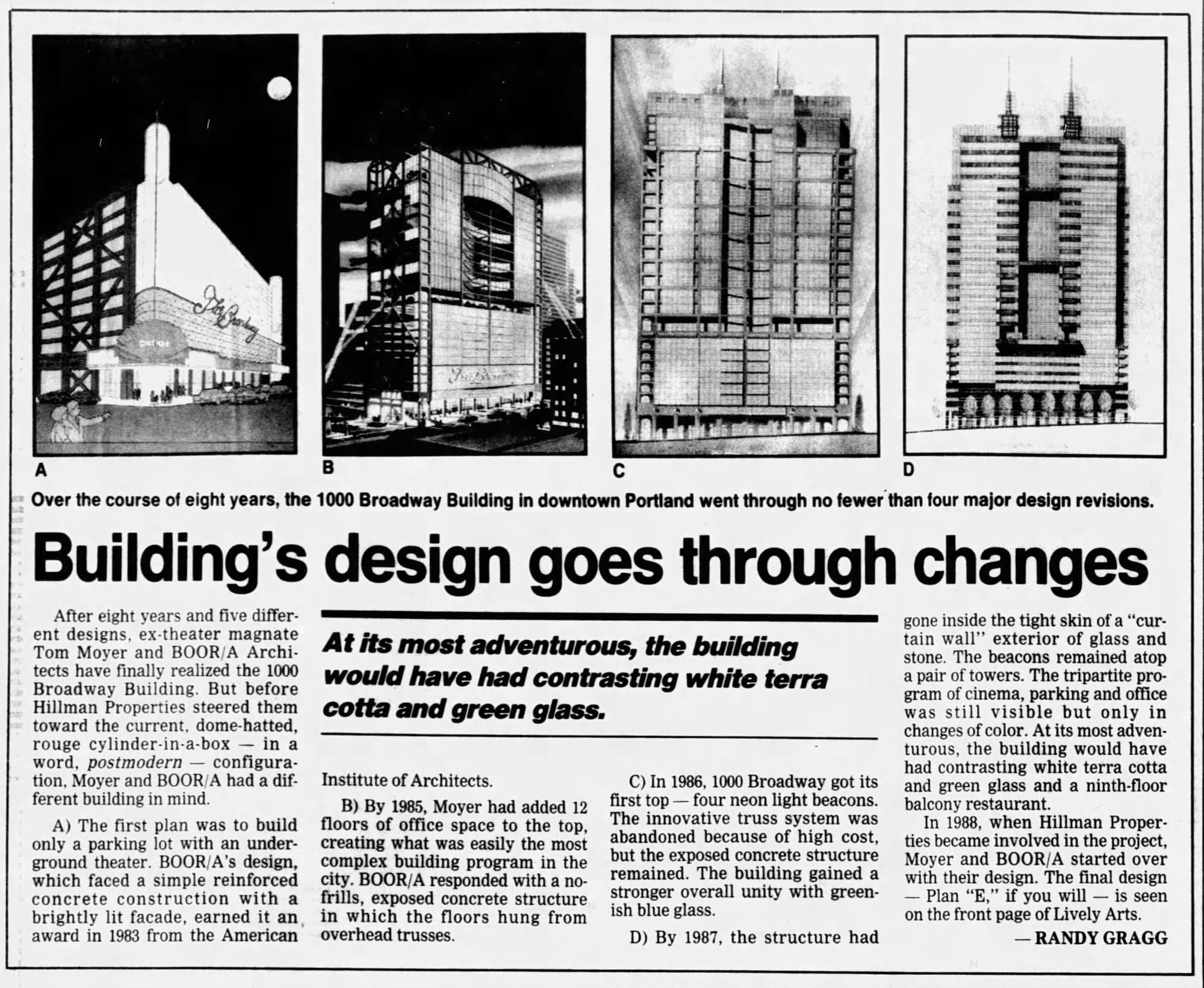

Broome, Oringdulph, O'Toole, Rudolph, and Associates (Bora Architects) designed its replacement, the 24-story 1000 Broadway office building, which opened in 1991. Pink and grey, postmodern as hell, it looks like a stick of roll-on deodorant from afar (it’s nice!). As a slightly hamfisted gesture towards what used to be here, the developer erected an awkward little Broadway marquee on the corner.

Late 1980s and early 1990s articles on the 1000 Broadway office building that replaced the Broadway theater | 1000 Broadway in 2007, Wikimedia Commons | 2022 photo of the Broadway marquee | 1000 Broadway, 1991, Jennifer Millikan, Ball State University Libraries

Although he demolished the Broadway, Tom Moyer clearly just loved movies—1000 Broadway had a four-screen theater in the basement, which closed in 2011. That space is now home to the the Judy Kafoury Center for Youth Arts of the Northwest Children’s Theater, which opened in 2023. Working with SERA Architecture, they converted one of the basement theaters into a 240-seat main stage, one into a 120-seat black box, one into a classroom complex, and left one intact to show second-run family films.

So, after all that—all the marquees of Portland’s Broadway blinking out for the final time—this specific block of Broadway actually supports the same amount of theaters as it did in the 1930s. Two.

…they’re just a bit different than the gargantuan movie palaces of yore.

1935, City of Portland Archives | 1950, City of Portland Archives | 1965, City of Portland Archives

Production Files

Further reading:

- Frozen Music: A History of Portland Architecture by Gideon Bosker and Lena Lencek

- Paramount Theatre NRHP Nomination Form

- Heathman Hotel NRHP Nomination Form

- Some great photos in this Puget Sound Theatre Organ Society post

- Auction catalog from the 1975 sale of the Paramount's interior

The papers were stoked about the pre-cast work involved in building the Paramount, as well as the decorations by noted theater designer Robert E. Powers on the Broadway (he also did the interiors of the Paramount)...but they were worried that Portland couldn't support this many seats.

1920s articles about the construction and decoration of the Paramount and Broadway theaters

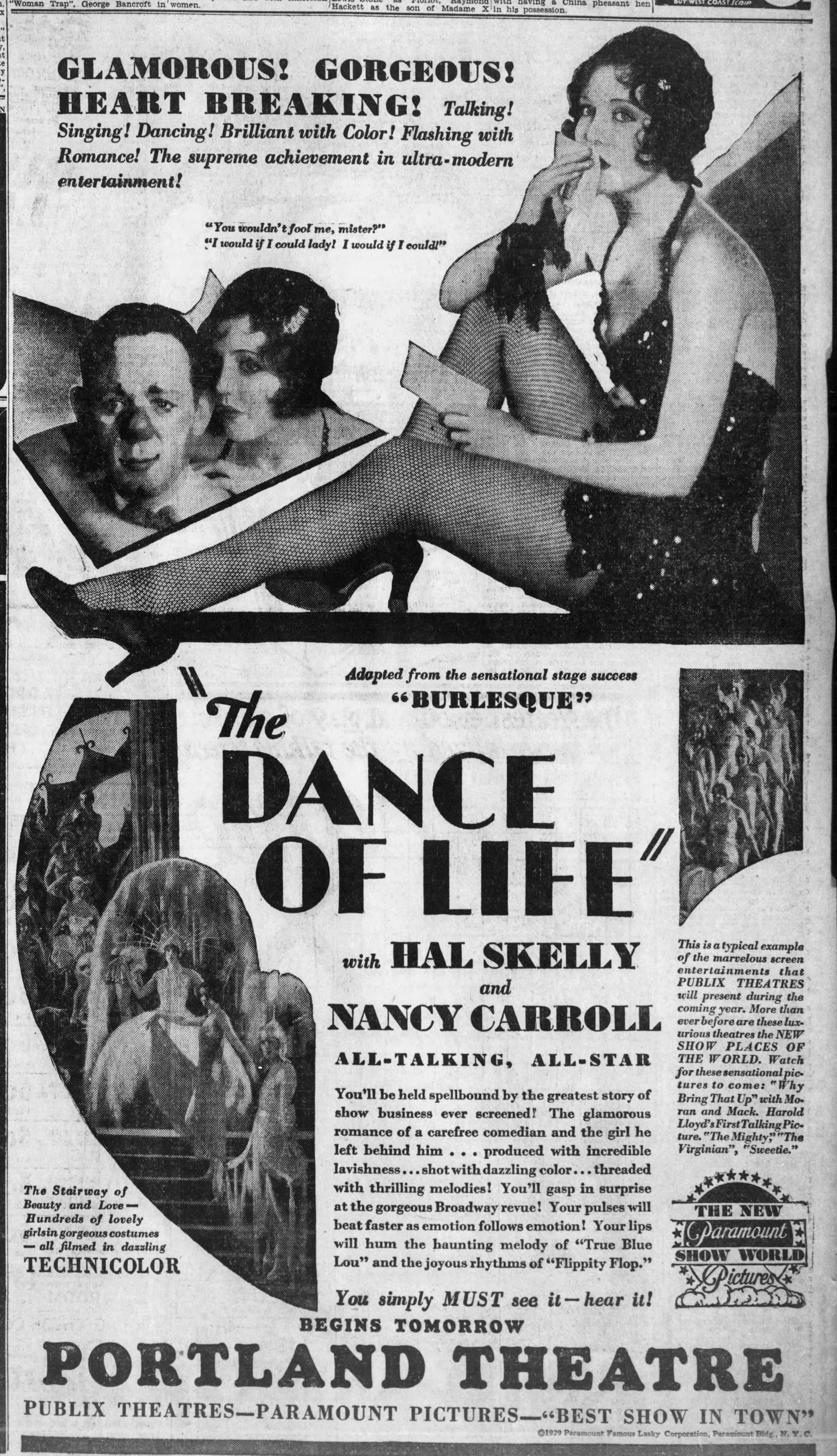

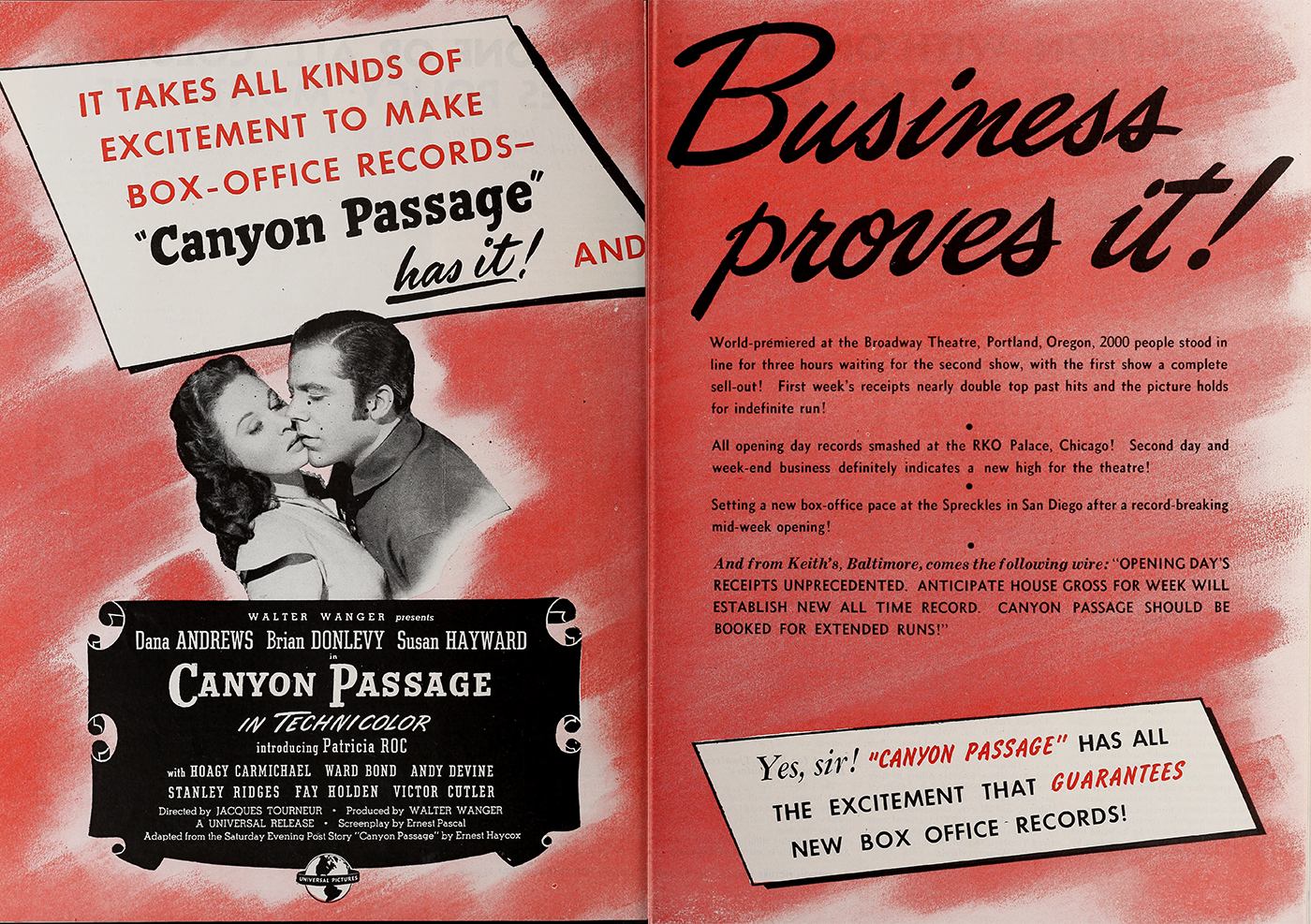

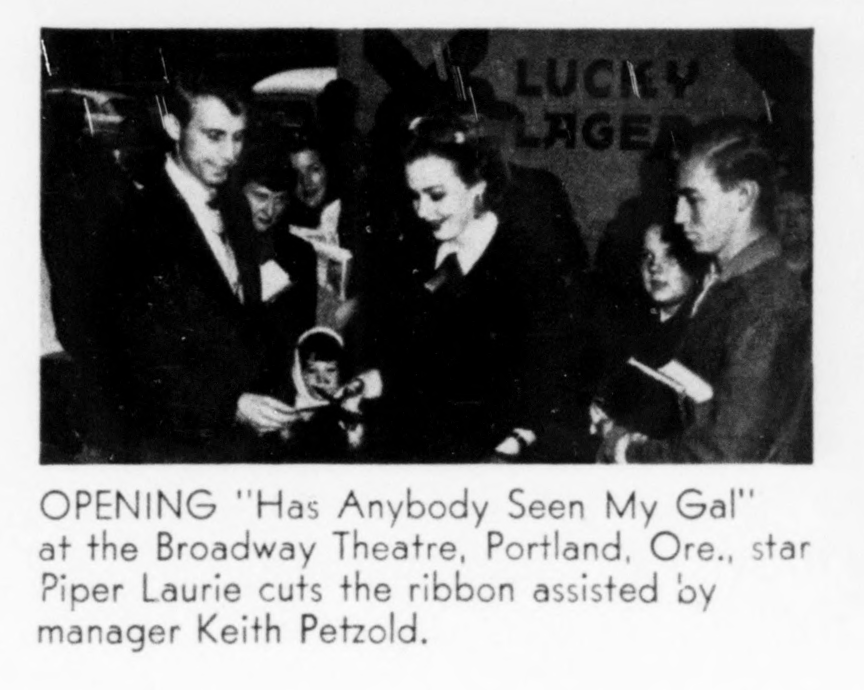

Some movie ads for both theaters.

Various ads for films at the Paramount and Broadway

The Paramount also hosted rock concerts throughout the 1970s...including a fake Fleetwood Mac tour in 1974.

1970s articles about rock concerts at the Paramount

Member discussion: