The first public museum in Denmark when it opened in 1848, Thorvaldsens Museum is my favorite kind of these posts–one that changes my mind a little bit. I still think handing over prime public land in perpetuity for a single-artist museum or an oligarch’s pet project is incredibly shortsighted–imagine the hubris to believe you know what will be relevant a century later–but Thorvaldsens Museum is pretty unique. The culmination of a project to turn sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen into a national icon for the emerging Danish nation-state–Thorvaldsen as a sort of Danish demigod with this museum-tomb as his pantheon–this is a distinctive example of national mythmaking, architectural innovation, and adaptive reuse.

First things first: what’s changed? When it comes to Thorvaldsens Museum itself…basically nothing?!

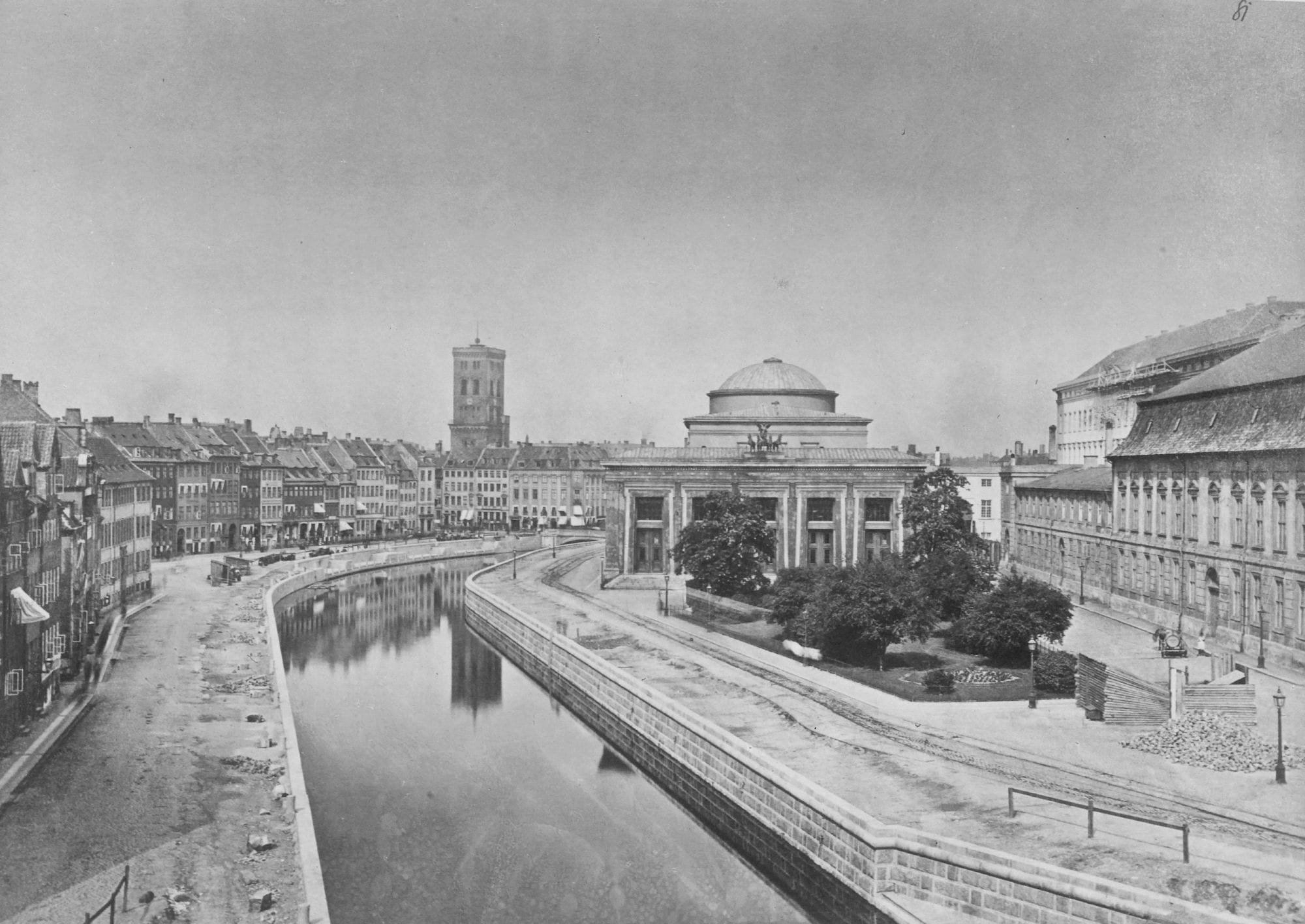

The frieze on the exterior was repainted in the 1950s and the interior has been rearranged a bit (perhaps most controversially, electric lighting was added in the 1920s), but otherwise architect Gottlieb Bindesbøll would recognize this building as the one he designed. The real change is the spire that sprung up behind the museum, part of Christiansborg Palace. Like most of Copenhagen, the seat of the Danish Parliament isn’t as old as you’d think; the second Christiansborg Palace burned down in 1884, and this postcard dates to the period the third Christiansborg (...hopefully the final one) was being built (it was finished in 1928). Oh, and the city added a ladder into the canal.

That out of the way and backing way up…who the hell was Thorvaldsen and why does he have a museum? A neoclassical sculptor (for a few decades the neoclassical sculptor), Bertel Thorvaldsen was the most famous Dane in the world in the early 1800s. Based in Rome, he was a rival and eventual successor to Antonio Canova. Thorvaldsen was so big that the Vatican even commissioned him–a Danish Protestant–to sculpt the tomb of Pope Pius VII.

Ganymede with Jupiter's Eagle, Bertel Thorvaldsen, photography by Carsten Norgaard, Wikimedia Commons | 1840 daguerrotype of Bertel Thorvaldsen, Aymard Charles Théodore Neubourg, Wikimedia Commons | Bertel Thorvaldsen with the Bust of Horace Vernet, painted by Vernet in 1833, Wikimedia Commons | Pope Pius VII tomb in Saint Peter's Basilica, sculpted by Thorvaldsen, photographed by Gunnar Bach Pedersen, Wikimedia Commons

With an eye to his personal legacy, Thorvaldsen planned to give his collected works to whichever city built him a museum, with Munich, Stuttgart, & Copenhagen in the mix. I gotta imagine Copenhagen always held the advantage–not only was it Thorvaldsen's birthplace, but he had already bequeathed his personal art collection to the city in 1830 (that is, the art he collected, not the art he made).

Thorvaldsen and his elite patrons undoubtedly thought a dedicated museum would secure the sculptor’s legacy for eternity. However, the humbling irony is that over the next century your Rodins, Giacomettis, Moores, Nevelsons, etc. all came along, and Thorvaldsen's style of technically-accomplished, highly formal neoclassical sculpture fell out of fashion–internationally, he’s pretty obscure today.

At the height of Thorvaldsen's fame, in the first decades of the 1800s, though, the monarchical states of Europe were struggling with the rise of liberalism and nationalism. One response by the Danish elite to those pressures was this museum, a public monument to an idealized Danish hero. As much a Grundtvigian nation-building project as it was a museum, Thorvaldsen the man and Thorvaldsen’s art were tools to create and spread a Danish national consciousness.

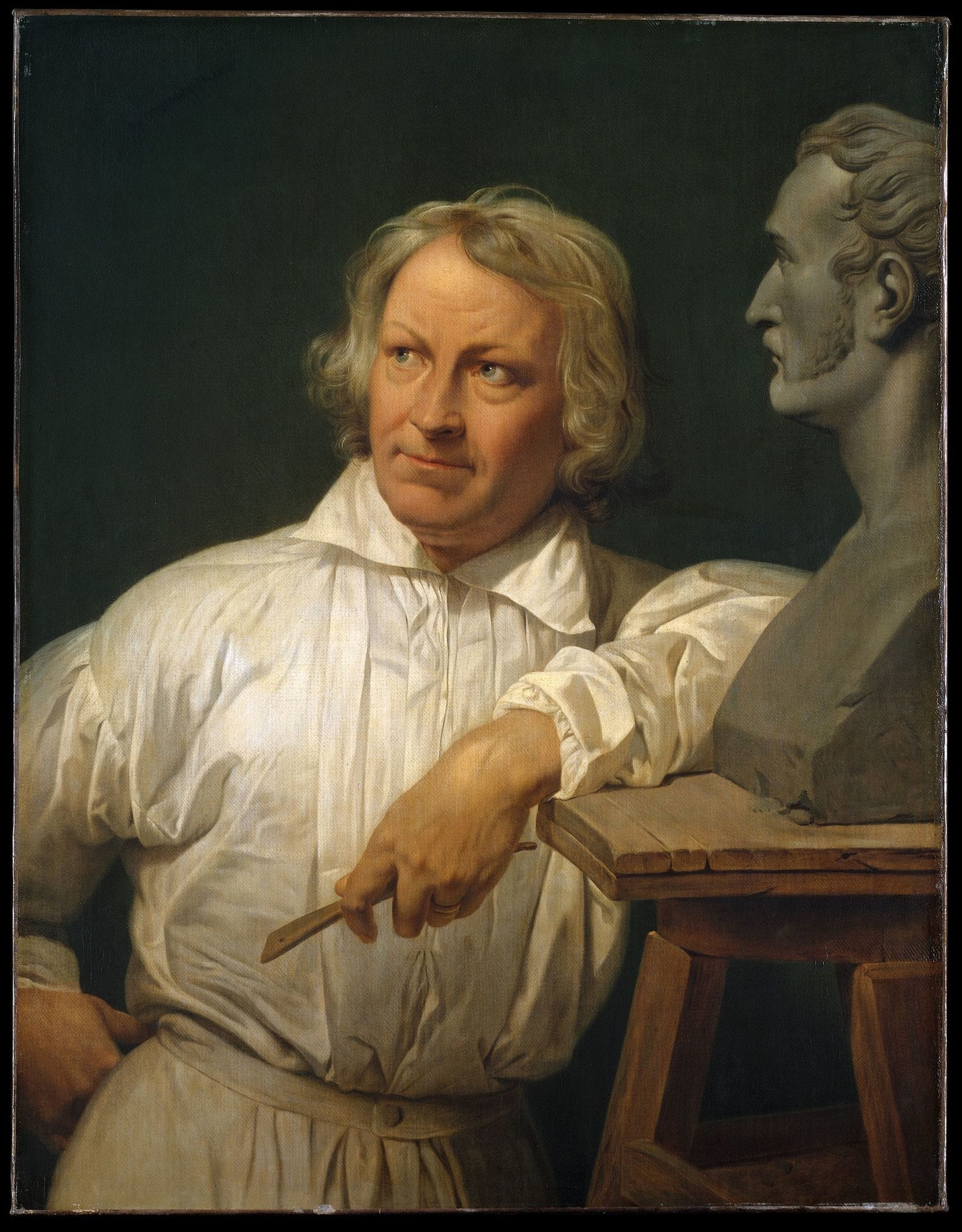

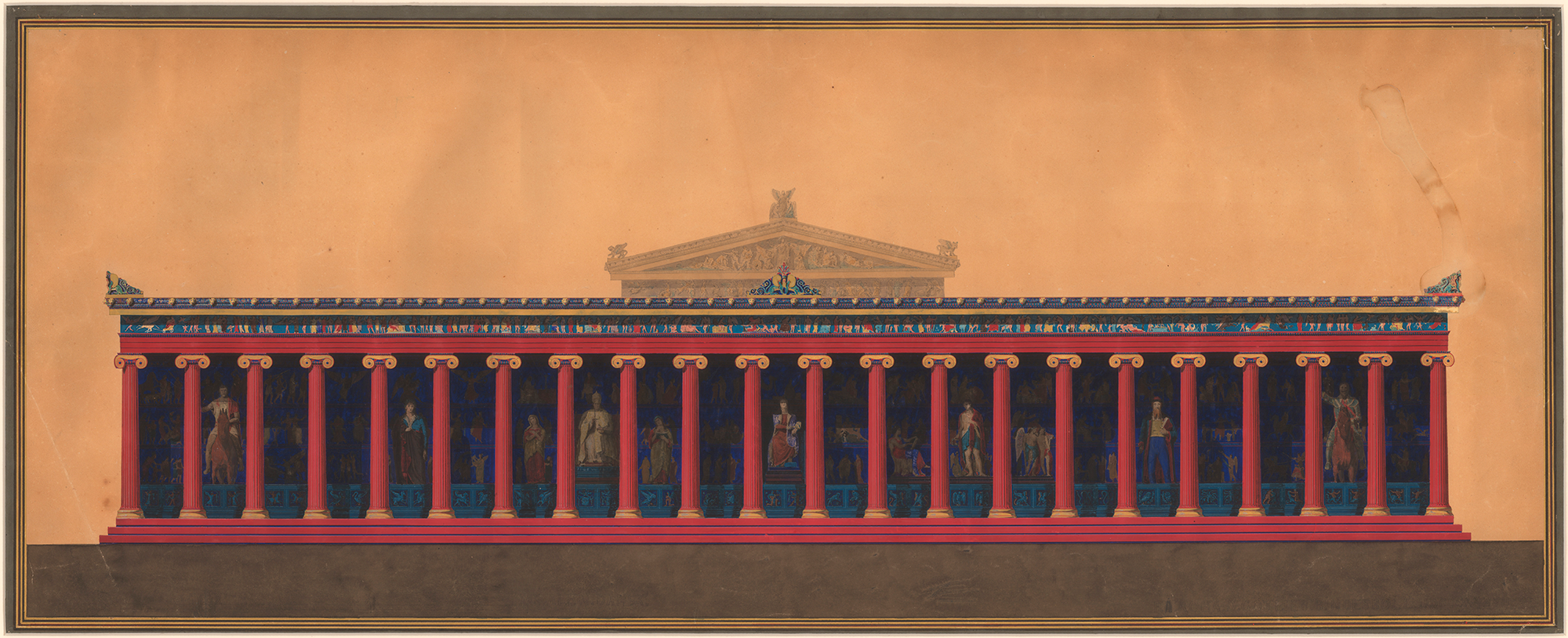

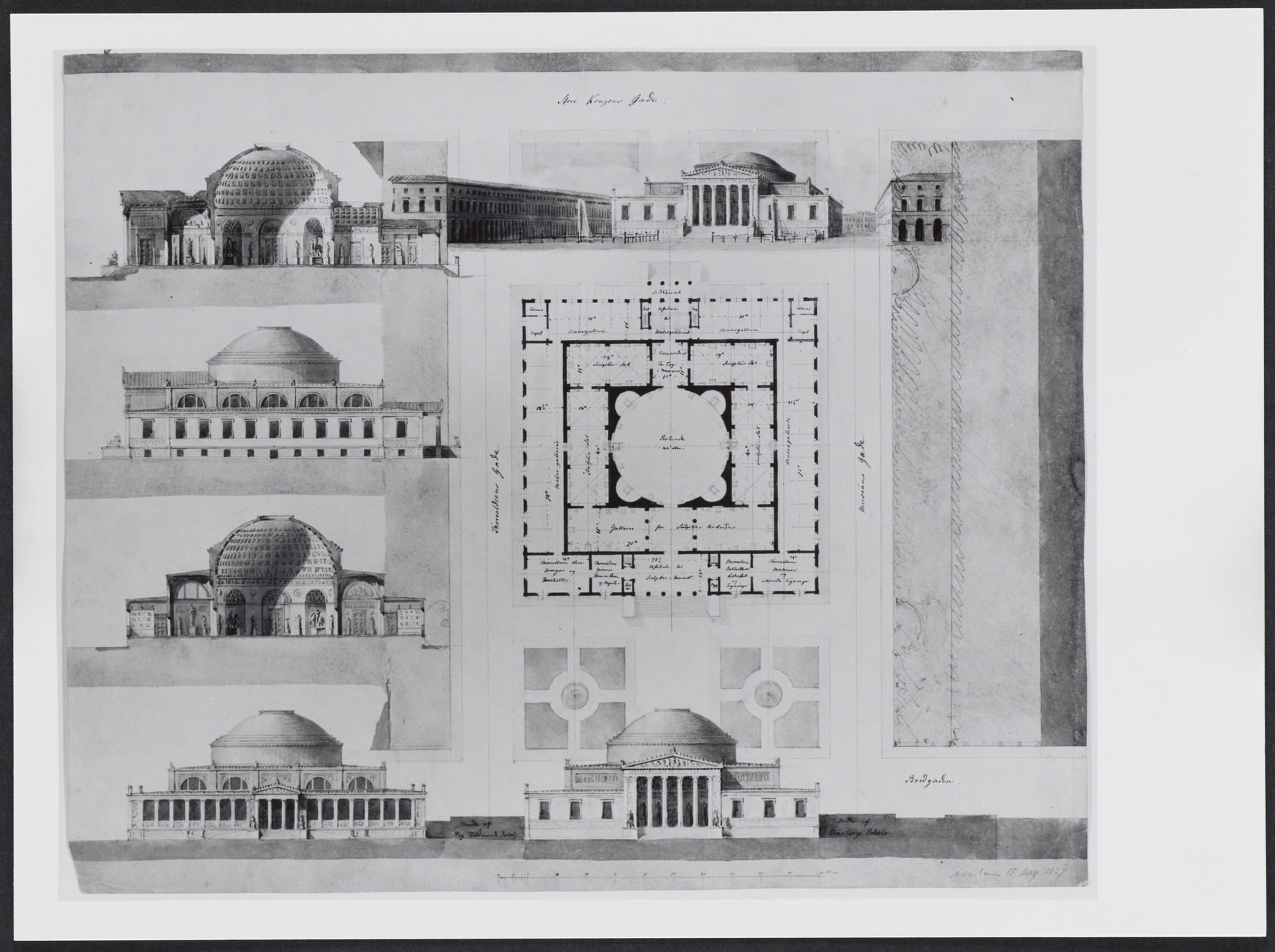

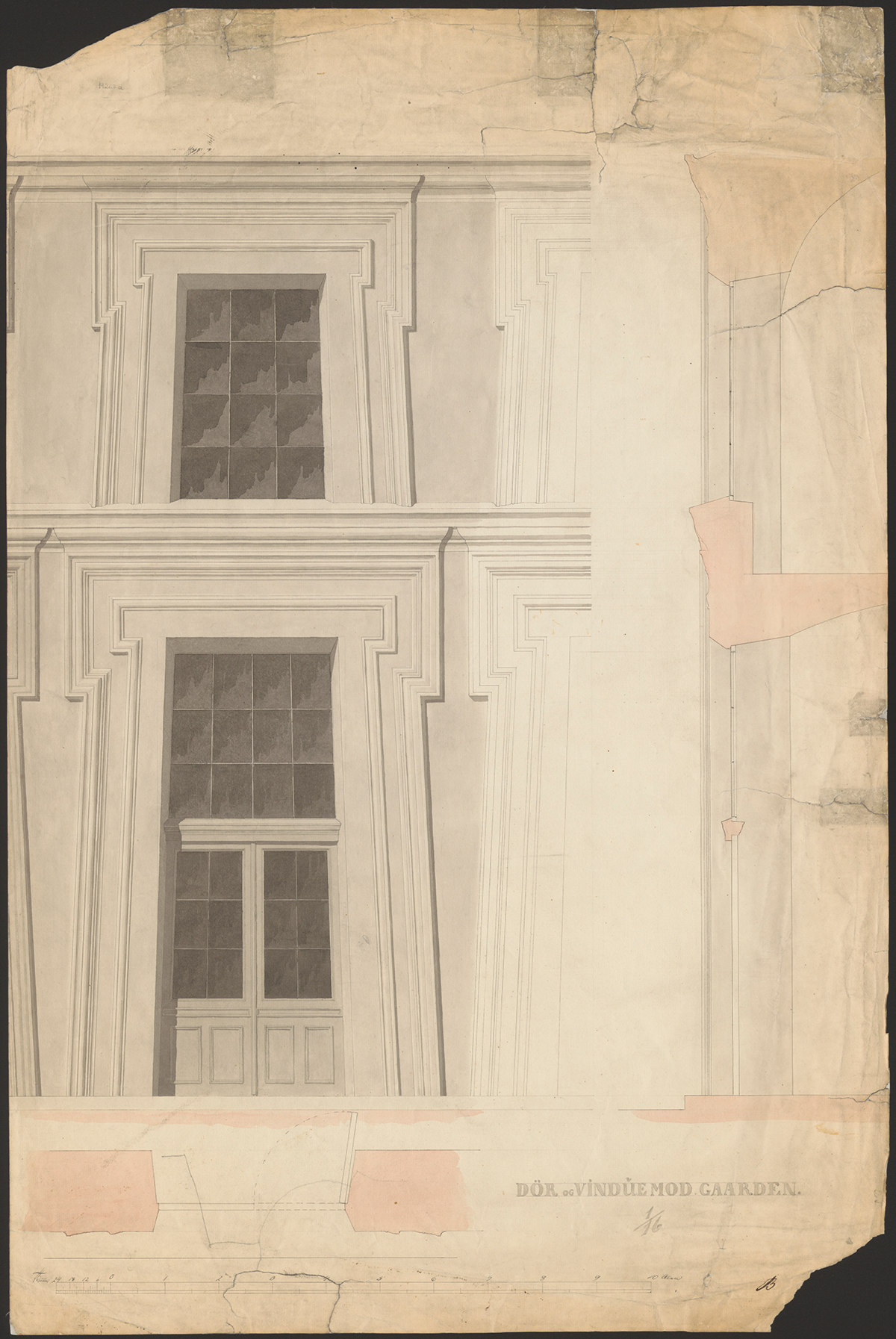

1834 portrait of Gottlieb Bindesbøll by Wilhelm Marstrand, Wikimedia Commons | an early proposal for Thorvaldsens Museum by Bindesbøll, heavily inspired by Schinkel's Altes Museum, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1842 color sketch of the west elevation, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | GF Hetsch proposal and site plan, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Hetsch proposal for building Thorvaldsens Museum on the site of the then-unfinished Frederiks Church, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | site plan for the final museum site, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | cross-section sketch, 1839, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | north elevation sketch, 1839, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | portal detail, Det Kgl. Bibliotek

Having secured their national hero and his art, the Thorvaldsen Museum backers set about building their man his museum and his tomb (Thorvaldsen was buried in the museum’s courtyard). Architect Gottlieb Bindesbøll’s proposal beat out plans by G.F. Hetsch and J.H. Koch to win the design competition. This was Bindesbøll’s first independent commission as an architect–but his uncle, Jonas Collin, was chair of the building committee and Bindesbøll was in regular contact with Thorvaldsen himself for years as he developed his proposal.

Thorvaldsens Museum was constructed during the inflection point of a couple interesting trends–the development of the modern museum and the shift from classical architecture to historicism.

Until the early 1800s, art was displayed in spaces that were overstuffed, highly decorative, and private. Museums as a European cultural phenomenon, with public access, a narrowed focus, and quieter displays, developed in the 1820s, with Berlin’s Altes Museum the forerunner for the modern museum. Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s museum heavily influenced Bindesbøll–his initial proposal looks like a copy of the Altes Museum–but the interior is where the modern leap of Thorvaldsens Museum is most apparent. Organized into small cells to encourage focused contemplation of individual pieces, lit by natural light as if it were the sculptor’s studio, Thorvaldsens Museum was a new frontier in the exhibition of sculpture.

(The light thing is pretty funny–it was an absolute key design consideration, as Bindesbøll attempted to literally recreate the lighting conditions of Thorvaldsen's studio in Rome. Gas lights were an emphatic no-go. Naturally, when it opened in 1848, the public found the interiors way too dark–Copenhagen isn’t Rome, and I imagine the museum must’ve closed at like 2:00pm in the winter.)

1850s, Heinrich Hansen, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1865, Museum of Copenhagen | 1870, Museum of Copenhagen | Thorvaldsen's grave in the courtyard, 1878, Em. Bærentzen & Co. after Christian Olavius Zeuthen, Thorvaldsens Museum via Wikimedia Commons | 1890, Museum of Copenhagen | 1899, Museum of Copenhagen | early 1900s, Fritz Theodor Benzen, Museum of Copenhagen | 1912, Fritz Theodor Benzen, Museum of Copenhagen | Courtyard from the roof looking west, Museum of Copenhagen

The other inflection point here is the transition from classicism to historicism in Danish architecture. Moving beyond the strict formalism of neoclassicism, with its almost academic imitation of Greco-Roman forms, historicism remixed elements from a wide array of periods and places to create something new that also evokes an imagined past. Thorvaldsens Museum stands right at that hinge. Bindesbøll started with a neoclassical inspiration, the Parthenon and Erechtheion, but then mashed things up with the sloping portal motif lifted out of ancient Egypt and a vivid color scheme inspired by the archeological findings at Pompeii. The interior is even better, an absolute riot of color and patterned tile. This museum launched the architect's career, and over the next few decades Gottlieb Bindesbøll would become one of Denmark’s most influential practitioners of historicism as it supplanted neoclassicism.

You could also call Thorvaldsens Museum a low-key example of adaptive reuse, more than a century before that term existed. This was the site of the Royal Carriage House, built in the 1740s and offered up by the monarchy to support the museum project. Turns out that they didn’t demolish the whole thing though–Bindesbøll’s museum reused (some of) the carriage house walls.

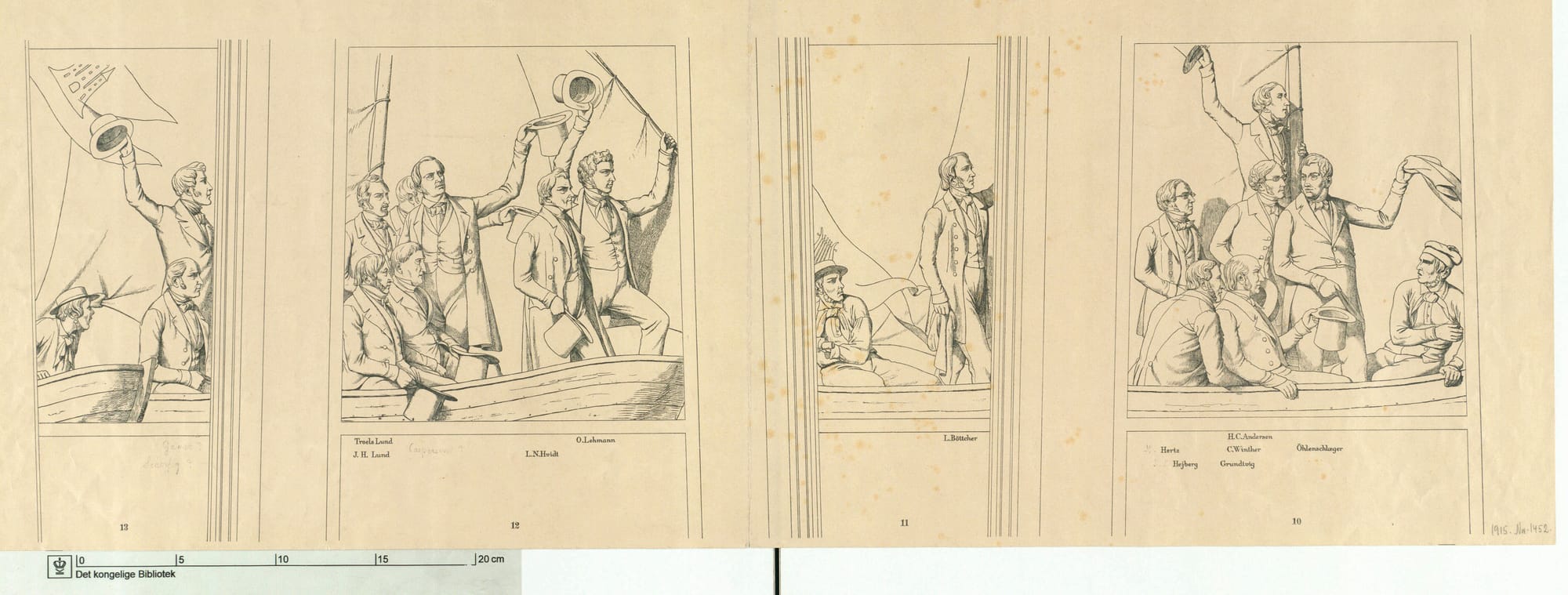

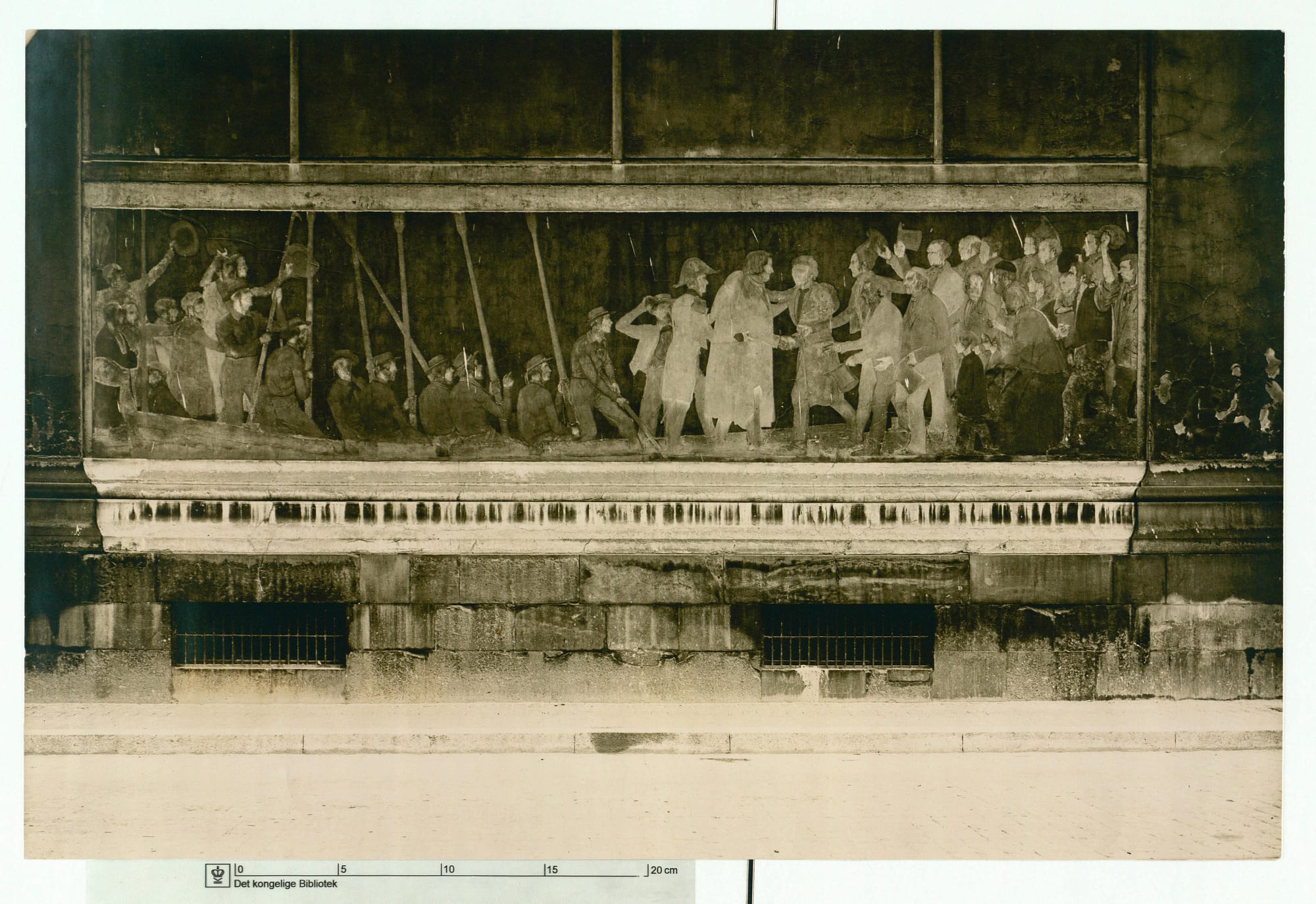

Sketch of Sonnes' frieze panel of various luminaries greeting Thorvaldsen on his arrival, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | undated photo of the frieze, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1888, the Museum of Copenhagen | the frieze with a beer wagon, undated, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1945 photo with Danish resistance members, The Museum of Danish Resistance via Wikimedia Commons | 1950s restoration of the frieze, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 2018, Leif Jørgensen, Wikimedia Commons

Maybe my favorite part of Thorvaldsens Museum are the frescoes painted on its walls. Painted by Jørgen Sonnes, they depict Thorvaldsen’s triumphant arrival in Copenhagen and the unloading of the sculptures for the museum. Famous Danes like Hans Christian Andersen and Adam Oehlenschläger make appearances, but for me the best part is the record of the everyday people who were involved in the effort–a rare appearance of normal workers in this kind of art, and right next to the royal palace no less. In rough shape after a century exposed to the elements, in the 1950s Axel Salto recreated the murals.

Today, Thorvaldsens Museum remains dedicated to the 19th century neoclassical sculptor and his personal collections. His antiquities collection is quite interesting in this context, with pieces selected for their form and style rather than historical importance or provenance–they constituted a library of inspiration for the sculptor.

That said, forecasting taste and values centuries into the future is really hard, as is keeping a single artist's body of work fresh for that long, so it’s interesting to see how the museum is working to remain relevant. They recently digitized thousands of primary source documents–mainly letters to, from, and about Thorvaldsen–and put them online, an incredible archive. To create connections between the collection and more current perspectives, they have also started organizing contemporary exhibitions in dialogue with the space, including a particularly neat Sean Scully show in 2022.

As an interesting attempt to turn a celebrity artist into a national icon, a delightfully quirky bit of architecture, and a fine museum, in my opinion Thorvaldsens Museum is grandfathered in...but in general I think it's not great to let a bunch of rich corpses dictate public culture from the grave. Thorvaldsens Museum has existed for 175 years and presumably will for 175 more; that is a long-ass time. When the rich and powerful want public land or public support for their pet projects–utterly certain that their collection, their favorite artist, or their weird little hobby will remain relevant forever–we can say no.

Production Files

Further reading:

- The conservation listing

- The triumph of art at Thorvaldsens Museum : 'Løve' in Copenhagen by John G.W. Henderson

- 'Thorvaldsen's museum: A display of life and art, 1848–1984' by Lisbet Balslev Jørgensen in International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship

- Buildings for Bodies of Work: The Artist Museum After the Death and Return of the Author by Maarten Liefooghe in Architectural Histories

- Thorvaldsens Museum: Kunstens første tempel

- At the Danish Design Review, Arkitekturbilleder.dk, and Copenhagen Architecture

- The incredible primary source archive created by Thorvaldsens Museum itself

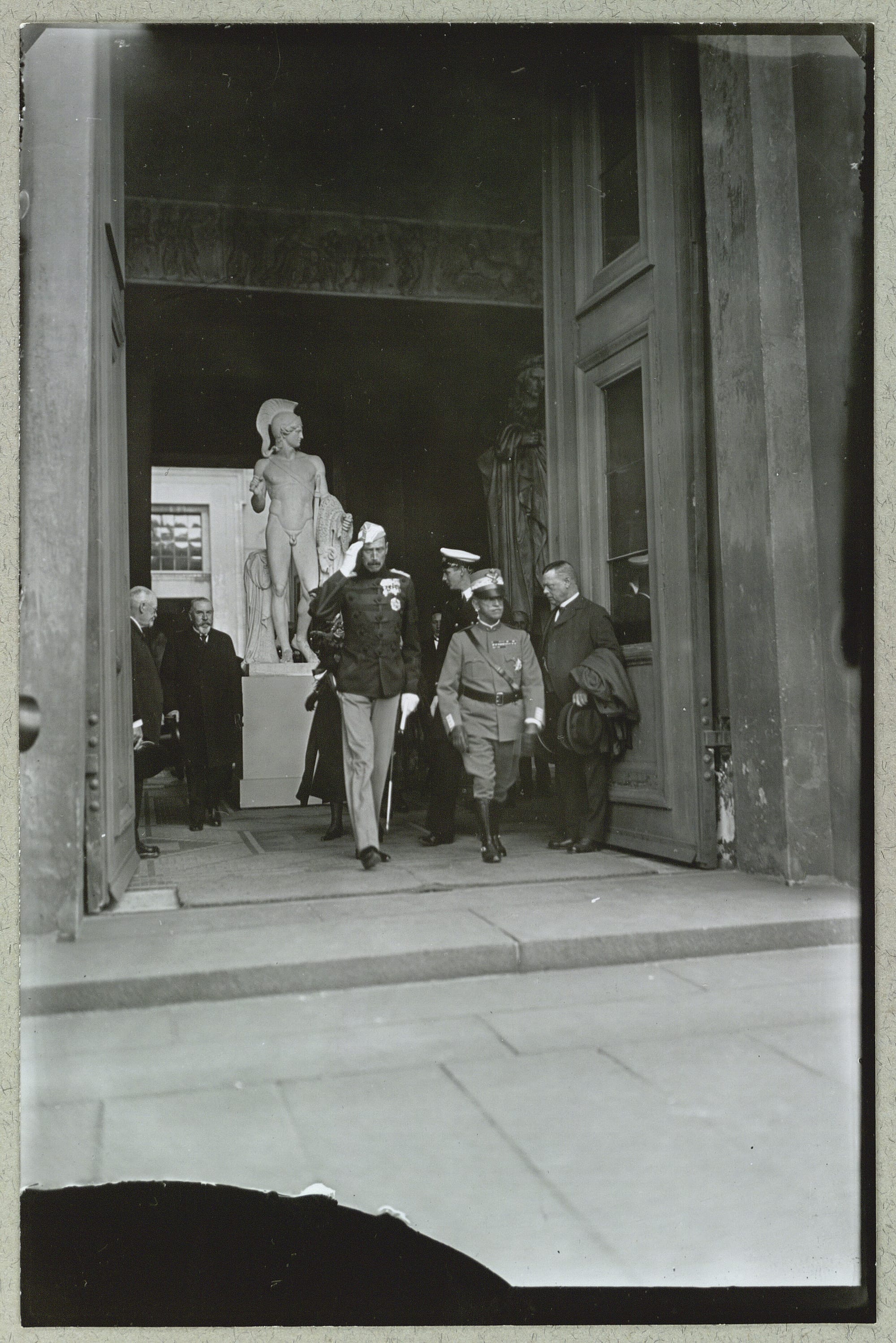

Thorvaldsens Museum had a cameo in all sorts of history–here, visits by various heads of state and prepping for World War II.

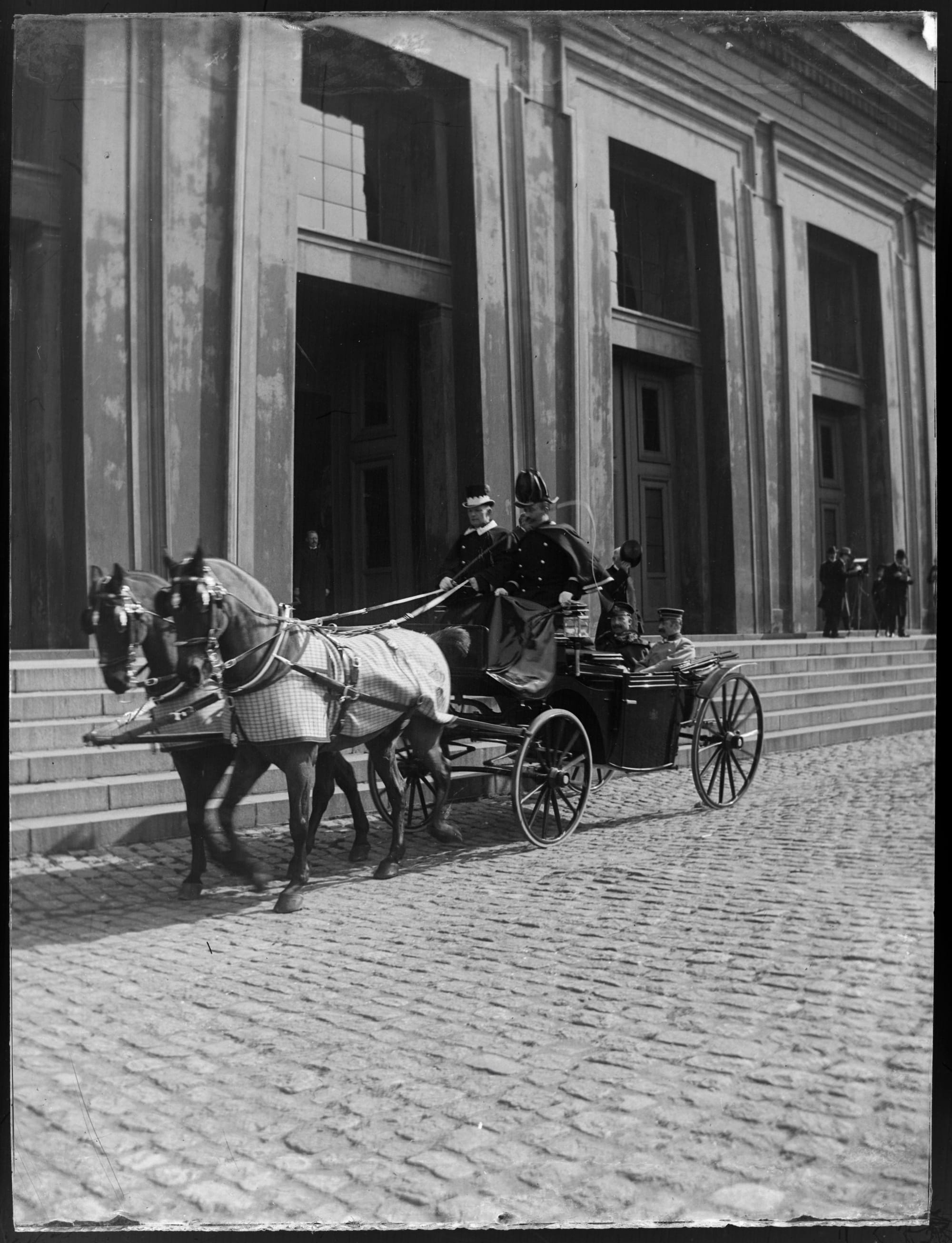

Kaiser Wilhelm II in a carriage in front of the museum in 1902, Lars Peter Elfelt, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Italian King Victor Emmanuel III and King Christian X of Denmark in 1922, Holger Damgaard, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | King Albert I of Belgium and King Christian of Denmark in 1928, Holger Damgaard, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Soldiers sandbagging the building in 1939 as war breaks out in Europe; photo 1, photo 2, photo with frieze, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | barricade in 1945 after liberation, Det Kgl. Bibliotek

In 1884 Christiansborg Palace burned down, putting Thorvaldsens Museum in danger. The Museum of Copenhagen.

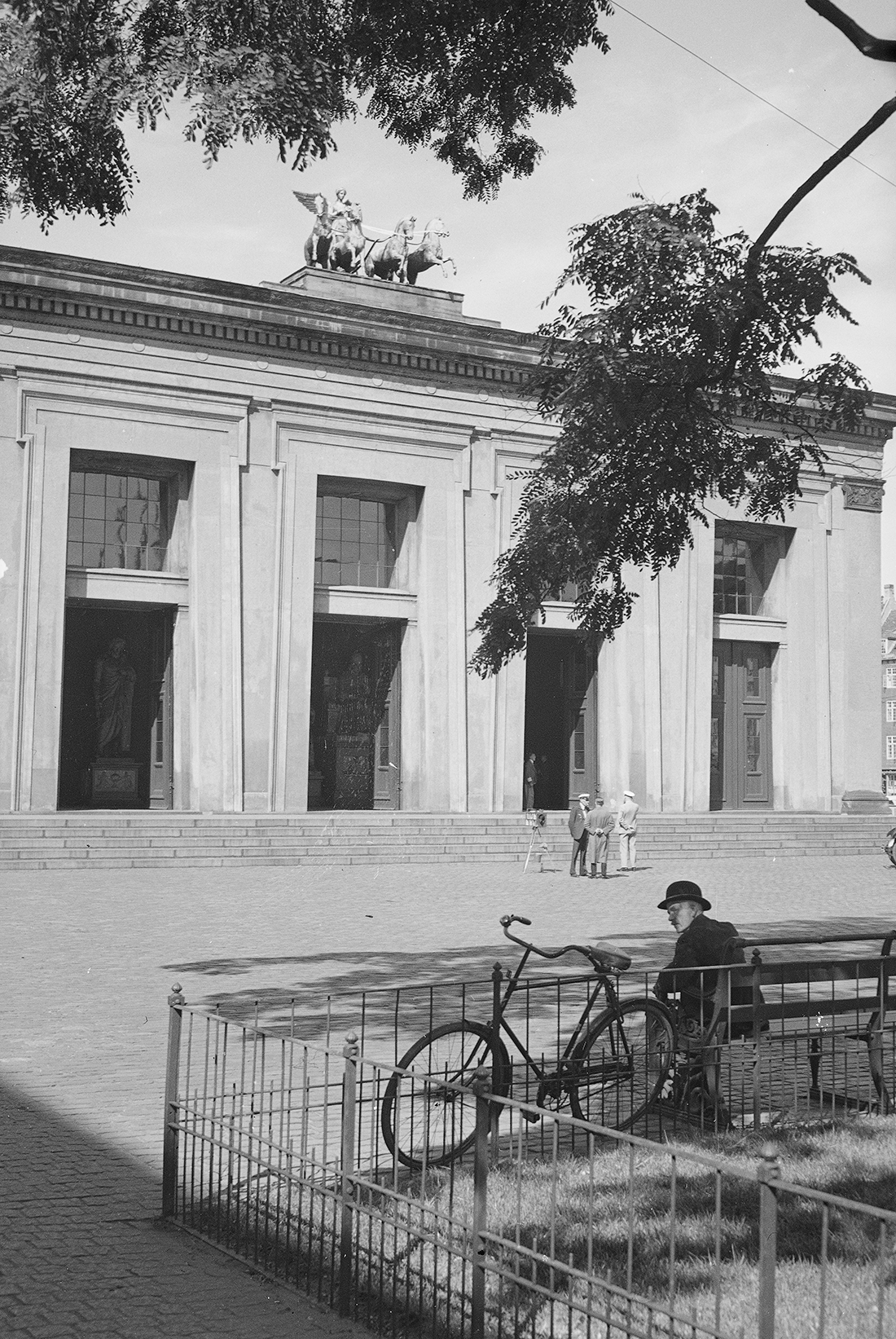

The bronze sculpture of Victory above the entrance was sculpted by H.W. Bissen, according to Thorvaldsens plans.

Victory from the roof looking north, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Victory looking west, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Victory in the 1880s, Frederik Riise, the Museum of Copenhagen

Illustration from the 100th anniversary of Thorvaldsens birth, 1880, Bernhard Olsen, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1880, Fr. Markvardt, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1880, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1900, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1903 in the snow, Peter Elfelt, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Men with rowboat, undated, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Man with bike, Jonals Co., Det Kgl. Bibliotek

Member discussion: