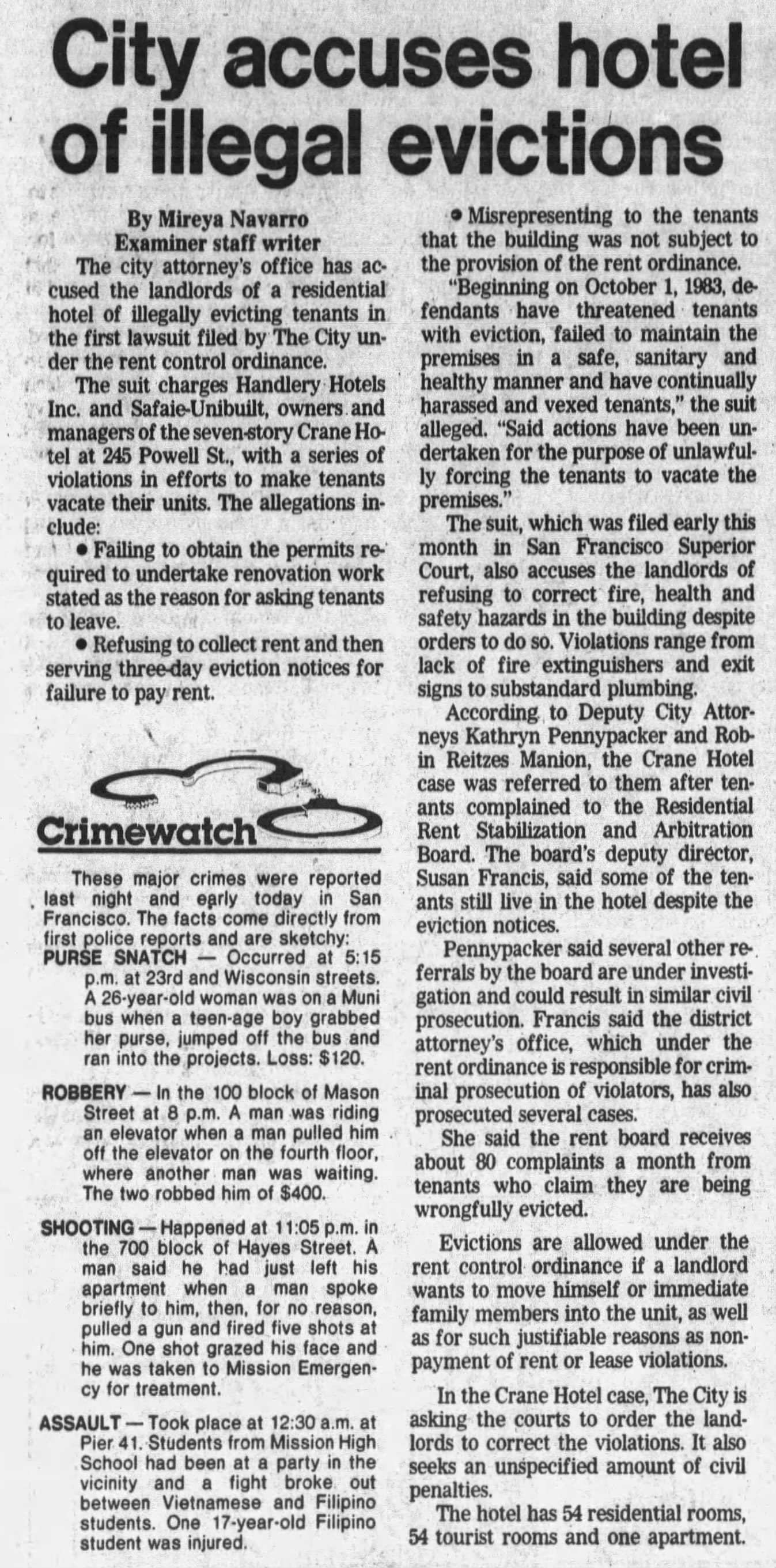

The former Hotel Crane, one block from Union Square and built in 1910 as a residential hotel, exemplifies a key aspect of San Francisco’s housing shortage and homelessness crisis: the disappearance of flexible and cheap single room occupancy (SRO) units. The loss of the 100+ units here is especially sickening, though. They were taken off the market after a 1981 ordinance outlawed the demolition or conversion of SROs and after the city sued the building owner for illegally evicting tenants.

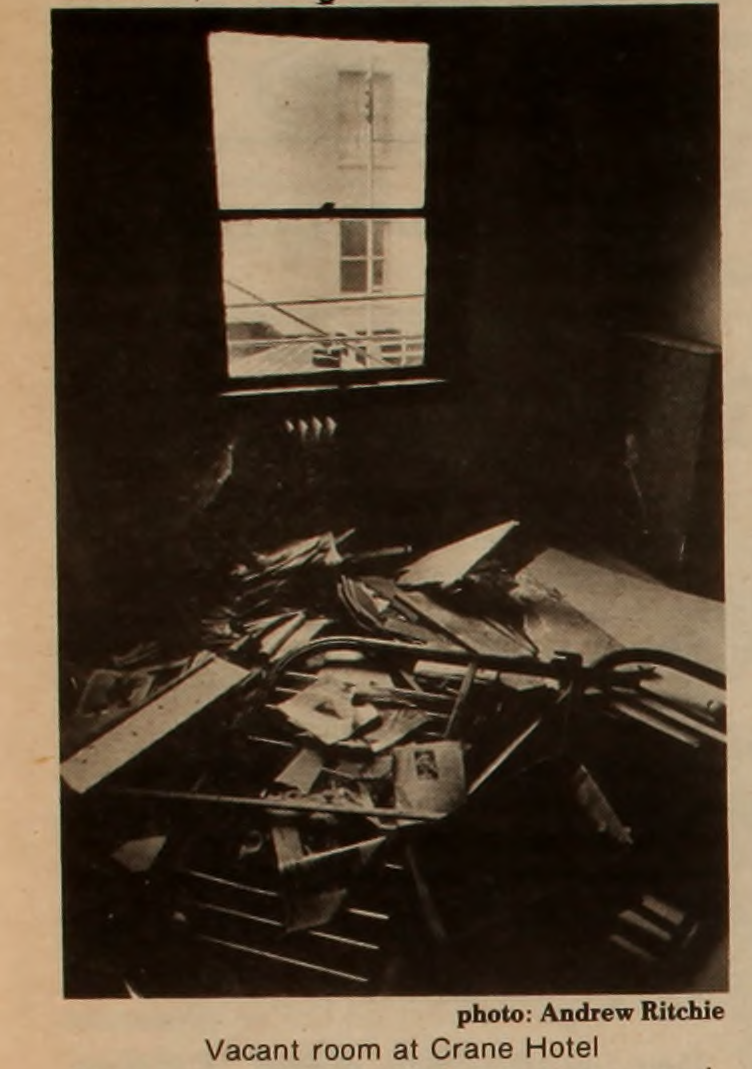

In 1984, the City of San Francisco accused Handlery Hotels (a major local hotel company) and their contracted SRO operator of intentionally letting conditions in the Crane deteriorate in an illegal attempt to force out the remaining tenants by making their home a squalid hellhole. The Tenderloin Times wrote that “the conditions in this 112-room hotel are almost beyond belief”. After settling the suit with the city and paying off the tenant holdouts, Handlery successfully emptied the building. The hotel company took their newly vacated SRO and did…nothing.

…yup, this building has sat vacant for more than 35 years, part of the 15,000 units of SRO housing that San Francisco lost between 1970 and 2000.

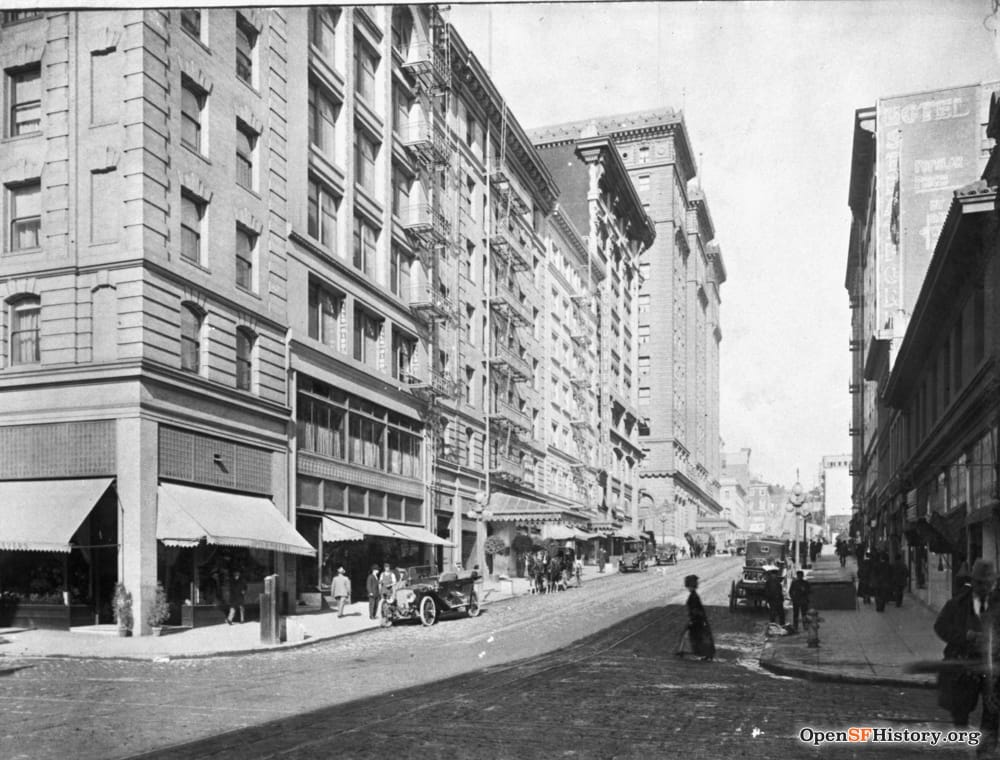

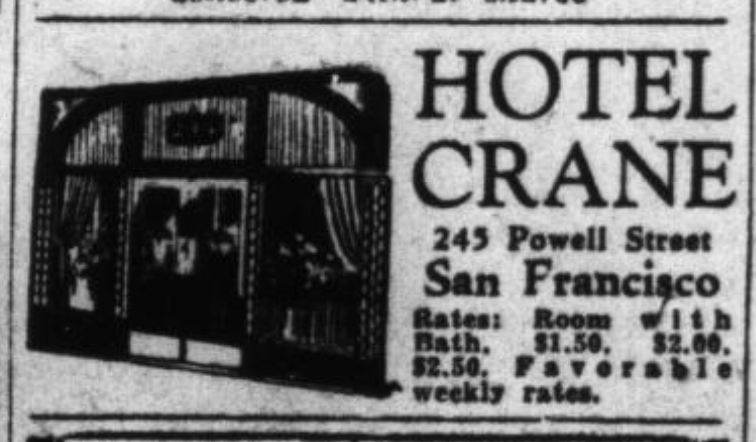

Usually here I’d ask “so, what’s changed?”, but this postcard has the building cosplaying as Art Deco for some reason–it’s a quirky one. The storefronts have changed with the retail tenants over the years, but the windows and cornice are all the same. They also airbrushed out the fire escape, which was definitely there in 1941 when this postcard was published.

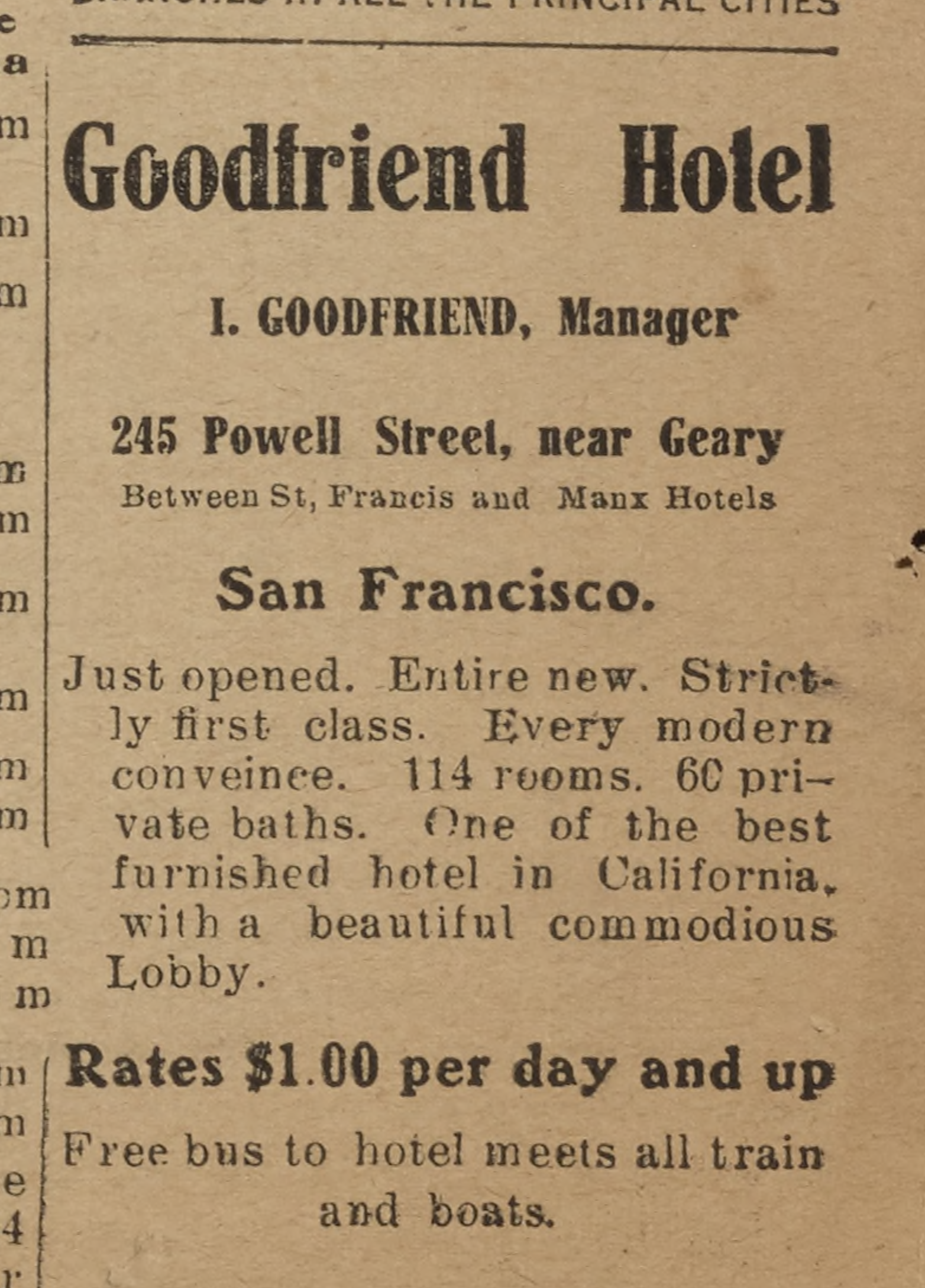

Building permit for a five-story building in 1909 | Building permit to add two more stories to the under-construction hotel in 1909 | "Hotel being built taken on lease", article on Goodfriend leasing the under-construction hotel in 1909 | Hotel Goodfriend lobby postcard, undated | Powell Street with Hotel Goodfriend visible on the left, 1909-1910, OpenSFHistory / wnp33.03241 | 1953 in color, OpenSFHistory / wnp12.00319 | 1955, SCRAP Negative Collection, OpenSFHistory / wnp100.00080

Designed by architect Mateo Mattanovich, initial plans called for a five story building here, but Ignaz Goodfriend leased the hotel while it was under construction–they kept on going, adding two more floors. A typical example of the utilitarian Renaissance Revival blocks that popped up across San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake, the Hotel Goodfriend opened in 1910 as a residential hotel. Over the next 75 years the building hosted a flexible mix of tourists and permanent residents, operating as the Goodfriend, the Antlers Hotel, the Henry George Hotel (!), the Hotel Fox, and the Hotel Crane.

Its 110+ units formed part of a San Francisco SRO stock that was once 90,000 deep. SROs aren’t perfect, but they’re a cheap, flexible, and independent form of housing that doesn’t require a credit score or a security deposit–they can be a lifesaver for people with housing insecurity.

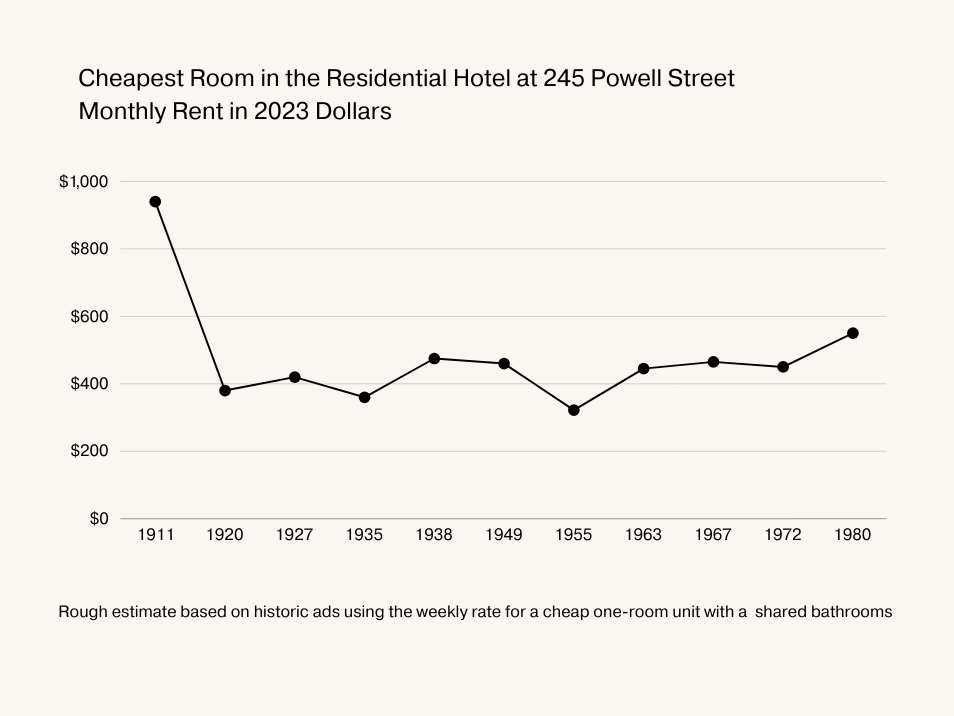

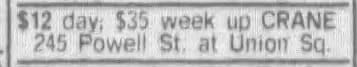

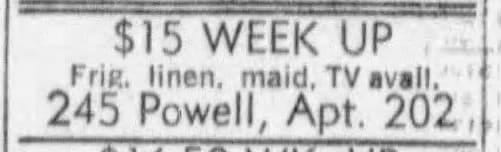

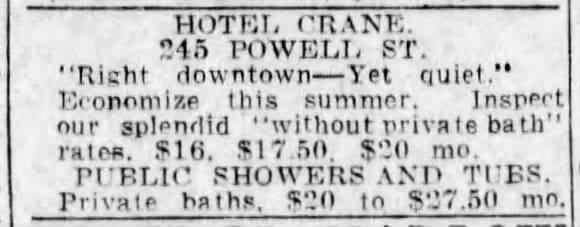

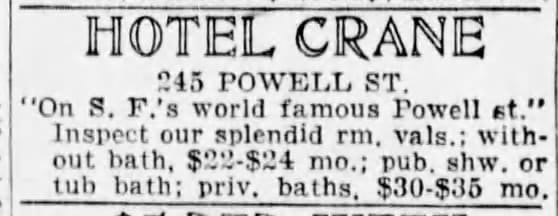

As you can see, the building maintained its affordability into the 1980s, when Handlery emptied it out. In 1920, that affordability meant that the hotel staff could afford to live here: operating as the Hotel Antlers, this residential hotel paid its “linen room woman” $3 a day for a six day work week. If she wanted, a permanent room with a shared bathroom would’ve been affordable to that linen room lady, with the rent making up ~30% of her income. That affordability and flexibility that disappeared when Handlery forced out the tenants and took the building out of the housing market entirely.

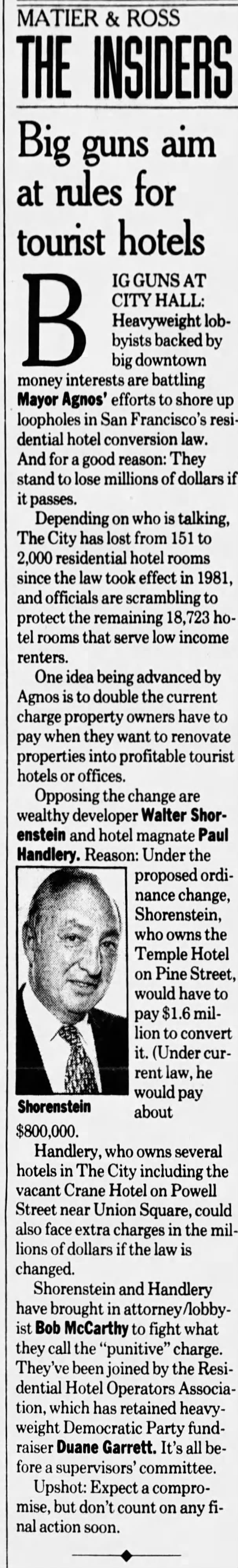

Housing activists fought hard to protect San Francisco’s remaining SROs as they disappeared in the 1970s, and in 1981 the city passed a Residential Hotel Conversion and Demolition Ordinance that prohibited the demolition of SROs or their conversion into tourist hotels. Clearly, one loophole was the conversion of an SRO into nothing at all, but the ordinance, coupled with tenacious activist attention that continues to this day, has mostly stemmed the bleeding—San Francisco has a stable-ish stock of roughly 19,000 SRO units today.

Photos from "Hotel Shuffle: Tenants Out, Tourists In" by Rob Waters in the Tenderloin Times in 1984 | 1984 article on the city lawsuit charging Handlery Hotels with illegally evicting tenants

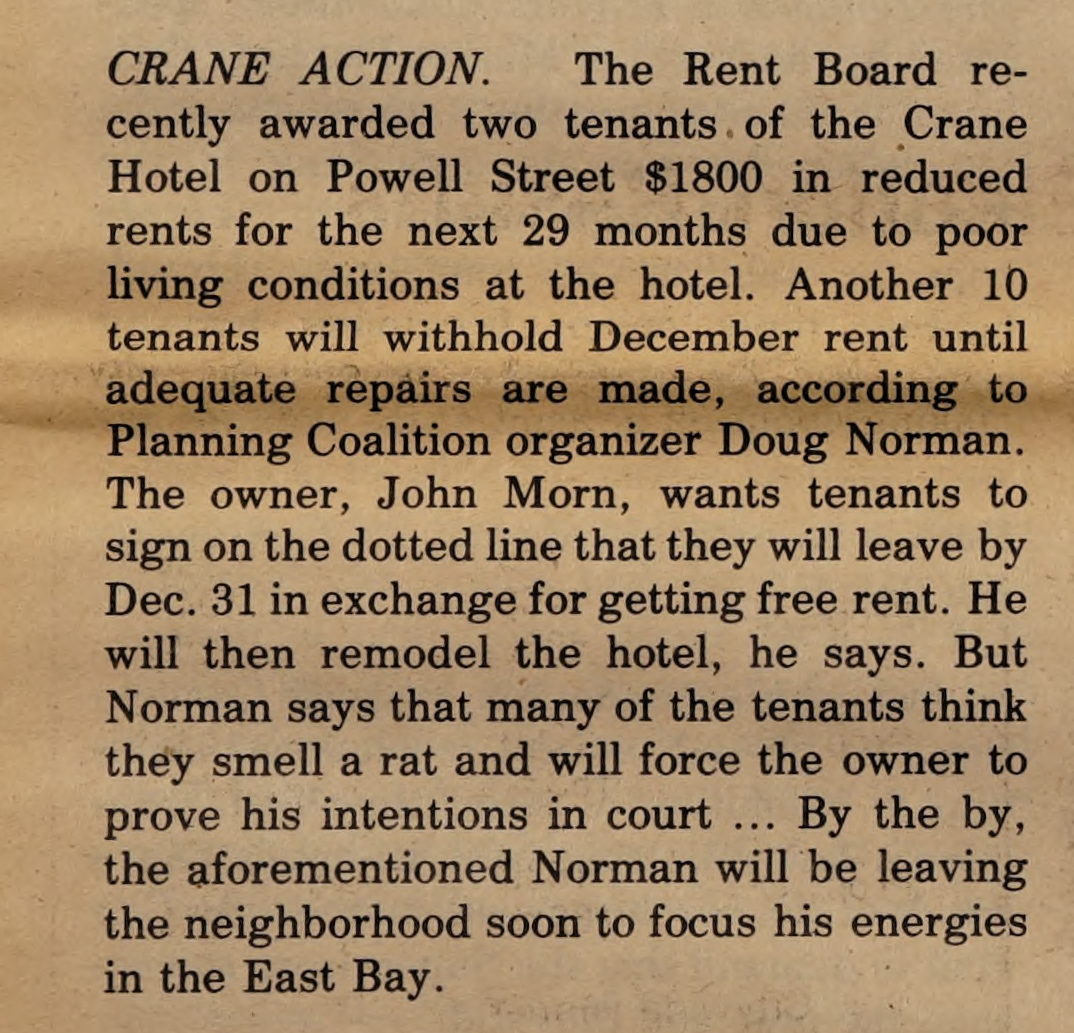

Property owners hated the anti-conversion ordinance, and in the early 1980s the Crane’s owners let the building deteriorate in an attempt at eviction-by-neglect. A 1984 visit from the Tenderloin Times found “hallways strewn with litter, bathrooms with no lights, dangling electric wires and toilets stained with feces, and scores of doorless, vacant rooms overflowing with garbage of all kinds”, but the SRO operator promised that once the remaining tenants left they would “remodel the whole building from top to bottom”. 40 years later, it’s clear that was a total fucking lie.

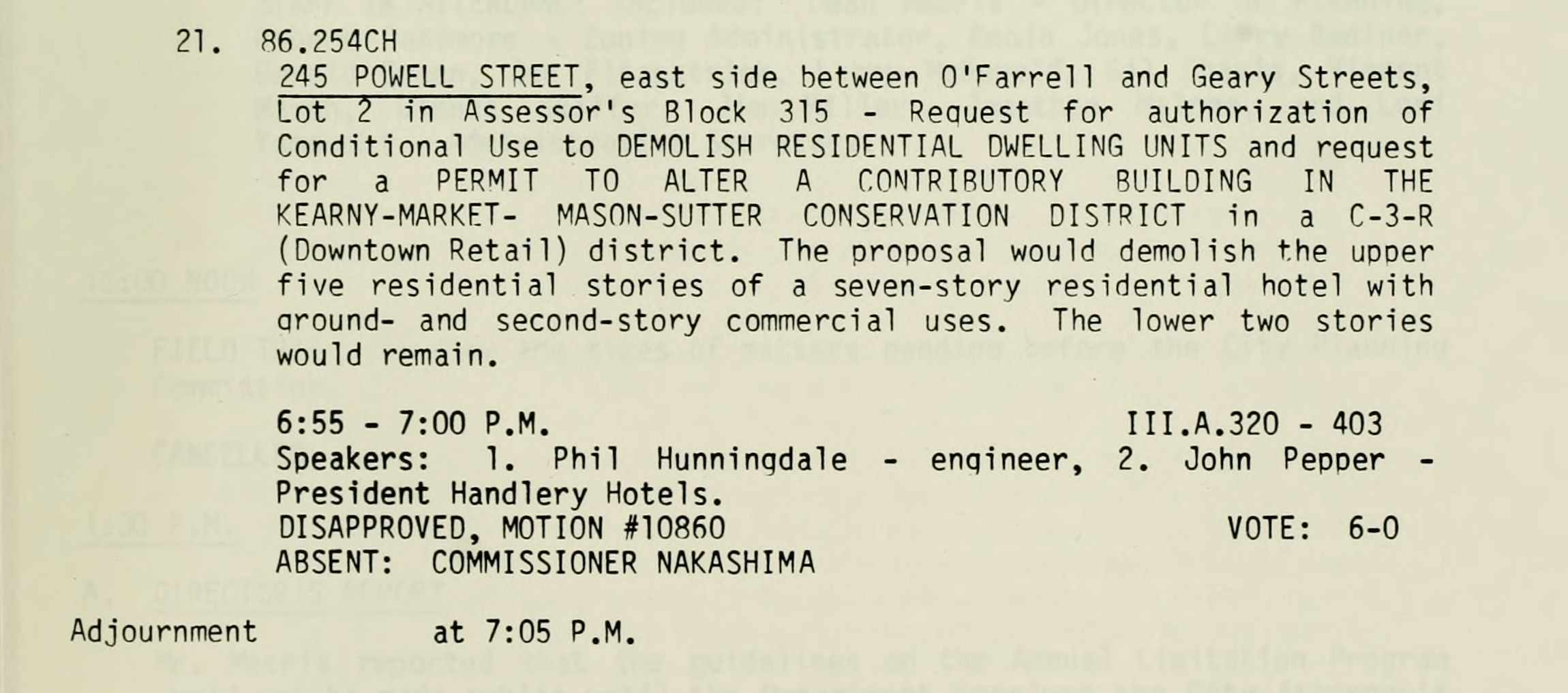

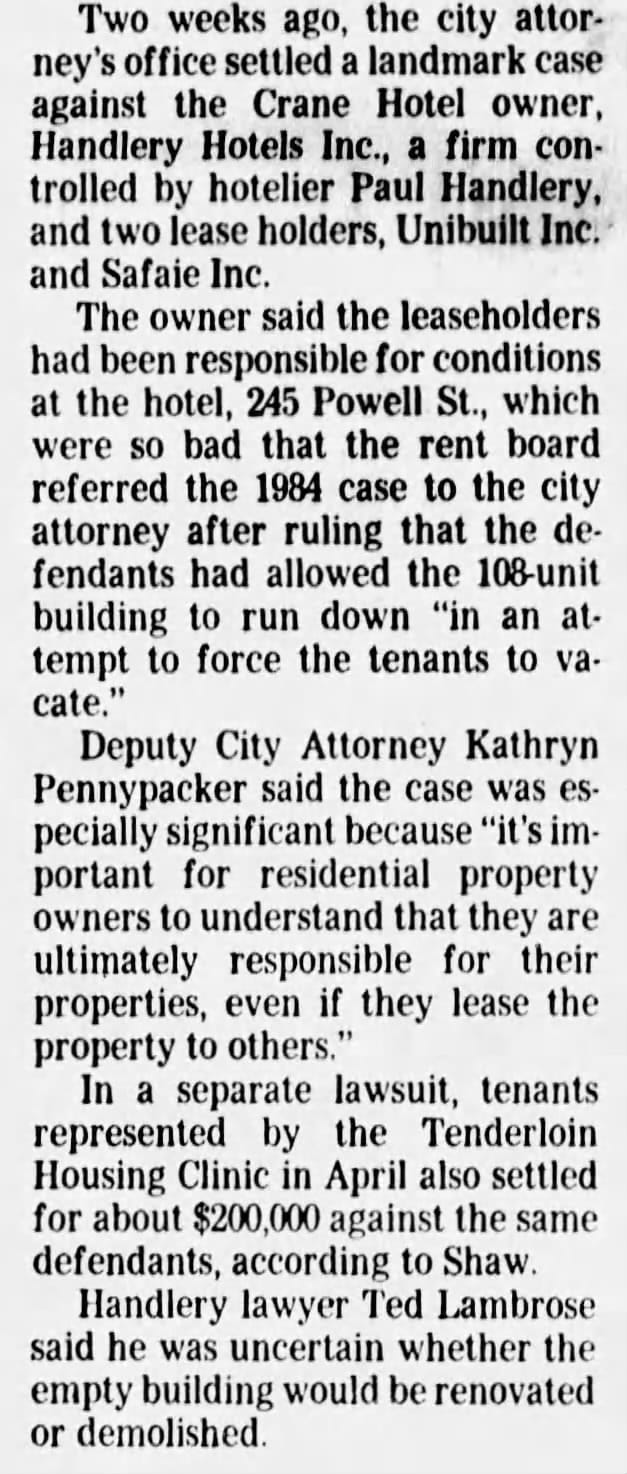

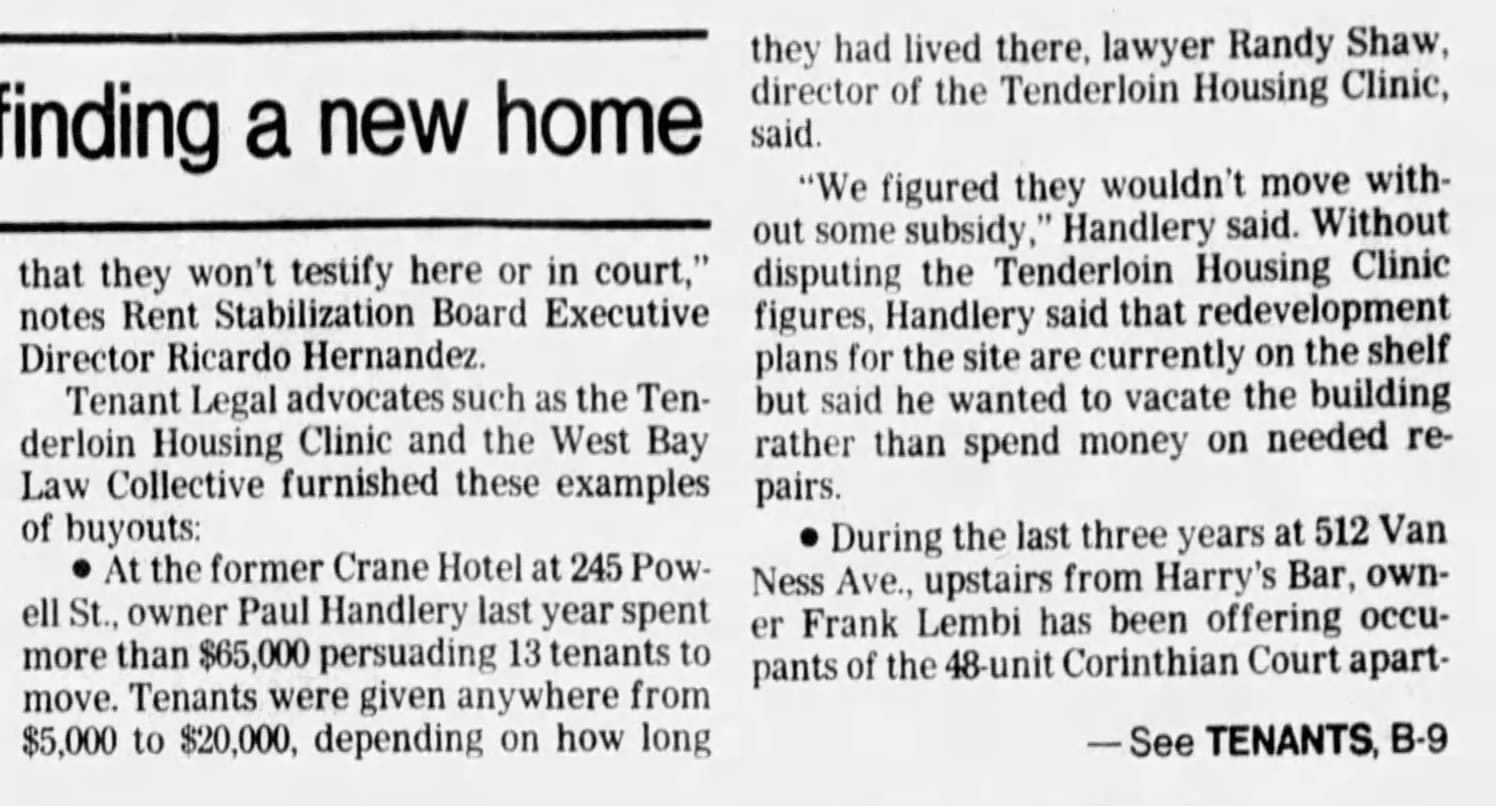

In 1984 the city sued Handlery, the SRO operator, and the leaseholder (Unibuilt & Safaie) for illegal eviction, together with a concurrent lawsuit from the remaining tenants themselves, who were represented by the Tenderloin Housing Clinic. They settled the suit with the city for $250k in 1986, and paid $65k to the last 13 tenants to get them to move. Almost immediately after emptying out the building, Handlery Hotels applied to demolish the hotel floors, leaving only the first two floors for commercial uses. That seems to me like a shameless attempt to circumvent the SRO demolition ordinance, but it never came to that. 245 Powell Street is also a contributing structure to the Kearny-Market-Mason-Sutter Conservation District, so the San Francisco Planning Commission had to sign off on Handlery’s demolition plans. The commissioners voted 6-0 to reject their request to demolish the upper five floors.

That demolition denial ultimately feels like a hollow victory–Handlery’s capital strike has basically worked. It took a serious effort to empty the Crane, but 35 years later those upper floors are still vacant in a city desperately short of housing, and it’s almost impossible to foresee a future where anyone calls 245 Powell home.

1959, Roger W. on Flickr

Production Files

Further reading

- Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States by Paul Groth

- City for Sale: The Transformation of San Francisco by Chester Hartman

- This history of SROs in San Francisco from the Central City SRO Collaborative

- "Heartbreak Hotel", a compassionate and insightful look at SRO life in San Francisco in the 1990s from SF Weekly

- From Urban Renewal and Displacement to Economic Inclusion: San Francisco Affordable Housing Policy 1978-2014 by Marcia Rosen and Wendy Sullivan

- San Francisco’s Single-Room Occupancy (SRO) Hotels: A Strategic Assessment of Residents and Their Human Service Needs by Aimée Fribourg (pdf)

- Building for Downtown Living: The Residential Architecture of San Francisco's Tenderloin by Eric Sandweiss

- "Hotel Shuffle: Tenants Out, Tourists In" by Rob Waters in the Tenderloin Times in 1984

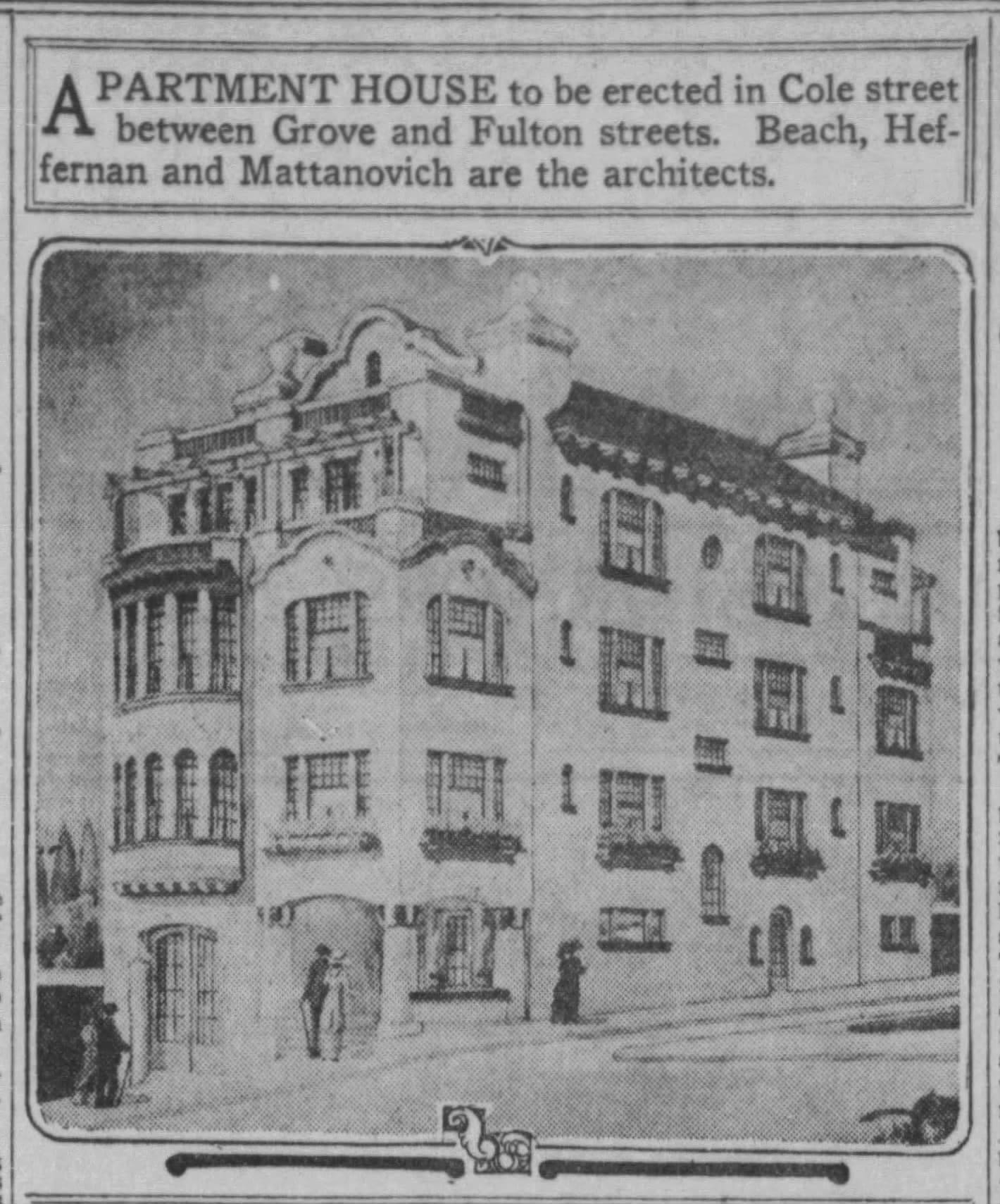

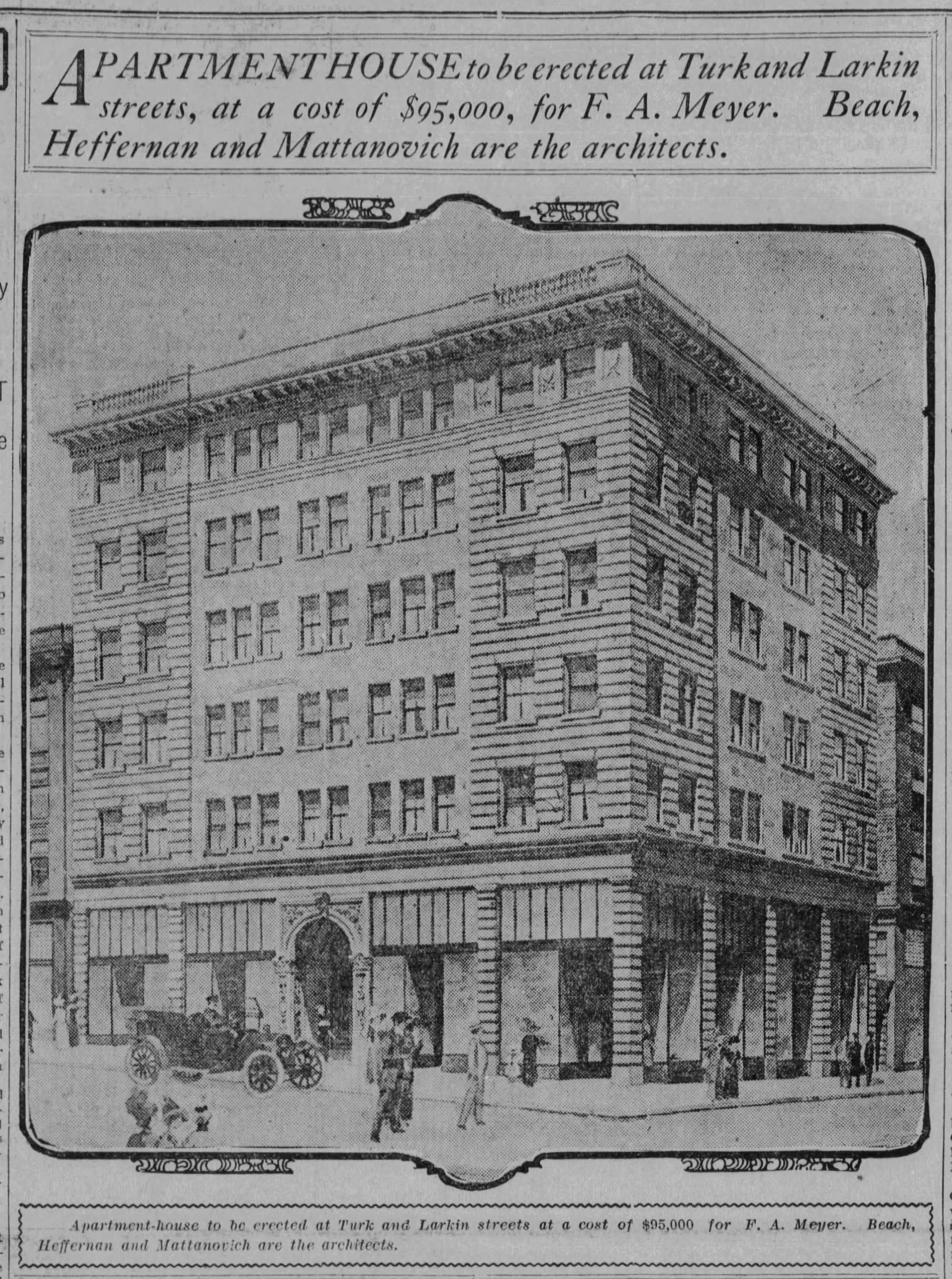

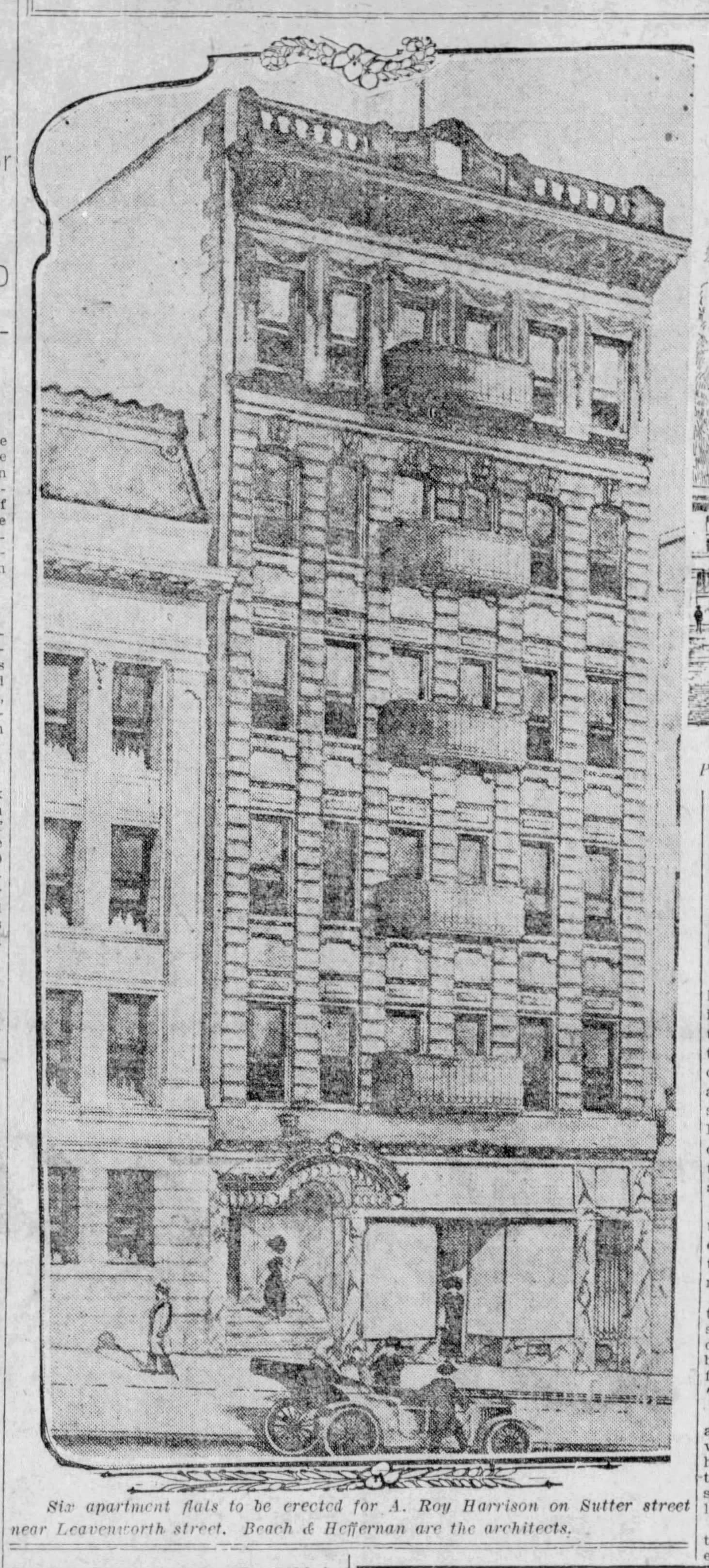

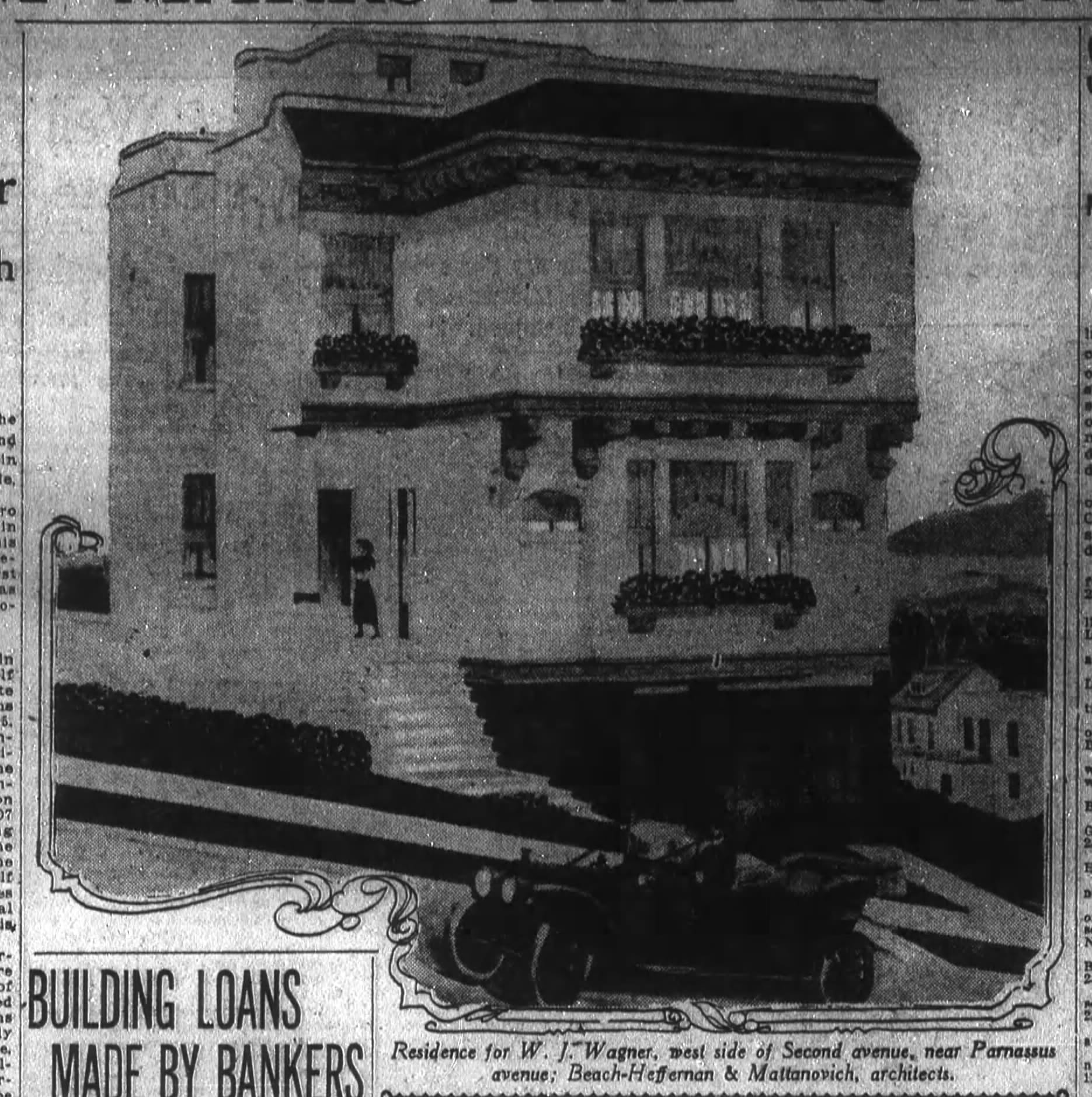

The architect of the Crane, Mateo Mattanovich, was a pretty obscure San Francisco architect. Born in Zadar in present-day Croatia when it was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Mateo (whose name was spelled in a million different ways depending on the source) arrive in San Francisco at the perfect time for a builder: sometime between 1905 and 1910. Independently and as part of the firm Beach, Heffernan, & Mattanovich, in the 1910s he designed quite a few apartment buildings and a couple residential hotels, usually in reinforced concrete. Here are some of them:

First two: Mattanovich-designed apartments at 43 Cole Street | Second two: the Mattanovich-designed Larkin-Turk Apartments | Third two: Mattanovich-designed apartments at 866 Sutter Street | A demolished Mattanovich-designed residence | A Mattanovich single family home, status unknown | A Mattanovich-designed residential hotel at 344 Jones Street

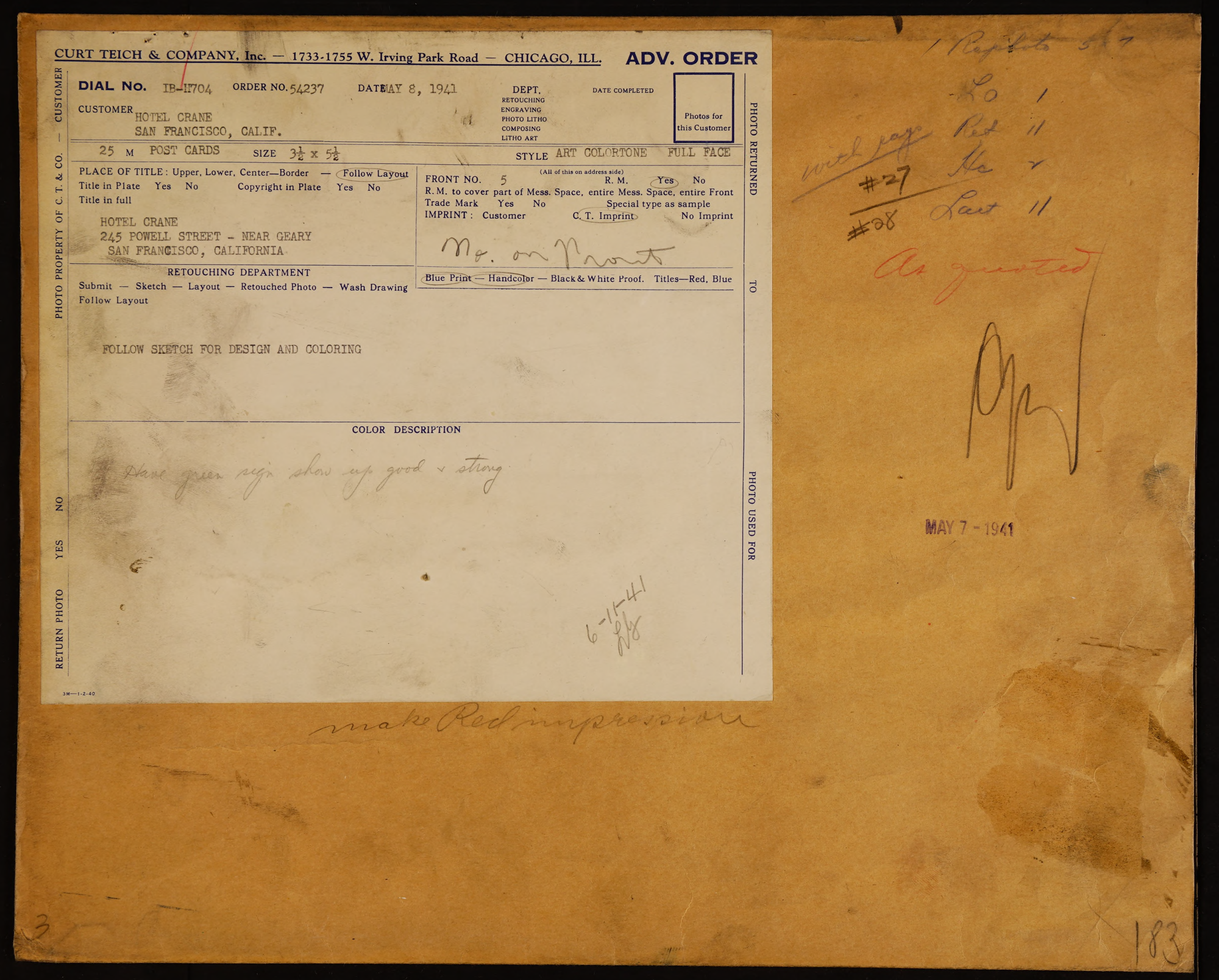

The back of the postcard and the postcard production envelope, which requests that the green sign "shows up good and strong", the Curt Teich Postcard Archive, the Newberry Library

1980s articles about the neglect of the building, the lawsuit and settlement on the illegal evictions, etc.

Ads for rooms in the residential hotel at 245 Powell Street over the years

Cars have been terrible for our cities for more than a century.

Member discussion: